Make your way to the “cave park.” Take in the immense beauty as you float the river, stop by the visitor center and museum, check out the aquariums, and marvel at the geological wonders. Take a guided tour of one of the caves in the summer.

Photo by Ron Colatskie

ONE OF FIVE STATE PARKS ALONG THE MERAMEC River, Meramec State Park is one of the oldest, best known, and most popular of Missouri’s state parks. The other parks along the river are Onondaga Cave, Robertsville, Route 66, and Castlewood. At nearly 6,900 acres, this park is one of the largest in the state, lying across parts of Franklin, Crawford, and Washington Counties. The park is named for the river that flows eight miles through it and along its borders, which is fitting, as the Meramec River is the dominant natural influence over the park’s varied features. The river was also the centerpiece of a bitter public controversy resolved in favor of the free-flowing stream, one of the most biologically diverse in the Midwest.

The visitor center and museum, dedicated in 1989, provide an outstanding introduction to the park and the river. It has an educational and fun mix of exhibits and activities for people of all ages. Especially popular are the large aquariums that display the amazing variety of aquatic life in the river—from predatory bass to minnows of rainbow colors—with a clarity and closeness that you otherwise might not experience. Large murals and complex dioramas present the broad sweep of history, both human and natural, in the Meramec River valley.

A good way to enjoy the park is by river. The river has an undeserved reputation as being treacherous, probably because of accidental drownings on the lower, deeper sections near St. Louis. But the Meramec is as safe as any other Ozark stream. If you launch your boat at Sappington Bridge and take out down at Cane Bottom, you can see much of the park in a good day’s float or a more leisurely two-day float trip.

Photo Courtesy of Missouri State Parks

As you drift downstream, you will see Hamilton Creek coming in from the right. A bit more than a mile up this creek are the ruins of the old Hamilton Iron Furnace, not far from Hamilton Spring. The ironworks, one of many in the Meramec basin, was built in 1873 and was soon followed by a town that grew in size to some 150 people in the late 1880s. Ironworks are dependent upon the economy, and this one died young. It remains an intriguing site to visit, with the brick crucible still visible in the stone furnace and with the sites of several auxiliary structures still visible as well. The walking trail has signs identifying the features.

Beyond the mouth of Hamilton Creek, a massive dolomite cliff rises on the right bank. In the cliff is one of Missouri’s most impressive cave openings, Green’s Cave, well worth a stop. Wild caves such as Green’s are managed to protect the bats that hibernate in them. Some are closed and others are open, but always check with park staff before exploring.

At this point, the river makes a large bend to the left and then back to the right, which geologists call an entrenched meander. Such bends speak of the natural history of the area. Rivers on relatively flat terrain tend to meander, whereas rivers in rough terrain tend to follow a straighter course. Most of the Ozark rivers were formed when the area was a broad plateau, so they meandered back and forth. As the region slowly became elevated over millions of years, the rivers—meanders and all—cut their way into the dolomite bedrock, thus “entrenching” themselves.

This is a good place to see the hydrologic power of the Meramec. On the outside bend of the meander, the water relentlessly wears away soil and rock on the bank. Large sycamores that have been undercut wait to tumble into the stream with the next flood. On the inside bend, the opposite is occurring. Silt and chert gravel are being deposited, often forming large bars with willows and other plants anchoring the new alluvial land. You cannot see it, but the river actually flows in a corkscrew motion as it rounds the bend. The rugged landscape of this state park owes its character to the persistent force of the Meramec River over the eons.

Down a little farther, you float past what was to have been the site of the Meramec Park Dam. This controversial federal water project was effectively killed in 1978 when the public voted “no” by a margin of two to one in a regional, twelve-county referendum. Respecting the citizenry’s desires, elected officials deauthorized the project several years later. In fact, all of the state park land along the stretch of river just described had been purchased by the Army Corps of Engineers for the proposed 12,600-acre lake. The corps transferred several thousand acres of the land to the state for the park, along with a scenic easement, referred to by Ozarkers as a setback, of six hundred feet on each side of the river. Other lands were returned to private ownership through public auction.

