When we step into our local city parks, the warm sun shining down on our skin, the fresh air entering our lungs, and the soft grass-covered earth below our feet satisfy some primal need inside of us. This was the observation that led luminaries like Frederick Law Olmstead to advocate for green spaces, such as New York City’s Central Park, which he designed. The city park and other municipal green spaces were designed to keep the city at bay. They allow an aspect of nature to exist in otherwise urban environments, providing a leisure environment free of charge, and giving humans who dwell in cities a lifeline back to the humble beginnings of our species.

The urban green space was conceptualized with benefits to mental health in mind, and the hypothesis that drove a wave of city parks to be created in America in the 19th century has been proven to be true many times over. The National Recreation and Parks System reports, “Several studies have confirmed that separation from nature is detrimental to human development, health, and well-being, and that regular contact with nature is required for good mental health.” Two of the country’s largest municipal parks are here in Missouri. They both carry a rich history, allowing you to step back in time and relax like those in the past. They give visitors an outlet for play, relaxation, and entertainment all year long.

Swope Park

In 1896, Kansas City philanthropist Thomas H. Swope donated a 1,334-acre plot of land along the Blue River for public use. The undeveloped land was named Swope Park. In the following years, the city developed a number of attractions on the donated land. In 1909 the Kansas City Zoo opened, spanning 60 acres. In 1934 the park developed a public golf course, and in 1951 the Starlight Theater opened showcasing world-famous entertainers under the night sky.

Although public parks serve as a gathering place for a city’s residents, not everyone has historically had equal access to these spaces. Swope Park is no different. In its early history there was only one shelter available for rental to black families. Shelter No. 5 was known throughout the black community as “Watermelon Hill,” an ode to the popular food residents brought to picnics. The swimming pool and golf course were also strictly segregated until a court order desegregated the pool on June 12, 1954.

Swope Park spans 1,805 acres today. It is the 51st-largest municipal park in the United States.

A large portion of the park is still heavily wooded and undeveloped, and hiking and biking trails wind through woodlands and grassy meadows encompassing soccer fields, golf courses, community gardens, and fountains as well as the Lakeside Nature Center, Missouri’s largest native species rehabilitation center. Swope Park offers something for everyone. During the day, the park hosts public activities in these open spaces, like the famous Ethnic Enrichment Festival, and at night, the music of Broadway musicals or major touring musicians ring out into the park.

