The audience inside the iconic Gem Theater is getting antsy. It’s almost 9 pm—an hour past the scheduled start of the 2018 Miss Black America pageant. The smooth jazz tunes and dimmed lighting were nice, peaceful even, for the first 40 minutes or so, but now the saxophone rendition of Al Green’s “Let’s Stay Together” is feeling a bit too literal. Everyone is ready for the show to start.

When the lights finally go down, the trumpet-led intro of Demi Lovato’s “Confident” reverberates across the theater, and 23 young black women in tall heels and black dresses stride onto the stage. The response is electric. Every step inspires an audience member’s “Yes, queen!” or “Mmm-hmm.” It’s not just that there’s finally something happening; the women on stage are moving with a visible fierceness and confidence, one that can’t be faked to appease a crowd. They’re not just up there to win a crown. They’re there to prove that being black is something to be proud of.

The 50th anniversary Miss Black America pageant has begun.

The pageant began five decades ago as a protest of the rhetoric that black was not beautiful. Over time, the pageant has helped shatter that stereotype and empower young black women to be proud of who they are.

The organization celebrated 50 years of this empowerment last August, when Kansas City hosted the pageant and the week of events leading up to it. The partnership between Miss Black America and Kansas City wasn’t without significance. Home to the 18th and Vine Historic District, where black businesses gathered in the 1900s and jazz blossomed in the 1920s, the city is full of black history and pride.

This history served as the backdrop for the equally historic 50th anniversary event of the Miss Black America pageant, and it was all filmed live for a national television special that will air in February.

Our next contestant is Ryann Richardson representing Brooklyn, New York.

Sportscaster and pageant host Charlie Neal’s voice booms across the theater, and Ryann, a tall, muscular woman with dark skin, walks to the front of the stage. Her smile is slight, almost a smirk, as if she knows she’s owning the room with her confident, strong walk. She pauses at the front of the stage and poses for the judges before striding away, as the emcee’s voice booms again.

Please welcome our next contestant …

Now introducing …

Our next contestant is …

There are 23 contestants ages 18 to 29. They came from around the country—aside from Kansas City contestant Sasha Washington—to compete in the 2018 pageant. Some won local pageants and advanced to the national competition; others were selected as contestants-at-large, based on their online applications.

They’ve prepared for months, even years, for this event. They found sponsors, raised money, picked their platforms, practiced their talents, and more. They spent a week in Kansas City attending press conferences, photo shoots, panel discussions, rehearsals, dinners, and pitch-off sessions. Two days before, they competed in the preliminaries to determine the top 10 in each category—swimsuit, talent, and projection (Q&A)—and the top 10 overall. And now, on this night, for the television taping, the top 10 contestants in each category are competing for the title of 2018 Miss Black America.

It’s a title Natasha Gallop—representing Atlanta, Georgia—didn’t even know she wanted, and one that took five months of self-reflection to fully understand.

In 2017, on a late December night, Natasha was at home scouring the web and applying for jobs. As an actress, she spends a lot of time searching the internet for potential gigs. In the wee hours of the morning, she says, she saw a listing for the Miss Black America pageant. She had remembered seeing something about a new pageant-focused film or television series and, tired and maybe a little sleep-deprived, she figured the listing was for an acting job. So she applied, and then, she says, “I just forgot about it.”

A month later, Natasha received a response from the pageant. She was a contestant for the national competition. “At first, I didn’t think it was real,” she says. She’d never even heard of Miss Black America. It wasn’t until February 2018 that she learned of the organization’s history and decided she wanted to be a part of it.

“This pageant is specifically the Miss Black America pageant. If there is anywhere in the world that I should be loving everything about myself that is natural, this should be the place to do it.”

