My wife read the Little House books out loud to our kids, most of them more than once. The four of us once spent a day in Mansfield at the Laura Ingalls Wilder Home. Beforehand, my wife and kids were so excited you would have thought we were going to Disney World to spend the whole time on rides sitting next to Mickey Mouse. The item they absolutely had to see—the item every visitor absolutely has to see—was Pa’s fiddle.

Pa, of course, was Charles Ingalls, father of Laura Ingalls Wilder. It’s clear from the books that Laura idolized him. He is almost infallibly kind, wise, and strong as he led the family from Wisconsin to Missouri to Kansas to Minnesota to South Dakota. The early years of Laura’s life were marked by almost constant upheaval. Through sickness and drought and locusts and unbearably cold winters, there was one constant: Pa’s fiddle. It appears in every book, as Pa played it at parties for entertainment and at night to pass the time, and on Sundays as an act of worship. But even the fiddle’s prominence in the books and the TV show based on the books doesn’t fully explain the power that relic has over people who see it. Pamela Smith Hill, author of Laura Ingalls Wilder: A Writer’s Life and editor of Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Pioneer Girl: The Annotated Autobiography, summed up that allure in an essay at LittleHouseOnThePrairie.com. “Pa’s fiddle is a kind of time machine. You don’t have to hold it in your hands, as I did, to sense its simple beauty, grace, and magic. Simply seeing it for yourself can transport you back in time.”

And Pa’s fiddle is not the only time machine on display in Missouri. Across the state, there are relics—some of them instantly recognizable, some of them obscure, some of them daily items, some of their tools of superstars—that take visitors hurtling across the decades.

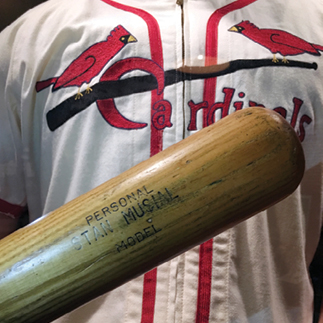

Stan Musial’s Bat • St. Louis

Stan Musial played 22 seasons for the St. Louis Cardinals and was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1969. Even decades after he retired, when Musial visited Busch Stadium, a buzz went through the crowd and followed him wherever he went as if the Pope had shown up for Sunday Mass. People who knew him spoke of him in revered tones, not just as a player but as a man.

That in part explains why so many fans pick up Stan Man’s bat and swing it when they walk through the Cardinals Hall of Fame. (This is the rare relic that is not stored behind glass for safekeeping.)

But it’s not just Musial’s bat that is popular here. So are the bats of various other players that have been displayed over the years. Almost everybody has hit a ball with a bat at some point in life—or shot a ball through a hoop, or used some device in pursuit of excellence, whether it’s sports or music or some other activity. And we have all imagined those devices would make us heroes. Even if we never succeeded outside of our dreams, we can still, in some small way, feel a connection to our champions, whoever they are, whatever they did, through that bat.

700 Clark Avenue • 314-345-9600 • Cardinals.com/museum

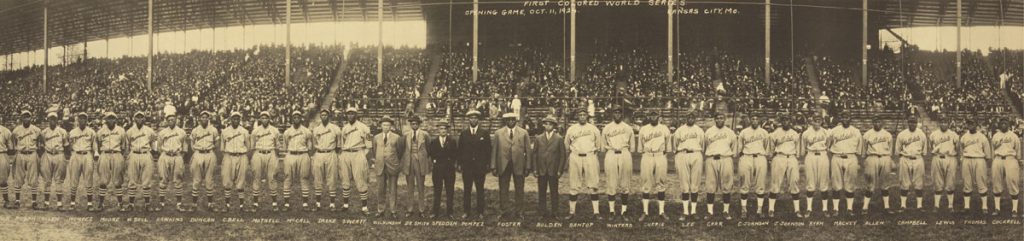

Relics of the Negro League • Kansas City

It’s relatively easy for the Cardinals Hall of Fame to find used game items. But that’s not true for the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City. Items from Negro Leagues games are not nearly as common as their counterparts from Major League Baseball. It was decades before American sports culture recognized the importance of the Negro Leagues, and by that time, most items had been discarded or destroyed. “There’s not a ton of it,” says Ray Doswell, vice president and curator of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City. “That’s part of the story.”

