Missouri wineries produce many pop-worthy bottles each year, according to world-renowned wine expert and Kansas City resident Doug Frost. He recommends sparkling wines from seven of our state’s wineries. “I’m quite fond of Les Bourgeois sparkling wines,” he says. “Hermannhof also makes a nice Brut Reserve. St. James, Crown Valley, and Mount Pleasant are making good sparkling wines. And Pirtle Winery makes a sparkling mead. Mead is an ancient beverage, not a wine in a classic sense. It’s made from fermented honey and has a very floral, aromatic character. It tastes like honey, and honey comes in all kinds of flavors. Theirs is quite nice.”

The most famous of all Missouri’s sparkling wines are produced by Stone Hill Winery in Hermann, which has been fine-tuning its craft longer than anyone else in the state. Doug describes these sparklers as having “pear, apple, or citrus flavors with a nice, clean finish.” He is especially fond of Stone Hill’s brut-style Blanc de Blancs. “I think that it has a great deal of flavor,” he says, pronouncing it “very clean and refreshing.”

Named Best Sparkling Wine at the 2018 Missouri Wine Competition, Stone Hill’s 2013 Blanc de Blancs comes from Vidal grapes, naturally fermented in the bottle and riddled by hand after aging on the yeast for about three years. Riddling is a process of both rotating and tilting the bottle so sediment gathers in the neck. The sediment is then frozen and removed or “disgorged” from the bottle.

Nothing says celebration quite like popping the cork on a bottle of sparkling wine. For New Year’s, Valentine’s Day, weddings, football championships, or christening new boats, sparkling wine is the way we cheer for ourselves, friends, family, and community. But do we have to wait for a special occasion to raise a glass of bubbly, or could we consider sparkling wine for more than celebrating?

Rare Vintage

Wine consultant Doug Frost is a Kansas City resident and one of only four people in the world to have passed both the Master Sommelier and Master of Wine examinations. He is president of the Institute of Masters of Wine North America and the author of many books: Uncorking Wine, a textbook for restaurant staff; On Wine, a witty look at wine knowledge; and Far From Ordinary: The Spanish Wine Guide. Kansas Citians know him as the host of Check Please! Kansas City, a restaurant review program that ran for four seasons on local PBS stations and still airs in reruns.

Jon Held was a young man in the early 1980s when his father, Jim, who founded Stone Hill Winery, brought winemaker Dave Johnson onboard to begin producing sparkling wines. Jim had been shipping tankers of Catawba, a native grape-varietal juice, to New York. In that state, wineries were turning it into sparkling wine with great success. Jim, Dave, and Jon began attending US symposiums on sparkling wine production and reading literature on the topic.

“As we were first learning, we didn’t have all the subtle nuances figured out,” Jon says. “The challenge was getting the sugar amount correct—bottles were exploding. We had to add a precise amount of sugar and very active yeast and bottle it quickly.”

Sparkling wines are incredibly difficult to make correctly, Doug says. “Winemakers must have a profound understanding of the chemistry throughout the process,” he asserts. “You end up with the same kind of pressure inside a bottle that is inside a tire. You better know what you’re doing, or there could be mistakes and broken bottles.”

To make a sparkling wine, vintners must first make a table wine that contains less-than-average alcohol content. The reason is that this wine undergoes a second fermentation that increases its alcohol percentage. “Most table wines from California contain about 14 percent alcohol,” Doug says. “You would never want to start with that to make a sparkling wine. You’re going to want to create a wine with less than 10 percent alcohol.”

Winemakers put that lower-alcohol table wine, called cuvée, in a tank, and create a second fermentation. “Or, at the very pinnacle of sparkling winemaking, you would do that inside the individual bottle,” Doug says, explaining that fermentation inside the bottle is both as simple, and as complex, as adding more yeast and sugar.

“If you know what you’re doing, the yeast will consume all the additional sugar,” he explains. “Yeast converts sugar into carbon dioxide bubbles. Winemakers need to know the precise amounts of both yeast and sugar, and then control the environment so the carbon dioxide stays in the wine and doesn’t escape.”

The style of sparkling wine determines whether yeast cells are left in the bottle. “They look like a kind of sediment but also impart flavor and character,” Doug says. “Or, you might do it in a vessel, filter out that yeast sediment and bottle it right away so it’s nice and fresh and fruity. It depends upon what style you’re trying to make.”

In Missouri, wineries usually strive for sparkling wines that taste fruity, unlike standard champagne. For example, champagne—the sparkling wine produced in the Champagne region of France—usually “spends years on the yeast cells, gathering flavors that are unusual and complex,” Doug says. “That’s why most of those wines are so expensive. In Missouri, the way is to not leave them on yeast cells very long.”

