The odds have been against most present-day Missourians learning much about the first people to occupy this land. Their history classes don’t dwell on the subject. The ancestors of nearly everyone in Missouri came from someplace else and arrived relatively recently, so they had no stories to pass on about Indian life. The tribes themselves, which passed down their history orally, are long gone from here—an exodus wrought by disease, government treaties, and forced assimilation. So it has been easy for modern Missourians to overlook the legacy of the region’s earliest residents.

But they were here.

In fact, Carl H. Chapman, acknowledged father of Missouri archaeology, wrote that indigenous societies could well have existed in the region for as long as 12,000 to 14,000 years before the arrival of the Spanish, French, and English. The earliest appeared at the end of the last ice age and hunted mastodons for food. Over the millennia, they fired their vessels, chipped their tools and weapons from stone, hunted, planted and gathered their food, wove and sewed fishnets and clothing, worshipped, studied the skies, painted images on blus and carved them into boulders, and traded and warred with other groups.

They didn’t just live in what is now Missouri. They reigned over it. And though it’s not easy to find, they have a story.

“History exists for them,” says Jim Duncan, archaeologist and former director of the Missouri State Museum. “It is recorded in their oral traditions and by the archaeological evidence.”

Archaeologists who study that evidence have determined that there were four specific geologic periods, the last of which was the Mississippian. It began around 1,000 years ago and lasted roughly 600 years, until Europeans first made their presence known. Much of the information we have regarding the lifestyles of the indigenous peoples of this period comes from artifacts, as well as their still vibrant oral traditions.

It was during the Mississippian period that the construction of permanent villages became widespread. Far from the earlier random scattering of huts, some towns grew quite large and were fortified against incursion. And as with the Indian cultures to the south and west, these towns contained temples, plazas, and celestial observatories. By the 13th and 14th centuries, however, these communities began to decline and disperse. In time, two indigenous groups emerged, bringing with them their own customs and technology. One group called itself Wazhazhe—“Children of the Middle Waters.” That name, however, was later mispronounced by the French, and this tribal group has been known ever since as the Osage.

The Osage

There are as many theories on where the Osage originated as there are points of the compass, and as historian Kristie C. Wolferman, author of The Osage in Missouri, says, “The debate … may never be resolved.” According to Osage oral tradition, the tribal group moved to the lands of presentday Missouri from the Ohio Valley as part of a larger group of Dhegiha-speaking Sioux, which included the Omaha, Quapaw, Ponca, and Kaw, or Kansa. The Osage were a semi-nomadic prairie culture, and successfully combined hunting, growing, and gathering. When the tribal groups splintered o and moved in dierent directions, the Osage established what authors Gilbert Din and A.P. Nasatir described in their book, The Imperial Osages, as “semi-permanent settlements … on the upper Osage River, the drainage of the Lamine River, and the south bank of the Missouri River.”

Over time, the Osage carved out a kingdom for themselves, and the land they claimed was vast. Early Missouri historian Louis Houck writes: “The territory from the Great Bend of the Missouri south to the waters of the Arkansas and east toward the Mississippi was the country of the Osages for several centuries before the advent of the Europeans. Here was their hunting ground. Over the high plateaux of the Ozarks and in the deep valleys cut through the plateaux by water they reigned as masters.”

Houck waxed poetic in describing the beauty of the tribe’s surroundings, many of which are reflected in the paintings of the first white artists to visit the West:

“On the banks of the pellucid streams meandering through the narrow villages, overhung by fragrant trees, with a background border of abrupt and picturesque hills or perpendicular clis, they raised their lodges. … Attracted by the water, countless bison roamed in the high prairie grass in summer, and in winter found shelter in the deep valleys from the rude north winds.”

To early French explorer Étienne Veniard de Bourgmont, it was “the finest country and the most beautiful land in the world; the prairies are like the seas and filled with wild animals … in such quantities as to surpass the imagination.”

