This article was originally published in our July/August 2021 issue.

Anyone who has watched Hollywood westerns would recognize the scene. Two men stand facing each other in the empty dirt street, each primed to draw and fire his weapon at the other. Inevitably, the hero allows his opponent to make the first move, whereupon he launches a single fatal bullet at his foe. Fade to black, as the morality play ends.

In the brief history of what we refer to as the Wild West, it hardly ever happened that way. It stood to reason that if a man hated another sufficiently to wish him dead, the last thing he would do would be to give his opponent an even chance. Hence, most of the West’s famous pistol fighters—Jesse James, Billy the Kid, and John Wesley Hardin, to name a few—were shot in the back, or from ambushes. The face-to-face stand-up gunfight was largely an invention of the movies.

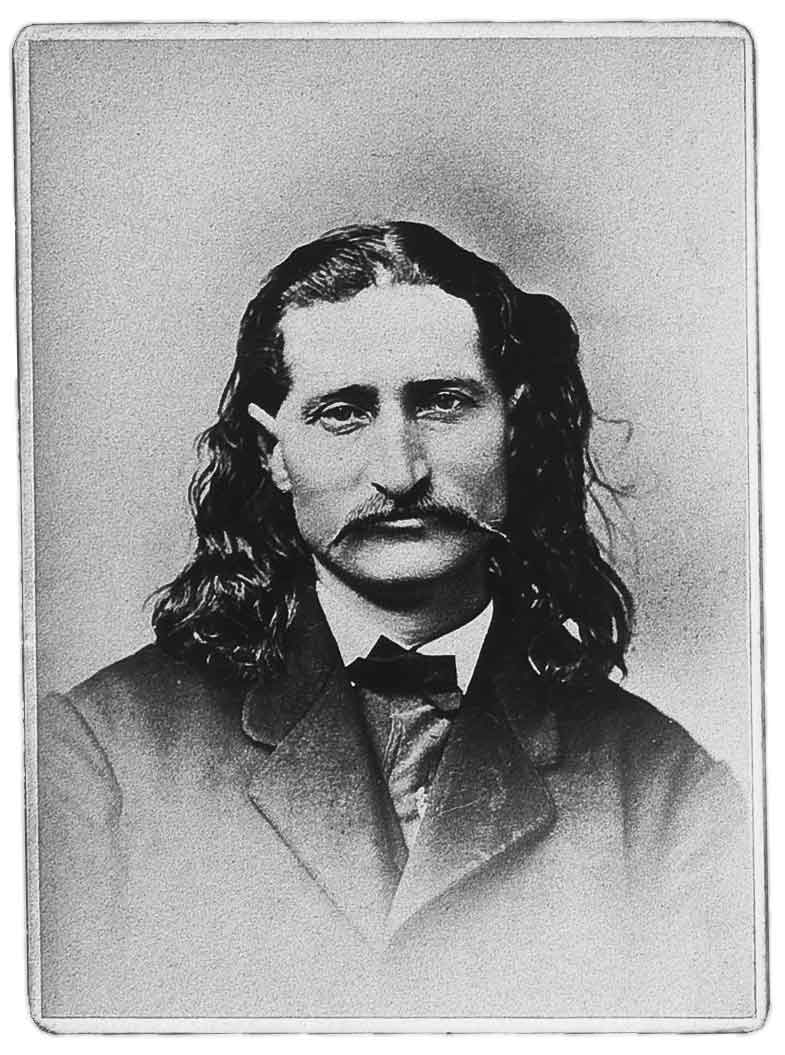

There was, however, an actual historic confrontation that set the tone for all future cinematic face-downs. It featured the redoubtable James Butler Hickok, best known to history and lore by his sobriquet, “Wild Bill.” The fight took place in Springfield, Missouri, on the morning of July 21, 1865, between Hickok and a local gambler named Davis “Little Dave” Tutt.

By this time, Hickok was no stranger to violence. He had served the Union Army in various capacities during the entire four years of the Civil War. And just prior to enlisting, the twenty-one-year-old Hickok had been involved in a fight that left three men dead and still arouses controversy among western historians.

