Based on eyewitness accounts and geological evidence, seismologists estimate the New Madrid earthquake to have been 8.0 on today’s Richter scale. The shock waves were felt from the East Coast to the Rocky Mountains, and from southern Canada to northern Mexico.

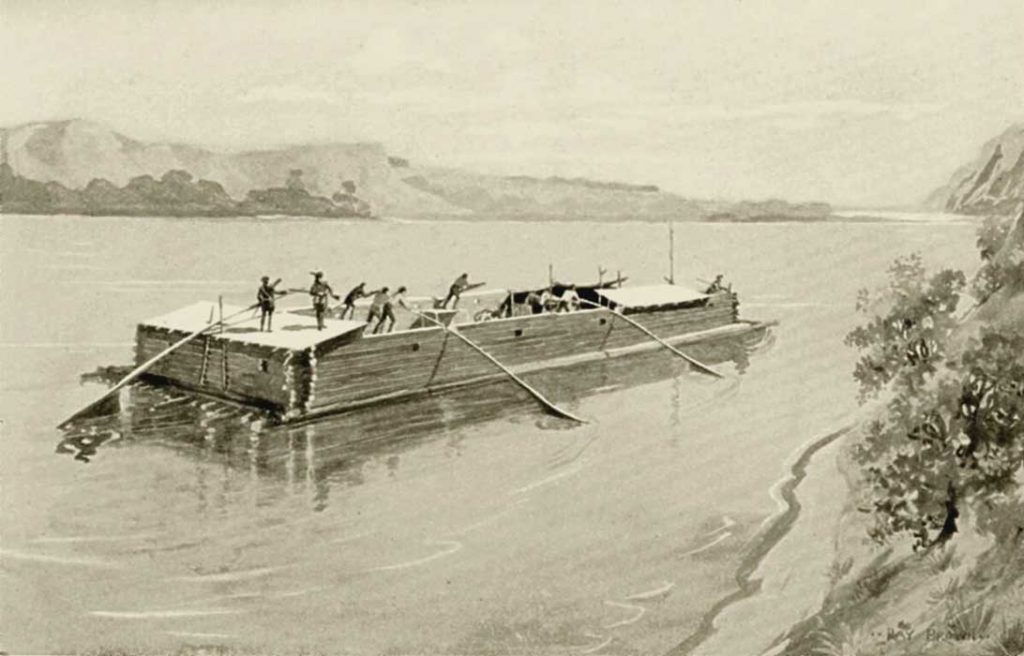

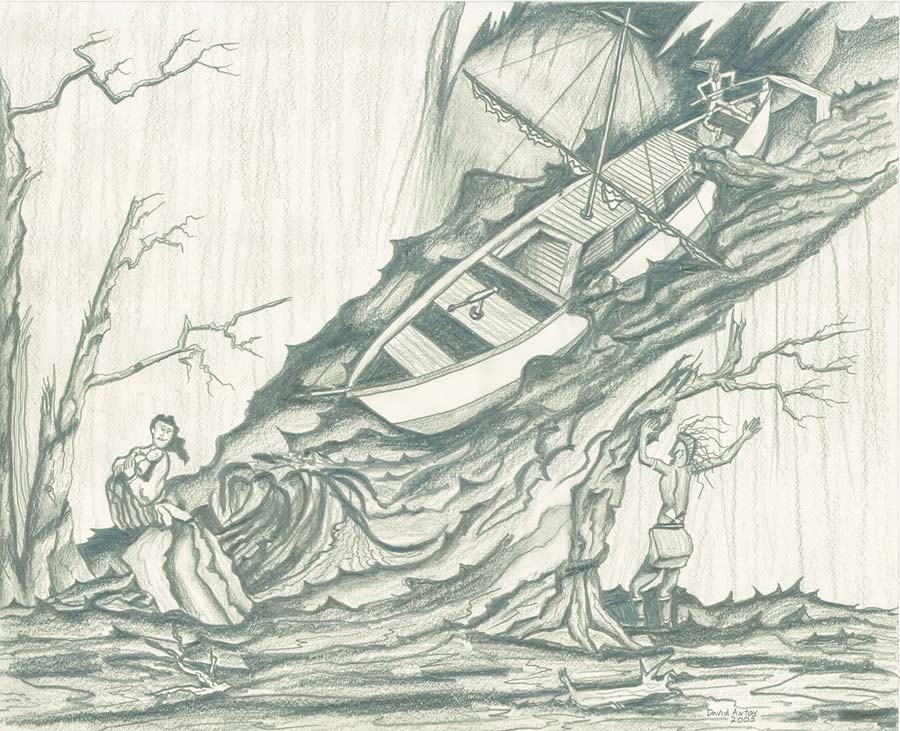

On December 15, 1811, William Pierce was traveling the rivers of the West in a flat-bottomed boat, about 116 miles below the mouth of the Ohio River and just south of New Madrid. The evening was unpleasant—“dark and cloudy,” Pierce recalled, “and the weather unusually thick and hazy.” Suddenly, the world erupted under and around him. In a letter to the New York Evening Post, he wrote, “Everywhere Nature itself seem tottering on the verge of dissolution.”

As Pierce and his traveling companions watched, the earth opened up before them, sending “a volcanic discharge of combustible matter” skyward. “The earth, river, etc., torn with furious convulsions, opened in huge trenches. There through a thousand vents sulphurous streams gushed from its very bowels leaving vast and almost unfathomable caverns,” wrote Pierce. The travelers found no haven in the river. “The bed of the river, was excessively agitated, whilst the water assumed a turbid and boiling appearance. Never was a scene more replete with terrific threatenings of death.”

Based on eyewitness accounts and geological evidence, seismologists estimate the groundbreaking earthquake to have been 8.0 on today’s Richter scale. The shock waves were felt from the East Coast to the Rocky Mountains, and from southern Canada to northern Mexico. Following along like malevolent handmaidens, some 2,000 aftershocks ensued.

The December 15 earthquake was merely the first of five major quakes and hundreds of tremors that ravaged the southeast Missouri landscape for three months.

