The Civil War was less than 5 months old in early September of 1861 when three regiments of free-state volunteers crossed the border separating their home state of Kansas from western Missouri. Described by one chronicler as a “motley force of patriots, murderers, and plunderers,” they were well-armed; in addition to their rifles and sidearms, they hauled two field pieces. As evidence of thoughtful preplanning, many drove wagons in which to haul the plunder they planned to snatch from the unfortunate towns on their itinerary.

At the head of the 1,400-man brigade rode their organizer and commander, Senator James Henry Lane. Known as the “Grim Chieftain,” Lane had informed his men that their mission and sole purpose was to “play hell with Missouri.” It was a command they would more than willingly obey, sharing as they did their leader’s views of their neighbors.

“Missourians,” Lane had said, “are wolves, snakes, devils, and damn their souls, I want to see them cast into a burning hell! We believe in a war of extermination. … I want to see every foot of ground in Jackson, Cass, and Bates Counties burned over, everything laid waste.”

Lane’s “jayhawkers,” as antislavery guerrillas from Kansas were called, proceeded to visit their vicious brand of havoc on the towns of Butler, Harrisonville, West Point, and Papinville. After a brief skirmish with rebels, they burned the village of Morristown, and shot nearly a dozen townspeople for resisting. Nor did they spare the farms along their route. At both union- and rebel-owned farms, the raiders seized, killed, or drove off livestock, “confiscated” furniture and other household goods, randomly abused the citizenry, and encouraged slaves to run off or join Lane’s band. The men of Lane’s Brigade performed their most thorough work, however, on September 22, when they arrived at the town of Osceola.

The Bloodletting Begins

The violence that characterized the state of affairs along the Kansas and Missouri border predated the Civil War by several years. It began with the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854. Aside from creating the territories of Kansas and Nebraska, the ill-considered and highly controversial legislation also allowed their citizens to decide by popular vote whether to enter the Union as a free or slave state.

The new law, which was popular with virtually no one, undid all previous legislation that had defined and limited the expansion of slavery, and it paved the way for what would become, in another seven years, the nation’s most cataclysmic conflict.

Antislavery “free-soil” settlers from New England and other northern states and proslavery immigrants, largely from Missouri, descended upon Kansas in droves, each faction set on determining the territory’s status. “Bleeding Kansas,” as it came to be known, reflected the divisions that were riving the country. A major new antislavery political faction, the Republican Party, arose as a result of widespread political upheaval, and one of its luminaries was an Illinois lawyer and politician named Abraham Lincoln.

Kansas became a breeding ground for fanatics on both sides. One of the most notorious was John Brown, the northern abolitionist whose last words were a prophetic indication of what was soon to follow: “I, John Brown, am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land can never be purged away but with blood.”

There were many who espoused his sentiments; one of these was James Henry Lane.

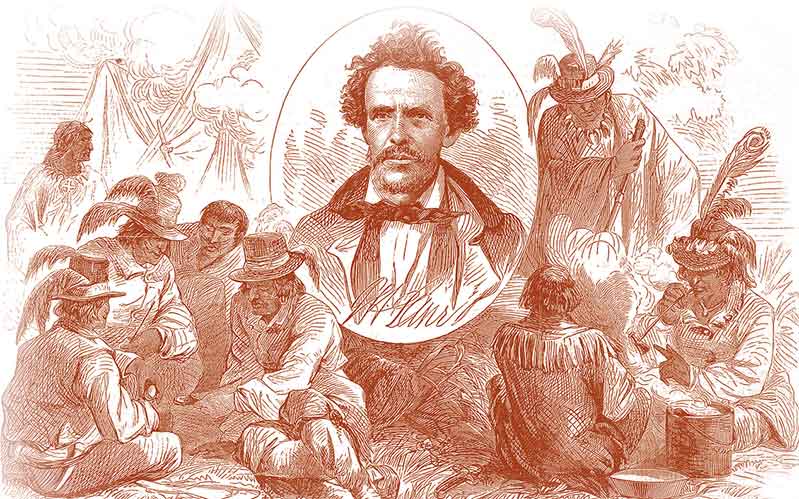

Rise of a Fanatic

Raised in Indiana, Lane had fought in the Mexican War and was a declared proslavery Democrat. At one point, he had stated, “I would as soon buy a Negro as a mule.” However, Lane knew an opportunity when he saw it. A dedicated self-promoter, he moved to Kansas Territory in 1855, where—after evaluating his circumstances with what historian Richard Brownlee calls “cynical objectivity”—he saw a chance for advancement in espousing the free-soil cause as a proponent of the new Republican Party.

