How cave divers mapped the subterranean reservoirs at Missouri’s most popular state park.

This article originally appeared in the March/April 2022 issue of Missouri Life magazine.

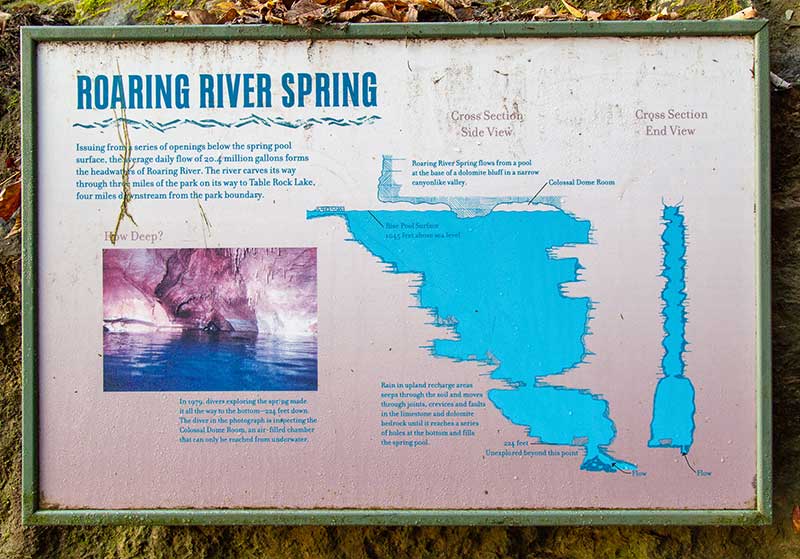

Roaring River State Park is beloved for its trout fishing but named for its preternaturally turquoise spring, which flows from the base of a towering, U-shaped bluff. At the viewing platform, its shadowy mouth is hauntingly beautiful, dappled with light and the shadows from hanging ferns. On average, the spring produces an unfathomable 20.4 million gallons of water per day.

Famed for its trout fishing and extraordinarily blue water, Roaring River State Park in Barry County is Missouri’s most popular state park. In 2020, it received more than 1.4 million visitors.

In 1979, divers surveyed the mysterious spring. Deep below the surface, at 225 feet, it narrows into a constriction where water flows with the force of an open fire hydrant. What lay beyond seemed fated to stay unknown. But in 2020, a team of expert cave divers finally gained permission from the Missouri Department of Natural Resources to map the source of this otherworldly water.

Among Missouri Speleological Society scientists, the value was scientific, and park superintendent Joel Topham wanted a promotional film the divers promised to produce. But for expedition leader Mike Young and his team, it was about the thrill—and danger—of diving into the unseen.

When Young and his team first stepped into Roaring River last May, they didn’t know what awaited them, but Young, a dive equipment manufacturer and thirty-year cave explorer, was hopeful. His core team included cartographer Jon Lillestolen, underwater photographer Randall Purdy, and documentary filmmaker Tim Bass. Their dive was supported by a half-dozen other volunteer safety divers from around the country.

For observers at the surface, cave diving doesn’t look like much. To enable long dive times, they use rebreathers, a closed-circuit system that recycles oxygen Because the equipment weighs up to 160 pounds, divers gear up in the water. They test for leaks. And then they’re gone, their descent marked by cartoonish burps of bubbles. Occasionally, a flashlight beam cuts through the water, and then that disappears, too.

The expedition began with a 220-foot descent to set guidelines—the precious connection to the surface. Once there, the divers could already feel the constriction’s menacing current.

The expedition began with a 220-foot descent to set guidelines—the precious connection to the surface. Once there, the divers could already feel the constriction’s menacing current.

So many things can go wrong in a cave dive. Currents yank off mouthpieces. Guidelines snap. Worst of all, re-breathers fail. And sure, support crews stash emergency tanks, but the best mitigation is a methodical dive plan that everyone adheres to without exception. Proper decompression stops are also crucial. Ascend too quickly, and a human’s blood will fizzle with nitrogen, as divers love to say, like a shaken soda bottle. In Roaring River, decompression stops are staggered by ten-foot intervals and last for hours. To pass the time, some divers just swim around trying to stay warm. One reads Louis L’Amour novels sealed in plastic bags. Young watches subtitled TV shows on a cellphone.

Later that summer, the flow dropped from firehose velocity to approximately fifty cubic feet per second—which Young likens to driving down the interstate at seventy miles per hour with his head out the window. Using brute force, the dive team pushed through the constriction, inch-by-inch, and into a broader passage—one no human had ever seen. The passage ended in a room where the current finally vanished. Young swam forward as though suspended in space, his light revealing nothing but an endless abyss.

When he returned to the surface two hours later, he described the discovery in two words: “Scary big.”

Four hundred million years before Missouri became prairies and forests and low-slung mountains, it was a shallow sea. Brachiopods and crinoids filtered the water. After dying, they calcified into the ocean floor. Even today, you can sift through the rocky bottom of any Ozarks creek and find these fossils.

