Any Farmers’ Market devotee knows to arrive early. Long before the opening bell, shoppers at the Webb City Farmers Market are clustered into tight lines for berries bright as gemstones and towering cartons of okra. The bounty always draws a diverse crowd in this southwest Missouri town: dreamy bohemians with sunflowers cradled in their arms, parents guiding children on leashes, married seniors walking hand-in-hand.

Nothing about the scene stands out—except that on most days, the market’s ethnic diversity represents more than a dozen countries. “I’ve heard people look around and say, ‘I could be anywhere in the world,’ ” says Market Manager Eileen Nichols. Webb City, population 10,000, seems an unlikely place for a Laotian to cross paths with a Mennonite. And yet they do.

At the Webb City Farmers Market, roughly 40 percent of the produce vendors are Hmong. Their presence often raises eyebrows, followed by questions from curious shoppers: Who are all these Asians, and what are they doing in southwest Missouri?

While bagging bouquets of lettuce at the Neosho Farmers’ Market, Song Lee often answers questions that go something like, “Where are you from? No, where are you really from?” She finds it simplest to name a country of origin: Laos or Thailand. But that’s only the start of her story. Song is Hmong (pronounced mung), an ethnic Asian minority with a long record of persecution. Her people’s geographic history encompasses the shifting borders of China, Burma, Vietnam, Laos, and Thailand.

Of those faraway places, Song knows little. She was born in a Thai refugee camp and arrived in the United States as a child. “I remember it like dreams,” she says. “Sometimes I taste things, and it reminds me of back when I was little.” Song grew up in Minnesota’s Twin Cities but, like many Hmong, her parents traded urban life for agricultural opportunities in 2005, migrating to southwest Missouri. They sought a better life with the move, investing emotionally as well as financially in the land. To the Hmong, owning a farm symbolizes a return to their roots.

“For the elders, this place here in the corner of Missouri feels more like the country that was home,” says Wa Yang, founder of the Southwest Missouri Hmong Association. “That’s why so many people, when they retired from factories, moved down here.” Today Wa and his wife, Angela, live on a 57-acre farm with ten chicken houses near Purdy. They were one of the first Hmong families to arrive in southwest Missouri in 2002. Fifteen years later, Wa estimates, there are roughly 150 families, totaling perhaps 800 Hmong, in the region. “They like the weather,” he says. “They can garden outside, raise chickens, some cattle or pigs, and they don’t feel too homesick.”

Wa and Angela came to the United States as teenagers in 1989. Like Song, they also lived in a Thai refugee camp. Their stories offer glimpses into the greater Hmong legacy. For thousands of years, Hmong farmers lived in isolated mountain villages in Southeast Asia. As communism spread across the region, the Hmong saw it as a threat to their sovereignty. During the Vietnam War, the CIA quietly recruited Hmong soldiers—estimates vary from 20,000 to 60,000—in a covert operation now known as the Secret War in Laos. In the dense and seemingly unnavigable jungles of the Laotian highlands, Hmong soldiers assisted American interests by engaging in intelligence gathering, guerilla warfare, and air strikes. The United States began withdrawing troops from Southeast Asia in 1973, and one year later, the Laotian government fell to communism. Hundreds of thousands of Hmong— now considered traitors to the new regime—fled to Thailand. After years in refugee camps, many finally gained asylum in the United States, where they started new lives in a place whose citizens had little to no knowledge of the Hmong contribution and sacrifice.

“I was a little confused when I went to high school and read history books and didn’t see nothing of Hmong culture,” says Tommy Her of Noel. “I’ve always heard stories from grandparents, uncles, cousins, telling about the war and their escape and the hardships they had to go through just to come to the United States. But the majority doesn’t know about us and how we got here.”

Most Hmong initially settled in urban areas of California, Minnesota, and North Carolina, where they quickly found manufacturing work. But first-generation immigrants, most of whom had been farmers in Laos, held tight to the dream of someday returning to agrarian life. When buzz spread about poultry opportunities in the early 2000s, the Hmong began moving to southwest Missouri.

Del Oney, owner of Oak Ridge Shavings in Lockwood, first became acquainted with the Hmong when he began supplying shavings to Hmong chicken houses. “They started coming into this area one by one and then, all of a sudden, within a year or so, they were knocking on people’s doors to buy chicken farms. Literally, you didn’t have to have a Realtor if you wanted to sell,” he says.

The purchases were not always wise ones. Over the next few years, many Hmong poultry operations across the Ozarks failed. The overappraised, risky ventures, backed by loans from the US Department of Agriculture’s Farm Service Agency, brought little risk to lenders and allegations of fraud from critics.