By all reports, Lane was severely lacking in moral character. Chronicler Paul Petersen calls him “an unscrupulous opportunist in both his personal relations and political associations … violent, paranoid, and highly unbalanced.” Lane, writes Brownlee, “represented the worst aspects of fanaticism.”

Physically, Lane was far from prepossessing. He was thin bordering on gaunt—a

reporter referred to him as “eely-shaped”—and exceedingly homely. As his photographs show, he exhibited a dour aspect. His hair stood wildly in all directions, and Brownlee describes him as an “evil-looking creature with the sad, dim-eyed, bad-toothed face of a harlot.”

Apparently, however, he was a natural leader with a gift for captivating an audience. Hearing Lane speak, a contemporary called his mannerisms “voluble and incessant, without logic, learning, rhetoric, or grace,” spoken in “a series of transitions from the broken scream of a maniac

to the hoarse, rasping guttural of a Dutch butcher in the last gasp of inebriation.” His vocabulary “was a pudding of slang, profanity, and solecism,” and “the electric shock of his extraordinary eloquence thrilled.”

In 1856, Lane gave a fundraising speech in Chicago on behalf of the free-soilers of Kansas. According to local newspaper accounts, the talk raised an astounding $15,000—more than $400,000 in today’s currency—and when he finished, gamblers threw their pistols on the stage and begged Lane to take them west. Businessmen threw their purses, newsboys tossed pennies, women wept, and people milled around the platform in a high state of agitation.

So persuasive was Lane that he became the unchallenged leader of Kansas’s free-soilers, even after he was tried but acquitted for shooting and killing his neighbor over a land dispute. When Kansas became a state in early 1861, he convinced its citizens to send him to Washington as their senator.

Upon arriving in the nation’s capital, the savvy Lane set about winning over newly elected President Abraham Lincoln. He formed the 60-man “Frontier Guard,” a volunteer outfit composed mainly of Kansans, and installed them in the East Room of the White House, ostensibly to protect the president. Lincoln’s secretaries, John Nicolay and John Hay, were less than sanguine over their presence, complaining that the rough-hewn company staged “rudimentary squad drill under the light of the gorgeous gas chandeliers.” But Lincoln, impressed with Lane’s initiative, became an immediate ally of the new senator, despite the negative feedback Lincoln regularly received from numerous sources.

Shortly thereafter, Edwin M. Stanton, Lincoln’s secretary of war, gave Lane authorization to raise troops on behalf of the Union. Upon returning home to Lawrence, he set about doing just that, assembling “Lane’s Brigade,” consisting of two volunteer regiments of cavalry and one of infantry. Lincoln put forth Lane’s name as a brigadier general of volunteers, uniquely making him both a sitting senator and a general officer.

Kansas Governor Charles Robinson, who had known and disliked Lane for some time, viewed his activities with trepidation, warning that “Lane’s brigade will get up a war by going over the line, committing depredations, and then returning to our state.” Robinson could not have been more prescient. Lane had a plan, and by late summer, he was ready to put his plan into action.

Crossing the Line

Far from entering Missouri to do battle with Confederate units, Lane planned to follow in the wake of rebel general and former Missouri Governor Sterling Price’s

12,000-man Missouri State Guard. He intended to punish every community that had given aid and comfort to Price and his men. It was by far the safer strategy.

For his part, Price was resolved to drive all Union men from the state and secure Missouri for the Confederacy. Thus far, he had been highly effective, having scored an impressive victory at Wilson’s Creek the previous month. Taking place only two weeks after the Union rout at First Bull Run, it was the second major battle of the war, and the first west of the Mississippi.

Inevitably, Lane’s Brigade would run the risk of encountering the enemy, and it happened almost at once. Shortly after crossing the border, they briefly engaged a contingent of Price’s Confederates at Dry Wood Creek and came out losers, taking some five casualties. Lane immediately requested reinforcements from the War Department, citing the need to keep Kansas from “disgrace and destruction.” Washington refused, informing Lane that federal troops were more sorely needed elsewhere and assuring him that southern Kansas was not in immediate danger.

Resolved in his purpose and furious over his defeat, Lane continued farther eastward, looting and pillaging as he went. At around 2 o’clock on the morning of September 22, 1861, his band of jayhawkers descended on Osceola.

The Sack of Osceola

From its founding at the junction of the Osage and Sac Rivers in the mid-1830s, Osceola—named for the famed Seminole warrior chief—had grown into a comfortable town of some 3,000 citizens. It had become the St. Clair County seat in early 1841 and served as a commercial hub, receiving goods from New Orleans off the Osage River steamboats and transporting them overland to the south and west.

At this time, however, practically all of Osceola’s men of fighting age had left to join Price’s State Guard and were currently engaged in fighting Yankees at Lexington. With the town occupied mainly by old men, women, and children, Lane could not have timed things better.

