The story of fugitive slave William Wells Brown, the first Black author published in America.

“O master, let me stay to catch My baby’s sobbing breath, His little glassy eye to watch, And smooth his limbs in death, And cover him with grass and leaf, Beneath the large oak tree: It is not sullenness, but grief—O, master, pity me! ••••• Then give me but one little hour—O! Do not lash me so! One little hour–one little hourAnd gratefully I’ll go.”– William Wells Brown

It’s a hot, humid August day in 1832. A group of slaves kick up dust on a dirt road shaded by large oak trees outside of St. Charles. Failing to have caught a boat on time, the slave trader and his slaves travel on foot toward the city of St. Louis—a 23-mile journey. William Wells Brown is one of these slaves.

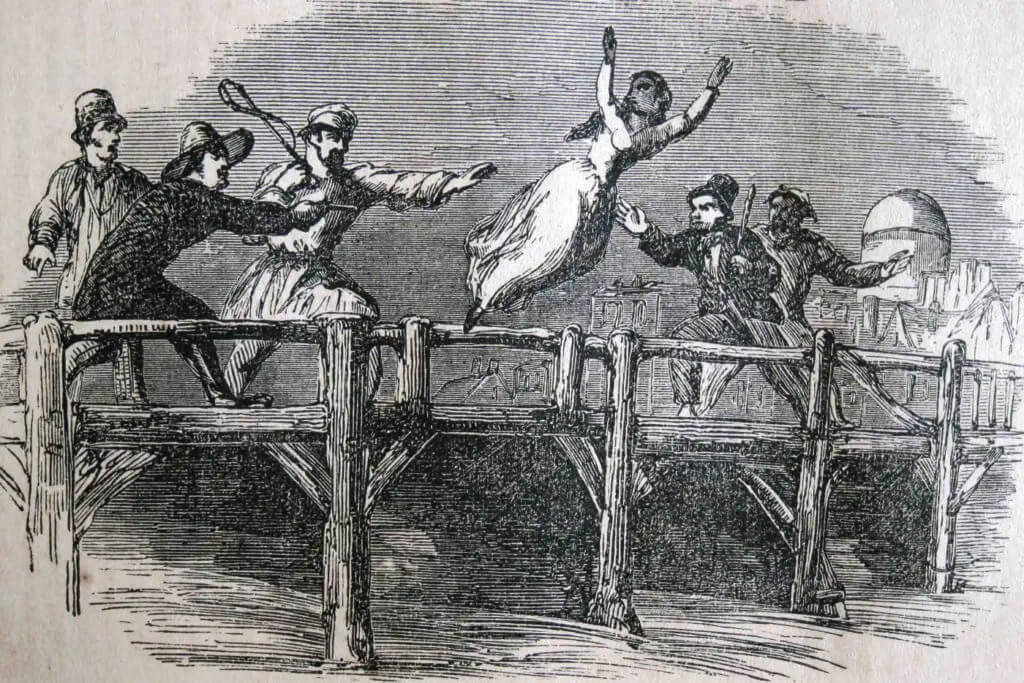

Their chains clink together rhythmically, a solemn elegy for freedom. A four-week-old infant cries; his wails of discomfort continue for hours upon end with no relief. His White master tells the mother to quiet the child, and her eyes widen in fear. She clings to her child trying desperately to soothe him, but the baby continues to wail.

The master suddenly grabs the child, carrying it away by one arm. He gives the baby to a White woman standing beside the road. “It keeps such a noise that I can’t bear it,” he growls. Dropping to her knees, the slave mother begs to keep her child. With no compassion from her master, she is chained to the line of slaves and forced to walk on, never to see her child again. Chains clang on down the dusty road, and the heat of the mother’s sobs mixes with the fiery heat of a Missouri August.

Fifteen years after experiencing this moment, William recounted the horror he witnessed as a slave in his first published book: The Narrative of William W. Brown, A Fugitive Slave. The desperation of the slave mother and the cries of her infant child would forever haunt him.

The distribution of William’s true stories were groundbreaking for American society. Words like these had never come from the pen of a Black author before. In the 1800s, slaves were banned from learning to read or write, as White slave owners feared that their education would lead to rebellion. Fines for teaching a Black person to read or write ranged from $7,000 to $16,500 in today’s money. This didn’t stop William from learning to write and telling his story. He became a freedman, published author, and playwright by the age of 30.