But Addie Lesher, a now-retired real estate agent who worked with Hmong buyers in southwest Missouri, says she saw nothing sinister in that frenzied buying period. Addie, who has raised chickens and knows the challenges firsthand, notes that raising poultry is a hard life for most farmers, and not just the Hmong. “Did they know what they were doing? Yes and no,” she says. “But that’s just life.”

Many Hmong poultry farmers left the area after their operations collapsed. Those who remained either succeeded or found themselves supplementing poultry incomes by selling produce at nearby farmers’ markets.

“Because our chicken business was only enough to pay bills and not enough for recreation, the farmers’ market and my garden was a way to save money for other things,” says Mao Her of Noel. For more than a decade, Mao grew and sold hundreds of pounds of tomatoes, okra, squash, rice, flowers, and more at half a dozen farmers’ markets.

[mks_pullquote align=”left” width=”300″ size=”24″ bg_color=”#000000″ txt_color=”#ffffff”]”The Hmong were skilled gardeners who introduced diverse crops. They brought tons of what they liked to eat, but there wasn’t a market for that yet. Sales suffered.”[/mks_pullquote]

As the Hmong presence at these markets grew, it became obvious that they were skilled gardeners who could introduce diverse crops such as bitter melon and snake gourds. Hector Troyer of Stark City—also a seller at the Webb City Farmers Market—says he appreciated learning about Hmong crops.

But the exotic crops did not appeal to those with less-adventurous palates, and Hmong vendors suffered with low sales. “They brought tons of what they like to eat, but there just wasn’t a market for that yet,” Hector says.

During routine site visits to farms for the Webb City Farmers Market, Eileen Nichols noticed a troubling pattern: Although the Hmong excelled in growing traditional Asian produce such as bok choy and daikon radish, they struggled with tomatoes and other vegetables that might sell better.

“One farm we went to had 1,000 unstaked tomato plants, and they were watering them with lawn sprinklers. So they were losing 80 percent of their crop right there on the ground,” Eileen says. Operating under the credo that when a farmer succeeds, the market succeeds, Eileen secured a Project for Public Spaces grant from the W. K. Kellogg Foundation for the Webb City Farmers Market, earmarking a portion of the funds specifically for Hmong farmer education, including the hiring of an interpreter. The outreach worked. A year later, the Webb City Hmong vendors were reporting anywhere from 200 to 800 percent increases in profits.

“We continue to do training targeted at the Hmong, but the programs are open to everybody,” Eileen says. “We just always make sure the Hmong know what is going on and provide full translations. When one farmer becomes knowledgeable, they can help other farmers. That’s how it works with any culture.”

In 2015, the Webb City Farmers Market received a $60,000 grant to build a Winter Production Education Center to host demonstrations in high tunnel construction, seed starting, and more. The center is managed by Fue Yang, a horticulture student at Crowder College in Neosho and a second-generation Hmong. The center is located on his family farm, where he lives with eleven family members, including his parents, Neng and Zoua, who moved from Massachusetts after retiring in 2010. In their first garden, Fue followed his parent’s traditional but laborious methods, handpicking weeds instead of using mulch.

“I wanted to know what it felt like to do things the way they did in Laos,” Fue says. “And it’s a lot of hard work.” It was also inefficient, and there was a lot of what he calls “accidental waste,” which meant that their market sales suffered. Eileen asked Hector Troyer to partner with Fue, and between his mentorship and added guidance from the Extension Service, things began to change for the better.

Fue’s farm and the education center are located outside of Rocky Comfort, amid southwest Missouri’s tumbling hills and rocky creeks. From the road, Fue’s white high tunnels appear large yet unassuming. Inside, they house a portal to Eden. Neat rows of lettuce, kale, and spinach line the ground. A fountain of carrot tops stands alert nearby. There are beets and broccoli and cucumber. Plump tomatoes hang from trellises arranged with militant precision. Fue’s tomato crops always failed until the introduction of a suspended trellis system, which enables better ventilation and light than a typical tomato cage.

It has been a life-changing education for Fue and his family. “At first, my parents thought it was kind of weird,” he says. “They were like, ‘Just go plant stuff and grow it. What else do you need to learn about it?’ But there’s so much more that we don’t know about. I’m trying to do things more efficiently. I’m trying to bring modern to the farm.”

Despite modern agricultural practices, the Hmong preserve their culture. For most Hmong, clan structure, food, religious practices, and ceremonies surrounding births, weddings, and funerals are still very much alive. A popular event is Hmong New Year, typically celebrated at the end of a growing season to thank their ancestors for the harvest. In southwest Missouri, the Hmong New Year celebration takes place in an auxiliary hall at the Crowder College campus in Cassville. The event draws hundreds of Hmong dressed in the elaborately embroidered skirts, sashes, head coverings, and the silver jewelry of their ancestors. Celebration activities include dance performances, ceremonial games, and eating traditional dishes such as the meat salad laab and stir-fried vegetables. But modern western life creeps in. Everyone carries a smartphone and wears clothing made in factories rather than sewn by hand.