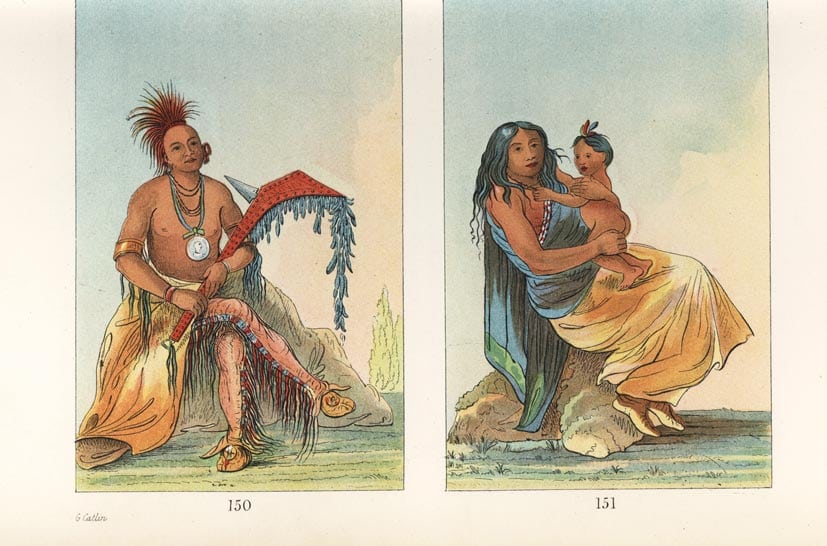

If Hollywood were to cast for a film about an early Missouri tribal group, it could not improve upon the historical reality of the Osage. During Missouri’s 1921 centennial observances, Walter B. Stevens, president of the State Historical Society, wrote that the Osage were “peculiar to and historically native to Missouri … and well might any state be proud of having produced such perfect physical specimens.” Of all the tribes to inhabit the region, the Osage were by far the most visually impressive. George Catlin, who studied and painted the Indians of nearly 70 tribal groups in the 1830s, described them as “the tallest race of men in North America, either of red or white skins.”

Various chroniclers and eyewitnesses have stated that few Osage stood less than 6 feet in height, while many reached a well-proportioned 6½ or 7 feet tall. In his History of Early Reynolds County Missouri, James E. Bell attributes their height, strength, and physical courage to tribal marriage practices. “The … mightiest warriors got the girl plus all her sisters.”

Michael Dickey, historian and site supervisor of Arrow Rock State Historic Site, expands on the Osage marriage practices: “The strongest and most beautiful girls of the leading families were married to proven warriors of unquestionable physical fitness. In this way they had a form of ‘selective breeding,’ which promoted the tribal ideal of tall and physically fit men. Men who were weak or displayed cowardice in war were forced to wear women’s clothing and refused the right to marry.”

The Osage were a clan-based tribal group, and the villages themselves were structured accordingly. The Tzi-shu, or Sky People, lived on the north side of the village, while the Hunkah, or Earth People, lived on the south. The Sky People were the civil leaders, and the Earth People were the leaders in war. Each of these two “moieties,” or ritual groups, had its hereditary chief, with subchiefs under him.

The life of the village was structured within a rigid, tradition-based system of self-government. And although the chiefs were acknowledged as tribal leaders, they and the rest of the tribe deferred to the Ne ke a shin ka (the “Little Old Men”), an elite body of elder sages, for moral and spiritual governance and adherence to tribal traditions. Devoted to meditation and study, the Little Old Men kept alive the origin stories of the tribe, describing how the Osage descended from heaven to create a life on the “Sacred One”—Earth.

A wide street separated the various clan groups; the chief’s lodge sat in the middle. The street ran east to west through the center of the village, laid out to follow the path of the sun, the giver of life. The rising sun brought a new day and, symbolically, life. As it traveled a path to the west, the setting sun symbolized day’s end, and with it, death—a crossing to the other side. This was the path that all life must travel, and it was a constant reminder to the Osage of their mortality before Wahkondah, the Creator.

