This article was originally published in our July/August 2020 issue.

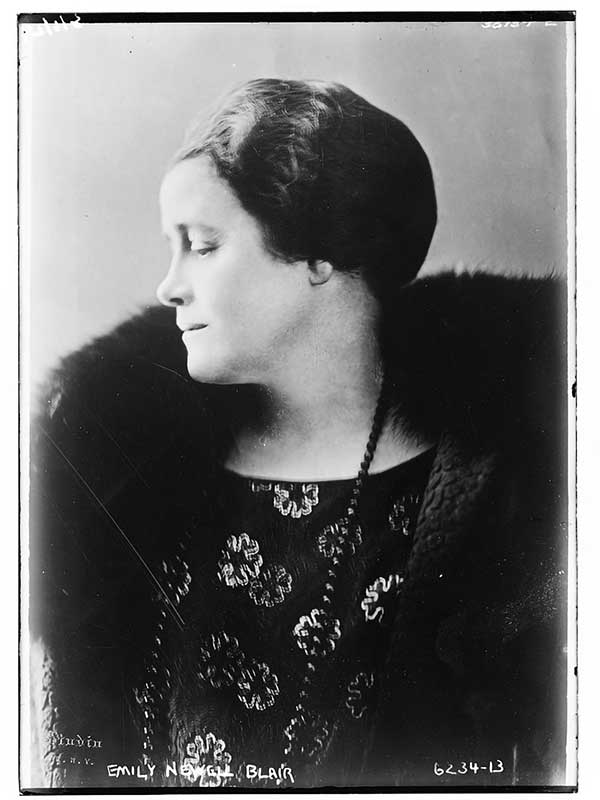

In 1920 when the 19th Amendment granted women the right to vote, Emily Newell Blair had been active for years in local suffrage organizations and was an in-demand speaker throughout Missouri and later on the national stage. She began her adult life as a sheltered, middle-class wife and mother in Carthage and became, through her writing, speaking, and organizing, a national leader in the women’s suffrage movement and the Democratic Party.

Emily Newell was born in 1877 in the lively mining town of Joplin. Her parents were Pennsylvania transplants who had come west to invest in the zinc and lead mines. Her mother described the Joplin of that time as one of rough, uneven streets with plank sidewalks and many saloons and gambling establishments with “men swaggering along with guns on their hips.” After a stray bullet broke a lamp in their home, her family moved sixteen miles away to a more sedate Carthage in 1883.

In Carthage, Emily began public school. She did well in her studies but felt like an outsider at school. At home, however, she was the eldest of six children and took on the role of leader and mentor to her siblings. After graduating from Carthage High School, she attended Goucher College in Baltimore for a year, but her education was cut short by her father’s sudden death.

She returned to Carthage to take care of her younger sisters while her mother and brother worked to keep her father’s mortgage brokerage business running. Emily watched her mother struggle when some men, distrusting that a woman could succeed as a broker, took their business elsewhere. “If this did not turn my mother into a feminist, it was not without its effect on me,” she later wrote.

After a period of mourning, she began to attend parties, teas, and dances with other young adults of Carthage. She thought that conversations with young men at that time were artificial and didn’t enjoy the “silly flattery of the male by feminine depreciation.” One suitor, Harry Blair, a former high school classmate, proposed, and she married him in 1900.

After two years, the couple moved to Washington, DC, so Harry could continue his law studies at George Washington University—formerly known as Columbian University. While Harry completed his law degree, Emily, who was expecting her first child, became familiar with DC, and the city sparked her interest in politics and government. After Harry graduated, the couple returned to Carthage and began their family, with a daughter, Harriet, born in 1903 and a son, Newell, born in 1907.

Soon after, Harry Blair announced his candidacy for circuit judge, and Emily initiated an extensive letter-writing campaign to support him. She wrote letters thanking supporters for their help in the campaign, answering their questions, and organizing volunteers who wanted to help. Her husband, a Democrat, was defeated when Republicans swept the state, but her role gave her some understanding of politics on a local level.