The road to “sweet freedom’s plains,” as William fondly called his final destination to freedom, was excruciatingly dark. If met with the obstacles he faced, many would have given up. His mental fortitude and courage, along with a few friends, were what made William’s freedom possible.

William Begins His Journey to Freedom

William Wells Brown was born into slavery in Lexington, Kentucky, to his enslaved Black mother, Elizabeth, and free White father, George Higgins. A short time after he was born, his father died, and he and his mother were sold and moved to St. Louis to work on a tobacco and hemp plantation.

As William grew into his teenage years, he was “hired out” by his master John Young (often referred to as Dr. Young) and was forced to work on steamboats, tend crops, drive carriages, run a press, and manage homes all around the city of St. Louis.

William’s first stop on his journey to freedom was a public house—a restaurant and boarding house for travelers— owned by the well-known St. Louisan Major Freeland, who rented William from John Young to work there. Major Freeland was “a horse-racer, cock-fighter, gambler, and inveterate drunkard,” according to William.

The crew of ten to twelve servants running the public house only felt at ease when their master wasn’t home. When Major Freeland was present, there would be chairs f lying through the air, angry screaming, and whipping, and he would implement his “Virginia play”: leaving servants tied upside down in the smokehouse with tobacco stem fires burning. After six months of witnessing and enduring this treatment, William asked Dr. Young for a different placement. “He cared nothing about it, so long as he received the money for my labor,” William said. Out of options and anxious for a reprieve, William tried to escape, running from the public house to the woods.

William’s attempted escape instantaneously took a turn for the worse. “While in the woods, I heard the barking and howling of dogs, and in a short time they came so near, that I knew them to be the bloodhounds of Major Benjamin O’Fallon. As soon as I was convinced that it was them, I knew there was no chance of escape,” William wrote.

He climbed a tree to try and throw off the scent of the dogs, but eventually, William was found. The men ordered him to come down and took him to the St. Louis jail. After his release, he was beaten severely by Major Freeland for his attempted escape.

Soon after these events, Major Freeland’s business fell into bankruptcy, and Dr. Young placed William on the steamboat Missouri, which ran from St. Louis to Galena, Illinois. Under his master William B. Culver, William’s time on the steamboat was “the most pleasant time for me that I had ever experienced,” William recounted.

Though his time on the steamboat Missouri was good, it was also short. After a single sailing season, William was sent into the hands of John Colburn—the worst master he would encounter during his lifetime.

Regardless of the easier work, the home was meticulously run six days a week, and William was always being watched. Instead of being able to rest on Sundays and f ish, basket weave, or the like, every slave was required to attend religious meetings and worship from morning to night. As difficult as this time was, it was only a foretaste of the struggle that William was about to undertake during his second stint on the steamboat Enterprize.

John Colburn was a violent man. He was “very abusive, not only to the servants, but to his wife also, who was an excellent woman, and one from whom I never knew a servant to receive a harsh word; but never did I know a kind one to a servant from her husband,” said William.