Word of Lane’s coming had reached the townsfolk, and some 20 militiamen of the Missouri State Guard met the brigade with rifle fire. Severely outgunned and outmanned, the small company soon withdrew, leaving the town unprotected.

Lane had heard that Osceola was holding supplies and money earmarked for the rebels. His first stop was the bank, where $100,000 was supposedly deposited. The bank staff, however, had removed and buried the money prior to Lane’s arrival, and he found the vault empty. Furious, he ordered the town destroyed.

The brigade’s two cannons leveled the courthouse as Lane’s men put torches to Osceola’s other buildings. The looting that followed virtually emptied the town. According to local historian Richard Sunderwirth, Lane’s Brigade made off with “tons of lead, 3,000 sacks of flour, 500 pounds of sugar and molasses, 50 sacks of coffee, 350 horses, 400 cattle, powder kegs, silk dresses, shoes, sugar, bacon slabs, furniture, barrels of brandy, and other items.”

Sunderwirth adds that Lane liberated 200 slaves; some ran away while others accompanied Lane’s men when they left Osceola. At this early stage in the war, the emancipation of slaves was expressly forbidden by law and by Lincoln himself. Lane was well aware of this, but said, “[C]onfiscation of slaves … should follow treason as the thunder peal follows the lightning flash.”

The Kansans also burned the town’s store of liquor, after consuming a share of the whiskey. Reportedly, the fire sent a “stream of flames” all the way down to the Osage River.

According to some historians, Lane had a dozen or so residents rounded up and shot. No documentation of such an event exists, however, and it is probable that the story became confused with the earlier events in Morristown. It is certain, however, that innocent civilians died during the raid. Today, a monument stands in the town cemetery, reading: “In memory of citizens of Osceola murdered by Kansas jayhawkers and the Union Army.”

Writes Richard Brownlee: “At Osceola, the Kansas Brigade established its outlaw reputation on the border.” When Lane’s men rode out of Osceola, he says, they had pilfered or destroyed an estimated $1 million in property. Some 300 of Lane’s men were so drunk they had to be carried in wagons along with their plunder. The town lay in smoldering ruins, all but three of its buildings burned to ashes. Lane lost no men in the raid, but the estimates of civilian deaths range from 15 to 20.

Aftermath

Lane’s Missouri campaign outraged unionists and secessionists alike. Kansas Governor Robinson fumed, as did Fort Leavenworth’s federal commander, Major W. E. Prince. When he received word of the raid on Osceola, Union General Henry Halleck, commander of the Department of Missouri, was furious.

“The course pursued by those under Lane,” Halleck thundered, “has turned against us many thousands who were formerly Union men. A few more such raids will make this State unanimous against us.”

Halleck’s dire predictions proved at least partly accurate. While Missouri sent 109,000 Missourians to fight for the Union, another 30,000 wore Confederate gray.

Lane claimed that his artillery had inadvertently set the fires that destroyed Osceola. However, Joseph Trego, one of Lane’s men, later averred that the brigade “loaded the wagons with valuebles [sic] from the numerous well supplied stores, and then set fire to the infernal town.”

For his part, President Lincoln did not condemn Lane, merely writing to General George B. McClellan, “I am sorry General Halleck is so unfavorably impressed with General Lane.” Lincoln referred to Lane in a letter to another of his generals, writing the man “who does something at the head of one Regiment will eclipse him who does nothing at the head of a hundred.”

Several of the slaves whom Lane had liberated in the course of his incursion later joined the First Kansas Colored Volunteers, a regiment that Lane himself had created. Writes historian Jeremy Neely: “In October 1862, [it] became the first African American regiment to see active combat during the Civil War.”

Two years after the sack of Osceola, rebel guerrilla leader William Clarke Quantrill staged a punitive raid on Lane’s hometown of Lawrence, Kansas. It was arguably the most brutal guerrilla raid of the entire war. As the avengers descended on the city, their war cry echoed: “Remember Osceola!” Quantrill’s men carried a death list, at the top of which was the name of James H. Lane. Although an estimated 150 citizens were murdered and the town devastated, Lane reputedly escaped in his nightshirt and hid in a cornfield.

After the war ended, Jim Lane grew increasingly despondent. His political star was in descent, and he had been accused of fiscal improprieties. In July 1866, he stepped out of a carriage in which he had been riding with his brother-in-law, and after bidding his companion goodbye, put a pistol in his mouth and pulled the trigger.

The extent to which Jim Lane actually believed his own antislavery rhetoric will likely never be known. Lane was a self-serving opportunist who used the passions of his supporters to fuel his agenda of destruction, and the towns of western Missouri paid the price. The Civil War cost the United States some three-

quarters of a million lives, and a loss in property that is yet impossible to calculate. Jim Lane and others of his ilk, on both sides of the war, made their own dedicated contribution to the death and destruction.

