Whether lying on a creek bank or peering through a telescope, people love to look at the stars. The night sky in all its vastness and majesty inspires us. We find evidence, if not proof, of eternity as we gaze in wonder at the innumerable lights.

By Anita Neal Harrison

“There is no bigger subject,” says Ralph Dumas, a director of the Central Missouri Astronomical Association board. “I first looked through a telescope when I was 10 years old, and I’ve been hooked ever since. I’m always learning.”

Missourians who want to learn about the wonders of our universe have ample opportunity. Dozens of observatories sit within our state’s borders. Although only a few are open to the public, astronomy lovers can access many of the private observatories by joining the appropriate astronomy club; visit www.astronomyclubs.com for a list. And anyone can view the heavens through powerful telescopes at these public observatories.

MORRISON OBSERVATORY Fayette, Missouri

First constructed in 1875, the Morrison Observatory houses an 1875 Clark refractor telescope. This astronomical artifact measures nearly seventeen feet long and has a 12-inch aperture. Its maker, Alvan Clark and Sons of Cambridgeport, Massachusetts, earned fame in the late 1800s as the best telescope maker in the United States.

The $6,000 telescope was purchased by Carr Waller Pritchett, director of the long-closed Pritchett School Institute in Glasgow, using a gift from Berenice Morrison. She pledged $100,000 to the construction of the institute’s observatory while viewing Ceggia’s comet with Pritchett. He used the state-of-the-art telescope to conduct celebrated research on the red spot of Jupiter.

Pritchett died in 1906, and in the next two decades, the observatory deteriorated from a home of scientific inquiry into a home for chickens. In 1926, Central Methodist College (now University) in Fayette sued the city of Glasgow for possession of the observatory. On June 1, 1935, after winning the suit, the college dedicated the new Morrison Observatory, built with the original dome, overlooking the Fayette city park.

Today, guests find several historical instruments besides the Clark telescope, including a Troughton and Sims Meridian Transit.

“It features an eight-inch refracting telescope and was used as a time standard for much of the Midwest in the late 1800s,” says Professor Larry Peery, who had served as the observatory’s director since 1979. (Dr. Kendall Clark is the current director. Professor Peery passed away.—Editor) “It was also used to determine stellar positions with good accuracy for the period.”

Modern instruments at the observatory include a computer-guided, 10-inch Schmidt-Cassegrain telescope.

“We can use this telescope for photography and digital imaging in addition to observing,” Peery said.

Central Methodist University generally welcomes visitors to the observatory at 504 Park Road, Fayette, every spring and fall. Check here for updates, or call 660-248-6383.

LAWS OBSERVATORY Columbia, Missouri

Laws Observatory was founded in 1853, when the University of Missouri built the first observatory west of the Mississippi. The observatory housed a refractor telescope with a 4 1/16-inch lens. In 1879, the university convinced the failing Shelby College in Shelbyville, Kentucky, to take this rather small telescope along with five hundred dollars in exchange for a seven-inch Merz and Sons refractor. After making the deal, the university realized it could not afford to transport and reassemble the larger telescope or to build a fitting observatory. So University of Missouri President Samuel S. Laws spent $2,000 of his own money to complete the project. In the early 1900s, Harlow Shapley began assisting the Laws Observatory director. This MU graduate later determined our sun’s position in the galaxy and our galaxy’s scale.

Unfortunately, by 1950, Laws Observatory had suffered terrible neglect. Many of the instruments were broken, and a leaking dome had led to the rotting of the Merz telescope’s wooden tube. In 1954, the Central Missouri Amateur Astronomers, now the Central Missouri Astronomical Association, restored the observatory and refitted the telescope with an aluminum tube.

Laws Observatory moved two times on the MU campus before moving in 1966 to the then-new Physics Building. Since its opening, the Physics Building has featured a 16-inch Celestron Schmidt-Cassegrain telescope installed in a rooftop dome. Today, the roof also holds two 10-inch Schmidt-Cassegrains, a computerized telescope, and a six-foot radio dish that allows the public to hear cosmic noise from outer space.

In addition, guests find a display room with antiques and NASA collectibles, including autographed photos of mission control personnel from Houston, past and present. There’s also a “virtual observatory,” a computer lab where they can “look through” remote telescopes and even steer telescopes thousands of miles away.

“We keep people entertained even on a cloudy night,” says Ralph Dumas, a director of the Central Missouri Astronomical Association board, whose work with CMAA includes volunteering at Laws.

Laws Observatory, in the MU Physics Building off College Avenue, is open to the public year-round, every Wednesday (weather permitting) from 8 to 10 PM, except on holidays.

EAST CENTRAL COLLEGE OBSERVATORY Union, Missouri

A one-column article in the November 1942 Scientific American tells how East Central College Observatory got its start. The Rev. Earnest L. Coates built the observatory in Wellston, a suburb of St. Louis. Two decades later, an astronomy group from the McDonnell Douglas Corporation moved the observatory to member Del Scott’s home in O’Fallon, where it stayed until the early 1990s. Scott then gave the observatory to the Eastern Missouri Dark Sky Observers.

