This story originally appeared in the October/November 2014 issue of Missouri Life magazine.

August 4, 1900, dawned bright and clear as some one thousand locals gathered for a midsummer picnic in the St. Francois County mining community of Doe Run. The event featured carnival rides, barbecues, and liquor concessions and was attended by most of the families in the area. Some were seeking relief from the August heat at the lemonade stands or strolling along the river, while others lazed in the shade of the trees or rode the steampowered swing—a type of carousel, sporting gaily painted horses.

According to local lore, handsome Frank Harris had unwisely bought steam swing tickets for Ollie Swinford Dooley, the pretty seventeen-year-old wife of Les Dooley. Soon, Les approached with a handful of his own tickets. When he ordered Ollie to ride the swing with him, she reportedly pointed to Harris, who was boldly leaning against her swing, and replied, “I care more for the little finger of Frank Harris than for your whole body.”

Within the span of five minutes, this ill-considered remark sparked the wanton killing of two men, the fatal shooting of a third, and the wounding of several others, including a young girl. As the St. Louis News Dispatch of the day colorfully phrased it, “[O]ver all [hung] the pall of firearm smoke and the ghastly consciousness of sudden and violent death.”

It makes for a good story. Although the shootout at the Doe Run picnic did occur and was indeed a bloody affair, the causes of the conflict are considerably murkier, go back much further, and have little if anything to do with a carnival-ride flirtation.

It is a remarkable aspect of many feuds that the reasons for the violence are often lost in the haze of the past—fictionalized, glorified, or simply forgotten. Even the famous war between the Hatfield and McCoy clans of the Kentucky-West Virginia border country stemmed from causes that are still disputed. As time passed, feuding families rarely felt the need to hearken back to the feud’s origins to justify their actions.

‘Alleged Facts’

Feuds between extended families are an American tradition. The noted Texas gunfighter John Wesley Hardin took time away from his desperate deeds of murder and mayhem to side with one of the factions in the bloody Sutton-Taylor Feud of the late 1800s. Some thirty-five men died in a pointless slaughter that not even the famed Texas Rangers could curtail. The Graham-Tewksbury Feud— known throughout Arizona’s Tonto Basin as the Pleasant Valley War—was a classic Western dustup over sheep and cattle.

As for Missouri, our most dysfunctional and bloody inter-familial conflict has come to be known as the Dooley-Harris Feud.

Many of the details have been lost, as participants and observers died off or moved away with the passage of time. Indeed, the Farmington Times, the local newspaper that reported the Doe Run shootings, stated on August 9, 1900, “It appears that there was a sort of feud between the two families, the beginnings of which are not clear, several different stories as to the cause being afloat.”

Apparently, after the publication of this issue, some of the locals weighed in with their own versions of the feud’s origins because, two weeks later, the same paper printed a column outlining the “History of Alleged Facts.” According to this account, the trouble had begun over a year earlier, when sixty-four-year-old farmer William Dooley Sr. heard a nocturnal disturbance at his corn crib. Upon investigation, he could make out a figure illicitly filling his sack with Dooley corn. Raising his Winchester, Dooley fired, hitting the thief, who managed to escape. A short time later, Henry Harris, patriarch of the neighboring clan, died, ostensibly of a bullet wound. Although there was no way to prove their suspicions, the Dooleys always assumed that old Henry was the corn thief.

The Harris clan—comprised mainly of the late Henry’s four sons, Jim, Frank, Wes, and Bill—took no action at the time. However, within the year, Jim Harris bought the farm that the Dooleys rented, where they lived and worked, and ordered them to immediately vacate the property. Dooley, who had a crop in and had always assumed that his lease extended until the end of the harvest season, protested. He took the Harrises to court, but the judge upheld the eviction, and the Dooleys were forced off the farm.

The Dooleys—Old Bill Sr. and his four sons, John, Bill Jr., Les, and Joe—were understandably bitter, having been driven from their home before they could harvest their crops. The Harrises were unmoved by the Dooleys’ plight. Soon, bad things began to devil the Harris family. Their stock and dogs were poisoned, and although local law enforcement never pressed charges nor arrested any suspects, the Harris boys harbored little doubt as to who was behind the killing of their animals.