Their lodges were solidly built in rectangular, oval, or circular shapes. In 1806, explorer Zebulon Pike visited an Osage village and described the sophisticated construction of the lodges, each of which generally held 10 to 15 people.

Zebulon Pike described Osage lodges: [They] are generally constructed with upright posts, put firmly in the ground, of about 20 feet in height, with a crotch at the top; they are generally about 12 feet distant from each other; in the crotch of those posts, are put the ridge poles, over which are bent small poles, the ends of which are brought down and fastened to a row of stakes of about 5 feet in height; these stakes are fastened together with three horizontal bars, and form the flank walls of the lodge. The gable ends are generally broad slabs and rounded off to the ridge pole. The whole of the building and sides are covered with matting made of rushes, of two or three feet in length, and four feet in width, which are joined together, and entirely exclude the rain … At one end of the dwelling is a raised platform, about three feet from the ground which is covered with bear skins, and generally holds all the little choice furniture of the master, and on which repose his honorable guests. They vary in length from 36 to 100 feet.”

In the middle of each lodge was the fire—some houses featured two or three fire pits, depending on size—that served for heat, cooking, and social functions. Holes in the roof allowed smoke to escape. Women were responsible for the cooking and several other arduous tasks. This practice led one early observer to write: “Their females perform the labor. The men do the hunting, go to war, and much of the time have nothing to do, while the laborious wife or daughter packs wood across the plain or brings water or plants corn and the like … in short, does all the drudgery, while the men spend their leisure time in smoking and diversion.” Arrow Rock’s Michael Dickey takes exception.

“Bear in mind, this is a European perspective, and such comments were basically used to denigrate the Osage and other Indian men,” he says. “The belief was, if they did not behave like New England farmers, they were no good. This attitude helped fuel Manifest Destiny and justify poor treatment of native peoples.”

