This article was originally published in our June 2021 issue.

I traveled along Milita Drive in southeast Jefferson City, looking forward to meeting with the artist Essex Garner, a veteran of both the US military and the Missouri National Guard.

He had a recent exhibition of his military-themed artwork on display at the National Guard Headquarters, and as I approached the entrance, I saw Essex at the door with a contingent of his art students from Lincoln University.

Born in Kansas City in 1961, Essex became interested in art early in life. As a youth, he had an internship at Hallmark cards and participated in programs at the Kansas City Art Institute and the Art Research Center of Kansas City. After joining the armed forces, he worked as a military artist and illustrator, spending twenty-seven years serving his country, the last twenty of which were with the Missouri National Guard. While serving in the Guard, he earned a bachelor of fine arts degree from Lincoln University in 2006, and in 2012 he received a master’s degree in education from the University of Missouri with an emphasis in art education. Since 2010 he has served on the fine arts faculty of Lincoln University in Jefferson City, and education remains a central aspect of his life and art.

Here at the Missouri National Guard Headquarters, Essex wears a cap that distinguishes him as a retired Sgt. 1st Class with the Guard. He begins speaking about the artworks in the display, organized by Charles Machon, director of the nearby Missouri Military History Museum. It soon becomes clear that these works not only provide aesthetic models for Lincoln University art students but also provide lessons in history—most particularly lessons in the changing nature of historical memory. When confronted with Essex’s pictures, many viewers may find themselves reconsidering their preconceptions about America’s military history and wondering if racial stereotypes have shaped traditional perceptions about the past.

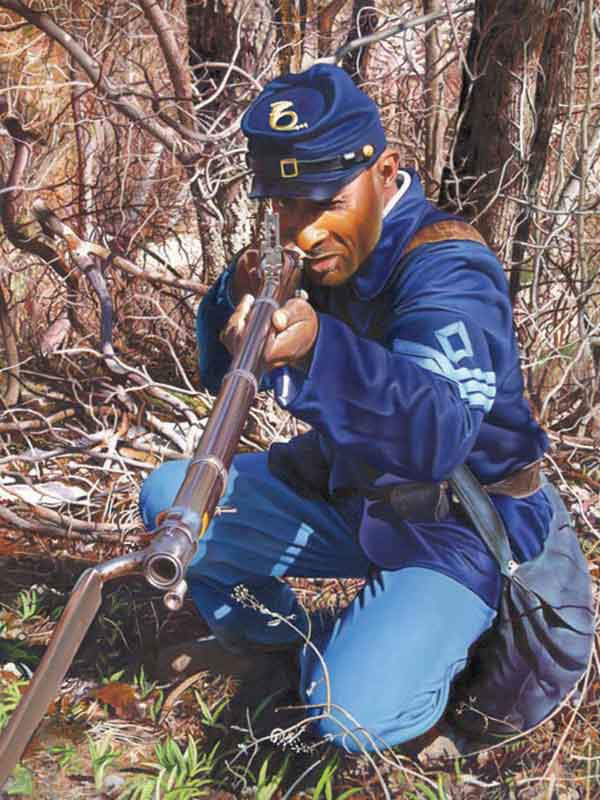

I join the Lincoln students as they peruse the exhibition. The artworks on display represent the historical involvement of African Americans in the US military during the 1800s. Some images depict Union soldiers from the Civil War era, while others represent the Buffalo Soldiers who patrolled the American West in the later nineteenth century. As I look at the pictures with the students, Essex informs us that he used himself as the model for the earliest of these artworks, Dead Reckoning. This picture was painted in 2011, the year that marked the 150th anniversary of the beginning of the American Civil War. It shows an African American Union soldier in training, and Essex explains that he worked hard to create a visually authentic image. He purchased a high-quality replica of a Union soldier’s uniform and borrowed a Civil War-era rifle. As he speaks about this picture, I am struck by the way Dead Reckoning subverts conventional expectations about Civil War art. Instead of picturing a dramatic clash of rebel and Union forces, this image depicts a single Black soldier whose future depends on the outcome of the conflict. The image focuses attention on the agency of the individual. This soldier is empowered. He holds a gun and is ready to fire. He is ready to change history.

Most of Essex’s artworks subvert traditional ways of representing history in one way or another. This is especially true of the watercolor, Things that Make You Go Hhhmm, which depicts two Black Union soldiers anachronistically examining Ed Dwight’s bronze Soldiers Memorial on the campus of Lincoln University in Jefferson City. Essex’s two-dimensional image participates in a visual dialogue with the three-dimensional sculpture, which depicts the Civil War veterans of the 62nd and 65th Colored Infantries. In 1866, these soldiers helped found Lincoln University, one of America’s earliest Black colleges.

Like Essex, the sculptor who made the Soldiers Memorial is also an African American veteran and born in Kansas City, but on the Kansas side. From 1953 until 1966, Captain Ed Dwight served in the US Air Force. While training as a test pilot, he earned a degree in aeronautical engineering and was chosen by President John F. Kennedy’s administration to begin pre-astronaut training in 1961. He completed the experimental test pilot course and the aerospace research pilot training, but three years after Kennedy’s assassination in 1963, facing harassment and discrimination, Dwight left the military. In the 1970s, he began a new career as an artist in Colorado. He has since gained national acclaim for his sculptures and memorials.