—Natasha Gallop, above, winner of the Ms. Positivity award

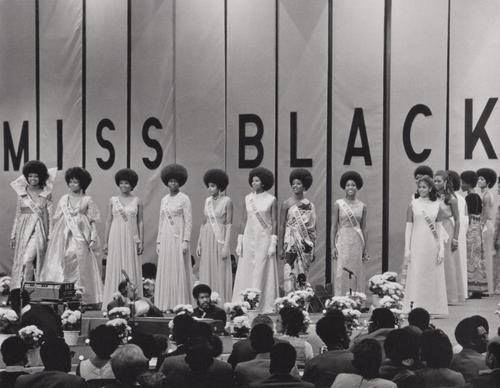

In 1967, when Philadelphia entrepreneur J. Morris Anderson asked his daughters what they wanted to be when they grew up, both answered, “Miss America.” This was, he knew, impossible. Up until 1940, the Miss America pageant barred black women from participating in the competition with rule No. 7, which said contestants must be “of the white race.” More than two decades later, a black woman had still never competed in the Miss America pageant in 1967.

Pageant stages weren’t the only platforms where black women were missing. From magazine pages to television screens to beauty ads, white women with thin bodies and straight hair dominated. The message was clear: white was beautiful; black was ugly. It was a message so pervasive that black people had begun to internalize it, says Aleta Anderson, executive producer of Miss Black America. They strove for straighter hair and smaller bodies, she says, even trying to shrink their noses with clothespins—anything to look more “beautiful.”

“We really hated our own skin,” Aleta says. “We really hated our own features.”

So when Aleta and her sister told their father they wanted to participate in a pageant that judged women by how closely they met Eurocentric beauty standards, J. Morris Anderson decided to do something about it: start a pageant that didn’t just accept but praised black women for their very blackness.

In 1968, on the same night as the Miss America pageant, the first Miss Black America pageant took place—just a few blocks away from its counterpart in Atlantic City. It began a few hours after Miss America in the hopes that, after reporters finished covering Miss America they would wander down the boardwalk to the Anderson pageant. They did, with outlets such as The New York Times covering the pageant and its first winner, Saundra Williams, who told the Times, “With my title, I can show black women that they too are beautiful.”

And now, 50 years later, 28-year-old Natasha Gallop portrays the same confidence in her body as Saundra Williams did in 1968. A short, slightly curvy woman with hazelnut-colored skin and short, natural hair, she walks across the stage calmly with an assured elegance. She’s completely comfortable with how she looks.

It took Natasha five months to get to that point of confidence. When she first started preparing for the pageant in February 2018, she caught herself thinking of ways to cover up her seeming “imperfections.”

Take her hair, for instance. She was worried about how to style it for the pageant. “My hair right now—my hair is natural—and it’s at this in-between state,” she says. It’s not a voluminous afro, but it’s not a low cut, either. “There are a lot of women, when their hair is at the length that my hair is at now, they completely put it away. They hide it.” And while there’s nothing wrong with the many styles that black women love to do, she says, she had to reflect on her inclination to hide her natural hair.

“This pageant is specifically the Miss Black America pageant,” she says. “If there is anywhere in the world that I should be loving everything about myself that is natural, this should be the place to do it.”

So she confidently embraced her natural hair. And in getting ready for the swimsuit portion of the competition, she focused on her overall health, not the shape of her waist. Natasha reflected on her worries and where they were rooted. “I wanted to make sure that the full package that I was giving to people, that everything that I was doing, encompassed what it meant to be a black woman in America,” she says.

As she and the other contestants walk across the stage for their introductions, it’s clear they have embraced the pageant’s mission, too. Slender or curvy, dark-skinned or light, natural hair or braids, everyone is tall and confident.

Three days before the Saturday night pageant, a small group mills about Kansas City’s Union Station. It’s an August morning, about 9 am, and pageant staffers are readying the room for the 10 am press conference and subsequent panel discussion. The right-side door to Union Station closes for only a few seconds at a time as staff hasten back and forth from cars to building with red carpets, black tablecloths, silver food chafers, and more in tow.

The rest of Union Station is fairly quiet. Every now and then, a business person walks through or a group of travelers wanders by, staring up at the high ceilings. There’s the occasional sound of a latte machine from the nearby cafe or the clanging utensils at Harvey’s restaurant.

Then a cheer breaks the silence. A man at Harvey’s “woos” loudly and claps. He’s looking to the far left of Union Station, where the contestants are walking in a line toward the press conference room on the right. Others look up to see why the man is cheering—23 beautiful young women dressed to the nines with perfectly styled hair and makeup—and they join in. It’s a small crowd, but their cheers echo across the cavernous station.

It’s a classic example of Kansas City hospitality.

