We thought they were gone, but it turns out there were just hiding. Over the past twenty years or so, Missouri’s black bears have been making a major comeback. See where they’ve been spotted and learn all about our good-news bears.

Photo courtesy of the Missouri Department of Conservation

Photo courtesy of Matt Miles

Robert’s house is 35 miles north of the bear’s breeding range boundary in Park Hills. Lisa Pini lives even farther away, in the St. Louis suburb of Ballwin. Last year, she saw a bear in her backyard. Unlike Robert’s bear—which was “150 pounds tops,” he says—Lisa’s visitor was a big one, napping on some indigenous plants just behind her door. The bear got sleepy. Ballwin got ruffled. The town’s police department had to issue a notice on Facebook, and Tom Meister, wildlife-damage biologist for the Missouri Department of Conservation (MDC) had to deal with “probably 100 different pictures” of scat sent in by Ballwinites hoping they’d found traces of the bear.

“I was excited,” Lisa says. “How often do you see a bear in the city?”

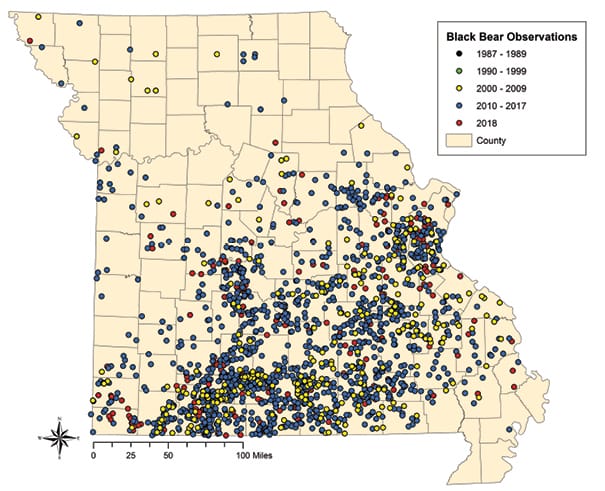

In recent years, black bears have expanded north, all the way to backyards in Imperial and farther northwest on the other side of the Missouri River, where they’ve been spotted in New Florence. On the other side of the state, Missourians have reported bear sightings from Lebanon, Missouri, to Calhoun in Henry County, 100 miles to the north. That’s a significant distance, given that the black bear’s official range ends about 100 miles from the Arkansas line, generally below Interstate 44. Any farther north and the unbroken forest gives way to cities and agricultural land.

The bear is back, but that doesn’t mean it’s everywhere. The most recent estimate, based on a 2012 population projection from the MDC, says there are 350 here. That’s a lot more than the estimated zero bears believed to inhabit the state 80 years ago.

Photo courtesy of Matt Miles

Hiding Out

In 1811, John Shaw’s contribution to the pioneering business was the finding that he could squeeze 800 gallons of bear oil from 300 bears. In 1818, Henry Rowe Schoolcraft—when he wasn’t chasing them on foot—marveled at the number of bears he witnessed in his famous trek across the Ozarks. In traditional pioneer fashion, Shaw and fellow muzzle-loading entrepreneurs nearly wiped out the Missouri black bear population within 80 years.

High bag numbers combined with logging and homestead clearing in the Ozarks and the Ouachita Mountains in Arkansas stressed black bears to their limit. Timber clearing in the Ozarks ramped up dramatically in the 1880s, and by 1890, an animal hardy enough to survive in the Alaskan subarctic and the Floridian subtropics was believed to be extinct in Missouri outside the Bootheel. In the low, remote swamplands of southeast Missouri, they held on into the 1920s, until the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927 killed 500 Americans and took the rest of the Bootheel bears downriver.

So the black bear was gone—sort of. Eventually, Minnesota bears trucked into Arkansas in the 1950s and ’60s by the Arkansas Game and Fish Commission started wandering north into Missouri. In the ’50s, Missourians shot and killed all five bears reported in the state. But still they came.

In 1991, a DNA study of Missouri bears revealed a surprise: some of those Arkansas bears had bred with remnant Missouri bears, who had apparently Bigfooted around out of sight in small numbers all this time. Healthy habitat and protections for bears have led to their modern resurgence.

Arkansas bears are considerably further along in their resurgence. The Natural State has 5,000 black bears, and hunters there take more black bears each year than the total number of bears living in Missouri. When the bear population here breaches 500, the state will consider hosting a hunting season here, too, says MDC bear biologist Laura Conlee.

Bear reintroduction in the Ozark Plateau, especially in Arkansas, is considered one of the most successful large carnivore reintroductions in the world. And it’s not just us: black bears are on the rise across the entire country, with numbers more than doubling this past half century.

