“You have brought more freshness, charm, and vitality to illustration than any other living illustrator.

Now at last I have said it, and I feel much better because I have been believing this for a long, long time.”

Norman Rockwell wrote these words in a letter to graphic illustrator Al Parker in 1948. Known as the Dean of Illustrators, Parker was a modern master. His drawings graced the pages of all sorts of prominent publications that defined glamour in the golden age of magazines and advertising.

“I think he definitely exemplifies that golden era of illustration in the lateforties, fifties, and early-sixties,” says Skye Lacerte, curator of the Modern Graphic History Library at Washington University in St. Louis, a research library that houses much of Parker’s work and work from other graphic artists, such as Robert Andrew Parker, Robert Weaver, and Charles Craver.

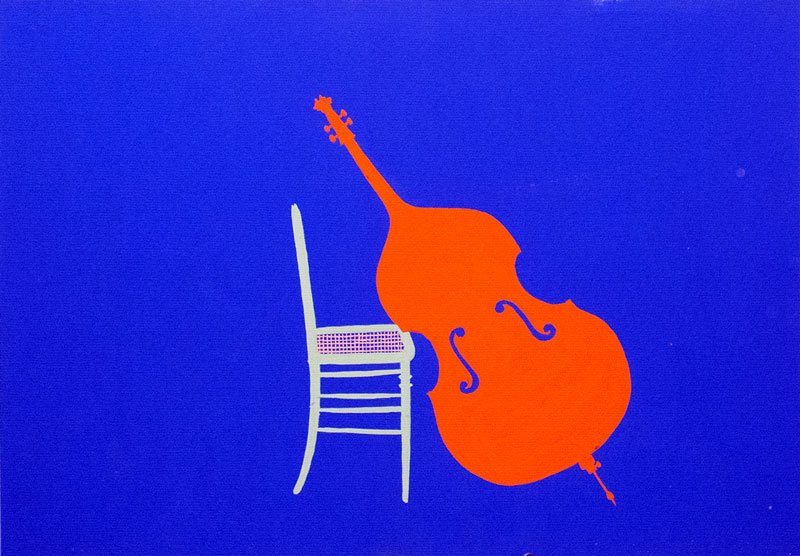

Parker’s early life was immersed in art. Born in St. Louis on October 16, 1906, Parker began drawing at a very young age, and his parents, who owned a furniture store, encouraged his creativity. His mother was also a musician, and his father was an aspiring painter.

In his teenage years, Parker took up the saxophone, and he eventually led his own band that would play on the Golden Eagle, a riverboat in Cape Girardeau, among other ships on the Mississippi. He performed for years and even played with jazz legend Louis Armstrong before the young artist attended Washington University to study fine arts.

Upon graduation, Parker started working in St. Louis. His first assignment was to design window displays for a local department store. Wallace Bassford, the head of a commercial art studio and a fellow Wash U alum, was taken with the design and contracted Parker to work for him. However, Parker set out to start his business with designer Russel Viehman soon after.

In 1930, Parker’s submission to a cover contest for House Beautiful garnered attention from the publishing industry. In the early 1930s, he began receiving a steady stream of work from magazines like Woman’s Home Companion, Good Housekeeping, McCall’s, Collier’s, Cosmopolitan, American, and Pictorial Review during a time when jobs were scarce—the Great Depression.

In 1936, Parker and his family left the Show-Me State in favor of New York City, the center of American publishing. In the 1940s, he began one of the most famous cover series for Ladies’ Home Journal. He illustrated wholesome pictures of a mother and daughter in an era defined by World War II, and the July 1945 cover showed the two welcoming home their hero.

“What’s neat about that is that people not only started following what was going on inside the magazines, but there were fans of these covers,” Skye says. “They would write in fan mail and ask questions about what the family is doing.”