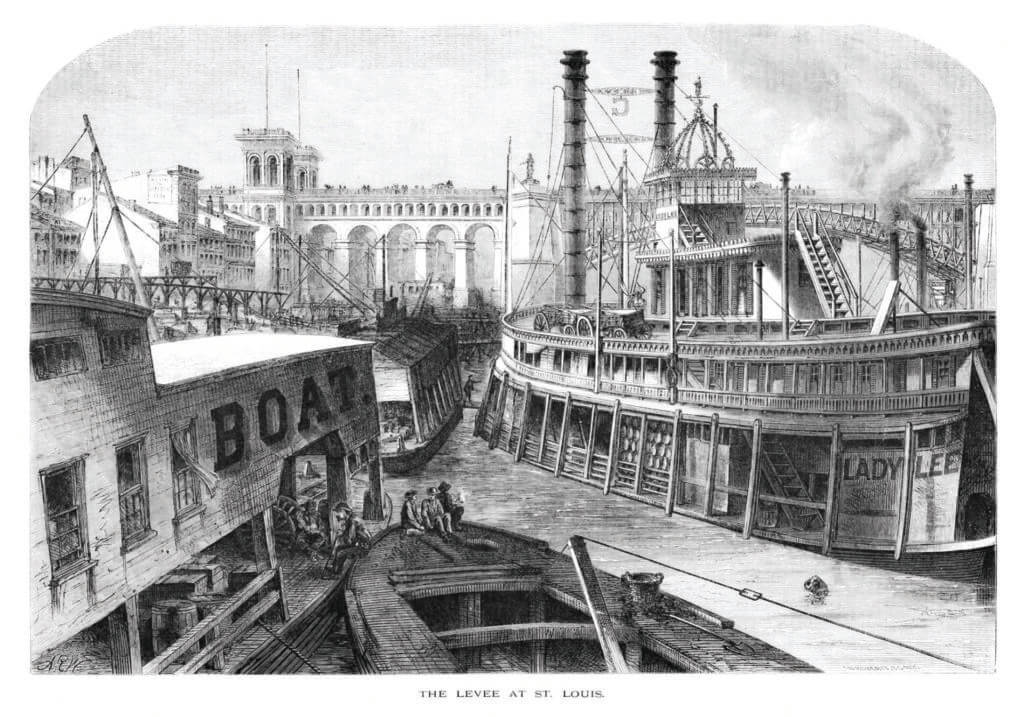

Conditions were so severe that one slave by the name of Aaron was given over fifty lashes with a cowhide rope after leaving a small spot on a silver knife he was cleaning. William was then forced by John Colburn to pour rum on his comrade’s lacerations. The alcohol burning Aaron’s open wounds seemed worse than the The levee at St. Louis whipping itself. Aaron was returned to his original master and asked for a transfer, which was denied. John Colburn caught word of this and whipped Aaron “even more severely than before,” William said. Aaron’s condition was so bad that “the poor fellow’s back was literally cut to pieces,” said William. Aaron was unable to work for ten to twelve days due to the state of his wounds.

After enduring excruciating circumstances under the hand of John Colburn, William was transferred to the St. Louis Times under the supervision of Elijah P. Lovejoy. Elijah was the editor and publisher of the St. Louis Times, and William spoke highly of him in many regards. “Mr. Lovejoy was a very good man, and decidedly the best master that I had ever had. I am chiefly indebted to him,” William wrote, recalling that much of his early learning with reading and writing was attained while working there.

African American studies professor Patrick F. Ryan at Hilbert College in Buffalo, New York, adds, “This was [William’s] first time seeing antislavery papers, and Lovejoy did help him learn. Elijah went on to be a noted abolitionist.” At only 35 years old, Elijah’s print shop was burned to the ground, and he was murdered by a proslavery mob.

While working at the Times, William ran the press and served the staff. He also ran errands to the Missouri Republican, run by Edward Charles. One of these trips almost ended his life.

Several of the sons of local slave owners attacked William one day on his journey to the Missouri Republican office. They pelted him with their fists, snow, stones, and sticks. He did his best to fight back and defend his life, barely making it back to Elijah’s office. One of the boys’ fathers, called Mr. McKinney, claimed William had “hurt his boy.” The father found William, took him by the collar, and struck him over the head with a cane over and over “in such a manner that my clothes were completely saturated with blood,” William recalled. After seeing his condition, Elijah sent William back to his owner John Young’s plantation to recuperate. It was five weeks before William could walk again. To his dismay, William was informed that he had lost his position with the St. Louis Times and had been transferred.

Serving and waiting tables became William’s everyday task under Captain Otis Reynolds on the steamboat Enterprize. He described the captain as being a “good man” and the situation as pleasant. But no matter how pleasant the environment, freedom was still a sweeter dream. “In passing from place to place, and seeing new faces every day, and knowing they could go where they pleased, I soon became unhappy,” William said.

Memories of William’s beloved mother describing being beaten and whipped for sneaking out of the fields in Kentucky to nurse him kept him from jumping into the rapid waters and attempting an escape to Canada to seek freedom. “I would resolve never to leave the land of slavery without my mother. She had undergone and suffered so much for me,” William wrote.

Soon Captain Otis left his position on the steamboat Enterprize, and William was sent back to John Young’s plantation. Under overseer Friend Haskell, he was put into the fields to harvest corn, and he recalled with exasperation, “I found a great difference between the work in a steamboat cabin and that in a corn field.” He was soon ordered to work in the house as a waiter, an easier job than a field hand and a more forgiving one.