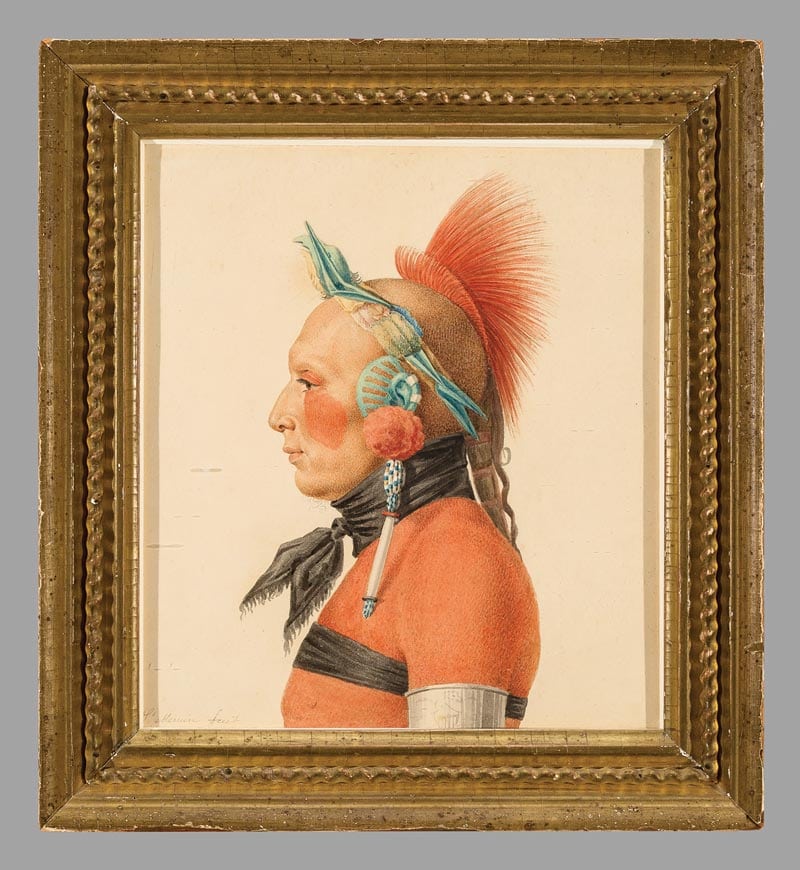

The Osage were fastidious about their appearance, and both men and women wore a variety of facial and body adornments fashioned from bone, wood, copper, stone, and seeds. Both sexes painted their bodies with symbols, using multicolored dyes derived from various oxide-based clay deposits. Some bore tattoos. While the men used the chest and shoulder as their canvas, often displaying images of their success in battle, the women sported tattoos on their chest, back, and arms, but with a different message. Louis F. Burns, author of A History of the Osage People, wrote, “These were all symbols of peace and life, since adornment for women forbad symbols of taking life.”

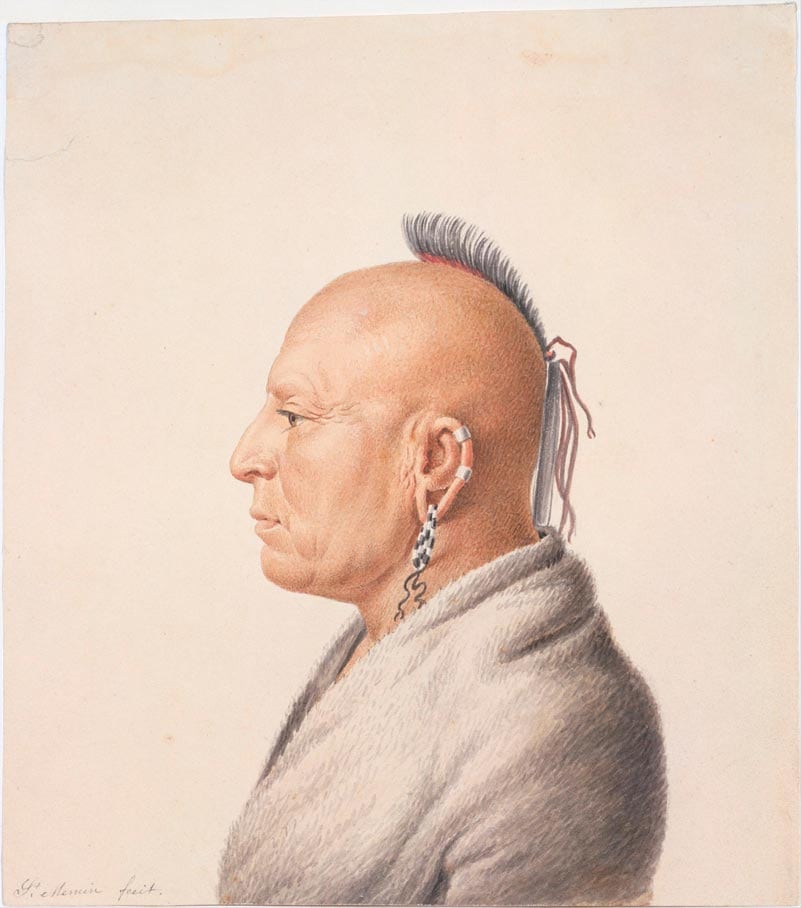

The men shaved their eyebrows and heads, leaving only a well-trimmed roach or scalp lock at the top, which extended down the back in a long tail. The women wore their hair long, with a red-dyed part running down the middle, symbolizing the path of the sun, giver of life. At their first exposure to Europeans, the Osage were taken aback by the hirsute countenance of the newcomers. They likened the Europeans’ bearded aspect to that of the black bear, and referred to them scornfully as “Heavy Eyebrows.” The pretrade-era Osage dressed in clothing made from the skins of the animals available to them: deer, elk, bear, and buffalo. In temperate weather, the men wore deerskin breechcloths and moccasins, adding hip-high leggings and fur robes in the colder months. The women, Burns writes, wore wraparound skirts, while “another deerskin was fastened over one shoulder and fell below the opposing arm.”