In 1909, Emily’s writing career began when she sold her first story, “Letters of a Contented Wife” to Cosmopolitan in 1910. She followed this successful debut with stories and articles in Harper’s Bazaar, Women’s Home Companion, Lippincott’s Monthly Magazine, and other publications. She wrote every day while managing her home and raising her children. This time spent developing her writing skills laid the groundwork for future articles, speeches, publicity, and policy she would write for the suffrage movement. She wrote, “This was the most fertile period of my life. Before had come the planting of many seeds. During it, they took root.”

Her first speech was in Springfield where she was invited to address a gathering of Missouri writers. There she met poets, journalists, editors, and fiction writers from all over the state. The writers held annual meetings at the University of Missouri every spring and retreats in the Ozarks every fall, and these sessions led to favorable publicity for her writing from other Missouri journalists.

Emily was often asked by other women writers if she was a suffragist. By this time, she had attended some local suffrage meetings, but after researching the history of the movement in the library, her commitment to and involvement in the cause greatly increased. As her passion for women’s rights evolved, so did her interest in social justice, and she joined a campaign to urge men to vote for bonds for a new almshouse to improve conditions for the poor. Speaking on this issue led to other talks about women’s rights, and she became a popular speaker and writer for suffrage in her home state. After the Missouri Suffrage Amendment was defeated in 1914, Emily, undaunted, accepted the position of the first editor of Missouri Woman, a monthly magazine focusing on suffrage issues.