Regardless of the easier work, the home was meticulously run six days a week, and William was always being watched. Instead of being able to rest on Sundays and fish, basket weave, or the like, every slave was required to attend religious meetings and worship from morning to night. As difficult as this time was, it was only a foretaste of the struggle that William was about to undertake during his second stint on the steamboat Enterprize.

One of William’s most emotionally taxing jobs was when he worked once again on the steamboat Enterprize. Being hired by a slave trader, called Mr. Walker, William was assigned to a term of one year as a soul-driver: a slave forced to enchain and sell other slaves, oftentimes tearing apart husband and wife or children from their mothers. “When I learned the fact of my having been hired to a ‘soul-driver,’ no one can tell my emotions,” William explained.

He tried his best to provide comfort to the other slaves, but it was almost an impossible task. Slaves were placed in a slave pen and were chained together. This space was “impossible to keep,” William recalled. His jobs were numerous and odd, such as plucking gray whiskers from the chins of old men or dying the slaves’ hair black with polish to make them appear years younger.

William was forced to make the captive slaves sing, dance, jump, and play cards in the sale yard while tears slid down their faces. They were made to act “lively” while being inspected by White slave owners who frequently took them away from everyone they loved. This was its own form of imprisonment for William and made him “heart-sick at seeing fellow creatures bought and sold.”

While enslaved as a soul-driver, William was forced to partake in the slave trade firsthand. He experienced suicides, beatings, families being torn apart, and unsanitary conditions. One of his worst experiences as a souldriver—as commemorated in one of his poems—was when William’s master, Mr. Walker, took a crying infant from his slave mother, “gifting” it to a White woman housed nearby to get rid of its “damned noise.”

Eventually, William’s year as a soul-driver ended and he was able to return home. “After selling out this cargo of human flesh, we returned to St. Louis, and my time was up with Mr. Walker.” William wrote. “I had served him one year and it was the longest year I ever lived.”

One of William’s most emotionally taxing jobs was when he worked once again on the steamboat Enterprize. Being hired by a slave trader, called Mr. Walker, William was assigned to a term of one year as a soul-driver: a slave forced to enchain and sell other slaves, oftentimes tearing apart husband and wife or children from their mothers. “When I learned the fact of my having been hired to a ‘soul-driver,’ no one can tell my emotions,” William explained.

He tried his best to provide comfort to the other slaves, but it was almost an impossible task. Slaves were placed in a slave pen and were chained together. This space was “impossible to keep,” William recalled. His jobs were numerous and odd, such as plucking gray whiskers from the chins of old men or dying the slaves’ hair black with polish to make them appear years younger.

William was forced to make the captive slaves sing, dance, jump, and play cards in the sale yard while tears slid down their faces. They were made to act “lively” while being inspected by White slave owners who frequently took them away from everyone they loved. This was its own form of imprisonment for William and made him “heart-sick at seeing fellow creatures bought and sold.”

While enslaved as a soul-driver, William was forced to partake in the slave trade firsthand. He experienced suicides, beatings, families being torn apart, and unsanitary conditions. One of his worst experiences as a souldriver—as commemorated in one of his poems—was when William’s master, Mr. Walker, took a crying infant from his slave mother, “gifting” it to a White woman housed nearby to get rid of its “damned noise.”

Eventually, William’s year as a soul-driver ended and he was able to return home. “After selling out this cargo of human flesh, we returned to St. Louis, and my time was up with Mr. Walker.” William wrote. “I had served him one year and it was the longest year I ever lived.”

Returning from his year-long commitment, William was hopeful that he might be able to purchase his own freedom. His master greeted him when he arrived but would not look him in the eyes. William knew immediately that something was wrong. Dr. Young explained that he had sold William’s mother and siblings while William was aboard the steamboat Enterprize. He was now hard pressed for more money and would need to sell William as well.

Dr. Young made it known that he would not be selling him to a slave trader but that he would give William one week to “go to the city and find you a good master.” William was furious and responded, “I cannot find a good master in the whole city of St. Louis. … There are no good masters in the state.” When William begged to buy his own freedom after his many years of devoted service, his master quickly denied him. William left the plantation swiftly with a new plan—not to find another master but to escape from the chains of slavery once and for all.

