The History of Missouri’s Flag

This article originally appeared in our June 2019 edition.

After entering the Union in 1821, Missouri went nearly an entire century without a state flag. The Missouri state flag was finally designed by Ray County native Marie Watkins Oliver. Known as the “Betsy Ross of Missouri,” Marie was chosen by her fellow Daughters of the American Revolution members in 1908 to chair a committee for the research and long-overdue creation of a state banner.

She completed the flag and took it to the state Capitol in Jefferson City for viewing by the legislature that year, but the bills to make it the official flag were voted down twice, in 1909 and in 1911. The original flag she made burned during the fire that destroyed the Capitol building in 1911, so Marie and another woman re-created the flag. Finally, the flag gained acceptance in 1913. In addition to its other heraldic symbols and devices, the seal in the center boasts three bears, the larger two representing “courage” and “strength.” Ironically, according to the Missouri Department of Conservation, “The bears on the Great Seal of the State of Missouri are grizzly bears, which never resided in the state.”

Only one species of bear is native to Missouri: the smaller American black bear. The grizzly, a subspecies of brown bear that ranges in the West, is larger with brown fur and a shoulder hump.

Although the huge omnivores were not native to Missouri, they nonetheless posed a vital threat to a handful of Missourians. In 1822, William H. Ashley of the newly formed Rocky Mountain Fur Company advertised in the St. Louis newspapers for “one hundred enterprising young men … to ascend the river Missouri to its source, there to be employed for one, two, or three years.” Among the party of trappers Ashley led out of St. Louis and up the Missouri River were Hugh Glass and Jedediah Smith, mountain men who would become legends on the frontier.

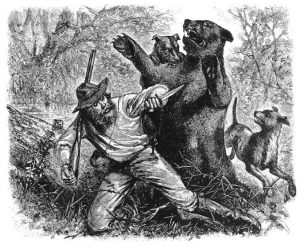

During one of his trapping forays, Jed Smith surprised a sow grizzly, which proceeded to bite down on his head, half tearing off his scalp and all but removing an ear before his fellow trappers dispatched the beast. Exhibiting the fortitude for which he had become known, Smith sat quietly, directing one of his no-doubt shaky comrades on the reattachment of his ear and hair.

Hugh Glass—“Old Hugh” to his friends—did not fare so well. There are many versions of Glass’s ordeal; this is the most commonly accepted. In late August of 1823, Glass also came upon a mother grizzly, this one with her cubs. By the time Old Hugh’s cries reached the ears of the rest of his party, the bear had mauled him so badly that death seemed imminent.

Glass lingered on, however, and since the party was in hostile Indian country, the brigade captain offered a cash payment to any two men who would stay with the horribly injured man and bury him when he expired. The others would make their way to Fort Henry at the mouth of the Yellowstone River.

Two men volunteered, John Fitzgerald and a teenaged Jim Bridger. For five days, Glass simply wouldn’t “go under,” and finally, the two men, terrified of an Indian attack and certain that the all-but-deceased trapper was not long for this world, took Old Hugh’s flint, knife, tomahawk, and rifle and abandoned him.

Incredibly, driven by thirst for both survival and revenge, Glass began to drag himself across the countryside. He had neither weapons nor the strength to use them. For sustenance, he ate anything from wild plants to insects and snakes. At one point, he came upon a buffalo calf felled by wolves. Glass waited for the predators to leave, then gorged on the meat the wolves had left, huddling beside the carcass until he regained some of his strength.

Weeks passed. Upon reaching the Missouri River, Glass received a hide boat from some friendly Sioux and made his way downriver. In mid-October, a wraithlike Hugh Glass pounded on the gates of Fort Kiowa, a Missouri River outpost some 250 miles from the site of the bear attack.

Apparently, this was only the first leg of his odyssey. After acquiring a rifle and other necessities, Glass set off on a hunt for Fitzgerald and Bridger. Several weeks later, he confronted the terrified teenager Bridger—Fitzgerald had left the region—and decided to forgive the young man, asking only that his rifle be returned. The 2015 film The Revenant tells this story on the silver screen, and Leonardo DiCaprio won an Oscar for his portrayal of Glass.

Foreign to Missouri though their species might be, the grizzlies on the state flag that represent “courage” and “strength” might very well have been named for such stalwart Missourians as Hugh Glass and Jedediah Smith.

Related Posts

108 Missouri Wineries

On December 11, 2012, state officials announced that there were now one hundred and eight commercial wineries operating in Missouri.

10 Books on Missouri’s Native American History

Looking for more reading on the Osage and Missouria tribes? Parts 2 and 3 of our special series are forthcoming in September and October, but in the mean time we highly recommend this selection of books that cover the subject.

Pickleball Is Taking Missouri By Storm

It took about a decade for pickleball to sweep Missouri. With more than 100 locations developed since 2010, Missouri might just have the fastest-growing pickleball community in the country.