One regional historian described the seismic event as “the most violent earthquake that ever happened within the recorded history of humans on the North American continent.” Although many people think of California’s San Andreas fault, which birthed the San Francisco earthquake of 1906, as the most dangerous in North America, the quakes from 1811 to 1812 that erupted from the New Madrid Seismic Zone were the most destructive. The fault line runs some 150 miles from Marked Tree, Arkansas, to Cairo, Illinois, passing through southeast Missouri.

The series of disruptions that history has singularly dubbed the New Madrid Earthquake left their marks on more than two dozen states and territories. Several towns were destroyed; some had disappeared before the earth calmed several months after the first quake hit in 1811. Rivers changed course. The few survivors from the area were homeless, their communities scattered. The people living in the area filled churches, seeking reprieve from God’s wreckage of the earth.

A Cove of Fat

Established as a trading community on the Mississippi River in the southeastern corner of what is now Missouri, the site of New Madrid had been a prime location for local tribes long before the coming of the Europeans. Game was plentiful, and when the French arrived in the 17th century, they named the area L’Anse a la Graisse—cove of fat, or grease—for its profusion of bear, bison, elk, and antelope.

The American iteration known as New Madrid was laid out in 1789 by the speculator, Revolutionary War veteran, and Indian trader George Morgan. The location seemed ideal for farming as well as fur trading because the land sat higher than that around it, ostensibly protected from river flooding. It would not be long before the settlers would witness firsthand just what type of cataclysm had long ago elevated the site.

For years after the establishment of New Madrid, the settlers—French, British, and American—lived in their log and frame houses in relative security. By winter 1811, the bulk of the season’s work was done; the crops had been harvested, and supplies of food and stores of firewood had been laid in for the winter.