It occurred in Nebraska Territory, in 1861. Hickok was working as a stock tender at the Rock Creek Pony Express relay station, on land that had previously belonged to a local named David McCanles. On July 12, McCanles, his son, and two others—all allegedly unarmed—showed up demanding either payment of the balance of the sale price or the return of the property. An argument ensued, and when the smoke cleared, all but McCanles’s young son lay dead. Hickok was apparently responsible for at least one of the killings.

As Hickok later told it, McCanles was the “captain of a gang of desperadoes, horse thieves, murderers, regular cutthroats,” and the “terror of the border.” Armed with only a rifle, six-shooter, and knife, he managed to slay all ten gang members, but at a terrible cost: “There were eleven buckshot in me. … I was cut in thirteen places, all of them bad enough to have let out the life of a man.”

Hickok’s account was pure nonsense, but a gullible reporter from Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, presumably after interviewing the shootist himself, wrote a blood-and-thunder tale that was faithful to Hickok’s version and did much to spark what would become the legend of Wild Bill.

When the war ended in early 1865, Hickok was one of a large number of veterans who suddenly found themselves out of uniform and without prospects. He drifted to Springfield, where he turned to gambling, a pursuit that he would follow for the rest of his life. According to Hickok biographer Joseph G. Rosa, “He became a well-known figure on the streets of Springfield. … He and his companion, Davis Tutt, were a familiar sight, each armed with two revolvers.”

It was an unlikely friendship; Hickok had served as scout, courier, and according to some accounts, spy for the North, while Tutt had fought for the Confederacy. On the night of July 20, the two were playing cards—and no doubt, drinking—when a disagreement arose between them over the amount of money Hickok owed Tutt. The difference was ten dollars. To settle the question, Tutt simply took his friend’s prized Waltham gold watch as collateral. Ever sensitive to popular opinion and fiercely protective of his image, Hickok warned Tutt not to wear the watch in public.