Aside from their physically prepossessing appearance, the Osage were fiercely warlike, ready to fight with any tribal group that threatened their domain. Proficient in the use of bows and arrows, lances, knives, clubs, and tomahawks, they used them in battle as well as in the hunt for food and skins. The Osage waged various types of war, from the nonlethal “counting coup”— simply touching a live enemy—to outright slaughter. Dickey writes: “You could judge the level of warfare by the paint worn by the men. Basically, it was not healthy to be around Osage men who were wearing black paint.”

Some historians have estimated the Osage population before first contact with Europeans at between 4,000 and 6,000; whatever their number, it was sufficient for them to maintain control over most of what is modern-day Missouri, Arkansas, Oklahoma, and Kansas.

Other tribal groups feared them. Grant Foreman, author of Indians and Pioneers, The Story of the American Southwest Before 1830, described the extent of their forays: “North of the Arkansas River … was the home of the Osage, a warlike, aggressive tribe of Indians who ranged … from the Missouri to the Red River and from the Mississippi to the Rocky Mountains on their hunting and marauding expeditions … They had few friends … From the earliest known history the Osage were at war with most of the surrounding peoples, and … were, in fact, the scourge of all the tribes within hundreds of miles.” When white people arrived, the Osage turned their attention to them as well, and the depredations visited upon these interlopers would engender panic across the western frontier.

The Missouria

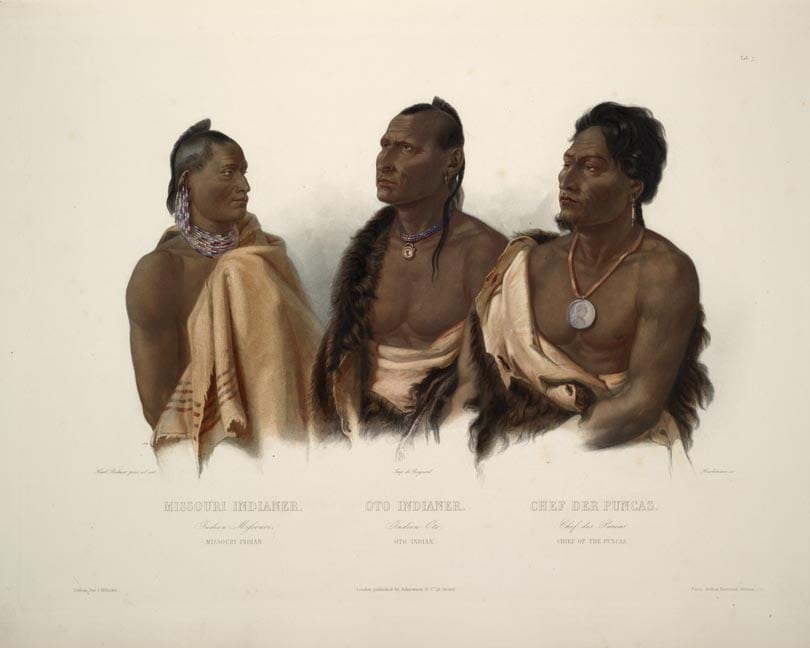

The second tribal group to settle the region we know as Missouri called itself the Niutachi. Its members were also of the Sioux nation but spoke the Chiwere-Siouan tongue, as did such related tribal groups as the Ioway, Otoe, and Ho Chunk. In the Chiwere language, the name breaks down into three parts: “Ni,” or water; “ut a,” or coming together; and “chi,” meaning to dwell. Loosely translated, the name means “People of the River Mouth.”

Apparently, this information was miscommunicated to the early Europeans. In the late 17th century, when French explorers paddled down the Mississippi to the raging, muddy mouth of what is now the Missouri River, they asked their Peoria guides who these river-dwellers were. Misunderstanding the question, the guides—who in all likelihood didn’t know the tribe’s name—described them as “Wemihsoori” or “Mihsoori,” roughly meaning “people of the wooden (or, dugout) canoes.”

