Anyone, but especially young people, can find new inspiration in Jefferson City.

A few blocks from the Capitol sits a museum that is bringing Smithsonian-worthy modern art to the middle of Missouri—and it’s doing it with a purpose.

Opened in October 2015, the Jefferson City Museum of Modern Art features the works of Purvis Young, Thornton Dial, and Abdoulaye Diarrassouba, better known as Aboudia. All have earned national and international acclaim for their art, which can be found in some of the country’s most distinguished museums.

The three artists traveled difficult journeys to fame. Each faced immense adversity in his youth but overcame it to create something beautiful, and that’s where the heart of JCMoMA lies. Offering free, guided tours for school groups and other organizations, the museum has made it its mission to remind young people that they, like the artists featured, can achieve anything. By bringing quality art to kids who might never make it to a New York or Washington, DC, museum, JCMoMA both inspires and educates Missouri youth. “It’s a treasure hidden in Jefferson City,” says museum docent Chris Duren.

JCMoMA’s story began when Richard Howerton stumbled across a Purvis Young painting at a gallery in Florida. He bought it, and when he took it to a framer, he was told, “Oh my, that’s a Purvis Young.”

Richard’s interest was sparked. He began reading about Purvis. Inspired by his struggles with poverty and homelessness, Richard bought Purvis Young works until he had a small collection and decided to open a museum in his hometown of Jefferson City.

Richard knew from the start that the High Street museum wouldn’t be typical. He wouldn’t have regular hours. He wouldn’t routinely switch out old pieces with new ones. And he wouldn’t cater to the classic audience—adults. Instead, he opted to feature only abstract expressionist artists who had faced challenges in their youth, and he would use their stories and art to inspire and educate young people.

So far, he’s found three artists who fit that mission.

Purvis Young

A prolific painter, Purvis Young’s artwork accounts for the majority of the JCMoMA collection. Richard acquired many of the pieces from a collector in Florida who had known him. Purvis painted so much that his thousands of works were stored in boxes, piled one on top of the other. Several of the pieces Richard purchased had never been seen by the rest of the world prior to their move to JCMoMA.

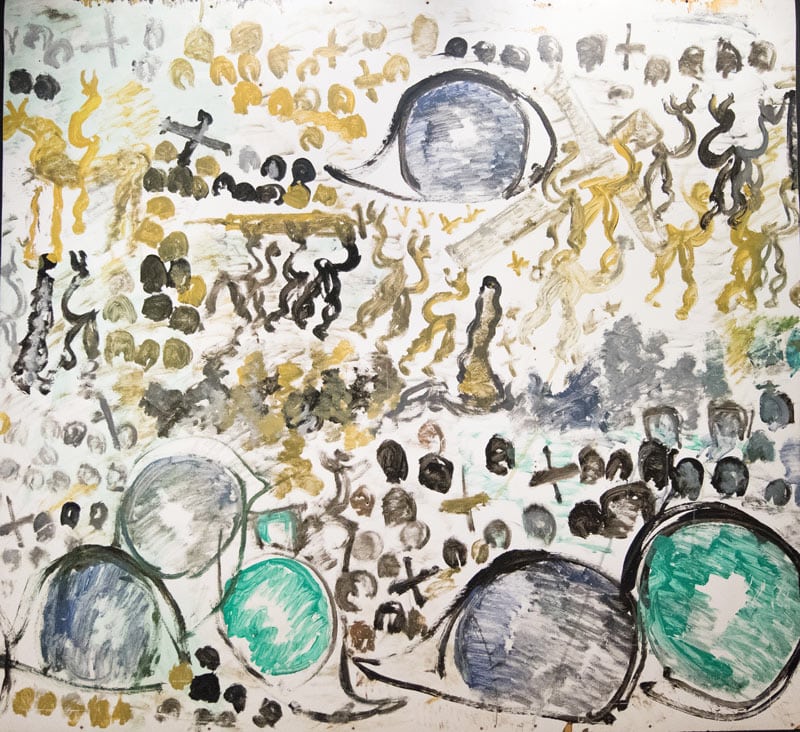

Purvis, who died in 2010, didn’t attend high school and spent three years as a teenager in prison, where he began sketching. After prison, he lived homeless in a poor part of Miami called Overtown. With no money but a love of painting, Purvis began creating art with whatever objects he could find—discarded doors, house paint, old magazines, torn book pages, and more. He would spend 10 to 12 hours a day in an abandoned warehouse producing piece after piece.