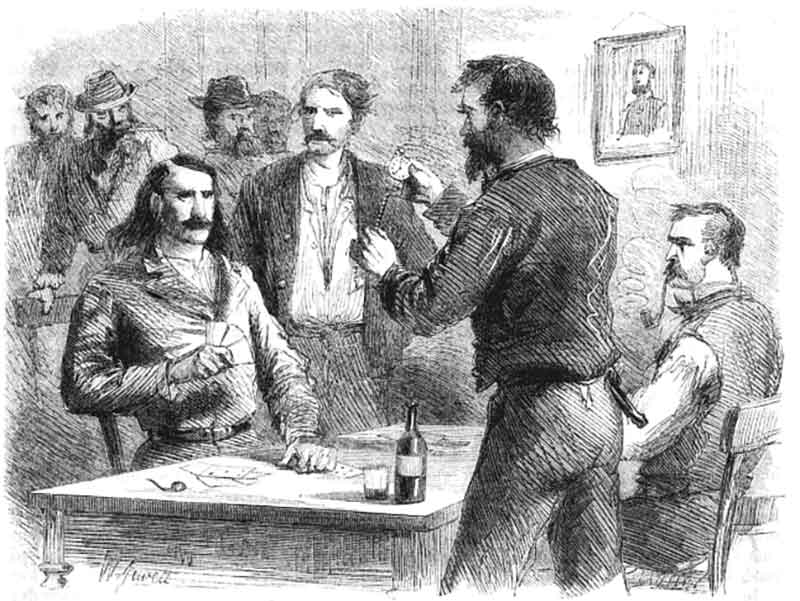

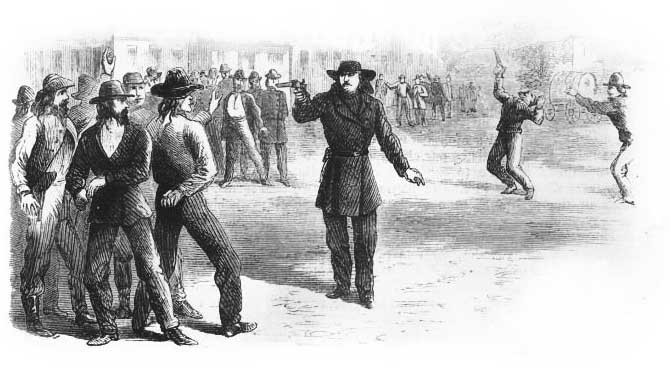

Next morning, Hickok met his erstwhile friend in the city square and found him conspicuously sporting the timepiece. After an unsuccessful attempt to resolve the rift, the two went their separate ways. Around six o’clock that evening, the two again saw each other on the square. According to various sources, Hickok said, “Dave, here I am,” whereupon both men assumed a duelist’s stance, turning sideways to offer the smallest possible target.

Facing each other at a distance of around seventy-five yards, both men fired, in practically the same instant. Some witnesses later swore to hearing only a single shot. Tutt’s shot went wide, while Hickok, with calm deliberation, had laid his right arm across his left to steady his aim before firing. His ball, according to the subsequent coroner’s report, “entered on [Tutt’s] right side between the 5th and 7th rib and passed out on the left between the 5th & 7th rib.” The wound was almost immediately fatal. “From his sudden death,” wrote the coroner, “I am led to believe that some of the large blood vessels were wounded.” The stricken Tutt reeled, ran from the square, then back again, and after reportedly calling out to his friends, “Boys, I am killed,” fell dead.

From a technical standpoint, Hickok’s was a nearly impossible shot, considering the distance between the antagonists and the nature of the relatively primitive handguns of the period. Hickok favored the model 1851 Colt .36-caliber cap-and-ball Navy revolver, and carried a brace of them throughout his career, even after more efficient weapons had rendered them obsolete. He often staged shooting demonstrations, and by all reports, he was an extraordinary marksman, combining accuracy with an amazing sang-froid.

Hollywood notwithstanding, Old West gunfighters did not simply ride off into the sunset after felling someone in a shootout. Although the quality of law enforcement varied from town to town, it was customary for the survivors to face charges, which might range from simple assault to murder. After dispatching Dave Tutt, Wild Bill was called upon to answer for his role in the fight. He was initially charged with murder, but the charge was subsequently reduced to manslaughter.

Hickok’s trial lasted three days. He was represented by John S. Phelps, the former military governor of Arkansas. Interestingly, the court spelled Hickok’s name in various ways (“the State of Missouri vs. James Haycocke” and “William Hickok has been indicted”) before finally getting it right. Clearly, he was not yet the Wild Bill of legend, although his duel with Tutt would further propel him into national prominence.

While there was controversy over who had fired first, the jury determined that the killing was justified, since Tutt had provoked the fight by deliberately flaunting Hickok’s watch. Given the often whimsical nature of Old West justice, the verdict was not all that unusual. As stated on the city of Springfield government site, “Nothing better described the times than the fact that dangling a watch held as security for a poker debt was widely regarded as a justifiable provocation for resorting to firearms.”

As with most dramatic events in the Old West, oral history aided by sensationalist newspaper reporting was responsible for a number of often outlandish interpretations as to what actually occurred. As a result, there are several versions of the fight itself, just as there are various iterations as to its cause. In some versions, the falling out between Hickok and Tutt occurred after Wild Bill seduced and impregnated Tutt’s sister. A more common tale has Tutt stealing the affections of a fallen angel of whom Hickok was especially fond. These embellishments are almost certainly apocryphal, as were the “recollections” of those who, decades later, claimed to have witnessed the fight. In many if not most of these cases, the “witness” had not yet been born when the two gamblers shot it out in the Springfield street.

One dramatic tag-on to the fight has Hickok wheeling around after firing the fatal shot, to confront a gang of Tutt’s angry friends. With both pistols drawn, Hickok warns them that any hostile movement on their part would be met with lethal force. Actually, there is a fairly high probability that this actually happened. By the time the fight occurred, a large number of Springfield’s citizens had turned out to watch, anticipating bloodshed. Tutt’s rough-hewn friends had reportedly teased Hickok mercilessly about the loss of his watch, and it is possible that at least some of them were among the crowd.

