This article was originally published in our March 2020 edition..

Very little remains of the once massive cottonwood tree Walter Elias Disney called his “Dreaming Tree.” The coarse, woody debris is an anchor tying a small town in Missouri to the pioneer of the American entertainment industry. It was under the several-feet-wide tree that Walt Disney began to conceive some of his most beloved characters.

Walt spent his boyhood years in Marceline, years he referred to as the best time of his life. Young Walt would sit under the tree on his family’s farm just outside of town, with his sister, Ruth, while his three older brothers— Herbert, Raymond, and Roy—worked the farm with their father. It was Walt’s job to babysit Ruth, but he would later confess that he spent his time under the tree dreaming. There, he began inventing the first few assemblages of a new world, where walking and talking objects and animals would transform the mundane to the magnificent.

He called the time he spent under the Dreaming Tree his “belly botany” adventures; lying on his stomach, he observed the bugs, animals, and birds and listened to the sounds of the wind, all the while gathering the dreams that would inspire Mickey Mouse and Silly Symphony cartoons.

Walt never outgrew his love of the Dreaming Tree, despite moving away from Marceline around 1910. Inez Johnson, whose family now owns the land where the tree is located, hosted Walt and his family during their 1956 visit to Marceline. She remembers his amazement that the tree still stood on the land that used to be his father’s farm. During the trip, Walt and his brother Roy took time to visit the tree and reflect on what Walt’s imagination captured under the branches. Inez remembers: “He said: ‘I drew whatever we saw. I could always count on rabbits and squirrels and fi eld mice. And on a good day, sometimes Bambi came by.’” The Dreaming Tree was registered as a historic tree by American Forests.

An adult Walt treasured the time he spent growing up and dreaming in the small northwest Missouri town, where he said he experienced the defining moments of his childhood. He wrote to The Marceline News in 1938, “More things of importance happened to me in Marceline than have happened since—or are likely to in the future.”

Walt’s recollections of Marceline inspired the design of Disneyland’s Main Street USA attraction. His nostalgia inspired the films So Dear to My Heart and Lady and the Tramp. And, most importantly, many of the Disney characters adored by millions today were spawned by his memories of his boyhood in Marceline. The town’s motto captures in five words the significance of Marceline to the life and legend that was and is Walt Disney: “Where Walt found the Magic.”

It’s a Small World After All

The mighty cottonwood finally fell on May 28, 2015, presumably from a “particularly strong wind storm that blew through Marceline,” according to accounts from the Walt Disney Hometown Museum. The wind was the final assault on the tree following years of disease and repeated lightning strikes. An open-ended wooden fence protects what’s left of the beloved tree, which sits about fifty paces from a replica of the original Disney barn, built by volunteers in 2001.

People from across the globe visit the barn. They have written thousands of notes, verses, and signatures in many languages on the rough-hewn walls and beams. Walt held his fi rst theatrical production in the original barn, charging his friends a dime to witness a circus entourage of barnyard animals dressed in toddlers’ clothes.

Although Walt was born in Chicago on December 5, 1901, Elias and Flora Disney moved the family to Marceline when Walt, their youngest son, was four years old. In that fi rst year in Missouri, Walt sold his first drawing to a neighbor and attended a play at the now-closed Carter’s Opera House. The play was Peter Pan, a role he reprised at his elementary school while brother Roy manned a block and tackle that enabled Walt to fly.