William’s first task was to find his mother. He found her at her new master’s house in the city, and they escaped to the edge of the Missouri River. He had scouted out a skiff, a small boat, a few nights before, and they both boarded it before anyone realized they had gone missing.

Reaching the Illinois shore, William and his mother ditched their vessel, walking on foot along the main road through Alton, Illinois. The two remained in the woods during the day and traveled during the night, following the North Star through a thick sheen of midnight cloud cover.

Several days later, in the early morning, the two runaway slaves walked down a back road. Suddenly, three men on horseback approached them at a rapid pace and ordered them to stop. William asked their reason for halting their journey, and the man in charge fished a paper out of his pocket: a warrant for their arrest in return for a reward of $200. William’s body went stiff and cold, and his mother began to cry hysterically. Tragically, his second attempt at freedom had failed.

When William was returned to John Young in St. Louis a few days later, he found that his master was ill. William said, “Nothing brought more joy to my heart than that intelligence.” When Dr. Young was well enough to ride again, he made his way into the city and sold William to Samuel Willi, a middle-class tailor with only a few servants. Samuel decided to hire William out to a steamboat and collect the money from his labor.

William had a few days before he was to board his new assignment, the steamboat Otto, and asked for leave to visit his mother. It was granted, and he rushed to f ind her. William located and boarded the boat that his mother was being held on, which was setting sail toward a New Orleans cotton plantation. When she spotted her son, she grabbed him and pulled him close, begging him to leave her and to run to freedom.

“Do not, I pray you, weep for me,” she pleaded. “I cannot last long upon a cotton plantation. I feel that my heavenly master will soon call me home, and then I shall be out of the hands of the slave-holders!” Moments later, he was forced off the boat by her master as she yelled, “God be with you!” It was the last time that William would see his mother.

On the Otto, William described his master J. B. Hill as a “drunked, profligate, hard-hearted creature not knowing how to treat himself, or any other person.” His time there was short and unpleasant, as he ran into many old friends who were worn out, depressed, and losing hope.

Samuel, needing money and being more than happy to make a quick profit, sold William to Captain Enoch Price—a “steamboat owner and commission merchant.” Mrs. Price, the wife of Enoch, was proud of her servants, buying the best clothes for them to wear and the best carriages for them to drive. Mrs. Price told William upon his arrival of her plans to have him drive her carriage and marry another one of their servants—an 18- to 20-year-old slave named Maria. William had no interest in marriage, as he was planning to escape, and discreetly attempted to prove his disinterest without raising suspicion. Mrs. Price noticed his disinterest but continued her matchmaking efforts. She soon became convinced that William was in love with a neighboring servant girl named Eliza. Mrs. Price went so far as to purchase Eliza in hopes that William would marry and “settle.”

William’s new plan formed out of this purchase. He decided that he would convince both Mrs. Price and Eliza that he was in love with her. He hoped that this “love” would persuade everyone to believe that he had no intentions of escaping. All was going well, and the Prices decided to take a holiday to New Orleans and Cincinnati on their personal boat The Chester. They took William along with them to be a steward but hesitated keeping him on board as they approached the free state of Ohio.

One day, Captain Enoch pulled William aside to have a conversation. “Have you ever been in a free state?” He casually inquired. “I have been in Ohio, but I never liked a free state,” William replied, not falling for the trick. The conversation continued, William confidently proclaiming that with Eliza on the boat, “Nothing but death should part us! It is the same as if we were married.” With this, the decision was made, and the boat carried him farther down the river toward Ohio.

The morning of William’s escape, he took only a wellworn suit and a few provisions with him. The boat had just landed, so he tried his best to blend in with the other off-boarding passengers on the dock, randomly grabbing a trunk and walking swiftly to the wharf. Soon, to his own disbelief, William came to the woods where he remained until deep into the night. So far, no one had detected his escape. Since his past experiences of being recaptured burned in his brain, William was determined not to trust any man, Black nor White, on his journey to freedom.