The city of Springfield has gone to great lengths to preserve the details of the Hickok-Tutt showdown for the visiting public. It has placed markers indicating where each man stood and a plaque that describes the fight in detail. Although a number of witnesses were called during the trial, the actual transcripts were lost in a fire; nonetheless, the surviving coroner’s report provides the gist of their testimonies. The city’s combined Public Works and Public Information departments have subsequently created an audio tour, marking where each of the witnesses stood and what they observed. Actors provide the voice-over.

Hickok would go on to pursue a checkered career in law enforcement, all the while spending his off-hours at the gaming tables. Ironically, just eleven years after his duel with Davis Tutt, Wild Bill Hickok met his end in the same manner as so many other notorious shootists; he was shot in the back of the head while playing poker in a Deadwood, Dakota Territory, saloon. His assassin apparently had better sense than to face the so-called “Prince of Pistoleers” in a face-to-face gunfight, although the killer would eventually hang for the deed. The recently married Hickok had had a premonition of his own demise, writing months earlier in a letter to his wife, “Darling, if such should be we never meet again, while firing my last shot, I will gently breathe the name of my wife Agnes.”

Header photo // ©Wild Bill Hickok vs Dave Tutt by Andy Thomas

Related Posts

Bellefontaine’s Beautiful Death

The Mourning Society of St. Louis allows people to journey back and see how the deceased were honored differently in the past. Bellefontaine Cemetery And Arboretum is the perfect example of the 1800s movement to create rural cemeteries for mourners.