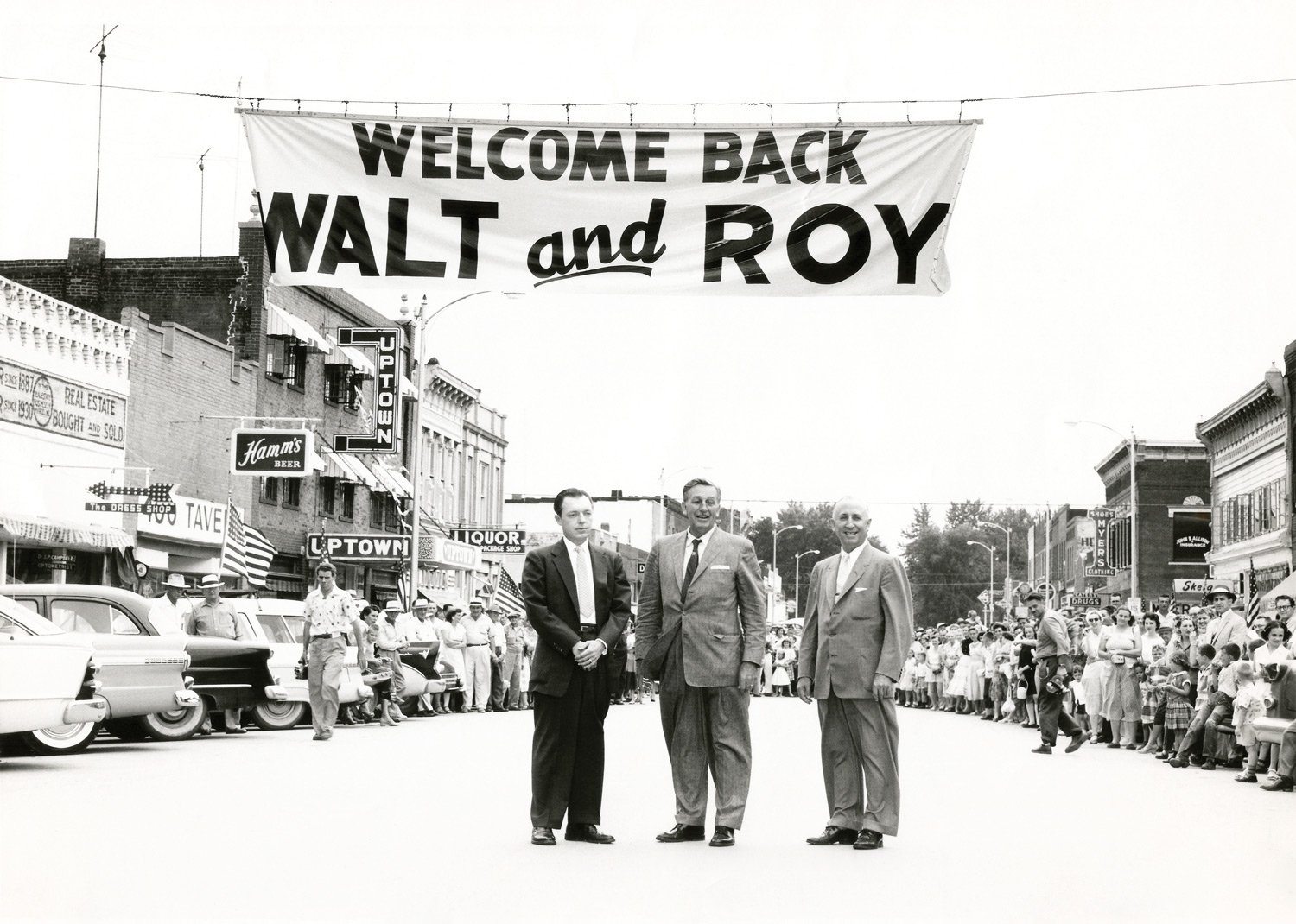

Walt spent a great deal of time in the Missouri town with his uncle, Mike Martin, a Santa Fe Railroad engineer, says eighty-one-year-old Jack White, a lifelong Marceline resident. “That’s where Walt got a lot of his stories about the railroad,” recalls Jack, a forty-three-year veteran railroad conductor. In their 1956 return to Marceline, Walt and Roy sponsored the Midwest premiere of The Great Locomotive Chase at the Uptown Theatre. Based on the real Great Locomotive Chase of 1862, the Walt Disney Productions and CinemaScope adventure fi lm was a testament to Walt’s love of trains—and Marceline.

Today, the Walt Disney Hometown Museum is housed in the 10,000-square-foot Santa Fe Railroad station in Marceline. Built in 1913, it sits on the same piece of land where Walt and his family stepped off the train from Chicago in 1906.

“We are actually the first museum dedicated to the life of Walt Disney,” says Kaye Malins, founding board member and daughter of Inez and Rush Johnson, who own the land where the barn and the Dreaming Tree sit. Museum director since 2001, Kaye still lives in the Disney home on the original Disney family farm in Marceline. Walt Disney and his brother, Roy, stayed with Kaye and her parents in 1956 on a trip for the dedication of Marceline’s Walt Disney Swimming Pool and Park. It was one year after Disneyland opened in California.

That time spent with the Disneys provided Kaye and Inez, who is also a founder of the museum, with a lot of the details they now share about Walt and his family. “We tell the story of the family, not just the company,” Kaye says. “It’s what sets us apart from everyone else. It was Walt’s time here in Marceline—the only time he got to be a kid—that he cherished. He spent the rest of his life trying to re-create his time here.”

Kaye says it shows in his movies and parks. “He made a conscious decision that you can’t go anywhere in Disneyland without walking through that town,” she says.

Marceline holds a special place in the hearts of the rest of the Disney family, too. “When Walt and Roy told their parents they would send them anywhere in the world they wanted to go for their fiftieth wedding anniversary, the Disneys chose Marceline,” Kaye says.

Peter Whitehead, creative director of the Walt Disney Hometown Museum, points out that Walt spent a “weirdly short period of time” in Marceline—about four or five years—but that he later gave the town an identity. “The greatest advocate for Marceline was Walt Disney himself,” Peter says. “The greatest gift he gave Marceline was that he told the world he loved Marceline. He told the world that the greatest place in the whole world was Marceline, Missouri.”

