Fire towers, once ubiquitous throughout the southern Missouri landscape, offer a bird’s-eye look at the countryside from their aeries perched high atop hills and ridges. These lookouts were the primary way to spot forest fires during much of the 1900s.

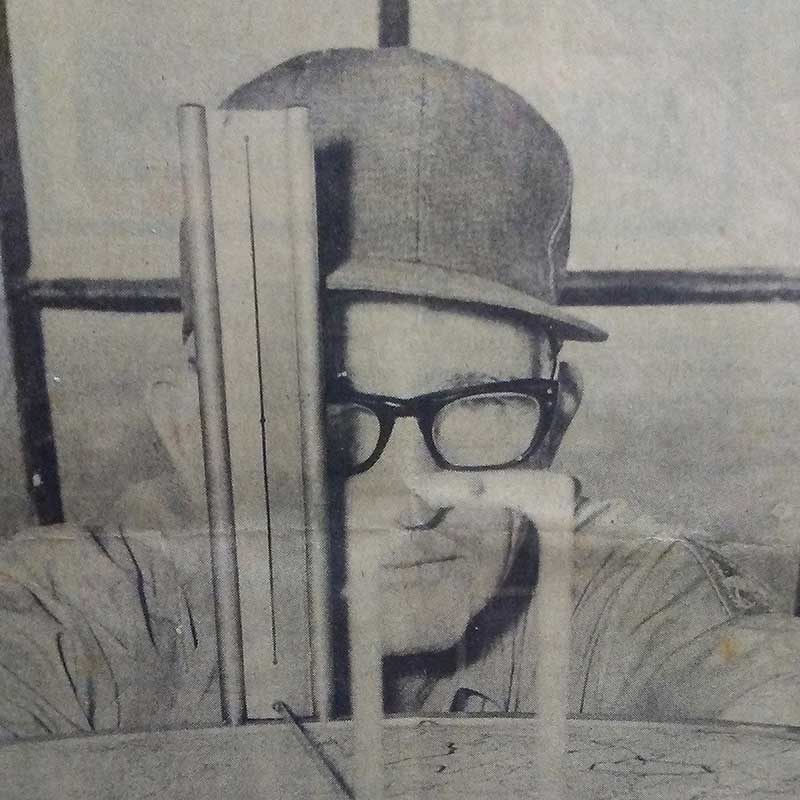

“Some towers are very impressive, when looking at them from the ground,” says tower aficionado Bob Frakes, “and for some, the cab view is quite extraordinary.” Bob, who lives in Illinois, has documented Missouri’s firetowers in a 324-page book, A Place Above the Trees: Remembering Missouri’s Lookout Towers, with more than 250 photographs, set to be published by Words Matter Publishing later this year.

Each forest fire watch tower has a cabin above the tree line where men and women have spent countless hours scanning for smoke or flames that might be miles away.

If smoke or fire appears in the 360-degree view, the watcher points the crosshairs of a tool called the Osbourne Fire Finder to record the azimuth, which is the angle between the projected object and a known reference point. This information helps estimate the distance of the smoke or fire and is dispatched to other towers and plotted on a map to determine the location of the fire. Then fire officials decide whether to investigate by ground, air, or both.

Once, there were thousands of fire towers across the country and nearly 260 in Missouri. Today, 65 are still standing in the Show-Me State. In the mid-1940s, fire watchers took to the air to monitor the landscape. Pilots worked full time at fire spotting into the 1960s. But as public knowledge and involvement in spotting forest fires became more prevalent, along with improvements in communications technology, the number of fires decreased, as did the need for air and tower surveillance.

Now these historical lookout structures are being closed, removed, or relocated to make room for cellular towers and other antennas. Fifteen of the towers still standing in Missouri are under the ownership of the US Forest Service and can no longer be climbed; another 50 are on Missouri Department of Conservation land.

Go even higher at our highest spot. The 72-foot Taum Sauk lookout, located at the highest point in the state, is on the National Historic Lookout Register. Built in 1949, it is the only tower in the state with a catwalk still in use.

TWO MEN AND A MAP

Bob Frakes has nurtured a lifelong interest in fire towers since boyhood when he visited his grandparents’ farm in Patterson, near Piedmont and Sam A. Baker State Park. He climbed Mudlick tower many times as a kid and often paddled his canoe along the Current River, where he could see and often climbed the Shannondale tower.

Now retired from a career as a high school social studies teacher, Bob enjoys traveling around the state to explore these pieces of history. Czar tower, about 40 minutes from Potosi, is one of his favorites because the pine trees perfectly frame the view of the tower, which is now closed.

“By definition, they are always at a high location, which means they are in some type of pretty setting on top of a hill or mountain,” he says.