Many factors figured into the dam’s demise, but one is worthy of mention here: caves. In addition to more than four dozen known caves in the park area, countless caves with no surface entry probably exist. Critics of the dam pointed out the cavernous nature of the hills that the earthen dam would have abutted, but Army engineers insisted that with enough concrete grout any cavity could be sealed. Drilling for a dam abutment accidentally confirmed a major cavern in one hillside, a cavern with chambers fifty feet high in places. Today that pristine cave, Moore’s Cave, is protected as part of the state park and is closed to the public. It can only be entered by rope through a hundred-foot shaft.

Meramec State Park traces its beginnings to 1927, when the State Game and Fish Commission started acquiring land along the river near the site of the old mining town, Reedsville. Indians and early French and American settlers had mined for lead, and later also for iron and copper. Some ten thousand people in two thousand cars reportedly attended the park dedication in 1928, and Meramec, with ready accessibility from St. Louis, quickly became one of the state’s most popular parks.

The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) built many of the facilities in the 1930s. Most of these structures, including the dining lodge, cabins, and river shelter, have been restored and are still in service. The vintage lodge offers a fine view of the river. Newer facilities such as the park store, the Hickory Ridge Conference Center, and the visitor center were designed to carry on the CCC heritage of handsome craftsmanship.

Near the riverside campground is the entrance to Fisher Cave, one of Missouri’s oldest show caves. The cave features many speleothems (rock forms) with troglobites and stygobites (cave creatures). Fisher Cave was key in the 1950s studies of prominent geologist J. Harlan Bretz when he was developing his theory of speleogenesis, or cave origin.

Photo by Shelly Colatskie.

State park naturalists conduct guided tours of the cave’s subterranean splendor in the summer. Fisher Cave was closed temporarily in an effort to slow the rapid spread of white-nose syndrome, a disease caused by a fungus that was unknown to science as recently as 2007 and that is highly lethal to certain species of bats that hibernate in caves. Rigorous screening measures are now in place in state park show caves to minimize the spread of the syndrome, and the caves are closed in other seasons when bats are present. Most wild caves that harbor bats have been closed year-round. Until the disease and its transmittal are better understood, scientists prefer to err on the side of caution.

Outside the caves, wildlife abounds in the park, and you will have a good chance of seeing ospreys, mink, or river otters. September is often the best month to be on the river. Typically, skies are sunny, both air and water temperatures are mild, and the river is clear and uncrowded. In mid-September, the peak of the hummingbird migration usually coincides with the peak blooming of the cardinal flower. This common riverside plant is so sought after by hummingbirds that you will rarely watch for five minutes before a hummer shows up.

Even at midday on a summer weekend, you can experience the rich diversity of the Meramec by putting on snorkeling goggles and sub- merging into the clear waters. With over one hundred species of fish and numerous species of turtles, salamanders, crawfish, and mussels, the Meramec is considered Missouri’s Amazon of aquatic life.

Back from the river is an extensive mature forest. On slopes that face east or north, the forest often reaches an impressive size and density. Here in early May, a healthy population of the exquisite yellow lady’s slipper orchid flourishes. On the south sides of several ridges are several thin-soiled rocky glade openings in the forest. In mid-April, red Indian paintbrush embellishes the glades. In early June, the long rays of purple coneflower blossoms unfold, providing a second peak of color.