The Marceline Project

A life in Marceline wasn’t in the plans for Peter Whitehead. A Canadian, Peter was only going to stop over for a visit when he drove to Marceline two years ago, on his way to take his son to his new job at Epcot Center in Florida. The two Disney devotees decided to visit the town of 2,200 people where Walt had spent his childhood. Like most visitors to Marceline, they made their way through the town’s business district, which stretches three blocks along Kansas Avenue. The single main street has remained largely unchanged in the one-hundred-plus years since young Walt’s arrival from Chicago.

Peter was considering doing a documentary on Marceline when he found out the museum was hiring. Since being hired on, he has assisted with renovating the museum and deepening its relationship with The Walt Disney Company. Today, the Disney Company is made up of media networks, parks and resorts, studio entertainment, consumer products, and interactive media. It does not currently support the museum financially, Peter says. Despite Walt’s reverence for the town, the relationship between the Disney Company and Marceline hasn’t been steady, especially since Walt’s death in 1966. The long-lasting connection between Marceline and the Disneys has instead been fueled by personal efforts of those in Marceline, the Disney family, and Walt’s imagination.

Kaye says Walt spent the last ten years of his life working on a project especially for Marceline. Walt had decided on his trip to Marceline in 1956 to purchase his boyhood home and farm and develop a rural experience around it, calling it the Marceline Project. Walt and Roy purchased 300 acres, including the original farm, on which they planned to build a theme park. They ran the deal through the brothers’ corporation, Retlaw Enterprises, which is Walter spelled backward.

“The Marceline Project was going to be a general living history farm in Marceline, where it all began for him,” Kaye says. “He said, ‘There will come a time when a child won’t know what an acre of land is or what happens when you put a seed in the ground.’ He wanted to have a working 1900s farm to show them. The land had been purchased. The feasibility studies had been done. The governor of Missouri was going to put a four-lane highway in to Marceline. And then Walt passed.”

After Walt’s death in 1966, Inez and Rush Johnson bought forty acres of the land that had been intended for the Marceline Project—the area that preserved the Dreaming Tree, the barn, and the farmhouse—and the rest was sold off.

Peter says the person in charge of the Disney archives was stunned to discover that Walt’s original sketch of the Marceline Project is located in Marceline. “The head of the archives had no idea the drawing existed,” Peter says. “Roy Disney had taken it out of Walt Disney’s office after he died and brought it back to Marceline.”

The Disney siblings were instrumental in keeping Walt’s connection to the small Missouri town alive after his death. Ruth, for example, developed the Walt Disney Hometown Museum and provided the family artifacts on display. “The only reason the museum exists is because of Walt’s sister, Ruth Disney,” Peter says. “She had an unbelievable collection of artifacts from her brother, and the only place she wanted them displayed was here.”

Many of the items in the collection provide a deeper view into the relationships within the Disney family, such as the 1955 RCA Victor Delux console television on display. According to Peter, Ruth did not like to travel. Not wanting her to miss the opening of his beloved and personally designed Disneyland on July 17, 1955, Walt purchased the television for his sister so she could watch the opening-day festivities. Walt’s sister left that television to the Walt Disney Hometown Museum.

Homecoming

Inez Johnson, now eighty-seven, was born and raised in Salisbury, just thirty miles from Marceline. “This is as far as I ever got in life,” she quips.

Her family has been closely entwined with the Disneys for a couple of generations now. Rush, Inez’s husband, was the person who sparked Walt and Roy’s return to Marceline in 1956.

The year before their homecoming, the good people of Marceline voted in favor of a bond issue and built themselves a swimming pool. Rush Johnson was on the city council. “Rush came home and said, ‘We should try to get Walt Disney to use his name on our pool,’” Inez says. “The city pooh-poohed the idea. They said, ‘Walt Disney was only here five years. He probably won’t even remember he lived here.’”

But, Inez says, Rush figured what did he have to lose? “When Walt got our letter, he called immediately,” she says. “He said: ‘I have nothing but good memories of Marceline. It would be an honor to have my name on that pool. Marceline was my only childhood.’”

After that, the question for the people of Marceline became one of what to do with the Disneys during their stay, Inez says. “The hotel was run down. There was no air conditioning. We didn’t want to send the Disneys out of town.”

It just so happened that Rush and Inez had built a new house the year before at 905 North Kansas in Marceline. And because they had helped a friend who was getting into the air-conditioning business and wanted to try out his new product on their house, the Johnsons had central air.

There was only one more problem. “I reminded my husband that we had spent my furniture money on the air conditioning,” Inez remembers. “We thought, ‘We can’t have the Disneys on the hand-me-down furniture.’”