Over timespans that seem glacial compared to human lives, the landscape we now know emerged, but beneath it, remnants of that ancient sea persist. Its sandy bottom became a limestone crust that fractured along fault lines that rain patiently carved into the aquifers from which we drink.

“Because of the karst topography of the Ozarks, Missouri has some of the most wonderful, beautiful, plentiful springs in the United States. Understanding that is very important. It’s a very unique and valuable resource for all Missourians.” —US Geological Survey hydrologist Ben Miller

Before development, Roaring River emerged from the floor of the overhanging bluff. Like a shell pressed against the ear, the surrounding rock amplified the sound of the water.

Behold: a roar.

In 1865, valley settlers built a dam to power the McClure Mill, which ground grain and spun fiber for yarn. The settlers prospered, but their dam confined the spring and silenced the water forever. The area became a park when Thomas Mark Sayman—a local eccentric who made his fortune selling soap—purchased and then donated the property to the state in 1928. (Rumors claim he bought the land for trout fishing but never caught a thing.) The 1930s brought Roosevelt’s New Deal and the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), which built recreational cabins, roads, trails, fish runs, and hatchery buildings.

Today, pedestrians on the spring’s viewing platform parallel the stone block run installed by the CCC nearly a century ago. Even when summer is at its hottest, the park is always a few degrees cooler than the surrounding area thanks to its topography—and the river stays a biting fifty-seven degrees, the same temperature as the cave at its source.

Park supervisor Joel Topham grew up nearby. He spent his boyhood summers at Roaring River with his grandparents.

“For me, it was always a magical place. And when I talk to the families that camp here, most people feel the same,” he says. Today, he lives in the park. “I see it all day, every day. I try to wake up every day appreciating where I’m at. Our whole team—naturalists, maintenance, even the temporary workers—our goal is to instill a sense of respect for nature and pass that on. We have to make this place matter.”

Topham sees the scientific findings of the dives as an opportunity to enrich the public’s emotional connection with the park. From his observations, visitors already treat the spring with an inexplicable reverence and awe, and that’s something he hopes all Missourians eventually experience.

“The spring is one of the biggest draws,” he says. “There are people that just come to sketch it. They’ll go and meditate. They’ll pray. They’ll ask for hands in marriage. Or they’ll just sit and reflect. There’s so much hidden and unknown about it. The dive gives us a sense of how grand, how large it is. And maybe we’ll never truly know. But it puts things in perspective. It gives me a true idea of how small I really am in the world.”

In 1981, an ammonia fertilizer pipeline spilled, threatening wildlife sustained by Missouri’s fifth largest spring: Maramec Spring near St. James. Aided by recharge maps, local officials knew it would take the ammonia three to seven days to reach the spring, and they saved wildlife from deoxygenated water by moving the animals into temporary holding pens until the contaminate passed.

No such map of Roaring River exists … yet. That absence leaves it, and Barry County’s economic engine, vulnerable. That’s where US Geological Survey hydrologist Ben Miller and retired soil scientist Bob Lerch come in. Using fluorescent dye tracing, the duo has studied the region for the Cave Research Foundation for years. Strangely, dye from nearby hollows never resurfaces in Roaring River, but dye injected into prairie sinkholes five miles north of Cassville does.

“We think the water needs to be far away for it to have enough travel time to get into the spring conduit. The fact that Roaring River’s spring is so deep supports that theory,” Miller says. “What we’re seeing in southwest Missouri are big vertical systems, and the diving helps us learn more about it every time they go. Bob and I aren’t cave divers. Those guys are in it for the exploration—but they’re complementary interests.”

Expedition leader Mike Young, above, has been cave diving around the world for the past thirty years. —Rose Hansen photo

Together, the scientists and divers are creating a map of the spring’s recharge area so that state officials can better understand the exact path of contaminants and water usage threats. Its long-term utility is two-fold: It can help local officials protect the trout-fishing economy from contaminants, and it can help assess future water supplies.

“Southwest Missouri is projected to grow a lot, and our biggest stressor on groundwater is residential and urban. [The town of] Noel has already drawn its water down. If we have a population that’s reliant on groundwater with a bunch of drilling and pumping out of it, that could affect this spring. In the future, if they want to conserve Roaring River for the hatchery, they can’t drill in this recharge area. That’s just another example of how people could use this as a management tool in the future. It’s all tied together,” Lerch says.

Miller and Lerch aren’t naïve and know that talk of long-term sustainability isn’t always politically popular. That doesn’t discourage their efforts.

“We’re just trying to make a tool for the future,” Miller says. “Because of the karst topography of the Ozarks, Missouri has some of the most wonderful, beautiful, plentiful springs in the United States. Understanding that is very important. It’s a very unique and valuable resource for all Missourians.”

More people have visited the moon than Roaring River’s deep veins.