Then, in the middle of the night of December 15, residents awoke to thunderous roars that reverberated like cannon fire. Houses began to shudder and move. Furniture slid across floors, brick chimneys collapsed, and heavy logs screeched as they skidded against one another. Everyone in the community rushed out into the winter night, to be met with the overpowering stench of sulfur.

In the bitter cold, the settlers remained outdoors throughout the night, as the temblors renewed every few minutes. The earth’s emanations of smoke, water, dirt, and steam, amid an overpowering sulfurous stench, blocked the view of the moon and stars as a cacophony of terrified animal sounds and the roar of the quake engulfed the stunned community standing in near-total darkness.

Resident schoolteacher Eliza Bryan painted a vivid image of people running aimlessly in the dark, while around them “the earth was horribly torn to pieces.” Recalled one settler: “The night (was) made loud with the cries of fowls and animals, the cracking of the trees, and the surging torrent of the Mississippi.”

earthquake (December 16). The boat reached the Mississippi on December 18 and passed New Madrid, Point Pleasant, and Little Prairie (the epicenter of the quakes) on December 19. They spent the night near the mouth of the St. Francis on December 22, where they learned about the disappearance of the steamboat Big Prairie, which was also descending

the river at this time.

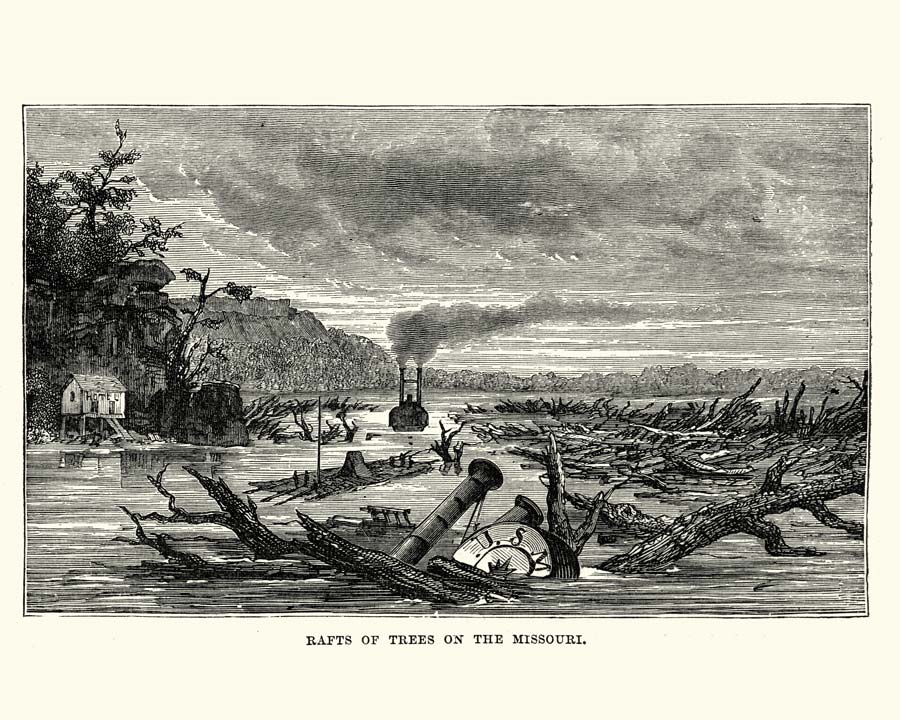

The lower Mississippi River was indeed roaring and roiling along its length in high, violent waves that collapsed its banks, swept forests into the water, and claimed countless boats, along with their hapless crews and passengers. A British naturalist traveling by keelboat was spared. “The banks above, below, and around us,” he later wrote, “were falling every moment into the river, all nature seemed running into chaos.” Some witnesses claimed that, for a short time, the river ran backward.