“We embrace change because it’s more comfortable,” says Shelly Yang, the youth leader of the Southwest Missouri Hmong Association.

Last year was the first year women were permitted to serve on the committee of the Southwest Missouri Hmong Association, which means a lot to women like Shelly. Traditional Hmong culture is patriarchal. Sometimes it manifests in small ways—such as banning haircuts for young girls because the culture equates hair length with a family’s good fortune—and other times it’s more complicated.

“My mom says, ‘No matter what, the man is always right,’ but I don’t think like that,” says Song, although she isn’t sure her untraditional opinion means she has become Americanized. “Does it sound like that?” she asks. “I just don’t know what American means anymore.”

Language helps define what it means to be an American. Song speaks both fluent English and fluent Hmong. “It traces you back to your ancestors, and you don’t ever want to lose that,” she says. “I never saw my grandpa because he stepped on a mine and died, but it always makes me wonder what he looked like, or how my grandma looked, and what their moms and dads were like.” Though she’ll never know those answers, it comforts her to know she still shares a common language with long-gone family members.

[mks_pullquote align=”left” width=”300″ size=”24″ bg_color=”#000000″ txt_color=”#ffffff”]”Hmong culture is patriarchal, which manifests in small ways, such as banning haircuts for young girls. Last year was the first year women served on the committee of their association.”[/mks_pullquote]

Many Hmong share the desire to preserve their language. “I want our language to stay alive because I want people to know that we are Hmong. God created us this way, and I don’t want to lose that,” Mao says. She came to the United States in 1980, after losing her brother in the war. “I want us to keep speaking Hmong, but I don’t really care if we lose the culture. I want my kids to continue their education and speak English fluently. I want them and my grandkids to live here like any other American would. I gave my life working and giving all the energy I have to make sure that my kids can live life and the American dream: have good jobs, an education, and build a future.”

Language matters less to other families. Nandy and Seng Yang of Granby live on a picturesque farm with cows in the pasture, chickens underfoot, an enormous garden, and a yellow farmhouse at the end of a treelined lane. Seng is a first-generation Hmong who sells produce in Neosho and Springfield. Nandy, who was born in Massachusetts, teaches fifth grade. Their six children are a chorus of fun-loving farm kids whose priorities and chores mirror any other family—fold laundry, finish homework, and so on. They’re learning to drive. They like fast food. And when Nandy and Seng speak to their children in Hmong, the kids understand the language, but choose to respond in English.

“Right now, my children cannot talk Hmong,” says Seng. “I speak to them in Hmong but they speak back in English. It matters a lot to other people, but not to me. I don’t care because they need to work at being American. The more they learn and have good grades, that’s the best.”

Over and over, first-generation Hmong parents emphasize the importance of education and economic mobility for their children. Assimilation is simply part of the package.

“Every family is different, but I want my kids to have a better life,” says Wa Yang. “They will have better than us, and I have had better than my parents. We are Hmong American, but my children will be American Hmong.”

Related Posts

Meet the Holy Trinity of Conservation on a Missouri Farm

The Holy Trinity of Conservation takes place at Prairie Star Restoration Farm in Bland on Saturday, June 3. Tickets are $20 for adults, and $10 for students. There is a special reserved evening dinner on June 2 for $100 per person.

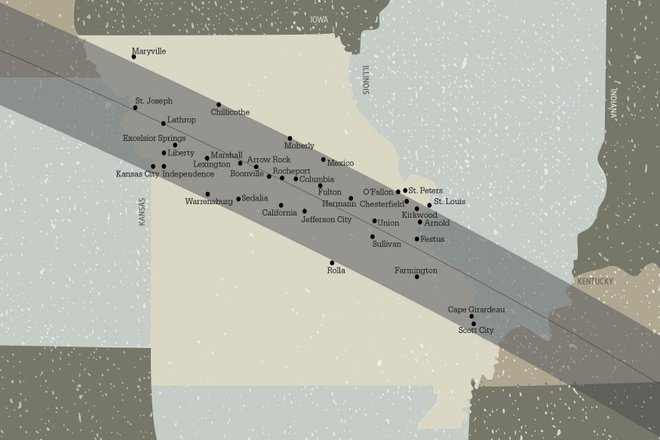

Everything You Need to Know About the Missouri Total Solar Eclipse 2017

More people in the Show-Me State are expected to experience the totality of the eclipse than any other state along the event’s path.

The Birdman of Salem

Artist David Plank can’t remember a time when he wasn’t drawn to birds. While his boyhood friends were busy kicking soccer balls and hitting baseballs, David was in the woods of Salem with paper and pencil, capturing the details of a perched barn swallow or a purple martin.