Wanting to share the observatory with the public, EMDSO club officers Rick Schwentker and Jerry Kelly took a proposal to East Central College: If the school would provide land for the observatory, pay its electric and insurance bills, and maintain building security, EMDSO would refurbish the observatory, move it to school property, and offer it to East Central College as a gift. The club would also host free public stargazing sessions.

Schwentker and Kelly spent the next few years raising funds for construction and contributing sweat equity to make that plan a reality. They dedicated the East Central College Observatory in April 1997 on Astronomy Day.

Telescopes located at the site include one 10-inch, two eight-inch, and two six-inch homemade scopes plus a four-inch refractor. EMDSO members bring additional telescopes on public viewing nights.

EMDSO also has access to two large telescope observatories built and funded through members and private investors. One features a 40-inch and one a 30-inch-diameter mirror Newtonian Dob Mount telescope. Visits to these private observatories are by invitation only, but Schwentker says securing an invitation is as easy as asking a club member for one.

The East Central College Observatory, 1964 Prairie Dell Road, Union, Missouri, holds occasional stargazing events. Check here for updates.

BAKER OBSERVATORY Springfield, Missouri

In 1974, Southwest Missouri State University (now Missouri State University) Professor of Astronomy George Wolf began looking for land and funding for an observatory. Three years later, he chose a piece of property that William and Retha Stone Baker offered the university for free in a dark area of Webster County. The Bakers felt, and Wolf agreed, the university’s observatory should be located near Marshfield, the birthplace of astronomer Edwin Hubble.

Baker Observatory was officially dedicated in 1983. Equipment included a few eight-inch telescopes, a 14-inch telescope, and a 16-inch research telescope on permanent loan from Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in Chile. Wolf learned about the availability of the 16-inch telescope while visiting the Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory to study stars in the southern sky.

From 1989 to 1999, the main research instrument on the telescope was a computerized Photometric CCD research camera system. Instead of using film to receive incoming light, CCD cameras use a small, rectangular piece of silicon called a charge-coupled device. In 1999, lightning struck the observatory and damaged the original CCD camera system. The university replaced the damaged equipment with a new state-of-the-art Princeton Instruments CCD camera system.

Baker Observatory, 1766 Old Hillcrest Road (off Route 38 in Webster County near Marshfield), opens to the public only once in the spring and fall during its advertised NASA Nights. Check here for updates.

This story originally ran in the October 2006 issue of Missouri Life. No original quotes or sources have been changed, but contact information or other info in parentheses and italics for each observatory was updated in March 2023.

Related Posts

Hunter Forced to Watch Bambi

On December 17, 2018, a hunter from Barton County was sentenced to watch Disney’s Bambi repeatedly during his year-long prison sentence after being convicted of killing hundreds of deer illegally.

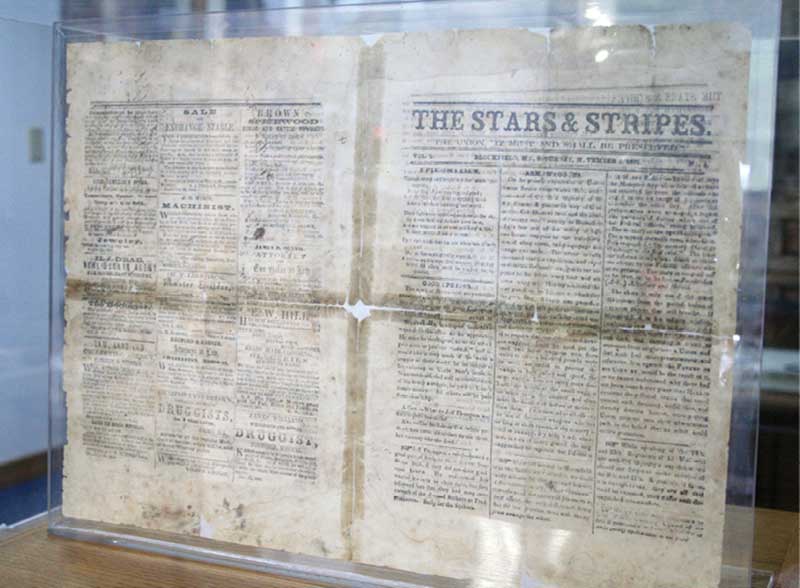

Relics: Stars and Stripes Museum and Library

Since the first Stars and Stripes was printed in Bloomfield in 1861, the Department of Defense designated Bloomfield as the birthplace of the Stars and Stripes newspaper. The Missouri Stars and Stripes was printed only once during the Civil War. It wouldn’t see publication again until World War I, when it was an eight-page weekly. Publication stopped after WWI, then for the first nine months of World War II, it was restarted.

Where You Can Watch Missouri Life TV

Missouri Life TV is back with its fifth season.