Around 7 am December 16, another quake struck, every bit as powerful as the first. By this time, the air had filled with fog and the vapors spewed from within the earth. As the settlers watched, the ground bucked and rolled, opening fissures that spit rocks and sand high into the air. An inescapable vision of hell had descended upon New Madrid, and there was no place to hide.

Four hours later, a third quake rolled through—the strongest yet. The nucleus of this megaquake emanated from the town of Little Prairie (now Caruthersville), south of New Madrid.

That night, Little Prairie residents abandoned their homes. Unaware that New Madrid had been devastated by the same natural disaster, the refugees set out on foot for the 30-odd-mile journey to New Madrid. The clearly marked trail was no more, beset with crevasses and fissures, felled trees, and newly made quicksand bogs with muddy water that went from shallow to deep without warning. The settlers dodged panicked snakes and other creatures desperately seeking safety—as were the settlers—from the unpredictable toil.

Pervading everything was the sickening pall of sulfur.

It was a daylong journey. When the travelers from Little Prairie arrived on Christmas Eve at what was left of the once-busy market town that had been New Madrid, they saw the same devastation they had left behind. None of New Madrid’s residents remained; most were camped in the woods a couple of miles outside of town, the skewed and twisted ruins of their homes, barns, and shops left behind.

New Madrid may have been decimated, but it offered more than Little Prairie, whose refugees had no town to return to; the second quake had virtually leveled Little Prairie when it ripped off the entire river bank, dropping it into the foaming, turbulent river. With nothing to hold back the water, the town and surrounding countryside for miles flooded to a depth of three to four feet.

whiskey before the Revolution. During the great migration of settlers west of the Appalachians after 1873, they may have also carried salted pork and tobacco to early pioneers. This appeared in Western Rivermen, 1763-1861: Ohio and Mississippi Boatmen and the Myth of the Alligator Horse, by Michael Allen.

No Reprieve

Minor eruptions continued to shake the earth for weeks, and on January 23, a fourth major quake hit the New Madrid area. Traveling south from St. Louis, Arkansas engineer and surveyor Louis Bringier witnessed it, recording a description a few months later. “The roaring and whistling of the air escaping (from the earth) seemed to increase the horrible disorder of the trees blown up, cracking and splitting and falling by thousands at a time,” he wrote. “In the mean time, the surface was sinking and a black liquid was rising up to the belly of my horse, who stood motionless, struck with a panic of terror.”

Many thought they had seen the worst of the quakes. Two weeks later, at 4 in the morning of February 7, a fifth quake struck, the largest yet. Those who had dared return to their damaged homes watched the earth split in seemingly endless lines of fissures, each running southwest to northeast, hundreds of feet or more in length, and deep enough to swallow livestock. One crack split the earth for a distance of five miles. And through it all, the ground continued to pitch and roll, a stomach-churning motion that threw people about like rag dolls.

With this fifth quake, the Mississippi River outdid itself. The water rose 20 feet above its normal level in some places, overflowing and collapsing its banks. As the schoolteacher Eliza Bryan watched, it “seemed to recede from its banks, and its water gathered up like a mountain, leaving … boats stranded on the sand.” Beached crews ran for their lives as the river crashed upon them and their vessels. The riverbed split and cracked into the same fissures as were occurring on land, causing the water to boil and form whirlpools and geysers.

Two waterfalls appeared on the river, a mile from New Madrid. Although they existed for only a brief interval, they were lethal; 30 boats went over the New Madrid falls, and 28 of them sank. Most of the crew members of the doomed vessels drowned. Another 19 boats tied to the New Madrid docks were ripped from their moorings and swept to destruction. The wreckage of vessels was everywhere.

The months-long New Madrid earthquakes left their mark upon the land and the water. By the time the quakes had subsided, the landscape had undergone a radical makeover. Islands had vanished from the Mississippi River; five entire towns in three states had simply disappeared; lakes had suddenly appeared overnight, in some cases swamping forests. The quakes had affected more than one million square miles—more than 16 times the area stricken by the famous San Francisco earthquake of 1906.