But the community found a way to provide. “Of course, everyone in town knew the Disneys were coming,” Inez recalls. “In those days, we didn’t have social media, but word got around. Our friends had very nice furniture, but no air conditioning, so they said, ‘We’ll help you.’ And they furnished our house with their good stuff. Then they hired the chef of the Santa Fe Railroad driving car to cook for the Disneys while they were here. What an impression we made with that chef’s hat.”

For all of their fussing, the food and furniture made little difference to the cartoon mogul, who just wanted to reminisce about afternoons spent under his Dreaming Tree. “As it turned out, they were the dearest, warmest people,” Inez says.

During the dedication ceremony, Walt reportedly told the children of the town: “You are lucky to live in Marceline. My best memories are the years I spent here.”

Walt again returned to Marceline in 1960, when he dedicated the Walt Disney Elementary School. At the dedication, Inez says Walt stated: “I’m not a funny guy. I’m just a farm boy from Marceline who hides behind a duck and a mouse.” Walt donated a flag pole from the Squaw Valley Olympics, and a Disney artist decorated the interior of the school with Disney murals. Both touches of Walt are still present at the school today.

In 1966, the brothers moved the Midget Autopia Ride from Disneyland to Marceline’s Walt Disney Municipal Park, where it ran for eleven years. It remains the only Disney ride ever to be relocated. Inez says the Disneys were scheduled to dedicate the ride in July of that year, but Walt canceled at the last minute due to “a hacking cough.” He died on December 15, 1966, from complications of lung cancer.

After that, the Marceline Project came to a halt. “When he died so young, nothing happened here for forty-five years,” Inez says. “It was horrid. All the newspapers had Mickey Mouse with tears. We mourned with the world.”

Although Walt’s death dampened the Disney magic in the town for a time, careful cultivation is bringing it back. Now, Kaye, Peter, and the team at the museum frequently travel back and forth from Marceline to both Disneyland and Walt Disney World. At the Official Disney Fan Club’s D23 Expo this past July in Anaheim, the museum announced The Dreaming Tree Gala, a benefit on November 18 at the Contemporary Resort in Walt Disney World. Robert Wilson, former chief operating officer and chief executive officer of Retlaw, will publicly discuss his relationship with the family for the first time at the event. Tickets are available at the museum’s website.

It’s thanks to the excitement and passion from the folks at the museum and in Marceline that Walt’s legacy is still alive in Missouri. Without the people of the town holding onto the magic, the Dreaming Tree might have faded from memory. In 2004, Walt’s grandson Bradford Disney Lund and three Walt Disney World Ambassadors brought soil from the Magic Kingdom and water from the Rivers of America to plant a sapling on the Disney farm about twenty feet from the Dreaming Tree. The sapling was grown from a seed harvested from the original Dreaming Tree. Thus, the “Son of Dreaming Tree” was born on the Disney farm, rooting Walt again in the land of Marceline.

Related Posts

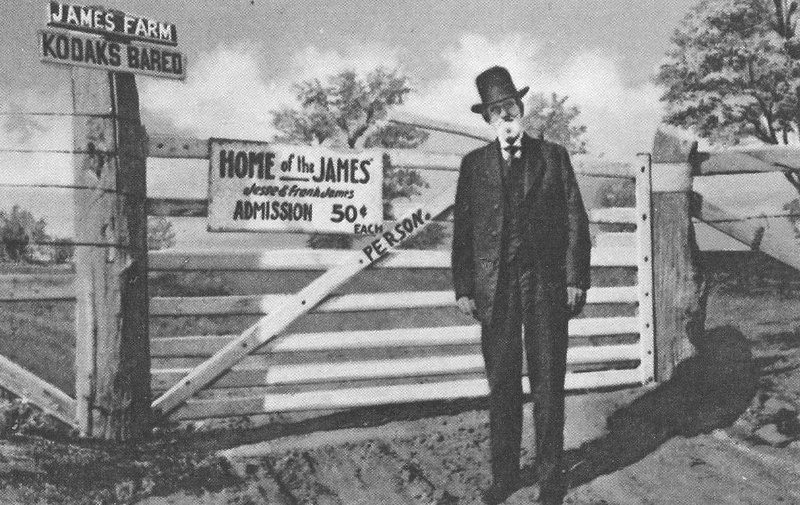

June 28, 1902

It was announced that Frank James had decided to live again in Kearney, MO along with his wife. He also stated (through his attorney) that his aged mother was planning to live with them.

December 18, 1963

Brad Pitt was born in Oklahoma. However, soon after his birth, his family moved to Springfield. He attended Kickapoo High School and went on to study journalism at the University of Missouri-Columbia.

The Birdman of Salem

Artist David Plank can’t remember a time when he wasn’t drawn to birds. While his boyhood friends were busy kicking soccer balls and hitting baseballs, David was in the woods of Salem with paper and pencil, capturing the details of a perched barn swallow or a purple martin.