That makes the limited number of relics amassed by the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum even more important. Two of the museum’s most notable items are Kansas City Monarchs uniforms—one worn by Newt Allen and another by Carroll “Dink” Mothell.

Allen played nearly his entire 23-year career for the Monarchs. Some experts believe he deserves to be elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame. “Considered the best second baseman during the 1920s and early 1930s, the wide-ranging, slick-fielding middle infielder had quick hands and was superb on the pivot in turning a double play,” according to his bio at the museum’s website.

Like Allen, Mothell spent much of his career with the Monarchs. “Mother proved valuable because he could play nearly every position on the field and play it well. He had good range and speed when he patrolled the outfield, and he could go deep in the hole at short to throw runners out,” according to the assessment of Satchel Paige and Company, Essays on the Kansas City Monarchs, Their Greatest Star and the Negro Leagues, a compilation edited by Leslie A. Leaphy.

The uniforms on display at the museum are 70 to 80 years old and relatively intact. They are made of wool, as they all were in those days. To wear one was to be simultaneously hot and itchy. To play nine innings while wearing one in the Kansas City heat was to be drenched in sweat.

In addition to those uniforms, the museum offers multimedia displays and hundreds of photographs and other artifacts dating from the late 1800s to the 1960s.

1616 East 18th Street • 816-221-1920 • NLBM.com

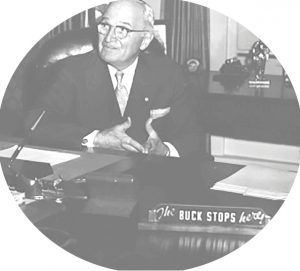

Truman’s “The Buck Stops Here” Sign • Independence

Harry Truman was born in Lamar and spent most of his childhood in Independence, which is home to the Harry S. Truman Presidential Library and Museum. The museum traces his rise from county judge to vice president to the leader of the free world. The facility houses many notable items, including his buggy, his car, and a replica of the Oval Office.

But nothing says Truman like “the buck stops here,” the saying he made famous during his eight years as president. It was printed on a sign that occasionally sat on his desk in the White House. According to a history of the sign at TrumanLibrary.org, the saying “derives from the slang expression ‘pass the buck,’ which means passing the responsibility on to someone else. The latter expression is said to have originated with the game of poker, in which a marker or counter—frequently in frontier days a knife with a buckhorn handle—was used to indicate the person whose turn it was to deal. If the player did not wish to deal, he could pass the responsibility by passing the ‘buck,’ as the marker came to be called, to the next player.”

The sign is 2½ inches tall and 13 inches wide and sits in a walnut base. It was made at the Federal Reformatory at El Reno, Oklahoma, and sent to Truman on October 2, 1945.

“The President—whoever he is—has to decide,” Truman said in his January 1953 farewell address. “He can’t pass the buck to anybody. No one else can do the decisions for him. That’s his job.” There’s a message on the other side of the sign, too. It says, “I’m from Missouri.”

500 West US Highway 24 • 800-833-1225 or 816-268-8200• TrumanLibrary.org

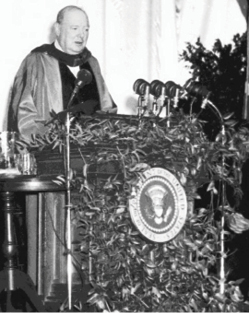

The Lectern Churchill Delivered His Iron Curtain Speech Behind • Fulton

Let’s be honest: It’s just a lectern. It’s made of wood. If you saw it in a college classroom or at the next conference you go to, you wouldn’t think anything of it. There’s really nothing special about this lectern … except for the fact that Winston Churchill stood behind it as he made one of the most important speeches of the 20th century.