Circumstances continued to throw the two clans into each other’s path. In order to make a living, John Dooley took a job teaching in the same school that the Harris children attended. Apparently, Dooley was so liberal with his use of the birch switch in disciplining the fledgling Harrises that criminal charges were filed against him. Not surprisingly, the enmity between the two families grew apace.

‘I Will Whip Them All’

Picnics were the main summer venue in this part of Missouri. They afforded the hardworking locals—miners, farmers, businessmen, their wives, and their children— the opportunity to spend a few relaxing hours, share a drink with friends and neighbors, and generally enjoy a lazy Sunday. On July 25, 1900—just two weeks before the Doe Run affair—a picnic was held at Flat River.

Members of both the Dooley and Harris families attended the picnic, and it took little provocation for a fight to break out between the two factions. No weapons were in evidence, although some accounts mention the use of brass knuckles, but the young men parted, if anything, even angrier than before.

By the day of the Doe Run picnic, both sides were resolved to settle their differences with violence. However, while the Harris brothers were anticipating a fistfight, the Dooleys arrived carrying firearms. Although two witnesses later testified at the inquest that they later saw all four Harris men firing, it was determined beyond doubt that Wes was the only Harris who was armed.

William Dooley Sr. and his four sons arrived at the picnic at around 8:30 in the morning. Significantly, they had left their women at home. All carried pistols and a healthy store of ammunition and had stowed Winchester rifles under the hay in their wagon. According to the inquest testimony, the Harris boys arrived an hour or so later, along with their widowed mother, Jim’s wife, and seven children. Frank Harris attended the picnic with Ollie Swinford Dooley, Les Dooley’s estranged wife.

There are at least two versions, all sworn to by eyewitnesses, as to what happened next.

According to one account, it was the Harrises who drew first blood. Wes Harris approached the elder William Dooley, and without preamble, pushed him. Wes then drew his pistol and shot the old man in the hip. The bullet severed an artery, and Dooley bled out in minutes.

Another iteration, however, has the old man advancing on Wes with a club and beginning to draw his pistol, whereupon Wes drew his own weapon and shot the old man down. It is safe to assume that, whether provoked or not, Wes shot Bill Sr., and after the old man fell, Wes shot young John Dooley, whereupon the firing became general.

Wes was the first Harris to fall, shot several times by rifles in the hands of Les Dooley and his wounded brother, John. Wes was, in the words of the newspaper report, “literally shot to pieces.” According to one witness’s statement, his last words before the shooting began were, “I’m not afraid of your guns.” Wes’s mother, Amanda “Grandma” Harris, later testified, “A man came up to me and told me that one of my boys was killed. It was Wes; he breathed about three times after I got to him and died.”

Within the next few minutes, Joe Dooley shot Frank Harris, seriously wounding him, while Bill Dooley Jr. turned his gun on Jim Harris, shooting him twice in the back. Just a few minutes earlier, the unarmed Jim had shouted to no one in particular, “If you will take their guns away from them, I will whip them all!” Frank and Jim, though grievously wounded, would survive.

When Jim’s wife saw her husband fall, she shouted in desperation at young Bill Dooley, “For God’s sake, quit!” He fired on her as well but missed.

Bill Harris, arriving late at the picnic, was warned of the mayhem taking place and managed to escape. Meanwhile, as Wes’s grieving mother knelt fanning the flies from her son’s bloody face, an enraged Bill Dooley walked up to the dead man and shouted, “God damn you!” before picking up Wes’s revolver, shooting him twice more, and then kicking him in the head. Stunned at the abuse her dead son was taking, Wes’s mother brought her parasol down on Dooley’s head. He cursed the distraught old woman and, pointing his pistol at her, stalked off muttering, “He killed my father, and I allow to kill the rest of them before I stop!”

With no more Harrises to shoot, the Dooleys ceased fire. Moments later, a stunned silence settled over the picnic grounds. Throughout the altercation, bullets had flown in all directions, one of them wounding a sixteen-year-old girl in the ankle. Miraculously, no one else among the hundreds of people attending the picnic was hurt.