The French initially spelled the name their guides had given them as “Ouemessourit” (pronounced, “Weh-misoo- ree”; the “t” is silent), and they wrote it on their maps as the Niutachi’s tribal name. Despite the fact that the indigenous name for the river was “Pekitanoui,” they simply called it the River of the Ouemessourit, and—after countless spelling variations— the Missouri. As Dickey says, “Indian tribes were usually called by the names Europeans put on a map, regardless of whether they were correct. In those days, once something found its way onto a map, it became history.” The explorers paddled on without entering the roiling mouth of the muddy Missouri, or meeting this tribe living on its banks.

The first identifiable settlement of the Missouria, as today’s Niutachi descendants call themselves, was at the Pinnacles, in what is now northern Saline County. Van Meter State Park encompasses some, but not all, of this village site. The Missouria lived here from roughly 1300 to the early 1700s, when the population moved its village some eight miles west to Gumbo Point. Here they remained—until tragedy struck.

For years, the Missouria had been engaged in intertribal warfare with the Sac and Fox. Sometime between 1790 and 1800, their sworn enemies laid an ambush, killing most of the Missouria population.

German explorer Maximilian, Prince of Wied, described the slaughter of the Missouria that he saw on his trek through the region: “We were at the part called Fox Prairie, [where] the Saukie and Fox Indians … formerly attacked, and nearly extirpated the tribe of the Missouris … The Missouris came down the river in many canoes, and their enemies had concealed themselves in the willow thickets. After the Missouris, who suspected no evil, had been killed or wounded with arrows, the victors leaped in the water and finished their blood work with clubs and knifes: very few of the missouris escaped.”

When shortly after the onesided fight, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark passed through the region, Clark, who referred to the tribe as “once the most powerful nation on the Missouri River,” reported only about 400 living tribal members. Unable to function any longer as an independent tribe, the survivors sought sanctuary by assimilating into other tribal groups. According to John Joseph Mathews’s exhaustive work, The Osages, Children of the Middle Waters, around 1801 the Missouria were taken in by—and absorbed into—the Otoe, Kansa, Ioway, and Little Osage, a division of the Osage nation.

The Sac and Fox attack was far from the only cataclysmic event to befall the Missouria. Beginning as early as 1700— when the population is thought to have numbered around 10,000—and extending for more than a century, they suffered prodigious losses from such European diseases as smallpox, measles, influenza, and cholera. By the time of the Sac and Fox ambush, the tribe had already been reduced to fewer than 1,000 people.

Attributing the scarcity of documentable evidence to a combination of white men’s diseases and near-annihilation by the Sac and Fox, archaeologists/historians Michael J. O’Brien and W. Raymond Wood write in The Prehistory of Missouri: “It is unfortunate that we know so little of the history and culture of this tribe.” Nonetheless, Dickey argues, “Enough information survives to provide some perspective on the Missouria’s place in history and an idea of their culture.” In addition to oral tradition and existing physical evidence, certain Missouria tribal traits and customs can be extrapolated, based upon similar cultural styles and practices of both the Chiwere- and Dhegihaspeaking tribes of the southern Sioux.

As was the case with most of their neighbors, the Missouria were hunter-gatherers who spent time farming. Semi-nomadic, they would plant their crops—beans, corn, squash—in the spring, using hoes hewn from bison scapulae, leave their villages to go on extended buffalo hunts throughout the summer, and return to harvest their crops in the fall. The fullness of their larders reflected the bounty of their crops, the availability of various species of nuts and fruit, and the success of the hunt.

The Missouria lived in frame dwellings of various types. Some were covered in woven reeds or rushes; others were overlaid with slabs of bark. Some of the lodges were elliptical in shape; others were round. After assimilating into the Otoe tribe, however, Missouria lived as did their hosts—in tipis or earthen lodges.