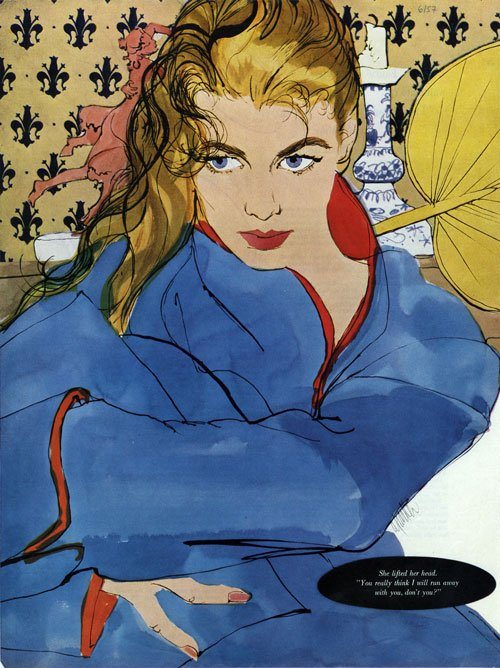

The mother and daughter series ended in 1952, but Parker adapted to the changing times. In 1954, Parker’s illustrations were the stars of the September issue of Cosmopolitan. He illustrated five fiction stories, each with a different style, showing his range.

During the sixties, magazine illustration began falling out of fashion, while photography saw its rise. Magazines that relied heavily on illustrations like the Saturday Evening Post and The Woman’s Home Companion ceased publishing by the end of the decade. Parker still found work at magazines such as Sports Illustrated and Fortune, again adapting his style to the times.

“When photography was starting to take over, he was able to continue illustrating because he was so adaptable,” Skye says.

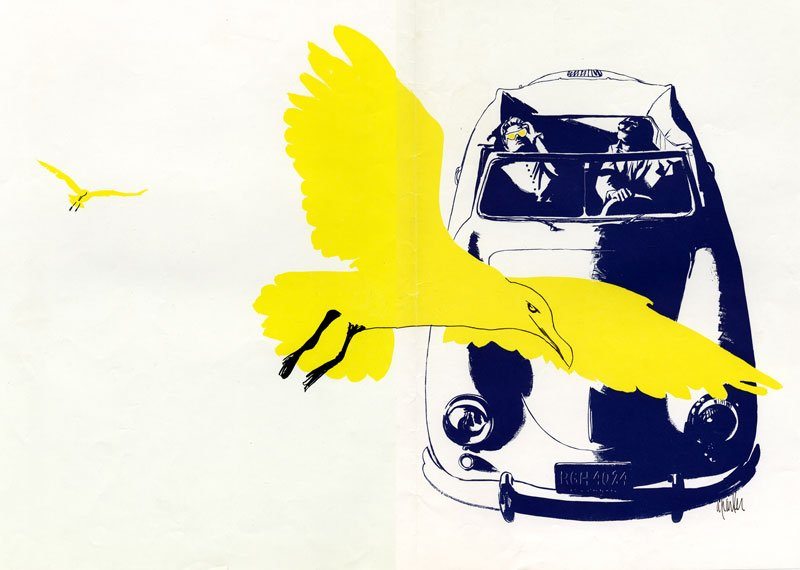

Although the golden era of magazine illustrations saw its twilight, Parker continued to illustrate for both editorial and advertising purposes throughout the 1980s. He also painted and drew for purely artistic purposes. Although he may be best known for his classic magazine illustrations, Parker continually evolved during his expansive career, experimenting with styles that took cues from Japanese prints to ones that were more expressive and vibrant.

“I think he probably got bored doing the same thing, so it was probably a mixture of the industry changing and pushing himself,” Skye says.

After Al Parker died in 1985, much of his work sat in a garage. However, in 2007, the family donated the collection to Washington University. A year later, the Modern Graphic History Library was born.

“Really, Al Parker was the reason the Modern Graphic History Library came about,” Skye says. “Since he was an alum, it was basically based on him and other artists from that similar period.”

The collection gives great insight to how Parker and artists like him worked. He would have photos taken in his studio, and then, using a lucigraph, he would trace the photos and put his own spin on them.

“A lot of illustrators didn’t like people knowing that that’s the way they did it, but they were under such time constraints and deadlines that it was impossible to do without,” Skye says.

Related Posts

7 Missouri Waterfalls

A haven for gorgeous scenery, the Ozarks is brimming with stunning waterfalls. April and May are great months to enjoy our waterfalls, as water flow is at its peak from spring showers.

Paddling 340 Miles on the Missouri River

From August 8 to 11, 450 crazy people will paddle down the Missouri River in canoes, in kayaks, and stand-up paddleboats—all competing against each other and themselves in the MR340 race.

Our 3 Favorite Horse Trails in Missouri

The Ozarks and Missouri River wilderness regions are particularly captivating. One of the best ways to experience hidden bluffs, elusive creeks, and historic cabins is by horseback.