On March 5, 1946, Churchill visited Westminster College in Fulton and delivered a speech that changed history. Churchill called his text, “Sinews of Peace,” but history knows it as the “Iron Curtain Speech,” a phrase indelibly linked to the Soviet empire from that day forward.

“From Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic, an iron curtain has descended across the Continent,” Churchill said. “Behind that line lie all the capitals of the ancient states of Central and Eastern Europe. Warsaw, Berlin, Prague, Vienna, Budapest, Belgrade, Bucharest, and Sofia, all these famous cities and the populations around them lie in what I must call the Soviet sphere, and all are subject in one form or another, not only to Soviet influence but to a very high and, in many cases, increasing measure of control from Moscow.”

Timothy Riley, the museum director, and chief curator says visitors view the lectern with a reverence like that afforded to Pa’s fiddle. He called such items “eyewitnesses to history.” They connect us to the past in ways pictures, books, and replicas can’t. For example, Churchill was the subject of an Oscar-winning movie last year called Darkest Hour. Watching the movie allows the viewer to learn what Churchill did and what he was like. And that’s valuable. But there’s also a distance between the viewer and Churchill.

The lectern bridges that gap. It was there when history happened. Churchill touched it, gripped it, and set his prose upon it. “It has his fingerprints on it,” Riley says, and he means that literally. There are very few items in America—or anywhere else—that can make that claim.

501 Westminster Avenue • 573-592-5369 • NationalChurchillMuseum.org

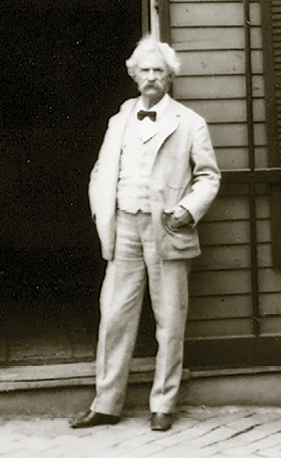

Mark Twain’s Jacket • Hannibal

Samuel Clemens left behind a pen name, some of the greatest books in American literature, enough pithy quotes to fill a dozen calendars, and a host of interesting items at The Mark Twain Boyhood Home & Museum in Hannibal.

One highlight is a white jacket that he was frequently photographed wearing. It is in a glass case alongside a gown he wore when he received an honorary degree from Oxford. The museum also has his pipe; a jewelry box he gave to his wife, Olivia; the death mask of his son, Langdon; and many other items.

120 North Main Street • 573-221-9010 • MarkTwainMuseum.org

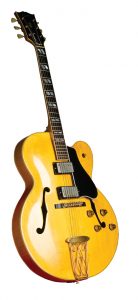

Chuck Berry’s Guitar • University City

Chuck Berry was the first person inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, and a collection of his artifacts is on display at Blueberry Hill in University City. Until his death in 2017, Berry played frequent shows at the popular restaurant, which is owned by his longtime friend Joe Edwards.

Berry’s guitar is in a glass case, along with a mold of his hands. Blueberry Hill calls it “the most influential Rock & Roll guitar in the world, the Gibson-350T with which Chuck Berry wrote, recorded, and performed his great classics such as ‘Rock and Roll Music,’ ‘Sweet Little Sixteen,’ and ‘Johnny B. Goode.’ ”

6504 Delmar Boulevard • 314-727-4444 • BlueberryHill.com

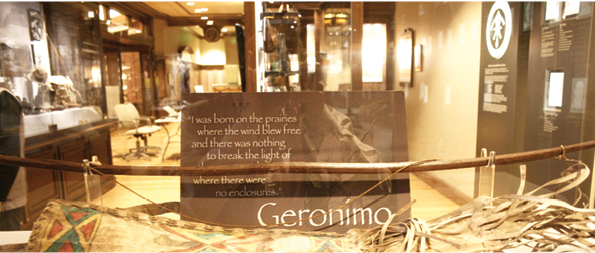

Geronimo’s Bow • Springfield

Within the building that houses Bass Pro Shops Outdoor World in Springfield, there are countless relics. Under one roof are the International Game Fish Association Fishing Hall of Fame, the Boone and Crockett Club’s National Collection of Heads and Horns, the NRA National Sporting Arms Museum, and Wonders of Wildlife. One of the treasures is a bow made by the famed Mescalero Chiricahua Apache Geronimo that is on display at the Archery Hall of Fame & Museum. Geronimo crafted the bow in the late 19th century while in captivity in Florida. Other highlights are guns used by John Wayne, Charlton Heston, and Theodore Roosevelt.

