This article is presented in partnership with Missouri Meerschaum.

Corn cob pipes got their start right here in the Show-Me State thanks to Missouri Meerschaum Company. Founder Henry Tibbe, a Dutch immigrant and woodworker, began creating the pipes in the 1860s in Washington, Missouri, which is now fondly known as the “Corn Cob Pipe Capital of the World.” Now the company is celebrating its 150th anniversary at the same place it began.

U.S. Gen. Douglas MacArthur was rarely seen without his beloved corn cob pipe, and the commander’s namesake, “MacArthur 5-Star Corn Cob Pipe,” remains a popular purchase from the company.

Have you ever wondered what makes these pipes so special? Or why they are known as the smoothest pipe? Or perhaps, how Missouri Meerschaum creates them?

Well, we have all of the answers for you. For the most part, the corn cob pipes are still made the same way they were over 100 years ago.

You, of course, can’t have corn cob pipes without growing and harvesting the corn first. Back in the 1860s, when Missouri Meerschaum began, cobs from any field were collected and used. But because of years of hybridization, smaller cobs are now produced. As a result, the company commissioned the University of Missouri to develop a corn seed that produces a bigger cob. Today, Missouri Meerschaum owns around 150 acres of Missouri farmland where the corn is grown for the pipes.

After the cobs are collected, they are stored in outdoor bins until they can be shelled. A vintage sheller has to be used because today’s newer equipment is designed to break up cobs instead of removing the kernels. After shelling, the cobs are stored on the third floor of the factory for two whole years. The aging process is important because it makes the cobs harder and dryer.

After two years in storage, they are sawed into pipe lengths and sorted by size. Then each is turned on a lathe, a machine for shaping wood. The MacArthur and the Country Gentleman, a couple of the most popular pipes at Missouri Meerschaum Company, are hand-turned on the lathe. The tobacco holes are then bored into the bowls and they are sent to one of the several turning machines. Each machine produces a unique shape.

Then the “filling” process begins. A plaster coating, made from a secret, patented recipe, is applied to the surface of the bowl. After they dry, the bowls are sanded until smooth. Less expensive bowls are varnished in a concrete mixer, while more expensive bowls are placed on spindles that rotate through a spray booth where they are coated with lacquer.

The bowls are given time to dry before they are each assembled by hand and wood stems are printed with ink so they still appear cob-like. After the tedious process, the pipes are ready to be packaged and shipped around the world. Approximately 5,000 pipes are shipped daily from Missouri Meerschaum with no signs of slowing down in the future.

Related Posts

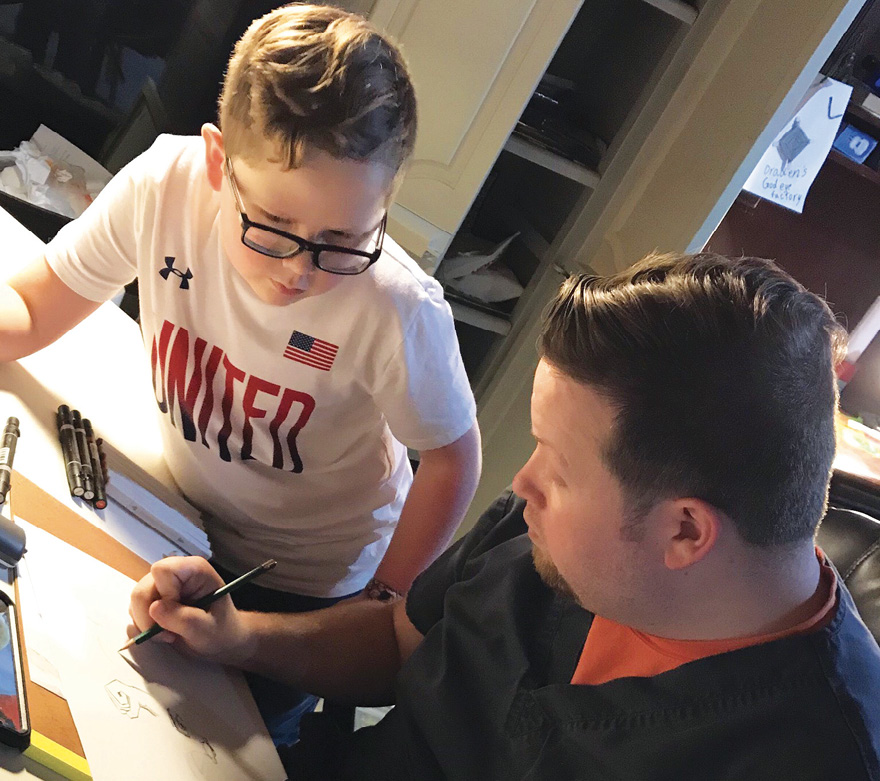

A Farmington Artist Passes His Craft Through Generations

Farmington artist Brandon Warren teaches his son that good artists can make art anywhere and with whatever supplies are available.

The Story Behind General Douglas MacArthur’s Legendary Missouri-Made Pipe

Here's how the Missouri Meerschaum company ended up being commissioned to create a custom pipe for one of America's most legendary generals.

This Fulton Paper Goods Company is Making Waves Nationwide

Today, gifts and stationery created by this Fulton-based company appear on the shelves of fine boutiques nationwide and at major retailers including Anthropologie and Paper Source.