Art imitates life, or maybe life imitates art. Either way, the two are connected, and the work of Columbia artists Tony and Bethanie Irons, a husband-and-wife duo, is a reflection of what they see and an interpretation of how it affects them.

Bethanie

Growing up in South Dakota, the extent of Bethanie’s artist community was watching Bob Ross on PBS. Painting was her passion then, and she pursued a bachelors of fi ne arts and a masters of fi ne arts in the medium, and later, a doctorate in art education. After graduation, however, her studio shrank dramatically. With no room for large canvases, paint palettes, and tubes of paint, she turned to her laptop and created a new studio in the digital world.

“I’m a little obsessive with things,” Bethanie says. “With painting, I couldn’t get the hard edges or the perfect lines that I can get by doing things on the computer.”

She confesses she frequently returns to her works and corrects aspects she isn’t happy with. Digital art gives her the fl exibility to experiment, but converting to digital wasn’t easy for her.

“There was a big learning curve for me,” she says. “I started doing very simple things on the computer because, I guess, technically I’m a Millennial, but I didn’t grow up with computers. Up until that point, I’d just used the computer for basic things.”

She hit her digital stride and discovered a new passion: teaching. An assistant professor of graphic design at William Woods University, she also teaches others how to create and share their work.

Bethanie has exhibited her work in both solo and group shows from the Midwest to Norway. In her latest body of work, the COVID-19 pandemic has made her turn inward.

“With the pandemic, it really forced everybody to slow down and to be home in a way that a lot of us don’t really get to be,” she says.

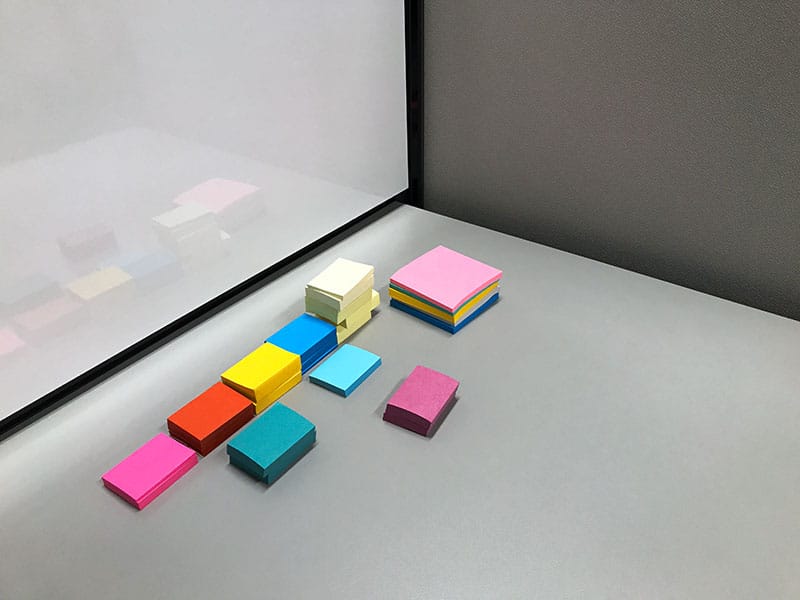

Bethanie began thinking about vanitas, a genre of still life that conveys the transience of life. Her work has come to include objects like cleaning supplies to symbolize warding off disease and calendar blocks to mark the passage of time.

“This new body of work has a lot more emotional energy in it for me because it was, and it still is, a very emotional time,” she adds.

Tony

Tony’s photography fascination began as a child when a parish priest, who taught math and photography in the ’50s and ’60s, took Tony under his wing and shared his passion for photos. When he died, he bequeathed his cameras and books to Tony. Other family members also encouraged his photography.

From an early age, Tony was influenced by the work of photographers who demonstrated that everything can be photographed and everything can be art.

“The thing for me is relating imagery to something that I’m trying to express,” Tony says. “Usually most of my work is focused around loss or grief. There’s a long history about coping and learning about grief from a very formative age. I see that kind of manifest itself in objects.”

to symbolize efficiencies in the office environment

At his job as a project manager for an office, he found a way to feed his artistic drive.

“I was trying to find time to come up with something that I could work with and get my mind excited about something. The technology that these [cellphones] have now is so fantastic that I just started photographing the things that people would leave on my desk.”

Trying to make a body of work out of those images was difficult until he zeroed in on office efficiencies. The objects came to represent all of the things that go on in a controlled and confined office environment. This series became labeled #dryerasecube.

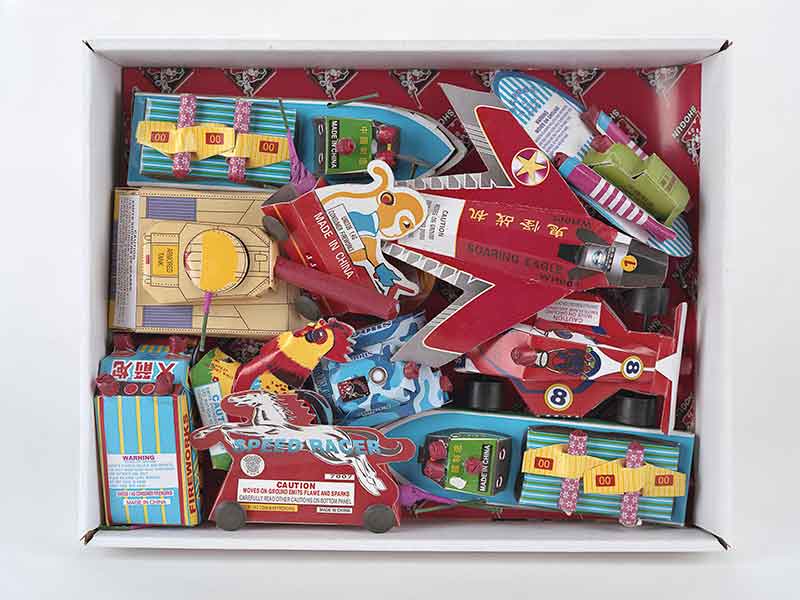

For #dryerasecube, the culture of excess was on his mind. “Anything that I had shipped to me at work, I would photograph it first. For me that was a way of calling myself out: look at all of this crap that I bought, look at all of my photo books, fi lm, and everything that’s come through.”

religion. Fireworks packages convey expectations and promises through words and images,

and he believes they are similar in construct to a large church.

Together

Both Tony and Bethanie’s work does more than paint pretty pictures of color and light for a viewer.

“If anything, art is the great connector for a lot of people,” Bethanie says. “You can share in experiences through art.”

Tony’s purpose is more selfish, he says. “For me, my work has always been me trying to work through something on my own. I don’t get really too involved with it, the statement about the work. I mean I do, but for some reason I feel like there’s going to be somebody that connects to a way that I’m trying to portray something.”

They both agree, though, that art brings people together.

“That’s what art does—gives us that broader perspective of things outside of your head,” Bethanie says. “Makes you a little more thoughtful about how you carry yourself in the world.”

Tony: “Yeah.”

Related Posts

Meet Clara Straight

Wide smiles and watercolors

Meet Multitalented Musician Tonina Saputo

At just 23, St. Louis-based singer/songwriter, upright bassist, and poet Tonina Saputo has accomplished more than many artists twice her age. As a high school student, she performed with her school’s symphonic orchestra at both Carnegie Hall and Lincoln Center in New York City.

Meet One of the World’s Last Calliope Builders

Dan, who builds Tangley calliopes today, is a quiet, religious man who methodically crafts “better, stronger” replicas of Norman’s ingenious, mechanical music contraptions in the shop behind his rural northeast Missouri home.