One can see Dwight’s Soldiers Memorial as a visualization of the famous William Faulkner quote, “The past is never dead, it’s not even past.” Some of the memorial’s bronze soldiers stand on a stone pedestal, while others appear to walk amongst the people in the surrounding plaza. On the pedestal, one bronze figure leans over to take the hand of a fellow soldier and appears ready to lift his companion onto the stone plinth. Dwight visualizes the initiative and self-determination of these soldiers as alive in the present. These figures from the past seem to interact in our space and in our time, memorializing themselves before our very eyes.

Essex is a friend and admirer of Dwight, and he responds to the latter’s Soldiers Memorial with a memorial of his own. In the painting Things That Make You Go Hhhmm (above), Essex imaginatively “resurrects” two veterans of the Colored Infantry. He depicts these Civil War vets examining one of Dwight’s bronze figures. This “meta-memorial” (a memorial about a memorial) encourages us to imagine how these historic figures might have responded to being memorialized. As we consider that question, we may also find ourselves asking why it took until 2007 for Dwight’s memorial to be erected, and why Essex’s time-traveling members of the US Colored Troops might be surprised to find themselves commemorated in bronze. By encouraging us to contemplate such questions, the painting reminds us of the newness of both Ed Dwight’s and Essex’s images—both are artworks that reinsert Black protagonists into the American historical narrative after decades of dominant culture neglect.

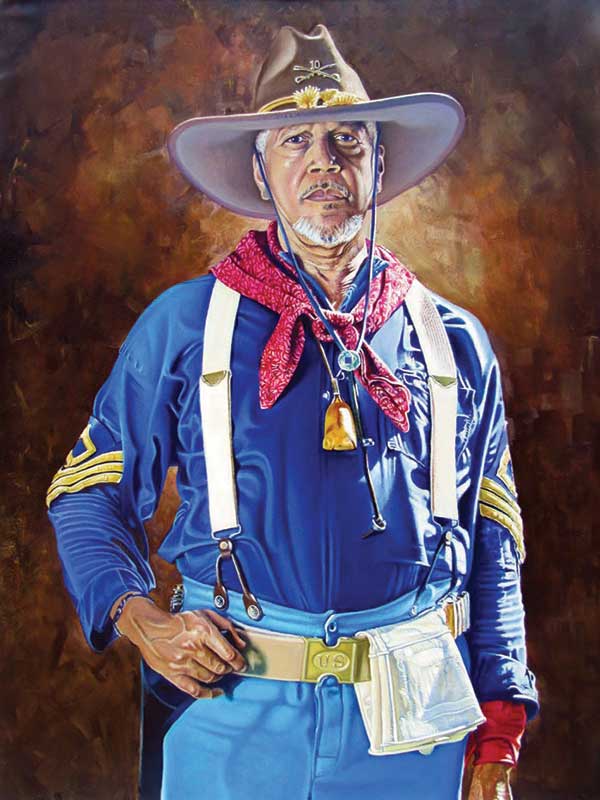

Essex’s interest in reviving the past led him to befriend a group of historical reenactors in Kansas City who belong to the Alexander/ Madison chapter of Kansas City Buffalo Soldiers. In 1866, the US government established six regiments of African American servicemen to be stationed in the American West. These troops came to be known as “Buffalo Soldiers,” and they protected western mail routes, patrolled America’s earliest national parks, and helped establish order on the frontier. The Kansas City reenactors preserve the legacy of these military pioneers, and like Essex, many are veterans who see the Buffalo Soldiers as their too-often-forgotten forebears.

Essex sometimes dons his replica Union uniform and joins the Kansas City Buffalo Soldiers in educational presentations, commemorative activities, and community events. The group is a cavalry unit, and many members ride horses as their predecessors did. Essex has ridden with them. The Missouri National Guard exhibition includes a dramatic equestrian image, Colorado Pass (2015), that depicts some of the Kansas City reenactors riding through a rocky western landscape, but it is the exhibition’s most recent picture, Traveler: Time of the MOJO, which presents the image that I find most compelling. The model for this painting is the current executive vice president of the Kansas City Buffalo Soldiers, George Pettigrew, a certified oral storyteller. He stands with one hand on his hip in a pose reminiscent of a hero from a Hollywood western. We can interpret the title as a literal allusion to Pettigrew, who metaphorically “travels” through time as a reenactor. The title, however, can also be understood as describing an anonymous nineteenth-century Buffalo Soldier who travels into our own time to be “resurrected” by Essex’s brush, with some help from Pettigrew.

Until recently, it has been rare to see African Americans represented in the popular media’s vision of the west, despite the fact that historians estimate that up to 25 percent of nineteenth-century cowboys were Black. Some of these Black cowboys were former Buffalo Soldiers, and the Kansas City reenactors make sure we remember them.

The act of visualizing history is a powerful societal tool. Essex and the reenactors are among the many people finding creative ways to help Americans re-envision the past. Many of these new visions of history not only include African Americans, but emphasize them in the foregrounds of visual genres traditionally associated with Euro-American art and history.

See Essex Garner’s work on display at Bruce R. Watkins Cultural Center, 3700 Blue Parkway, Kansas City, and at Memorial Hall at Lincoln University, 818 Chestnut Street, Jefferson City.

Related Posts

The Craft of Pipe Making

Learn how Missouri Meerschaum makes the beloved corn cob pipes that Washington, Missouri is known for.

Columbia Cherishes its Past

Columbia always has an eye on its future, but it cherishes the stories of its past. You can get an in-person glimpse of history at these Columbia locales.