Bob’s interest in fire towers caught the attention of St. Louisan Chris Polka, who also shares an interest in fire towers. Working with Bob, Chris created a map of all known fire towers in Missouri, both past and present. The Forest Fire Lookout Association uses the map as a resource on its website. (Visit FireLookout.org then click on Lookouts and Missouri.)

FIRE ESCAPE

Firefighting is fraught with excitement and danger. Jack Skinner can attest to that with recollections of stories from his late father’s life as a fire ranger and tower denizen. Glenn Skinner was superintendent of the Knob Lick fire tower from 1964 until his retirement in 1977.

Glenn helped build the Perry tower near Perryville in 1963. A year later, he transferred to Knob Lick, south of his home in Farmington, and stayed until he retired.

Although most workdays for rangers ran about 8 hours, sometimes rangers worked 16-hour days during peak fire seasons. If a major fire was burning, they might work around the clock.

One time, Jack recalls, Glenn was alone and surrounded by fire in the Higdon community. Unable to get out of the forest on fire, he waded into Castor River and spent the night on a rock in the middle of the river until daylight, when he could see a way out through the burned-out area.

For most people, bad weather might mean rain, snow, and ice, but those were good days for fire spotters because it meant no fire danger. At the height of fire season, as many as six to seven fires were possible each day.

When a ranger got a call about a fire, he might stop in the Knob Lick community to hire people to help fight the blaze. Glenn told his son that rangers suspected some locals were setting fires and then going back to town to wait to be hired to help.

Rangers fought minor fires with metal broom-rakes and water backpacks to spray the blaze, but if fires grew out of control, they requested backup—a bulldozer—from the main office in Perryville.

Jack enjoyed climbing the tower after his father became ranger at Knob Lick and reveled in the incredible view. He and his father relished watching the forest wildlife from on high, but Glenn occasionally had to climb down the tower and ask parking teenagers to leave.

In 2004, the Department of Conservation dedicated the Knob Lick tower in Glenn’s honor and attached a plaque to the side of the tower. Glenn had worked there longer than anyone.

A DAY IN THE LIFE

Lawrence Buchheit of Old Appleton was the only operator at the Perry tower. He retired in 2001 after working nearly 20 years at the structure.

A normal day for Lawrence began around 7:45 am with cleanup around the site. If the burn index was low or if it was raining, he didn’t spend as much time in the tower. But during springtime or whenever fire danger increased, Lawrence manned the tower for long hours. During times of high burn index, he stayed in the tower sometimes as late as 9 pm.

A typical day in the tower might include seeing nothing to as many as “20 smokes a day,” he says. “You learn how to tell a difference between a control burn and a wildfire.”

Weather kept things interesting. “If there was lightning in the area, you got out of the tower quickly,” Lawrence says. He remembers his first windy day in the tower, a structure meant to sway three to four inches. “But when you’re 100 feet off the ground, you know where your heartbeat is,” he says. “There are probably still some fingerprints on that steel where I held onto the handrail when I came back down.”

FINDING THE FIRE

On days with high wind, Steve Orchard says the constant popping sound from movement of the sheet metal cab makes a distracting sound, while the wind whistles through or around the cab, depending on whether the windows are open or closed.

Steve has manned fire towers for two decades at Hartshorn, Hunter, and Stegall. He has seen and documented thousands of fires. After a few years’ experience, he says, tower operators generally can pinpoint a fire within a 15-mile radius of the tower and within one square mile.

Fire spotters hone this skill with communications from fire suppression staff on the ground and the dispatcher, who checks reports radioed in from two or more adjacent towers.

Mounted on the wall of the dispatch office is a district map. A small circle indicates each tower location on this map. The circumference of the circle is marked with azimuth marks between zero and 360 degrees, viewed as if looking from the tower out to the horizon. At the precise location of the tower, a retractable string pulls out of the map and is placed across the map on the azimuth or “shot” the tower operator calls in. As other towers call in their shots on the same fire sighting, the dispatcher pulls strings and places them across the map. The intersection of the strings marks the fire location.

These same azimuth marks are also on each tower’s fire finder ring inside the tower and are used to determine the direction of the fire sighting, or “shot.”

“The best fire location comes from a three-way string cross on the map board after three nearby towers call their shot into dispatch,” Steve says. “Two shot crosses work well, and location from one tower only gives the fire direction unless the towerman has a view of the fire in good proximity to local landmarks.”

Radio communication further refines the fire location.

FROM THE AIR

Windy days were the only days David Dement spent in fire towers. He typically searched for signs of fire from the seat of a helicopter.

The Centerville man’s career with the US Forest Service began in 1970. He has manned the Oates tower (since removed), the Buick tower, and occasionally worked at the Marcoot tower near Salem.