As for Osceola, only a handful of its citizens remained to rebuild the port town. They were only partially successful; recent census estimates peg the current population at slightly less than 900 residents. Lane’s raid, according to a May 12, 2015, article in the Topeka Capital-Journal, left “economic and emotional wounds from which the town is yet to recover.”

Related Posts

July 5, 1861

The Battle of Carthage was fought and the Confederates had their first victory.

March 13, 1861

Nathaniel Lyon took command of the St. Louis Arsenal on this day.

November 6, 1861

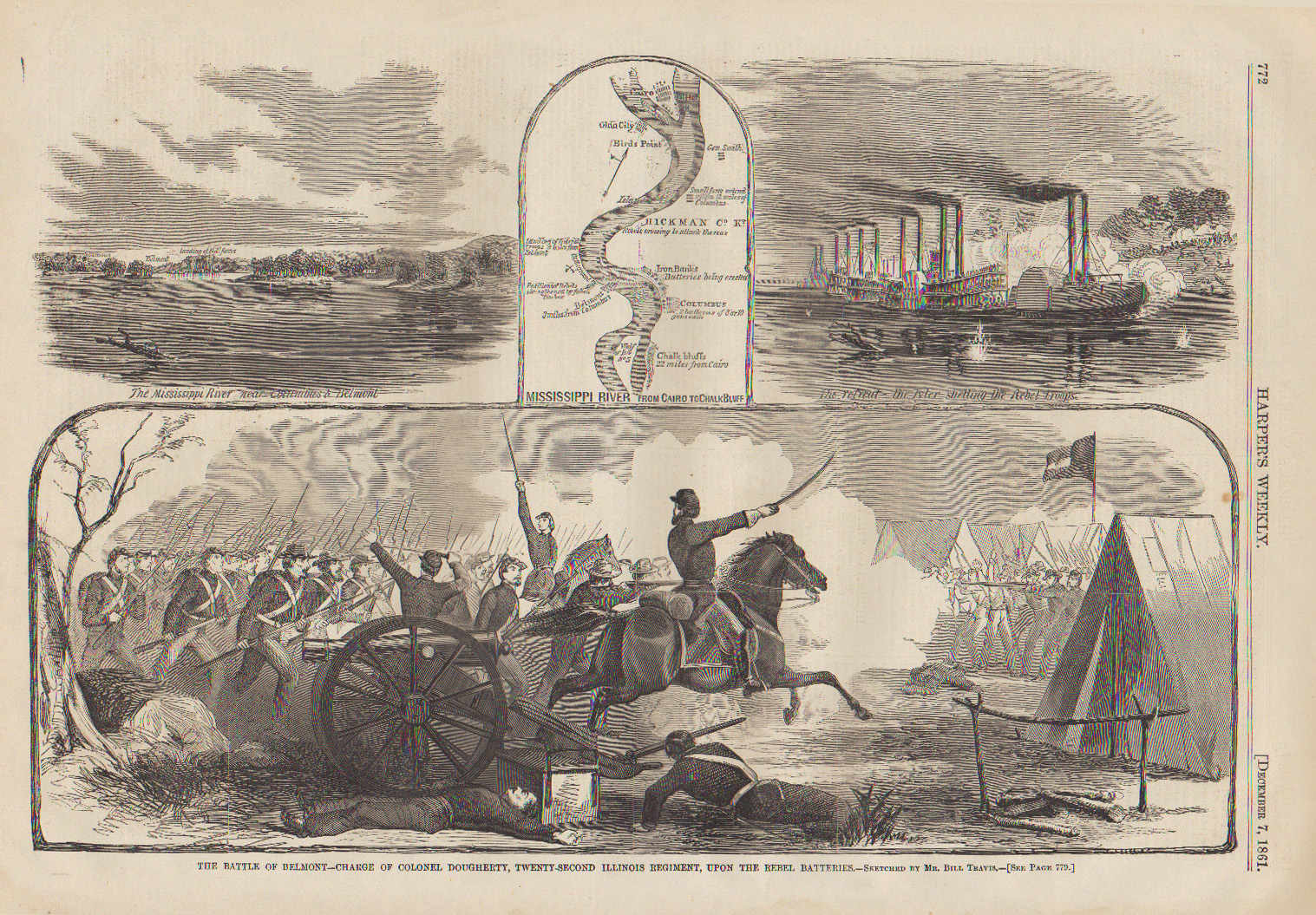

U.S. Grant sailed 3000 troops down the Mississippi to defeat confederate forces at the Battle of Belmont, Missouri.