It’s natural to conjure up stories when you think about the Ozarks. Images of Bald Knobbers, mountain hermits, outlaws looking for a hideout are all but etched into the rugged face of the region. But for a long time, too long in the estimation of editor Phillip Douglas Howerton, the Ozarks have gone overlooked as an important American literary region.

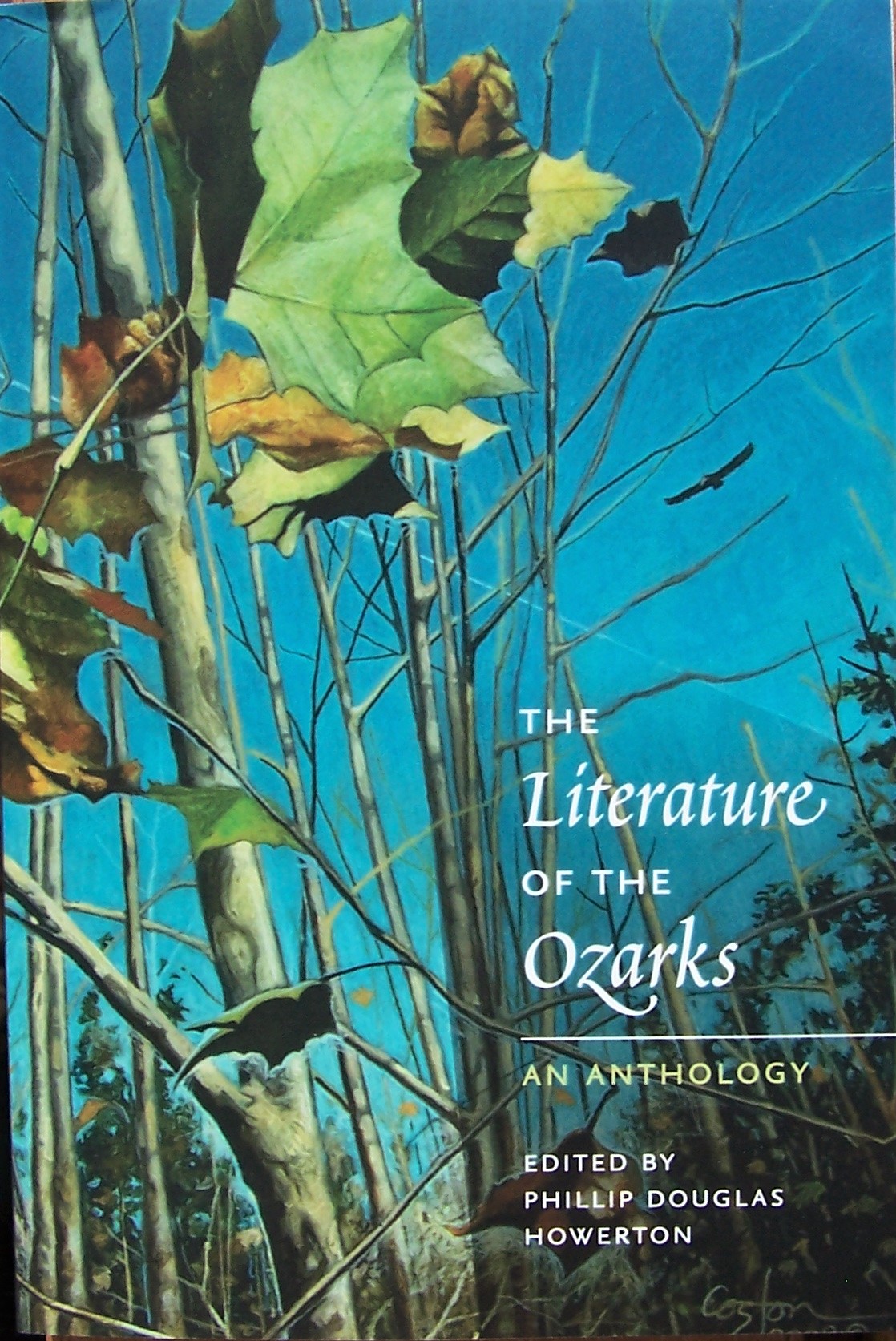

His book, The Literature of the Ozarks: An Anthology, in his words “seeks to begin remedying this lapse in scholarship.” In Howerton’s introduction he helps define the Ozarks culturally and geographically, and he nods to past anthologies that have collected Ozarks literature, but notes that none so far have covered its complete history.

Literature of the Ozarks is chunked into four sections, demarcated by date ranges. The first, Beginnings to 1865, contains a translation of an Osage oral tradition and excerpts from Henry Rowe Schoolcraft, among others. Further along one finds excerpts from Harold Bell Wright and Wilson Rawls, stretching along up to authors whose work has been reviewed in the pages of this magazine as recently as 2013, including Steve Yates.

Howerton defines the contents of the anthology as creative works of fiction and seminal nonfiction that comment on the social construction of the Ozarks, specifying notably: “regardless of their perceived literary worth and regardless of the author’s birthplace or familiarity with the region.”

A good example of how that plays out in practice is the inclusion of an excerpt from Harold Bell Wright’s Shepherd of the Hills, a novel that has been criticized both for its failings as a piece of literature and perceived inaccuracies in its depiction of the region. Wright, after all, was from New York. And yet it’s hard to think of a single writer, except maybe Schoolcraft for an earlier era and Daniel Woodrell, author of Winter’s Bone, for the current one, who did more to influence popular understanding of the Ozarks outside the region.

If you’re not a literature critic the book still has plenty of merits as a collection containing some excellent writing. It can also help you understand the history of the region; why some of the stereotypes we associate with the Ozarks took hold and where they came from. We may all soon be the benefactors of Howerton’s work if an increased profile for Ozarks literature inspires more great writing out of the region. Here’s hoping it does.

Related Posts

The Ozark Mountain Daredevils Are Still Shining

Springfield’s good old boys got to sing and sing and sing.