Bone-biting brisk winter mornings may make most Missouri animals burrow in but that’s the time when one special deer herd comes alive. Their arctic roots have primed these reindeer for blustery days, so by the time members of the Scull family get to the barn at sunrise to feed them a breakfast of pelleted grain, hay, and beet pulp, they’re already frolicking happily.

Jeremiah Scull and his wife, Kari, and their two daughters have been raising a small herd of reindeer since 2014 at their farm called Show-Me Reindeer LLC in Robertsville. Each winter, the Sculls trot the reindeer around the state as living Christmas traditions. Almost every day leading up to Christmas, the Sculls bring pairs of reindeer to participate in tree lighting ceremonies, promotional events, private parties, open houses, holiday festivals, and parades. They rotate the deer so that none of them spends too much time on the road, and they always bring two so they can keep each other company.

Even though appearing at so many events can get hectic at one of the busiest times of the year, Kari says her family looks forward to each December because they get to share the real spirit of Christmas.

At the events, the Sculls set up a magical Christmas scene. After researching 19th-century sleighs, the couple began refurbishing antique sleighs and harnesses with gold stencil and era-correct upholstery. They set up photo ops and bring shed antlers for people to feel, but they don’t allow folks to touch or pet the reindeer. The no-touch policy helps the reindeer stay calm and safe amid the bustle of tree lightings and Santa appearances.

Sometimes, the people who make it out to see the reindeer don’t believe what they see. “People just can’t believe reindeer are real, given the myths and the story about Rudolph,” Jeremiah says. “Seeing an actual reindeer up-close and in-person is a rare opportunity.”

One encounter with an admirer sticks out for Kari. “One of the most memorable people was a 95-year-old woman, who said she’d never seen a reindeer except in picture books,” she recalls. “She was really surprised and amazed at them.”

It’s hard to think of Christmas lore without visions of sugarplums and the prancing and pawing of hooves on the roof. But the importance of reindeer in the Christmas tradition is only a couple of hundred years old. Santa’s reindeer-powered sleigh was immortalized in the early 1800s with Clement Clarke Moore’s ’Twas The Night Before Christmas. Rudolph didn’t enter the picture until 1939.

But the mythos of reindeer goes far beyond Rudolph’s holiday-saving power of nasal illumination. According to Robert Sullivan’s Flight of the Reindeer, humans have enjoyed the idea of airborne reindeer for more than 5,000 years, with several ancient instances of floating reindeer painted on cave walls. In Norse mythology, Thor’s chariot was first pulled by goats that transformed into reindeer. One of the labors of Heracles, or Hercules to the Romans, involved capturing the Cerynian Hind, which was sacred to Artemis. Scholars have since identified the skin as probably from a reindeer.

At the Sculls’ Franklin County farm, the reindeer have yet to take flight. But even with their hooves on the ground, this merry little band helps keep the magic of Christmas alive in Missouri.

Maintaining a healthy, domesticated reindeer herd is similar to caring for other livestock, especially horses, Jeremiah says. “We had to find the proper balance for their diet and learn about how their needs change, but we have to buy select hay from northern Missouri because they don’t like the stems that typically are found in local hay,” he says. The family also had to find veterinarians who could take on the animals.

To exhibit the reindeer at holiday events, the Sculls are certified with the US Department of Agriculture. Their reindeer, the farm, and transportation plans are monitored and inspected by officials, per regulations associated with herd health conditions.

A Herd of Their Own

Reindeer round out a livestock population at the Scull family farm that includes pygmy goats, chickens, ducks, guineas, and turkeys. The reindeer spend nights in their own barn and days roaming a fi eld and lounging in the shade of large oak trees. There’s an 8-foot fence surrounding the reindeers’ pasture, but it’s mostly to keep other deer out, Jeremiah says. Contrary to their aerial reputation, reindeer don’t do much jumping.

The Sculls spend time with the reindeer every day. Their oldest daughter, 8-year-old Addie, often leads them on walks to nearby clover patches.

“Reindeer really need as much 24/7 monitoring as we can provide, to make sure their antlers don’t get caught on fencing, tree limbs, or each other,” Jeremiah says. Reindeer antlers grow in an upward span so they can use them to dig up plants buried in the snow. In the wild, the animals also often use them to ward off predators.

When reindeer antlers grow, they are soft and flexible, nourished by a vascular covering referred to as velvet, which is a mass of blood and marrow. “Antlers are very tender and vulnerable during velvet growth time, and a broken antler tip is a huge health threat to them at that point, because an opening can attract flies, which can lead to deadly infections,” he says.

