With great trepidation, our writer faced the uncomfortable emotional and physical challenge of sleeping in a slave cabin in Missouri’s Little Dixie, with a pounding rain on a tin roof, no less. Find out what she experienced and learned.

When I was a little girl, my grandparents bought me a doll named Addy Walker. She was part of the Historical Characters line in the American Girl Collection. Addy came with a series of six books about her experiences as a 9-year-old slave in 1864 who escaped with her mother to Philadelphia after their master sold Addy’s father and brother to another plantation. I devoured those books and carried her everywhere with me. My beloved Addy offered me a window into a part of history that seemed far removed from my own life until then. Even at a young age, it wasn’t difficult for me to envision how my life could have been similar to hers had I been born just 130 years earlier. It was my first experience of how powerful history can be when it’s not confined to a page or a movie screen.

Sixteen years removed from Addy, the chance to participate in an overnight visit to a slave cabin offered me another opportunity to connect to this aspect of our history. When I was approached with the offer to write this article, I had a variety of emotions. I was excited and intrigued about what it would be like. But I was also nervous and even a little scared about the uncomfortable emotional and physical environment that I might encounter.

Prior to my trip to the slave cabin, I reflected on my knowledge of slavery in the United States. The topic had been part of my high school education, and of course, I’d seen movies such as Roots and The Color Purple. I even vaguely recalled a childhood family vacation that had included a tour of Harper’s Ferry, West Virginia, where abolitionist John Brown raided the town’s arsenal with a group of 21 men to get weapons for a slave uprising in 1859.

However, it wasn’t until college that I really received an extensive education on slavery. As a student at the University of Missouri, I took a course on the history of the Old South. It was so compelling and in-depth, that I signed up for a course on the New South taught by the same professor the following semester. It was the first time that I’d ever been introduced to the various political, social, and economic factors at play during slavery. The nuances were fascinating to me, and they painted a much more dynamic picture of the realities of slavery than I had ever known before.

The courses made me disappointed that the topic had been presented to me previously in such a generic, watered-down fashion. After college, I took a trip to my grandfather’s hometown of Natchitoches, Louisiana. There are several plantations in the area, and I was able to tour Oakland Plantation, a National Historic Landmark, which still has 17 of its original outbuildings remaining including slave cabins.

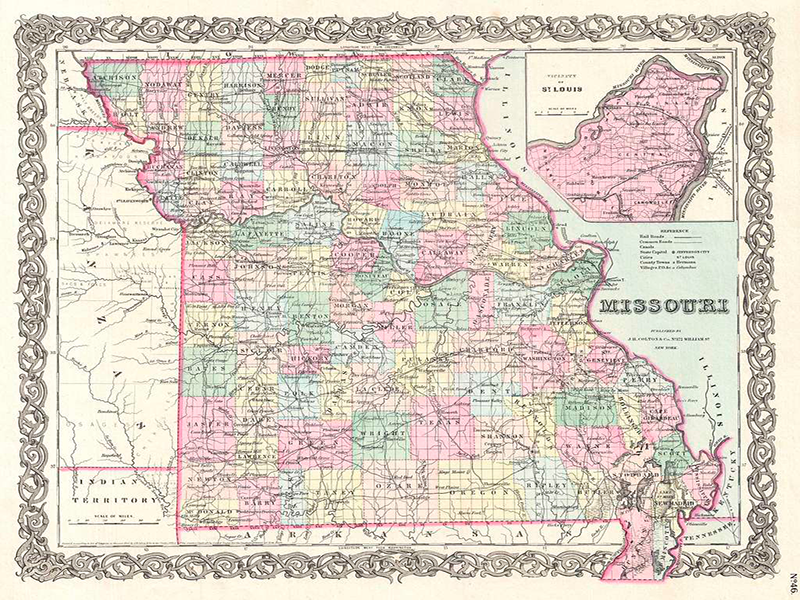

With this background, this past summer I visited Missouri’s Little Dixie region, which is comprised of 17 central Missouri counties. The area includes all the counties along the Missouri River going east from Kansas City to Callaway County and then further east to St. Louis and on the north to Pike County on the Mississippi River. Gary Gene Fuenfhausen, president of the Little Dixie Heritage Foundation, says the territory was so saturated with slave labor by 1860 that it mirrored the social, economic, and cultural climate of the upper south portion of the United States.

My first stop in Little Dixie was the Pleasant Green Plantation in Pilot Grove. Established in 1818 by Anthony Winston Walker, his wife Polly Rubey, and their three sons, the family had two slaves when they arrived in Pilot Grove from Virginia. By 1840, they had five slaves. I arrived on a Friday evening and had dinner in the main house with plantation owner Florence “Winky” Chesnutt and her guests Vicki McCarrell, the owner of the Burwood Plantation in Pilot Grove, Gary, and David Lerch, a partner with Gary in the Little Dixie Heritage Foundation.

After dinner, I retreated to the double room slave quarters situated around 50 to 75 feet away from the main residence in the backyard. In the late 1800s, five such cabins existed at Pleasant Green before they were burned down or removed in the 1900s. Gary says the quarters were so close to the main house because owning slaves was a sign of wealth and the masters wanted to be able to show off to visitors the people whom they considered prized possessions. The cabin has since been updated with some modern amenities such as electricity, indoor plumbing, and new flooring, but I learned the original layout would have included a three-top stove, coal-oil heater, a rope bed with a corn-husk mattress, wood floors, and a small wooden table that could seat four. There was also a chamber pot that could be used in lieu of the outhouse which still stands on the property.