His work often conveys the world as he saw it in his city, fraught with poverty, addiction, and violence. It’s messy, Chris says, but much of what looks like scribbles in his work are actually symbols repeated over and over in all of his art. Asterisks symbolize the heavens. Horses symbolize freedom. Rectangles and half ovals symbolize caskets and tombstones, and a squiggly line with two lines radiating from the top and bottom symbolizes angels on Earth.

These symbols come together in his works to tell a story. In e Eyes of the System Just Watching, Purvis depicts dark figures carrying drugs into neighborhoods and chasing out the good people. Tombstones appear throughout, and eyes at the bottom represent the rest of the world—people who have the power to do something about it—just watching.

His works appear in museums throughout the country, including the Smithsonian Institution.

Thorton Dial

Like Purvis, Thornton Dial, who died in 2016, was a self-taught artist who struggled with poverty. He was born to sharecroppers in rural Alabama. He attended school briefly and labored in various jobs, creating art in his free time.

Thornton used whatever he could find to make his art—including animal bones and scrap metal. He couldn’t get paper, so he made his own, museum docent Jennifer Milne says. Thornton, who could neither read nor write, signed his works, “TD.”

Thornton is best known for his sculptures, but JCMoMA features many of his paintings, which tend to focus on black life. Tigers appear as a symbol for the struggle of black people in this country. His art tells stories of events and his feelings about them. Coming out of the Hills depicts Martin Luther King Jr.’s march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, which Thornton witnessed. The painting is upside down to represent Thornton’s view that, “if you’d seen the march, you’d think the whole world was upside down,” Richard says. “Things were changing.”

Thornton’s works are in the Smithsonian and New York’s Museum of Modern Art.

Aboudia

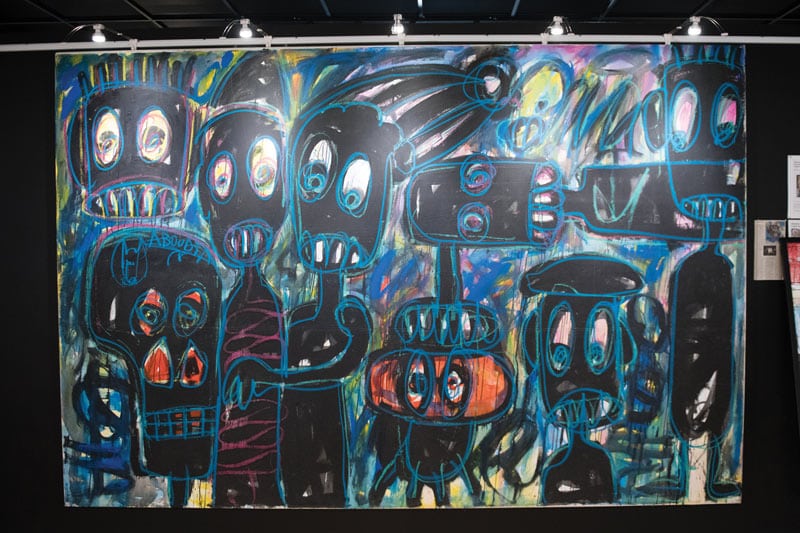

Young and up-and-coming in the art world, Aboudia is the only artist featured in JCMoMA who is not an “outsider artist”—that is, he actually received formal training in art. That education didn’t come easy.

Abdoulaye Diarrassouba was born in West Africa’s tumultuous Ivory Coast. When he told his father he wanted to be an artist, his dad said he needed a “real job.” When he asked professors about studying art in college, Chris says, they told him, “Kids who come from where you come from end up on the street.” Aboudia graduated with a degree in mural art and gained broad recognition; the Huffington Post named him one of the 10 African artists to know in 2015. Much of

Aboudia’s work reflects the chaos he has witnessed in his country during the Second Ivorian Civil War, which began in 2011. His one painting at JCMoMA—a huge, colorful work that immediately attracts all who enter — depicts the street children of Abidjan. These children live and die on the streets, Jennifer says. The painting shows the horrors of war in its depictions of the children grimacing and holding one another, terrified by their world, she says.

Aboudia’s art has been exhibited around the world, including in the Jack Bell Gallery in London.

Messages of Art

Groups touring JCMoMA hear about these artists, their work, and the meanings behind their art.

“It’s just great to tell kids, ‘Hey, no matter what kind of talent you have, whether you have supplies or not, you can fulfill your dreams by not giving up and just fulfilling your passions,’” Chris says.

The art is inspiring, but it’s also educational.

“All three of these men tell history,” Jennifer says. “They tell what it was like to live in an urban area, what it was like to be a black man in America, or what it is like to see your country ravaged by war.”