1935 South Campbell Avenue • 417-891-5346 • ArcheryHallOfFame.com

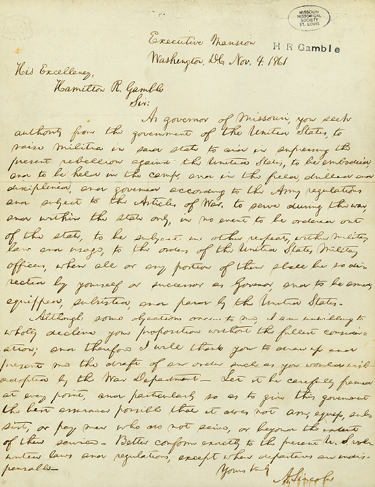

A Letter From Lincoln • St. Louis

The Missouri Historical Society owns many documents that have President Abraham Lincoln’s signature. But most of the text of those letters was written by a secretary. One letter—dated November 4, 1861, and addressed to Missouri Governor Hamilton Gamble—was written entirely by Lincoln. And visitors to the Missouri Historical Society Library and Research Center in St. Louis are allowed to hold that letter.

“When I show this letter to people, I always tell them to hold it while I talk about it,” archivist Molly Kodner wrote about the letter. “Often people are hesitant or even scared, but I insist they hold the letter because that’s the joy of using our archives collections. As they hold the letter, I remind them that it was a blank piece of paper until Abraham Lincoln sat down at his desk in the White House in 1861 to write it. I remind them that they’re holding a piece of paper Lincoln held all those years ago. I ask them to imagine what his office looked like at that time. Was he writing by candlelight or next to an open window that provided natural light? If he paused to look out the window, what did the world outside look like? A simple piece of paper can lead to so many questions, not only about the content of the text but also about the document itself.”

The library and research center also has and will let you hold what it jokingly calls Thomas Jefferson’s “driver’s license”—a permit to use one chariot, two phaetons, and one gig in the city of Washington. Items of note that are less accessible include an extensive collection relating to explorers Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, aviator Charles Lindbergh, and the 1904 World’s Fair.

225 South Skinker Boulevard • 314-746-4500 • MoHistory.org

The Fiddle That Belonged to Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Father • Mansfield

The Laura Ingalls Wilder Home used to take the fiddle out to be played only during Wilder Days in mid-September and a few other times a year. But that has changed recently. Now it is played a few times a month. (Call ahead to find out when.)

The origin of the fiddle is not 100 percent clear, but it is believed that Charles received it as a teenager after he or his family bought a certain amount of feed—the modern-day equivalent of a frequent flyer program, only instead of free airfare, he received a musical instrument that has since become more than just famous. It’s a relic that connects us to history. 3060 Route A • 877-924-7126 • LauraIngallsWilderHome.com

Related Posts

7 Missouri Waterfalls

A haven for gorgeous scenery, the Ozarks is brimming with stunning waterfalls. April and May are great months to enjoy our waterfalls, as water flow is at its peak from spring showers.

10 Books on Missouri’s Native American History

Looking for more reading on the Osage and Missouria tribes? Parts 2 and 3 of our special series are forthcoming in September and October, but in the mean time we highly recommend this selection of books that cover the subject.

Pickleball Is Taking Missouri By Storm

It took about a decade for pickleball to sweep Missouri. With more than 100 locations developed since 2010, Missouri might just have the fastest-growing pickleball community in the country.