Both rooms of the cabin were the size of my college dorm room or a studio apartment but would have been expected to house an entire family. Although they were modest, I was surprised to find the accommodations were far better than I had expected. Gary later told me that the quality of life presented to slaves was a direct reflection of how their masters felt about them. The experience of slavery differed from one plantation to the next. Some slaves were forced to eat their meals out of pig troughs while others were treated more like members of the master’s family. Slave quarters could consist of one cabin or multiple cabins depending on the wealth of the plantation owner. Some plantations in places like Callaway County housed four or five slaves per building. Other owners, who depended on revenue from cash crops in places like Saline County, would house 10 to 20 slaves in one cabin. Some masters gave their slaves autonomy within their cabins while others checked the slave quarters every night and retained control over the space.

Even after they were freed, the slave hands who worked at Pleasant Green chose to remain in the quadrangle of cabins behind the main house. A newspaper report from 1918 tells of the “touching scene” of the mourning of the former slaves and their families at the funeral of Anthony Addison Walker. These two anecdotes lend clues to the type of relationship that the Walkers perhaps had with their slaves.

During my night in the cabin, I tried to imagine what the slaves who occupied the space must have felt as they ate, slept, and attempted to make a home in the shadows of their oppressors. In some ways, the cabin was their only refuge from the harsh realities of their daily lives. It was their home, but also their prison cell. In fact, the rooms of the cabins were sometimes referred to as pens.

As I struggled to fall asleep that night, many questions raced through my head. Did they use this space to plot their escape? To secretly learn to read and write despite the brutal consequences of such an act? To bond as much as they could as a family and a community. Regardless of how well they might have been treated by their owners, they were still unjustly imprisoned individuals that had to make the best of a life that was forced upon them.

In the morning, I had breakfast with Winky. She told me her memories of the plantation. Her mother Florence Cox, a fifth-generation descendant of the Walker family, purchased it in 1968 and began its restoration. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1976. Winky remains at Pleasant Green because the property and the preservation of its history meant so much to her mother. She now uses one room of the slave cabin as an art studio. She says that she and other members of her family have slept in the slave cabin overnight on several occasions.

The day continued with a tour of Little Dixie led by Gary, who has researched the area’s slave cabins since the late 1980s. Census records indicate that 60,311 slaves lived in 13,300 slave houses in Little Dixie in 1860. Today, Gary says, only 130 of those slave quarters remain. Several cabins have been torn down by those who did not understand their significance. Gary started the Little Dixie Heritage Foundation in 2010 to promote the preservation of the region’s slave cabins and to promote education about the history of the structures and their occupants.

The first stop on our tour was Crestmead Plantation, located south of Pilot Grove. The plantation is owned by Ann Betteridge and her husband Bob. Only one of the four original slave cabins remains at Crestmead: a one-room structure with two windows. It was constructed of wood board and includes a loft where children might have slept. When it was in use, the cabin would have been outfitted with a dry sink, table, chairs, and a rope bed with a corn husk mattress. A total of 19 slaves were housed at Crestmead. We traveled on to Boonville to look at examples of urban slave dwellings located in densely populated areas instead of rural environments. One such building, owned by Boonville doctor Robert D. Perry in the 1850s and ’60s, was made of brick and had two stories. It was connected to the main home by a covered walkway, and it functioned as both slave quarters and a summer kitchen.

By early evening, we were back in Pilot Grove for dinner at Burwood Plantation, built in the 1880s by Henry Ruby Walker. The homestead features one multi-room barrack-style slave dwelling at the back of the house. Gary says that this style of living quarters made it easy for slave owners to keep track of their slaves because they all lived in one building. The barracks made me think of the shed in my own backyard. It is a handy place to keep tools and other supplies, but it’s hard to stomach the idea of living there against my will.

Before going to the big house for dinner, I sat alone on the covered porch of the Burwood slave barracks as rain poured down heavily on the tin roof. I wanted to reflect on the day and night that I spent attempting to fathom the history of the slaves of Little Dixie. I realized there was no way that I could fully comprehend the horrible suffering they had endured on a daily basis. All I could do was acknowledge their trials and respect how their incredible endurance of hardship made possible the life that I’m able to enjoy today. I imagine if the walls of these slave cabins could talk, they would have astounding stories to tell. Perhaps they would be stories of despair and fear mingled with hopefulness for a better day that the slaves wanted for themselves and future generations.

The cabins are more than just pieces of architecture. They are critical relics that symbolize a dark and ugly past in both American and Missouri histories. These buildings should be preserved so the stories of the slaves that inhabited them can continue to be honored, lived, and breathed.

For more information on these slave cabins and on Missouri’s Little Dixie Heritage Foundation, visit its Facebook page of the same name.

This article was originally published in the February 2012 issue of Missouri Life.

Winky Chestnutt has since passed away.

See the pilot episode (produced in early 2015) of Missouri Life TV, where we interviewed Little Dixie historian Gary Fuenfhausen and writer Porcshe Moran about her experience at one of the slave cabins, here. This segment begins at about minute 9:51.

Related Posts

Missouri Synod was Founded

On February 8, 1839, on Missouri Synod of the Lutheran Church was founded.

Missouri Counties Formed

On January 2, 1833, new Missouri counties, including Carroll, Clinton, Greene, and Lewis, were formed on this date.

108 Missouri Wineries

On December 11, 2012, state officials announced that there were now one hundred and eight commercial wineries operating in Missouri.