Many lost their lives during the months in which the quakes deviled the region, yet there are no accurate records to help estimate the number of fatalities. According to New Madrid historian Norma Hayes Bagnall, “It is assumed that most deaths resulting from the New Madrid earthquakes were caused by drowning.” By March 1812, few people remained in the area. A quarter century later, just 450 people lived in New Madrid. Only gradually did it reclaim its place as a viable river port town. “It was a long time,” writes Bagnall, “before the people and the land in southeastern Missouri healed.”

1811-12, for an original look at the devastating earthquakes in the book, New Madrid: A Mississippi River Town in History and Legend, published by Southeast Missouri State University Press in 2009).

End of Days

Those who survived coming face-to-face with a disaster of biblical proportions sought answers. Not surprisingly, the people who had witnessed the quakes firsthand—as well as countless thousands who had merely heard or read the accounts—saw in them the sign of divine intervention, an indication of God’s dissatisfaction with humankind. As the hymn “A Call to the People of Louisiana,” penned months after the quakes, proclaimed:

More than six months have

past and gone,

And still the earth keeps shaking;

The Christians go with

bow’d down heads,

While sinners’ hearts are aching.

The great event I cannot tell,

Nor what the Lord is doing;

But one thing I am well assur’d,

The scriptures are fulfilling.

Adding to the fear of divine disaffection was another natural phenomenon that occurred several months before the earthquakes. In March 1811, a comet appeared and remained visible for 260 days (a record not broken until the Hale-Bopp comet of 1997), revealing a coma—the luminous cloud surrounding the nucleus in the head of a comet—that was purportedly one million miles long, or 50 percent larger than the sun. Known to history as the Great Comet of 1811, it has also been called Napoleon’s Comet, believed to have presaged the emperor’s ill-fated invasion of Russia.

With the comet still visible when the earthquakes began, the doomsayers had considerable clout. “Earthquake Christians,” as they came to be called, suddenly sought to get right with God, and membership in the local Methodist and Baptist churches soared. According to historian David W. Fletcher, “Preachers attested significant numbers of baptisms and conversions, since sinners wanted to avoid further outpourings of God’s wrath.” As one minister recalled, “It was a time of great terror for sinners.”

In many cases, the ferver didn’t last. “A good number of these new believers turned away from the church once the earthquakes subsided,” Fletcher found.

Human nature being what it is, once the immediate threat of destruction had passed, the prophets of the end of days found themselves addressing ever-smaller crowds. The earth gradually settled into a more tranquil if somewhat altered state.

From time to time over the past two centuries, there have been prophesies of another cataclysm from the fault line that runs deep beneath our feet. Notably, on September 26, 1990, the earth shook in the tiny city of New Madrid, caused by a relatively small earthquake.

Since then, the fault line has remained still.

The city’s population, which hovers around 3,000, tends to look at the geological possibilities philosophically. One observer sums up the town’s combination of caution and inevitability: “Its citizens … keep one eye on the Mississippi and one eye on the hills.” New Madrid folk singer Lou Hobbs put it another way in his signature song, “Living on the New Madrid Fault Line”:

The good Lord, He put us all here

And only He’s gonna take us away.

Living on the New Madrid fault line,

You gotta live it day by day.

Article originally published in the February/March 2018 issue of Missouri Life.

Related Posts

March 20, 1811

Birthday of perhaps Missouri's greatest artist, George Caleb Bingham from Franklin, Arrow Rock, and St. Louis, MO. Read more about this in Tales From Missouri and the Heartland.

December 16, 1811

The first shocks occurred in the largest earthquake ever to shake North America. It was centered on the New Madrid Fault in Missouri. Read More about this in Tales From Missouri and the Heartland.

April 19, 1812

James S. Rollins was born on this day. Many recognize Rollins as the Father of the University of Missouri.