“We can assume that their style of dress was fairly generic,” Dickey says. “The men went shirtless in the summer, wearing only loincloths. Women sometimes went topless in the heat as well, while the children ran about in their natural state.” Hairstyles, especially for the men, were similar to those of the Osage—an adorned, trimmed roach at the top of the head. And as did the Osage women, the women of the Missouria painted the part in their hair red, to represent the path of the life-giving sun.

Missouria men were polygamous, but the women were allowed only a single mate. Yet women were not powerless and were essential to the well-being and preservation of the family, and the tribe. In fact, she owned the lodge and all it held, and possessed the right to divorce her husband. To attain a permanent separation, she simply had to throw his possessions out of the house.

As with all tribal groups of the southern Sioux, children were highly regarded and well cared for. Boys and girls played together until they reached the age of 11, when gender assumed a defining role in their upbringing and training.

The Missouria were a highly spiritual people who worshipped a single deity— Maun, the Earth Maker or Creator. Theirs was a clan-based society, with each clan springing from a benevolent spirit animal related to the Creation of the World. As with the Osage, each village was built upon an east-west pattern and divided into the Sky and Earth people. Dickey explains that this reflected the Missouria’s belief in the “duality and balance in the universe … natural events and behaviors occurred in pairs … night and day, winter and summer, earth and sky, life and death … good and evil, success and failure, war and peace, all balanced one another.”

Each village had a number of wa eghi, or headmen, who acted as leaders in such matters as war, religion, administration, and medicine. A hereditary position, headmen were looked to for guidance and direction and were required to possess courage, kindness, compassion, impartiality, and the ability to always light the proper course by personal example. Although the wa eghi were not chiefs per se—a distinction that would later confuse and confound European arrivals—they were singly and collectively responsible for maintaining the order of the community.

The social and religious systems of the Missouria, as well as those of the other southern Siouan tribal groups, were—in Michael Dickey’s words—“sophisticated and complex and produced a strong, vibrant social order in their lives. They lacked only the ability to write this information down.” Their social and religious mores survived for centuries through adherence to strictly observed oral tradition. Ironically, their oralbased culture led each consecutive group of arriving whites to view them as directionless savages whose existence, Dickey says, was “without structure or purpose in their belief systems and worldview.” Nothing could have been further from reality.

Epilogue

The two original tribes to hold the lands now known as Missouri flourished until the coming of the Europeans. In time, one of these tribes would lose its land, and the other would all but disappear. The millions of acres controlled by the proud and warlike Osage have long since been taken from them, through deliberately misleading and sometimes fraudulent government treaties and land deals.

There are no full-blooded Missouria alive today; the last one died in 1985. Two centuries after their ancestors were absorbed into other tribes, the remnants of the once-powerful Niutachi exist only within the amalgamated tribal group formally known as the Otoe-Missouria.

Nor were these two tribes unique. After the various land-hungry nations staked their respective claims on the seemingly boundless expanse they called the New World, no tribe that had long occupied or settled in Missouri would ever again claim control over itself or its old way of life.

Coming in September: “The Tribes of Missouri, Part 2”

The arrival of Europeans in North America had a devastating impact on the tribes of early Missouri. Their story continues, from the mid-16th century advent of Hernando de Soto’s conquistadors to the presidentially mandated mass expulsion of the 19th century that resulted in the infamous Trail of Tears.

Related Posts

7 Missouri Waterfalls

A haven for gorgeous scenery, the Ozarks is brimming with stunning waterfalls. April and May are great months to enjoy our waterfalls, as water flow is at its peak from spring showers.

Pickleball Is Taking Missouri By Storm

It took about a decade for pickleball to sweep Missouri. With more than 100 locations developed since 2010, Missouri might just have the fastest-growing pickleball community in the country.

Paddling 340 Miles on the Missouri River

From August 8 to 11, 450 crazy people will paddle down the Missouri River in canoes, in kayaks, and stand-up paddleboats—all competing against each other and themselves in the MR340 race.