With a single tinder box and a thin overcoat, William did his best to stay warm. Regardless, his limbs became like ice, and his provisions quickly ran out. He hobbled to a barn but found only a few heads of corn. He took them, roasted them, and lay quietly in the Ohio woodlands as night continued on. While lying in the brush and staring at the clear night sky, William’s fever raged and his frozen limbs ached. However, death, William recounted, was not of as much concern as having to return to slavery. Night turned to morning, and he cautiously continued on as the sun rose, knowing that he must increase the distance between himself and the Prices or be caught once again. With his debilitating fever, William considered taking a major risk: flagging down a traveler and asking for help.

Wells Brown, a White man and secret abolitionist, came walking along the road that same morning, leading a horse. As soon as William spotted him and despite his resolution to trust no one, he took a chance and came out of hiding. “I thought to myself, ‘You are the man that I have been looking for!’ Nor was I mistaken. He was the very man!” William said.

After approaching William, Wells inquired if he was a slave. William stared at him, scared and unable to answer, and eventually asked “if he knew of anyone who would help me, as I was sick.” Wells asked again if William was a slave, and upon his confession, he told William that he had gotten himself into a very proslavery neighborhood and asked if he would wait in the woods until he returned. Out of options due to frostbite and fever and desperate not to go back to Missouri, William placed his life into the stranger’s hands.

Over an hour of time passed, and while skeptical of any help arriving, William stayed put in his hiding place. Eventually, Wells returned with a covered wagon for William to hide in while being taken to safety. Wells took William to his home, but William refused to enter until the wife of his host came out and greeted him. “I thought I saw something in the old lady’s cap that told me I was not only safe, but welcome, in her house,” wrote William. His instincts were right, and the only fault that William found with the Browns during his time in their home “was their being too kind.”

William hesitantly walked into the Brown home and slowly sat at their dining table. “I had never had a White man to treat me as an equal, and the idea of a White lady waiting on me at the table was still worse!” William said. “Though the table was loaded with the good things of this life, I could not eat. I thought if I could only be allowed the privilege of sitting in the kitchen, I should be more than satisfied!” Due to his appetite being gone, Mrs. Brown made William a cup of “number six,”—a warm drink with rum—which was “so strong and hot that I called it number seven!” said William.

After enduring excruciating circumstances under the hand of John Colburn, William was transferred to the St. Louis Times under the supervision of Elijah P. Lovejoy. Elijah was the editor and publisher of the St. Louis Times, and William spoke highly of him in many regards. “Mr. Lovejoy was a very good man, and decidedly the best master that I had ever had. I am chiefly indebted to him,” William wrote, recalling that much of his early learning with reading and writing was attained while working there.

African American studies professor Patrick F. Ryan at Hilbert College in Buffalo, New York, adds, “This was [William’s] first time seeing antislavery papers, and Lovejoy did help him learn. Elijah went on to be a noted abolitionist.” At only 35 years old, Elijah’s print shop was burned to the ground, and he was murdered by a proslavery mob.

While working at the Times, William ran the press and served the staff. He also ran errands to the Missouri Republican, run by Edward Charles. One of these trips almost ended his life.

Several of the sons of local slave owners attacked William one day on his journey to the Missouri Republican office. They pelted him with their fists, snow, stones, and sticks. He did his best to fight back and defend his life, barely making it back to Elijah’s office. One of the boys’ fathers, called Mr. McKinney, claimed William had “hurt his boy.” The father found William, took him by the collar, and struck him over the head with a cane over and over “in such a manner that my clothes were completely saturated with blood,” William recalled. After seeing his condition, Elijah sent William back to his owner John Young’s plantation to recuperate. It was five weeks before William could walk again. To his dismay, William was informed that he had lost his position with the St. Louis Times and had been transferred.

Sweet Freedom’s Plains

Throughout his stay, the Browns and William became fast friends. He said that they treated him “as kindly as if [he] had been one of their own children.” They helped to heal his frostbite and gave him bed rest until his high fever broke after twelve days’ time. Upon nursing, feeding, and fully clothing him with a new set of winter clothes, the Browns prepared to send William farther north to safety.

Before he left their home, Wells asked what his new friend’s full name was. When William replied that he had no given last name, Wells said that he must have another name, because with his escape from slavery, “he was now a man, and men always have two names.” Wells Brown then offered his own name to William, which he took gratefully. He left the Brown residence as a free man with a new identity: William Wells Brown.