Backyard Visitors

That’s why Robert Piva and Lisa Pini saw bears in their backyards. What the state conservation department describes as the black bear’s range stops well short of St. Louis. But male teenagers are curious mammals, and once a bear leaves the den, it sometimes goes on a 60-mile walkabout, exploring new territories to call its own. Females, on the other hand, tend to stay relatively close, spreading in “rose petal” fashion, Laura says, meaning the actual breeding range of bears expands slowly. If you live in Osage Beach or Hermann and you see a bear, it’s probably a male.

“Those areas present a particular challenge for us, given that they tend to have a higher human population density,” Laura says. “Folks in these areas haven’t lived with bears in their lifetime.”

Most people seem to support the black bear, though. Even in Ballwin, site of the 2018 drama, there was “more excitement than worry,” says Ballwin police officer Scott Stephens.

Among large carnivores, black bears don’t incite the kind of histrionics that gray wolves provoke with ranchers in New Mexico. The bears do minimal damage to developed land, Lisa Pini’s wild strawberries notwithstanding. And unlike the fat, heavy grizzly bear, black bears are excellent tree climbers, wildlife officials note; in a pinch, they tend toward flight rather than fight.

There has been exactly one bear death in recorded history in Missouri. In 1969, Russell Ringer entered the cage of a 750-pound Eurasian brown bear. The bear was stuffed into a cage so small it couldn’t stand up. Ringer had decided that if he was going to wrestle the bear later when the carnival opened for the soldiers in Fort Leonard Wood, he’d better muzzle it first. “When we got there, it was jumping up and down on him in the cage,” carnival owner Del Rohr told The Kansas City Times. “I think he was dead before we got him to the post hospital.”

That is unlikely to happen to you, wildlife officials say.

Greg Combs, regional director for the Missouri Department of Natural Resources’ eastern region, says the agency has proactively begun buying bear-proof dumpsters for state parks in areas where bears have been sighted, such as at Johnson’s Shut-Ins and Sam A. Baker State Parks. But most of the agency’s work is about educating the public. “We’ve not encountered any aggressive bear situations whatsoever, knock on wood,” he says.

Bear Bait

When scat hits the fan, Tom Meister is the last line of defense. As the state’s resident wildlife-damage biologist, Tom has flown to New Jersey to learn how to trap bears and to the Black Hills of South Dakota to learn how to trap mountain lions. Tom usually works with landowners who file animal nuisance complaints, but occasionally he gets dispatched for the fun stuff.

If the bears won’t leave after being harassed, then the trap will be the last choice, he says. “I’ve caught several bears through the years.”

Bears don’t always go easily. They’re highly intelligent mammals with an excellent memory. “On the East Coast, bears in suburban areas learned over time that if they didn’t destroy the bird feeder, it got refilled,” MDC’s Laura Conlee says. She describes bears that learned what day trash pickup was, visiting curbsides that morning.

Bears’ acute memories can make them difficult to wrangle. Tom encountered such a bear outside Warrenton before coming up with a trump card.

Photo courtesy of the Missouri Department of Conservation

“I got some glazed doughnuts from Kroger,” he says, chuckling. “He’d been caught before. He knew the routine. He was apprehensive about going back in that trap, but he just couldn’t resist the doughnuts.” Doughnuts, sardines, or liquid smoke, anything with a strong scent, can attract a bear.

Bear biology

Doughnuts make up a relatively small percentage of a wild black bear’s diet, but research shows black bears are eclectic eaters. Here is what an Arkansas state employee who analyzed bear guts found in those stomachs: one-third acorns, one-fifth pokeweed berries, one-tenth hickory nuts, one-tenth domestic pig, and the rest composed variously of persimmons, “walkingstick” insects, grapes, bee larvae (note: Winnie the Pooh was not as interested in honey as he was in bee babies), grass, and white-tailed deer.

Black bear mothers give birth to litters of two, three, or four cubs and keep them around for a year and a half, after which they breed again. Even mothers with cubs prefer to saunter off or climb trees when confronted by humans, Laura says. As long as you’re not feeding them or trying to pet them, you should be fine, she adds.

And if you’re worried about confusing black bears with the larger, western brown bears, here’s a simple identification tip: If it’s in Missouri, it’s a black bear. There are no grizzlies here.

A bear’s sense of hearing is as good as its eyesight is bad, so if you happen to see one on the trail, clapping and singing is a good way to alert it to your presence without startling it. Even a mother with cubs will generally flee, unless you get between them.

Feature image courtesy of Matt Miles

Article originally published in the June 2019 issue of Missouri Life.