David routinely flew from March through May and again from September to mid-November. Dry seasons when trash fires got out of control also kept him busy.

As fires, or “smokes,” were called in from different locations, David and crew would fly to them and coordinate the locations of the fires by township, range, and sections.

He recalls a big fire on a windy Easter Sunday in 1977. After coming home from church, David helped patrol the 800- to 900-acre area because it was too windy to fly. He and crews worked together to do whatever it took to get the fire out—whether it was raking, running a bulldozer, or spotting.

“You didn’t get to come home until the fire was out,” he says.

Times have changed for fire spotting, David notes. “Fire monitoring is almost completely done by aircraft now,” he says.

FIRST LOOK

When Michael Bill started with MDC, he lived in a residence at the Coot Mountain fire tower, above the confluence of the Current and Jacks Fork Rivers. Currently the forestry district supervisor for the Eminence district, Michael says fire towers are still useful in his district when the forest fire threat is high, usually a few days a year.

Just this past spring, Michael says, he was returning from a meeting and heard radio traffic of a report of a wildfire in a remote area in northern Shannon County on the Sunklands Conservation Area. He was nearby and climbed the Shannondale tower. From the tower, he could see the fire and provide a bearing from the tower location, which gave the dispatcher a specific location. Michael’s tower view also provided an estimated size and movement and the best route to access the fire. The fire burned about 40 acres but could have been much larger had it not been for early detection help from the fire tower, Michael says.

“Our district works on the incident command system,” he says. “This allows us to organize resources quickly and work effectively as a team during wildfire suppression operations.”

PHONE SPOTTERS

Chris Mahan, a forestry and wildlife crew leader in Eminence, has watched the use of fire towers decline since he joined MDC in 1994. The seasoned tower operator has logged many hours at Coot Mountain, Deer Run, Flat Rock, Panther Hill, Shannondale, and Summers-ville fire towers. Yet this spring, he notes, he spent just three hours in the Flat Rock tower, an area where towers might have been manned 40 to 50 days a year in the past.

People today use cell phones to report wildfires, Chris says. When fire calls come in to Shannon County dispatch, the information is passed on to the forest district staff. Firefighters respond if they have an exact location. If not, two crew members head to two different towers—such as Flat Rock and Coot Mountain—to take measurements to pinpoint the location of the fire. A dispatcher then cross-references the two towers’ information to determine the fire’s location so responders can drive directly to it.

“It is a neat system that takes the guesswork out,” Chris says. “It makes your time more efficient.”

He adds that although the fire tower system is old, “It works well because you can pinpoint a fire down to a quarter section. It’s amazing how well it works. Fire towers were a great tool for what they were initially intended for,” Chris says.

He started his career with the generation of professionals who fought forest fires the old-fashioned way. “It was such a great time,” he says, “and it was an honor to learn from those individuals.”

These fire lookout towers are accessible to the public. Signage at each tower site indicates if it is open or closed for climbing. Search online by name to find a map from the Missouri Department of Conservation. View a map of all fire towers—past and present—at FireLookout.org.

CA = Conservation Area

- Blue Slip Towersite, near Norwood

- Cabool Towersite

- Camdenton Lookout, Camdenton Conservation Service Center

- Coot Mountain Fire Tower, Rocky Creek CA

- Deer Run Lookout, Current River CA

- Dixon Towersite

- Doniphan Towersite

- Flat Rock Lookout, Angeline CA

- Fort Leonard Wood Towersite

- Freeburg Towersite

- Garwood Fire Tower, Clearwater CA

- Houston Towersite

- Indian Trail Lookout, Indian Trail CA

- Keysville Towersite, near Steelville

- Montauk Towersite, near Salem

- Mountain View Towersite

- Panther Hill Fire Tower, Logan Creek CA

- Perry Towersite, near Perryville

- Roaring River Fire Tower, Roaring River State Park

- Rosati Towersite

- Rocky Mount, now at Runge Nature Center, Jefferson City

- Squires Towersite

- Stegall Mountain Fire Tower, Peck Ranch CA

- Summersville Towersite, Gist Ranch CA

- Thomasville Towersite, near Mountain View

Related Posts

108 Missouri Wineries

On December 11, 2012, state officials announced that there were now one hundred and eight commercial wineries operating in Missouri.

Notley Hawkins Documents the Flooding in Mid-Missouri

Photographer Notley Hawkins captured images of the historic flooding in mid-Missouri with his camera and drone. Plus, learn how you can assist in relief efforts.

Pickleball Is Taking Missouri By Storm

It took about a decade for pickleball to sweep Missouri. With more than 100 locations developed since 2010, Missouri might just have the fastest-growing pickleball community in the country.