With veins near the surface, the antlers feel warm to the touch. Nerves grow at the same rate as the antlers, so reindeer are extremely sensitive if their antlers are touched while they are in velvet, Kari says. To help the herd with the velvet-shedding process, the Sculls constructed homemade rubbing devices from huge street sweeper brushes. Sometimes, they assist the steers by hand with stripping off the velvet. Kari says they spend extra care monitoring the reindeer’s antlers, even applying Avon’s Skin So Soft product on them as a natural insect repellent.

Raising Reindeer

The Sculls got the idea to raise reindeer after taking Addie to visit a reindeer at a local farm supply store.

The family fondly remembers a pair of calves, Prancer and Sven, they bought three years ago. In the summer of 2015, Sven contracted ehrlichiosis, a tick-borne disease. His unexpected passing was hard on the Scull family. Later that year, the Sculls brought home the parents of the calves, father Blitzen and mother Dasher, in hopes of expanding the herd.

Each reindeer has its own personality and shares a special bond with family members. Blitzen is the proud king of the herd, Dasher is queen, and a gaggle of energetic younglings make up the rest of the group.

Blitzen is the only bull on the farm, and he usually stays behind at events. He and Dasher often snuggle together, and he looks out for her most of all. Their son, Snowflake, is the first reindeer born on the farm. He arrived on April 19, 2016, weighing a mere seven pounds. Addie and her 4-year-old sister, Audrie, named him fittingly, as he has the whitest winter coat of the herd. Snowflake often hangs around his dad and receives plenty of attention from his mother, but the Sculls say Snowflake is the practical joker of the family; he’s always looking for trouble. Kari says they like to tell him, “You have the beauty of your mother, but the orneriness of your father.”

Siblings Comet, Cupid, and Dancer joined the herd in the fall of 2016. Comet and Cupid are the best of friends, though they don’t agree on the pleasantness of walks. Comet loves his daily jaunts, but Cupid, the shyest of the bunch, took time to warm up to the idea.

Dancer, the only other female, is the smallest of the herd but has the most courage. She gives her brothers a run for their money when they play and run together, and she is always the first at the feed trough.

Dancer’s best friend was Prancer, the Sculls’ “love bug” after losing his brother, Sven. Prancer always greeted the Sculls at the farm-lot gate, ready to go on a walk or to be at a show. The family showered him with hugs and kisses, and he and Addie often went on walks together.

In October, Prancer became suddenly ill. Within a matter of hours, he was unable to move. As Jeremiah and Kari consulted veterinarians and prepared to take him to the University of Missouri animal hospital in Columbia, he faded faster. Finally, Jeremiah woke up Addie and told her that they were going to take Prancer to the vet and that she might want to say goodbye. The Sculls gathered around Prancer in the barn, holding him and petting him. As Addie began petting his head, Prancer took his last breath. “It was like he waited for her,” Jeremiah says.

Jeremiah says their daughters seem to have handled the loss better than the adults. When Jeremiah talked to Addie about it, Addie was calm. “It’s okay,” she told him, “I’ll just have to take his buddy Dancer on walks now.”

For Addie and other believers who meet members of the herd across Missouri, the Sculls deliver an invaluable gift. To the people who see the reindeer, the animals represent the joy of Santa, the warmth of the holidays, and more than a little magic.

Photos by Dennis Coello

See the reindeer at one of these events!

December 1: Jefferson City

Downtown Living Windows

6 PM to 9 PM

December 2: Belleville

Christkindlmarkt

1 PM to 4 PM

December 2: Winfield

Light Up Winfield

6:30 PM to 8:30 PM

December 3: Valley Park

Santa Claus is Coming to Town

2 PM to 4 PM

December 7: St. Charles

Lutheran Senior Services Breeze Park

10 AM to Noon

December 7: Richmond

City of Richmond

4 PM to 8 PM

December 8: Belleville

Christkindlmarkt

5 PM to 8 PM

December 9: Kirkwood

Museum of Transportation

Noon to 4 PM

December 9: Pacific

Christmas on the Plaza

6 PM to 8:30 PM

December 12: Granite City

Illinois, Six Mile Regional Library

5:30 PM to 7:30 PM

December 15: St. Clair

Farmers & Merchants Bank

1 PM to 3 PM

December 15: Centralia

Lighted Tractor Parade

6:30 PM to 8:30 PM

December 16: Edmundson

Visit with Santa

11 AM to 1 PM

December 16: St. Charles

Christmas Traditions

3 PM to 5 PM

December 17: Belleville

Christkindlmarkt

10 AM to 1 PM

December 17: St. Charles

Christmas Traditions

3 PM to 5 PM

December 18: Town & Country

Visit with Santa at Whole Foods

Noon to 2 PM

December 19: Lebanon, Illinois

Cedar Ridge Health Center

2 PM to 4 PM

December 21: Eureka

Farmers & Merchants Bank

1 PM to 3 PM

December 22: Belleville

Christkindlmarkt

2 PM to 5 PM

December 22: High Ridge

Farmers & Merchants Bank

9 AM to 11 AM

December 24: Alton, Illinois

Visit with Santa at Duke Bakery

10 AM to Noon

Related Posts

James Sidney Rollins is Born: April 19, 1812

James S. Rollins was born on this day. Many recognize Rollins as the Father of the University of Missouri.