‘Now I’ve Got You’

Because there was no formal law in the 1,500-person mining town of Doe Run, the Dooley brothers, after strutting around town for the rest of the day, surrendered to the Farmington sheriff. In the process, they turned over a Winchester rifle and four pistols; one of them the former property of Wes Harris. Indictments were brought against Joe, Les, and Bill Dooley for Wes’s murder, with bail set at $8,000 each. Not surprisingly, the finding of the inquest, according to the Farmington Times, was that “W.H. Dooley came to his death at the hands of the Harris boys and that Wes Harris came to his death at the hands of the Dooley boys.”

As Frank Harris recovered from his wounds, he reflected, “I reckon it’s well enough that we didn’t have our guns, for if we had ’em, we would now probably be where the three Dooley boys are, boarding with Sheriff Jeff Highley. We got shot up considerable, but I reckon that beats being in jail with a murder trial hanging over us.”

If Frank was anticipating death sentences or lengthy jail terms for the killers of his brother, he was in for a disappointment. As it turned out, lawyers for Les and Joe Dooley managed to get their clients continuance after continuance, and on July 16, 1905, a jury found them not guilty of murder.

A different fate awaited their brother. Nearly three years earlier, Bill Dooley boarded a Mississippi River and Bonne Terre train, walked up behind an unsuspecting Bill Harris, and, with the words, “You killed my father, and now I’ve got you!” pumped three bullets into the back of Harris’s head, killing him instantly. In fact, Bill Harris had not participated in the fight at all; ironically, he had escaped the Doe Run bloodbath unharmed, only to fall victim to it two years later. Bill Dooley was judged to be incurably insane and was committed for life to the Disturbed Ward of Missouri’s State Hospital No. 4. After a brief escape, he was recaptured and confined there until his death from tuberculosis in June 1907.

It took a grievously wounded John Dooley nearly two years to die after having been shot by Wes Harris at the picnic, but die he did in January 1902. The two surviving Harris brothers, Frank and Jim, were involved in several shooting scrapes in the years following the Doe Run incident. Apparently, none of the gunfights related to the feud. After serving time for shooting a man to death, Frank Harris died of tuberculosis at brother Jim’s home in April 1909. Two years earlier, Jim had suffered a near-fatal gunshot wound in his second gunfight since Doe Run. He survived, however, to face murder charges for killing a man in the previous shootout.

Apparently, there were no saints on either side of the Dooley-Harris Feud.

Illustrations by Merit Myers

Related Posts

Country-Folk Crooner

Todd Day Wait has performed worldwide and is releasing a new album this year.

January 17, 1927

Birthday of humanitarian Dr. Thomas Dooley in St. Louis. He was a diligent medical pioneer in Southeast Asia and John F. Kennedy named Dooley as his inspiration for starting the Peace Corps.

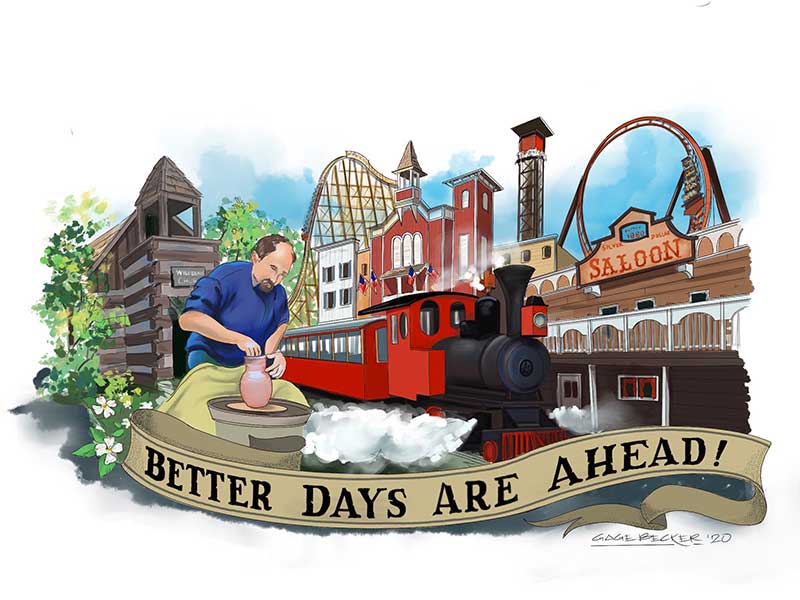

Ozarks Inspiration

Young artist turns mandatory break from classes into a pandemic commission.