Doug believes there is a popular misconception that Missouri sparkling wines are always sweet—not to say there is anything wrong with a sweet wine. “There is an unfortunate view, usually held by people who are less informed, that sweet wines are less serious than dry wines,” he says.

Almost all sparkling wines have some sweetness to them, but the level can vary. The zesty fruitiness sometimes derives from the grapes themselves, and sometimes from the addition of cane sugar. High-end champagnes from France are usually sweetened as well, but in Doug’s experience, Missouri’s sparkling wines are neither too sweet nor cloying.

Americans have typically viewed sparkling wines as a special-occasion wine, not a typical before-dinner wine as they do in Germany or France.

But that attitude is slowly changing. Missouri’s sparkling wines are high quality and affordable, so you don’t need to save them for celebrations. Having lasagna for dinner? Live a little—and pop the cork!

Related Posts

Meet 5 of Our State’s Female Winemakers

Females fuel America’s wine industry: women buy 57 percent of the wine consumed in this country. But the ladies are not only buying and drinking wine; they’re making it, too.

Paddleboarding in the Show-Me State: Where, How, and Why

“Stand-up paddling is one of the fastest-growing water sports in the world,” says Don Dutton, owner of Going Coastal, a stand-up paddleboard retailer at the Lake of the Ozarks. “A decade ago, paddleboarding was virtually nonexistent in Missouri. In 2012, Going Coastal was the first company to sell paddleboards at the Lake of the Ozarks.”

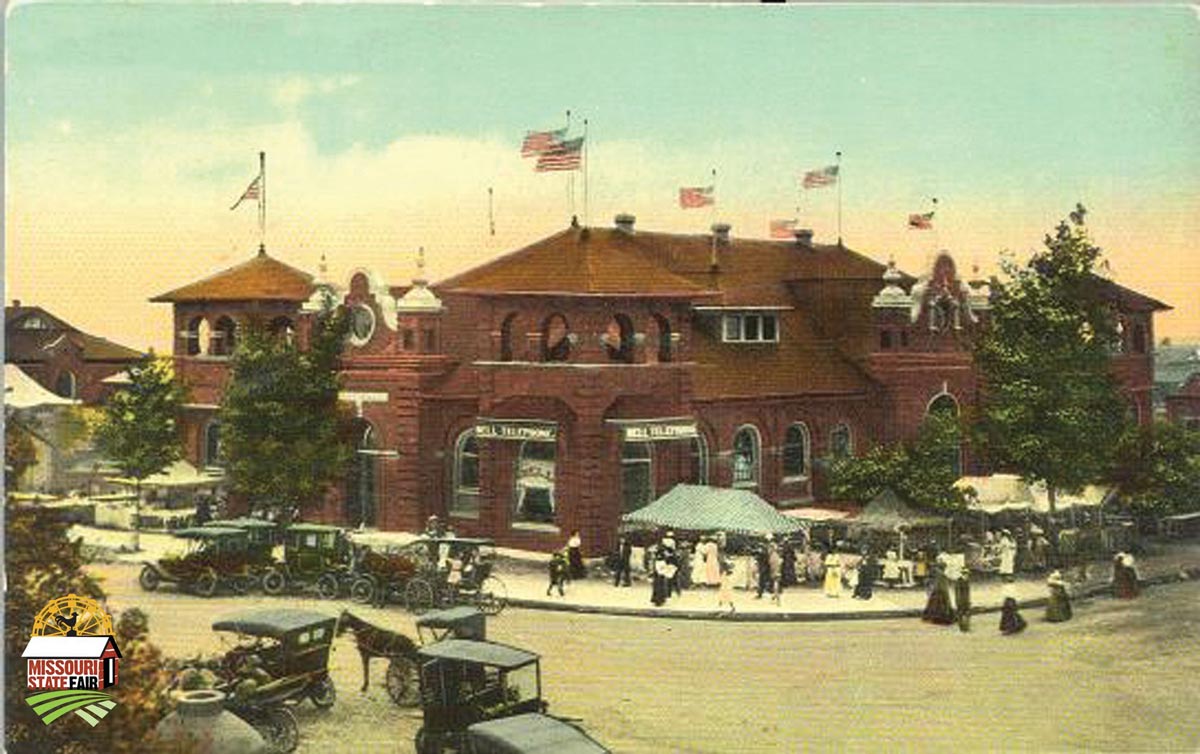

7 Time-Honored State Fair Traditions

Each year there’s something new to see, and yet some components of the Fair date back from before Missouri actually had a designated State Fair. Let’s take a walk through time and look at some of the State Fair’s most proud traditions.