The home of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum, the American Jazz Museum, and the Black Archives of Mid-America has embraced the pageant in its historic anniversary year. But bringing the event to the welcoming fold of Kansas City didn’t always seem likely. The year before the 50th anniversary pageant, in August 2017, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People issued a travel advisory for the state of Missouri, calling for “African American travelers, visitors, and Missourians to pay special attention and exercise extreme caution when traveling throughout the state given the series of questionable, race-based incidents occurring statewide recently.”

The advisory came a few years after racial protests in Ferguson and Columbia had attracted national media attention. So when St. Louisan Ira Fowlkes, CEO and founder of the Missouri Black Chamber of Commerce, saw an opportunity to bring the 50th anniversary pageant to Missouri and do something positive for the state, he says, he got to work.

Through the Miss Black America pageant’s partnership with the National Black Chamber of Commerce, Aleta Anderson met Ira. He told her about Kansas City’s thriving black businesses and culture and said “it would be a good thing to expose, to alert the nation to what’s going on there,” she says.

Aleta had never been to Kansas City, but as she pursued the idea, she found the city to be beautiful and full of history and its leaders gracious and welcoming. She was convinced; it was the perfect spot for the 50th anniversary pageant.

“Kansas City has so much historic programming relative specifically to people of color and with regard to American history as well,” Anderson says. “It’s just great to land in a city that obviously has growth based on this same type of passion and initiative.”

Once the decision was finalized, the city put together a planning committee, which included co-chairs Dwayne Williams and Kim Randolph and project manager Celeste Chaney-Tucker, to organize every aspect of the event.

The committee was volunteer-based, and members worked around their day jobs, sometimes in 80- to 90-hour weeks, to make the event a reality. But like Ira Fowlkes, they wanted to show the world that Kansas City welcomes all people, regardless of identity. “I think people have a lot of misconceptions about the state of Missouri,” Dwayne says, “so we want to show them here in Kansas City that all people are welcome to come and bring their events.”

That’s not to say that one black-centric event is the solution to the city’s or the state’s problems. Kansas City’s disparity in educational and economic opportunities between predominantly white areas and those in predominantly black areas is a festering point of contention among residents.

But, says Kansas City Mayor Pro Tem Scott Wagner, “Events like Miss Black America are touchstones. There are some long-standing things that we are trying to talk about and work through some plans now.” Such efforts include discussions regarding affordable housing and racial segregation and initiatives to support black-owned business and increase job opportunities for black residents.

The pageant was just a starting point in fostering inclusivity and diversity in Kansas City, Scott says. “We hope that an event like this is not an ending to those sorts of events but really a beginning of trying to provide opportunities for organizations and people to know that they can do events, they can gather in Kansas City,” he says.

There is much more work to do, but by the city’s standards, the event was a success. “The idea was to provide an opportunity for people to see what Kansas City can be and what it’s all about,” Scott says. “What we wanted to do was really use this as an opportunity to highlight the welcoming aspect of the city.”

And a welcome is what people got. Throughout the week, pageant staff, contestants and visitors spoke highly of the city. They loved its beauty, hospitality, history and, of course, barbecue. First-time visitors, such as Natasha’s mother Tuneshia Gallop from New Jersey, say they were amazed by the city’s friendliness and welcoming attitude. The city was on display, and people liked what they saw.

Soon, the Kansas City welcome will be on display for the nation, when the pageant airs on national TV. This is when the benefits of the pageant will be fully realized, Scott Wagner says. The 90-minute broadcast—airing on Black America Network and syndicated to stations across the country—is projected to reach 50 percent of households nationwide and 85 percent of black households, and will feature footage of the city’s scenery and history, further increasing and improving the city’s national image. KMBC-TV 9 will air the special in the Kansas City metro area.

“Kansas City will definitely be proud of it,” Aleta says.

It’s nearing 2 am when the pageant finally begins to wind down. The audience has dwindled since the pageant started. Because of the television taping, various portions of the pageant have been repeated once, twice, sometimes three times in the quest for the perfect take. The contestants’ swimsuit dance that inspired head-turning praise from a male audience member the first time around left him only clapping by the third performance. The audience’s applause that weakened with each take earned a reminder from the emcee to keep enthusiasm high throughout the night.