A Self-Made Success

After achieving his freedom, William took work with a family in Cleveland, Ohio. He would give barley sugar sticks to the family’s two young children, John and David, in exchange for “ABC’s lessons” in the loft of their barn where he stayed. By the time he left the family, he knew the alphabet, the basics of reading and writing, arithmetic, and grammar. After leaving the family, William moved to Boston, Massachusetts, and married Elizabeth Spooner in 1834. William had three daughters with Elizabeth, one of which passed at birth.

Professor Patrick F. Ryan gives additional insight on how an advanced education became a possibility for William. He says that William’s wife, Elizabeth, helped William to understand advanced reading and writing. “You can also look at his time in Elijah P. Lovejoy’s print shop (late 1820s),” says Patrick. “You can point to these two figures as being instrumental in Brown’s education.”

Patrick adds, “It is so unbelievable. He was an enslaved person who wasn’t taught to read or write. He didn’t escape into freedom until his late teens, early 20s. He went from not being able to read or write, to being the first published African American to write a play, to write a novel, and to be a world-renowned author.”

William’s first novel was released in 1847, Narrative of William W. Brown, a Fugitive Slave. A letter was sent to William from his close friend Edmund Quincy Dedham on July 1, 1847, before his book was published. Edmund wrote, “I trust and believe that your narrative will have a wide circulation. I am sure it deserves it.” His friend was right, as William’s novel sold a surprising 18,000 copies in its first year in circulation. The question asked in the book’s foreword written by J. C. Hathaway, “Reader, are you an abolitionist?” was not well-received, but the high rate of sales on William’s book told a different story.

In addition to his first book, William wrote and published many others. “One notable work was The Escape. Narrative of William W. Brown, an American Slave And that was a play that he wrote detailing African Americans escaping from slavery,” says Patrick. This was the first play to be published by a Black writer in the United States. “Another, and probably what he’s most known for on an international stage, was Clotel.” According to Patrick, Clotel was “quite the jump for a had worked together to purchase Frederick Douglass’s person of color back then.” The book told the tale of Clotel and her sister—Thomas Jefferson’s two fictional daughters born from his slave Sally Hemmings. “It was one of the first times that an African American was given the ability to write, had it published, and was able to challenge the hypocrisy of the early American leaders,” says Patrick.

After releasing a few different books in the United States and becoming a best-selling author, William befriended Frederick Douglass. They worked together to coordinate the 54th Regiment of Massachusetts—a Black Civil War regiment—until William was invited to speak at the International Peace Conference in Britain. Around this time, the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 was passed, requiring that runaway slaves be returned to their owners, no matter if they resided in a free state.

William moved to England for five years to avoid his recapture and to speak at antislavery conventions. During this time, he also began studying medicine and became a physician. Before leaving England, two high-profile women—Anna Richardson and her sister-in-law Ellen Richardson—raised the funds to purchase William’s freedom from Enoch. These were the same two women that had worked together to purchase Frederick Douglass’s freedom just a few years before.

Later in his life, William single-handedly saved the lives of over 69 Black slaves through his work on the Underground Railroad. Because of his extensive work on steamboats, William knew how to maneuver within the steamboat system and provided passage for many from Buffalo, New York, across Lake Erie, and into Canada.

A Final Farewell

Today, at Cambridge Cemetery in Massachusetts, 66 acres of soft green grass carpet a vast landscape. Though he was laid to rest in Cambridge, William Wells Brown’s grave went unmarked for many years. Today, a headstone briefly marks his accomplishments and his lifespan.

At the end of his first published novel, William wrote an epigraph dedicated to his friend Wells Brown who saved his life many years before. His warm thanks to Wells proves the impact of kindness:

“Thirteen years ago, I came to your door, a weary fugitive from chains and stripes. I was a stranger, and you took me in. I was hungry, and you fed me. Naked was I, and you clothed me. Even a name by which to be known among men, slavery had denied me. You bestowed upon me your own. Base indeed should I be, if I ever forget what I owe to you, or do anything to disgrace that honored name! … In the multitude that you have succored, it is very possible that you may not remember me; but until I forget God and myself, I can never forget you. Your grateful friend,

William Wells Brown.”

This article was originally published in the January/February 2025 edition of Missouri Life magazine.