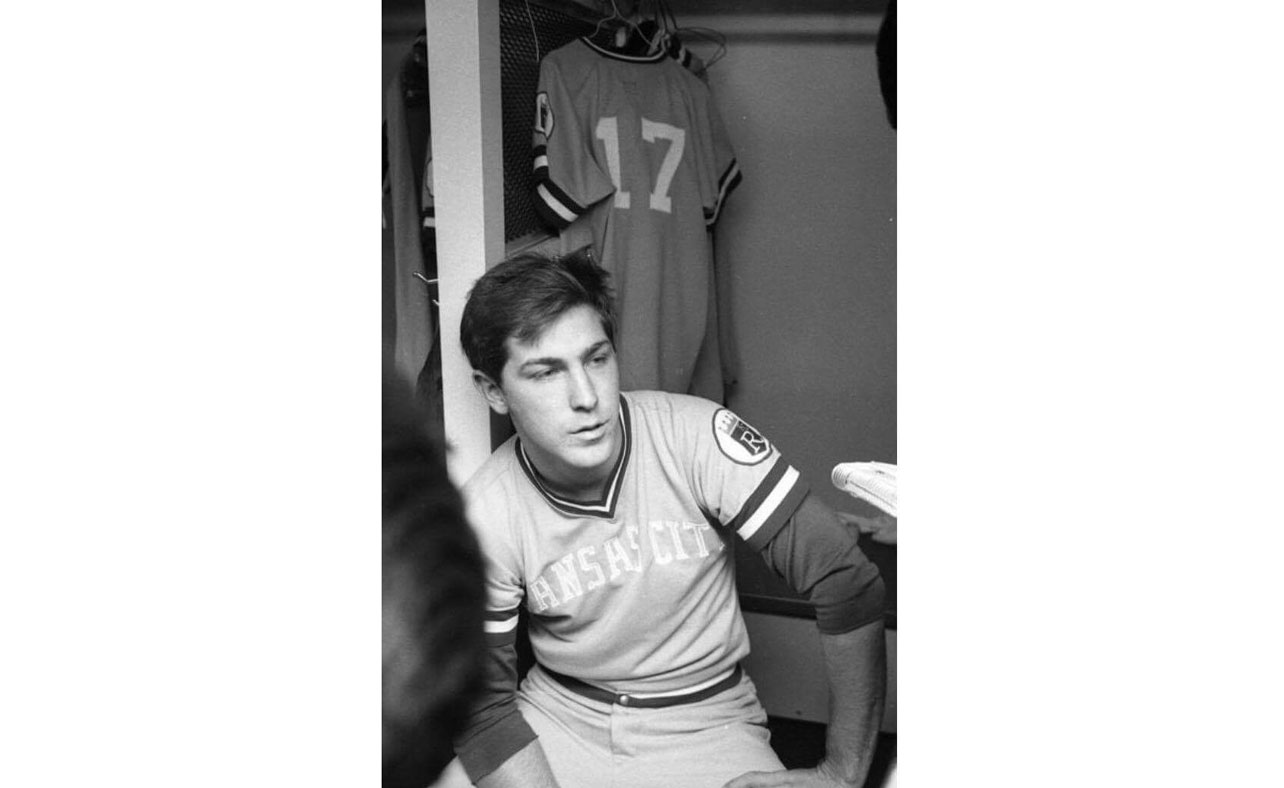

Mark Littell Shares His Wildest Stories

Country Boy is Mark’s second book, following his 2016 memoir, On the Eighth Day, God Made Baseball. Mark, who used to enter games to John Denver’s “Thank God I’m a Country Boy,” describes his latest work as a coming-of-age nonfiction story about how his character formed while growing up in Missouri.

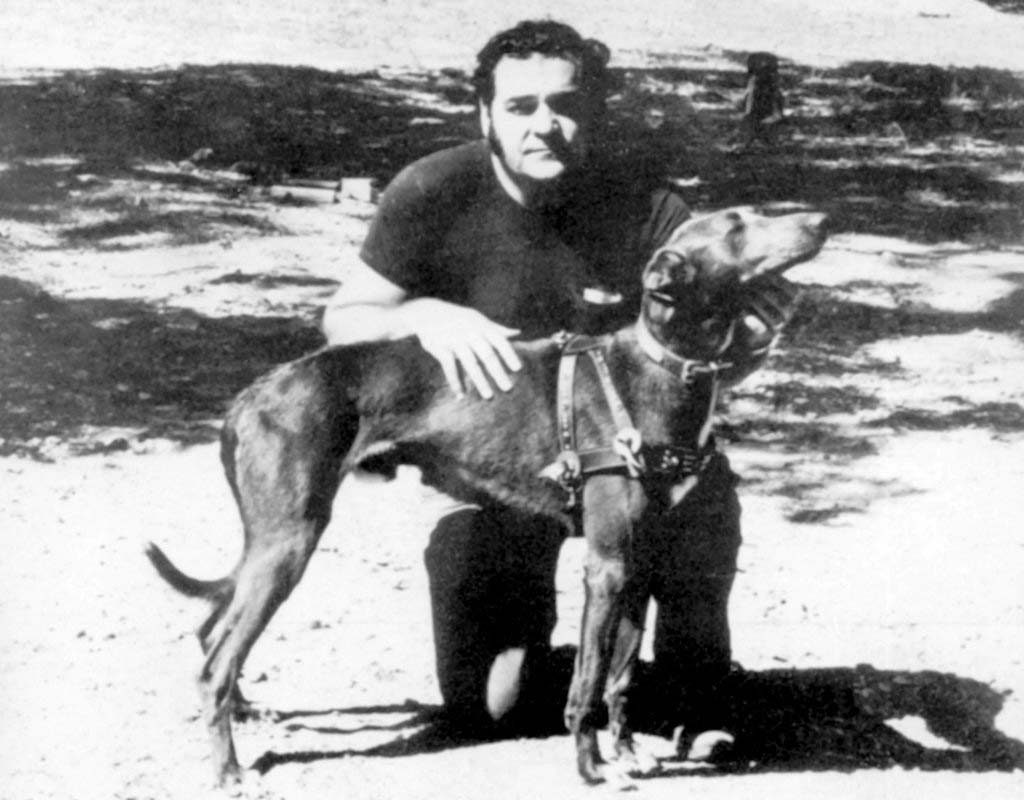

Skidmore Revisited Part 1: The Death of Ken McElroy

Ken had a drink at the bar, left, started his truck, and lit a cigarette. And then someone shot him in the head, in broad daylight, before 45 witnesses, with Trena at his side. After decades of terror, the bully was finally gone.