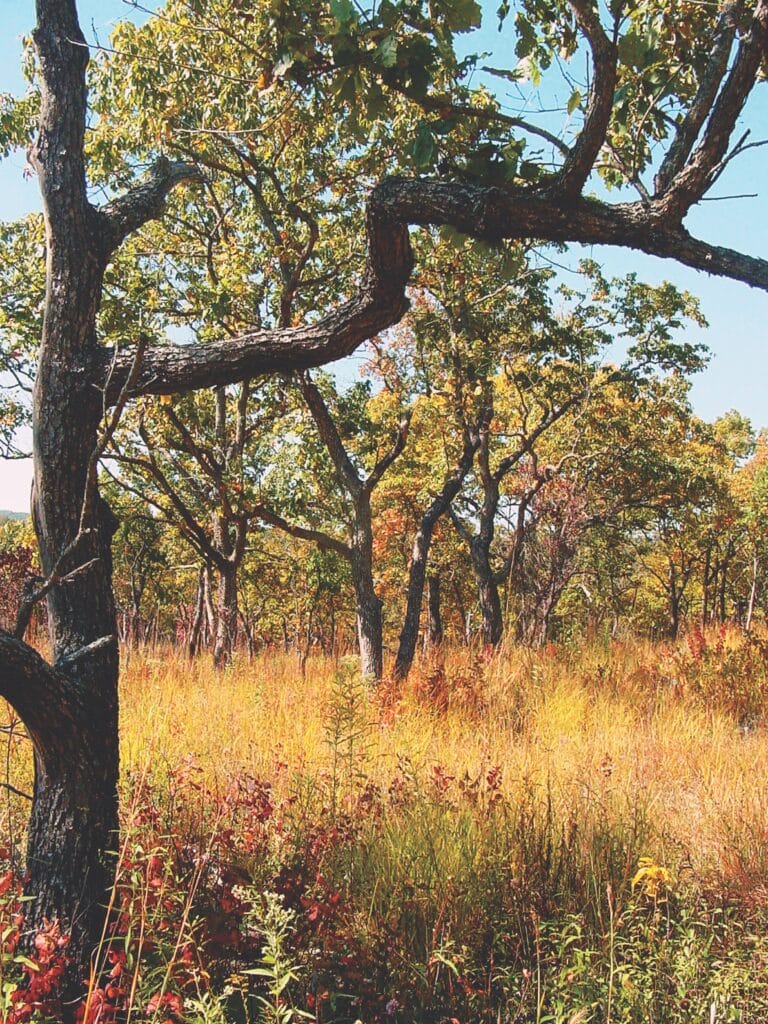

Photo by Paul Nelso

Some of the best places to experience the harmonious blend of glades and majestic trees are the park’s two natural areas, the 460-acre Meramec Upland Forest Natural Area and the 830-acre Meramec Mosaic Natural Area. They represent some of Missouri’s finest examples of the forest and woodland communities that typically grow on well-drained cherty soil formed from dolomite rock. Meramec Mosaic contains diverse natural communities, including fens, cliffs, caves, springs, creeks, lush bottomland forests and, on the uplands, woodlands with native grasses and gnarled chinkapin oaks and glades with dazzling wildflowers, thanks to stewardship by park staff and volunteers. The Mosaic area may be entered on the mile-long Natural Wonders Trail near the visitor center while the ten-mile Wilderness Trail traverses the more remote Upland Forest area and adjacent backcountry in the northern part of the park.

Although the woods and the caves provide an extra measure of enjoyment for a Meramec State Park outing, it is ultimately the river that defines not only the experience but also the park itself. Like one of the river’s meanders, the park has come nearly full circle, from its first modest attempt to preserve the riverine environs for the public, through the speculative fevers of dam construction, back to the real heart of the matter: the Meramec. The natural values of the river and its rugged watershed have prevailed.

Meramec State Park could well be called “the cave park” as it has some four dozen named caves within its boundaries—more than any other state park in Missouri and second in the nation.

MERAMEC STATE PARK • 115 MERAMEC PARK DRIVE, SULLIVAN

Related Posts

A True Gem of a State Park

Dedicated in 1938, this gem of a state park now sits amid an expanding suburban landscape and is worthy of a visit any time of year. There are twenty-two CCC-era structures to visit, rocky hills to hike, and massive trees to stop and rest under.

A Campfire Dinner at Babler State Park

Matt Crossman loves to take his kids camping at beautiful Babler State Park in Wildwood. On a recent trip, he earned raves from picky eaters with a classic campfire dish. Learn what goes inside (spoiler alert: ANYTHING!) this tasty treat.

Hiking Graham Cave State Park

Head over to Graham Cave State Park to walk in the footsteps of early Missourians.