Game On!

They say the house always wins, but community takes the jackpot at Vintage Vegas Casino Night. Sponsored by Vision Carthage, the event features food, drink, and plenty of casino-style fun. Proceeds benefit local charitable initiatives.

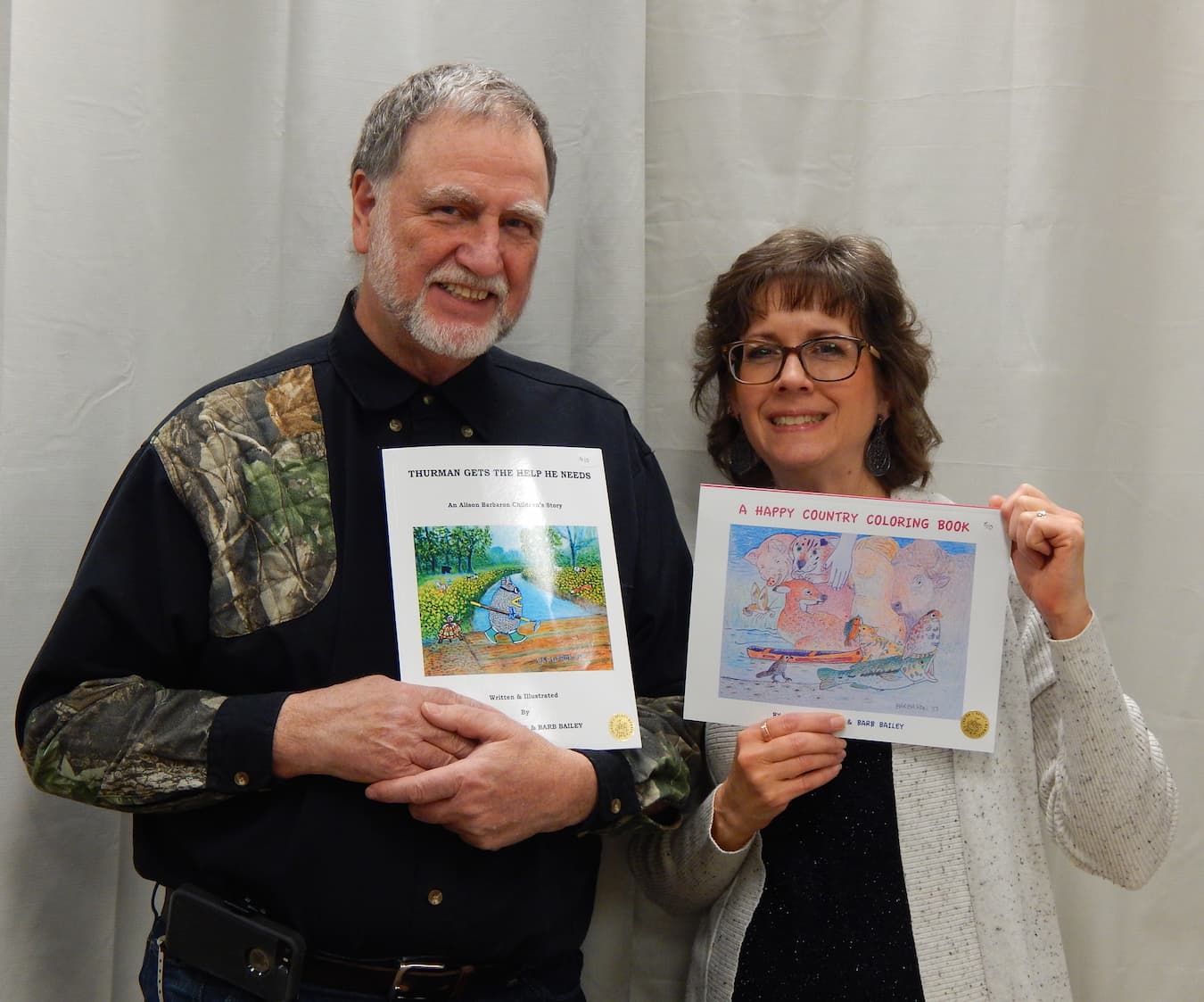

Better Together

These two Cape Girardeau painters write and illustrate children's books in an unconventionally collaborative way. Their method is a fast-paced give-and-take that requires absolute trust, open minds, and a willingness to pick up and pivot.

MO News is Good News – April 19, 2024

Big things are always happening in Missouri. In this week’s headline roundup, we’ve got big bugs, big fish, big money, and your big chance to land on national TV.