The night’s mishaps are indicative of the organization’s current rebuilding stage—its state of growth, Natasha says. “The organization has a lot of growing to do as far as traction in the media and things like that to get back to where it was when it first started,” she says.

Indeed, for a while, the Miss Black America pageant was on the rise. In its second year, the pageant took place at Madison Square Garden and featured talent such as Stevie Wonder and the Jackson 5. Later, it attracted contestants such as media mogul Oprah Winfrey and Grammy Award-winning singer Toni Braxton, and in 1977, it aired on NBC. It was a successful organization that frequently attracted media attention.

But everything changed in 1992 when boxer Mike Tyson was convicted of raping contestant Desiree Washington after a guest appearance at the 1991 Miss Black America pageant in Indianapolis. The pageant’s image suffered as a result, and in the late ’90s the organization went on hiatus for more than a decade. In 2009, the pageant returned to the stage, and has been working on rebuilding its image and participation.

It took steps toward that in 2014, when it launched a “rebirth” aimed at addressing ongoing issues in the black community, showing the need for the continuation of the pageant. The week of events for the 2018 pageant fulfilled this mission by featuring a panel discussion on mass incarceration—an issue that, in 2016, affected black people at 3½ times the rate of white people, according to the US Bureau of Justice Statistics’ jail inmates report.

But the organization still faces challenges. The pageant attracted relatively low attendance this year despite it being the 50th anniversary, and a lack of organization and communication caused some contestants to take their frustrations public. These are hurdles Aleta says every production must overcome, declaring that the organization turned those obstacles into steppingstones and produced a successful event.

There was external criticism this year when the Miss Black America pageant chose to continue including a swimsuit portion despite the Miss America Organization’s announcement last summer that it would drop its swimsuit portion and no longer judge contestants based on looks. Miss America’s decision prompted much media coverage and a call from The Kansas City Star for Miss Black America to follow suit. But the swimsuit portion, Aleta says, isn’t about looks; it’s about confidence. “It’s an opportunity to build esteem in young, black women,” she says. “It’s an opportunity to love yourself and just to have that confidence and to glow on every stage that you’re in.”

The Miss Black America organization also must answer to opponents who argue the pageant is no longer needed, given that Miss America both allows and crowns black women—arguments that have been made since the first black Miss America contestant in 1970 and the first winner in 1983.

But Aleta and others say it’s imperative that this event continue because it was created by and for black people. It judges them on their own standards, Aleta says, not ones that have slowly but not fully become less white-centric.

Miss Black America is a stage where Philadelphia contestant Seraiah Frazer receives extra-loud cheers for wearing her hair in a full, voluminous afro. It’s a stage where Khadija Lamah, whose parents are from Liberia, makes the top 10 in talent for her monologue on her multifaceted black identity. It’s a stage where, at the end of her performance of This Is Me, Natasha Gallop says, “In a world that tries to constrain and confine you for your very blackness, I need you to be unapologetically yourself because it’s enough” and is out-cheered only when she lifts her fist in the air. It’s a stage where every contestant, no matter her body type, skin color, or hairstyle, is celebrated for who she is.

Which is why, for all its challenges, Aleta considers the 2018 pageant a success. Because at the end of the night, there’s yet another Miss Black America—Ryann Richardson of New York. A successful entrepreneur and tech marketer, Ryann will spend the year advocating for women and people of color. She’ll aim to increase black women’s presence in the technology industry. She’ll continue pushing diversity and inclusion initiatives.

But most importantly, she’ll be a role model for the black community, a manifestation 50 years in the making of Natasha Gallop’s message that black people can be unapologetically themselves because it’s enough.

Related Posts

Don’t Miss Your Last Chance to See The Elders

This year marks the band’s 20th anniversary of playing together, but the members of the powerhouse Irish/ Celtic band recently announced that 2018 will be the last year they plan to perform together—at least for the foreseeable future.

Inside the Newest Cafe & Bike Shop on the Katy Trail

Closely nuzzled against the Katy Trail in Rocheport, Meriwether Café & Bike Shop provides a quietly colorful experience. Managers Brandon and Whitney Vair transformed the building that used to house the Trailside Café into a bright spot set against the green-covered hills of Rocheport.