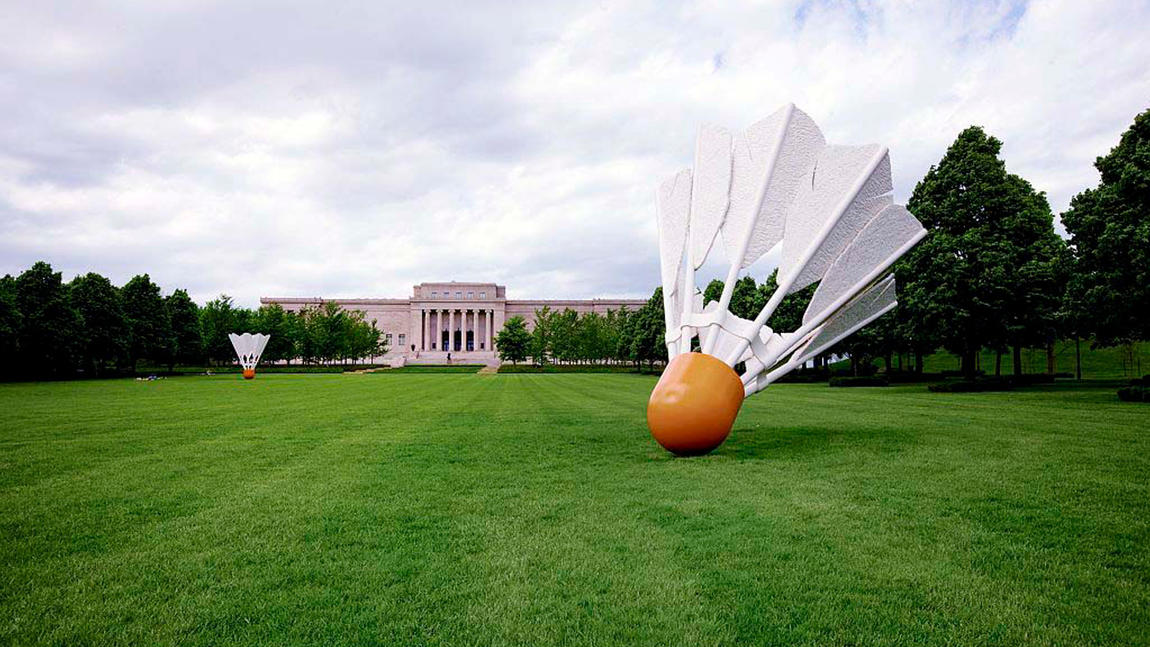

Forest Park

Forest Park began as a dense forest on the outskirts of downtown St. Louis. Built with the intent to match the grand public parks of Europe, Forest Park officially opened on June 24, 1876. Today the park exceeds New York City’s Central Park in size by more than 500 acres.

Forest Park’s most defining event took place in 1904. The Louisiana Purchase Exposition or World’s Fair was a grand international exhibition displaying innovations in industry, science, and culture from around the world. Hoping to seize this moment in the spotlight, St. Louis spared no expense in preparing for the fair, and Forest Park was the beating heart of the festivities. Nearly 1,500 buildings were erected across Forest Park’s newly redesigned 1,200 acres. Don Corrigan, author of the book Forest Park, explains the changes to the park due to the success of the World’s Fair. “The planners always had in mind they would bring the park back to where it was when the fair was over. They just couldn’t do that. It had changed the park so much. They [had] buried the Des Peres River, they built buildings that would stay, and they realized they had something good that shouldn’t disappear.”

Upon the fair’s closing in December of 1904, an estimated 20 million visitors had strolled through Forest Park over the seven month event. Proceeds from the fair later helped with the construction of the still-standing World’s Fair Pavilion in 1909.

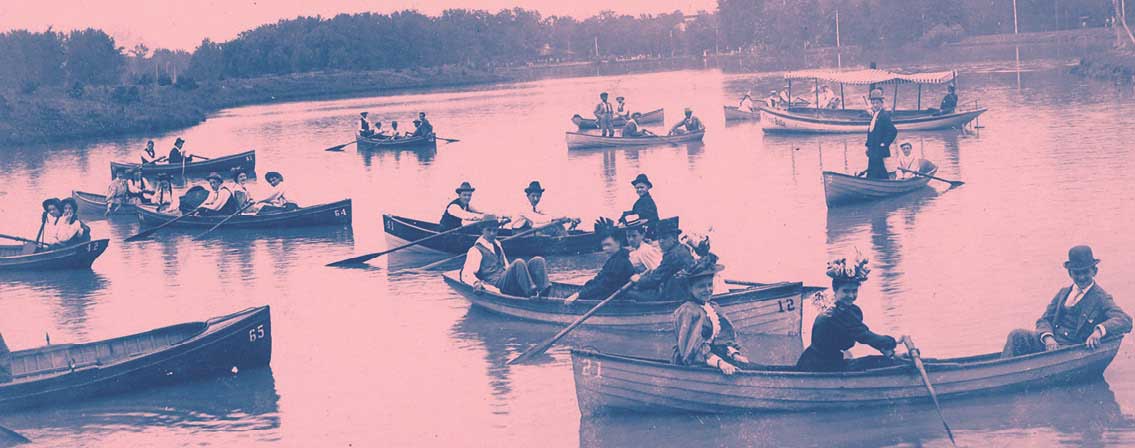

A trip to Forest Park is a historical adventure as much as it is a natural escape. No matter the season, the park offers space to unwind, whether sledding down Art Hill in the winter, on a paddle boat on the Grand Basin in the summer, or viewing over 30,000 pieces of art in the St. Louis Art Museum any time of year.

Related Posts

Missouri’s Largest Things

The Show-Me State—where we have to see it to believe it—boasts not one but three giant balls of twine, the world’s largest rocking chair, and a gargantuan goose amongst a host of other roadside stops. So get out your camera, fuel up, and take a road trip across the state to see Missouri’s largest attractions.

Ste. Genevieve to Become a National Historic Park

Ste. Genevieve was established in 1735 by French-Canadian colonists. It was the first ever settlement by Europeans in Missouri.

See Our Vanishing Roadside Parks

After some investigating, I found Karen Daniels, senior historic preservation specialist for the Missouri Department of Transportation. She’s the expert on the state’s roadside parks.