Richard hopes to keep growing his collection. He’s continually searching for other diverse, modern artists whose art and their journeys to it will inspire others as these three artists have inspired him.

Although the museum focuses on students, it’s open to all organizations. To schedule a tour, call 573-635- 1114. Find out more at JCMoMA.com.

Related Posts

Learn to Throw an Axe in Kansas City

Taking the outdoors to the West Bottoms, two entrepreneurs have brought urban axe throwing to Kansas City. Blade & Timber founders Matt Baysinger and Ryan Henrich got their start in the escape room business with Breakout KC.

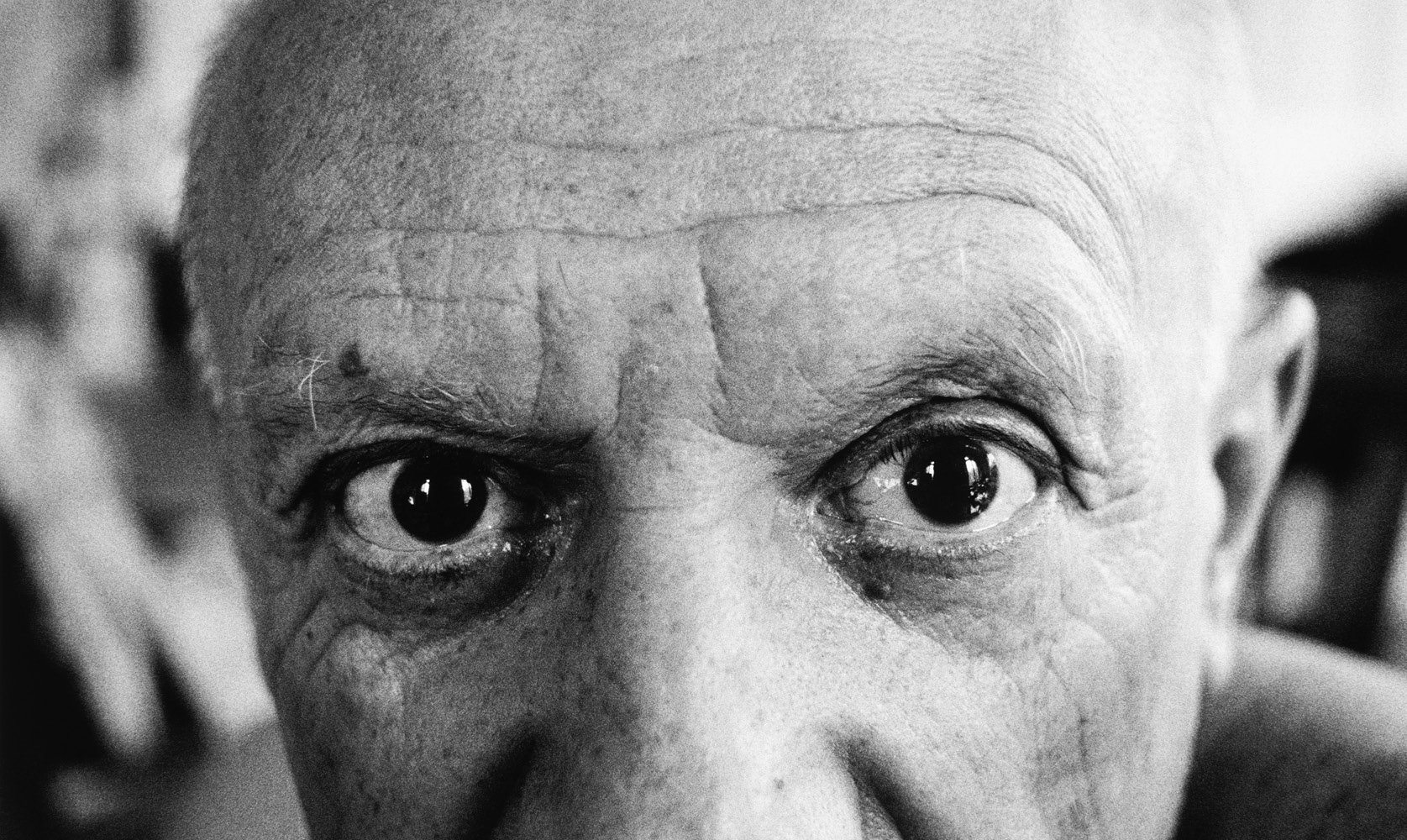

Picasso Comes to Kansas City

Missouri Life Magazine publishes articles relating to Missouri culture, subscribe today. See the beautiful work of Picasso in Kansas City