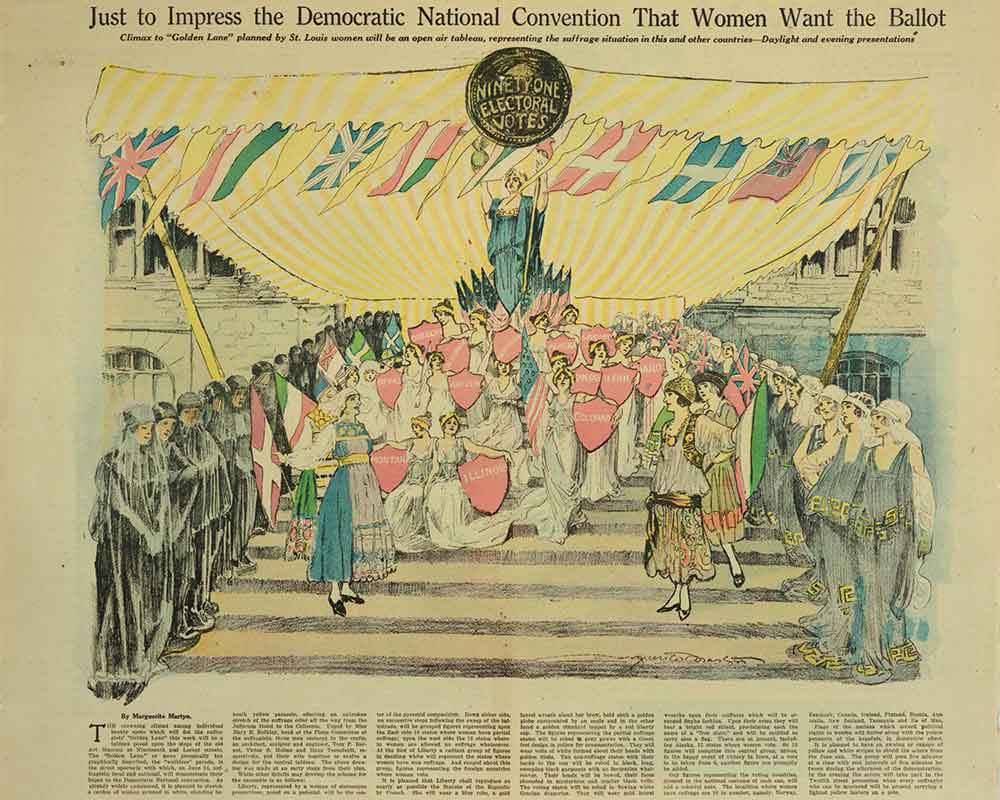

In 1916, the Democratic National Convention was held in St. Louis, and Carrie Chapman Catt, a name known nationally in the suffragist movement, asked Missouri women to devise a demonstration that would urge delegates to consider a suffrage plank in the party platform. Emily’s idea was “a golden lane” of women dressed in white dresses with yellow sashes and parasols to line the streets in complete silence. Thousands of women gathered on Locust Street and quietly watched as men walked to and from the convention. In 1916, there was also a special suffrage convention in Atlantic City, and she attended to hear President Woodrow Wilson speak.

After her extended trip, Emily began dealing with what is still a modern woman’s dilemma. When she returned home, she felt guilty about her long absence and resigned from all her organizations and feminist positions to stay at home full time. She wrote, “Such conflicts are part of the problem of almost every married woman with children who essays extra home activities. The demands of the two are on her to resolve and adjust without failing at home or handicapping her work.” This self-imposed sabbatical lasted one year. In 1917, she accepted a position in the publicity department of the Woman’s Council of Defense and moved to Washington, DC, while her husband served as a YMCA secretary with the 308th Infantry during World War I.

At the Woman’s Council of Defense, she discovered wage inequality when she learned the men working for her earned twice as much money. She wrote articles about this disparity in income and other articles and stories about her experiences as a woman in wartime for women’s magazines. Her principal contribution was writing the book, The Woman’s Committee, United States Council of National Defense, which required months of research and covered women’s war efforts.

In 1919, Emily and her husband returned to Joplin, where Emily resumed her writing career and worked for social causes. The Missouri Equal Suffrage Association became the Missouri League of Women Voters in 1920 when the 19th Amendment was ratified, and Emily was one of the founders. She attended both the League of Women Voters Convention and the State Democratic Convention held in Joplin that year of war victory as well as the Republican National Convention in Chicago and the Democratic National Convention in San Francisco. As Emily and other women conventioneers made their way from Chicago to San Francisco, they stopped in Montana, Washington, and Oregon to hold meetings and give speeches.

In 1921, she was elected Missouri Committeewoman on the Democratic National Committee and moved back to Washington, DC, where she and her husband lived for most of the rest of her life. Later she became the first woman vice-chair of the DNC and held the position for eight years. She put in place more than two thousand Democratic Women’s Clubs across the country where the newly enfranchised women could meet, organize, and learn. Emily and other women party leaders also saw the need for a national meeting place where Democratic women could host social events, hear speakers, and hold educational events. They established the Women’s National Democratic Club in the nation’s capital, and it is still a vital center of Democratic women’s political activities today.

Emily continued to follow both her passions, writing and politics, in the following years. She was the associate editor of Good Housekeeping magazine from 1926 to 1933 where she wrote a monthly book review column. She published two books, The Creation of a Home about interior decoration and A Woman of Courage, a novel. An avid supporter of Franklin Roosevelt, she traveled the country campaigning on his behalf. When he was elected, she advocated for women for positions in his New Deal administration. One of her last appointments was as Chair of the Consumer Advisory Board in 1933. Emily retired in 1944 after she suffered a stroke. She died in 1951 in Alexandria, Virginia. She will be remembered as one of the pioneers of women’s suffrage in Missouri and the entire nation.

Photos // Missouri History Museum, Wikimedia Commons

Additional Credit: telegram crypto groups

Related Posts

September 3, 1923

Cartoonist Mort Walker, creator of Beetle Bailey, and loyal University of Missouri Alum was born on this day. Beetle Bailey’s Camp Swampy was modeled after Missouri’s Camp Crowder where Mort Walker had been stationed.

A Walk Through Missouri’s Largest Municipal Parks

Forest and Swope Park both rank among our nation's largest city parks by acreage, and both played important roles in the development of their communities.

Missouri’s Master of Photo Printing

Miller’s Professional Imaging launches a new brand that pays homage to its past.