In October, Young found something solid in the “scary big” room at 451 feet: a rock platform that stairstepped into shadows. Absence of silt indicated a current—another inlet of water. The deeper source that filled the room was close. Twelve feet remained to beat the national record: the 462-foot Phantom Cave Springs in Texas. But he’d promised his team he’d stick to the plan, and it didn’t include those depths.

As the minutes passed, his decompression time in the cold, dark water multiplied exponentially. With just eleven feet left, he ascended. The new national record for the nation’s underwater cave would have to wait.

But for Missouri? History had been made. Roaring River was the deepest spring in the state. With torrential rains in the forecast, the team feared the dive season was over for the year, but the rain never came. Two weeks before Thanksgiving, Young descended again, this time to the deepest underwater cave in the nation: 472 feet.

It’s a claim that makes Topham beam with pride. And if social media is any indicator, the public shares the sentiment.

But as Young puts it: “Eh. It feels the same. It didn’t change anything.”

That’s the funny thing about highly technical adventures. To those directly involved, achievements like this are just the slow culmination of years of training. For the rest of us, it’s tough to resist romanticization and awe.

More people have visited the moon than Roaring River’s deep veins. Like the moon, it’s a place we’ll likely never see for ourselves. We’re just left to revel in knowing that it’s there and—best of all—it’s ours.

KNOW & GO

SLEEP | In-park lodging abounds at Roaring River. Choose from standard rooms at the Emory Melton Inn, rustic suites in the historic stone CCC Lodge, or stand-alone riverside cabins nestled between the water and the woods. Prices range from $119–$159 per night.

EAT | Hit the in-park Emory Melton Lodge for a hearty homestyle menu that boasts everything from burgers to fresh fried chicken. If you’re craving more variety, Cassville is just 10 minutes away and offers everything from fast food to full-service restaurants. Our pick? Tacos at the no-frills El Mariachi on the edge of town.

PLAY | Fishing and spring-gazing aside, there’s plenty to see. Devil’s Kitchen Trail is easily the park’s best of seven hiking trails (1.4 miles), as it meanders by stone outcrops, bluffs, and even caves. Not a hiker? Visit the Ozark Chinquapin Nature Center, which offers multiple interpretative programs like wildflower workshops and bald eagle viewing. Have fun feeding the fish!

Related Posts

Revitalizing Missouri Downtowns

Here’s how Missourians are working together to revitalize downtowns across the state.

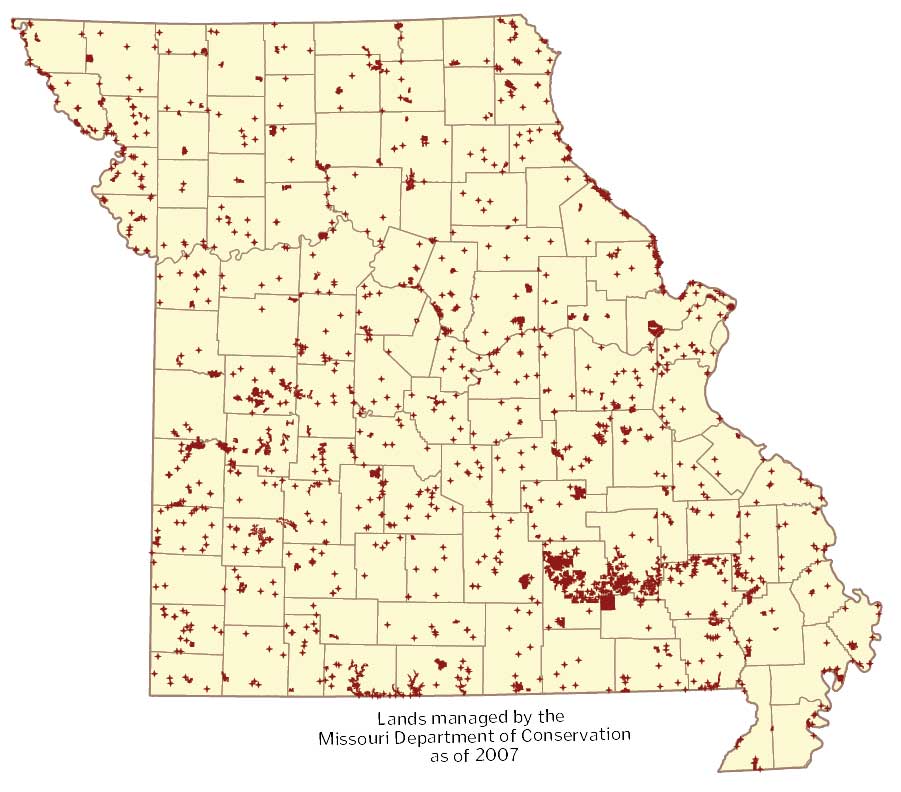

STATE-TISTICS: Conservation Areas in Missouri

Conservation areas by the numbers