This article originally appeared in the March 2021 issue

On October 3, 1861, a Union Army officer, William Black, wrote a letter to his mother from his campsite in Boonville.

“I write in haste, as a boat leaves here this PM,” he explained, before describing Boonville as “a very pretty place,” with a cemetery that contained “the prettiest monument I ever saw; a statue of twin sisters in marble, some four feet high.”

Having read this intriguing endorsement, I felt compelled to visit Boonville’s Walnut Grove Cemetery to see this sculpture. As I entered the graveyard, I spied the monument’s marble figures on a pedestal across the wooded burial ground, white against the red-brown leaves of the November afternoon.

I was struck by the powerful simplicity of the monument. Two women stand together, hand in hand. One wears a modest short-sleeved dress and holds the waist of her companion. The other wraps a comforting arm around the first figure’s shoulders. William Black can be forgiven for thinking that the sculpture represented twin sisters, but close observation reveals that the second figure wears ancient Roman clothing that identifies her as a personification of an idea rather than a representation of a mortal. This maiden in classical garb is likely an allegorical figure of Faith, looking skyward, as described in the inscription on the pedestal:

“Here lies our sister Kate

Here Love her sacred vigil keeps

O’er dust that in long silence sleeps.

But Faith looks up with eager eyes

To meet her spirit in the skies.”

“Kate” is Kate Tracy, and the figure in nineteenth-century dress is likely a portrait of her. She is further identified on the rear of the monument’s pedestal, where her relationship with the memorial’s sponsors is better explained in the inscription:

Erected by the Adelphai

In Memory of

Kate

Only daughter of

Joshua L. and Catherine G. Tracy

Who died May 16th A.D. 1854

Aged 17 years

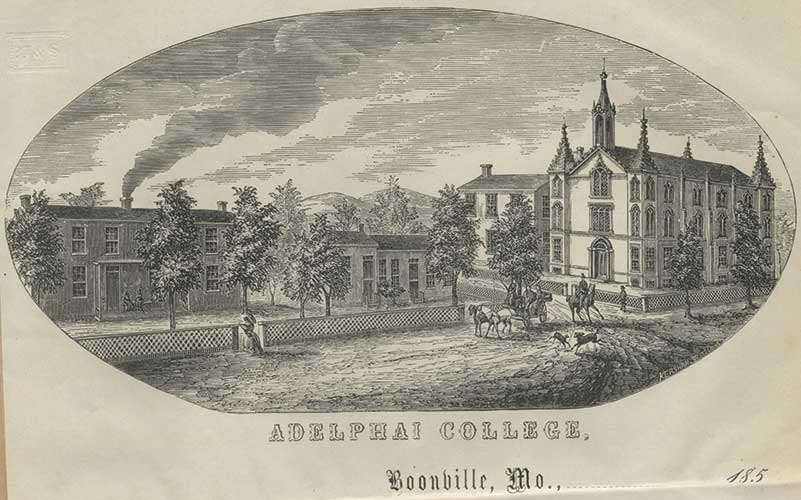

As the inscription indicates, Kate Tracy was the child of Professor Joshua Tracy, the headmaster of Boonville’s Female Collegiate Institute, a boarding school founded in 1840 that had earned a distinguished reputation as an educational institution for young women in Missouri and beyond; in 1854, girls from Texas, Virginia, and Vermont were attending the school. The Adelphai was a literary society formed by the institute’s elder students in 1850. This association’s constitutional object was “the improvement of its members in mind, manners, and moral sentiments,” and the group held weekly meetings that encouraged discussion, composition, and rhetoric. To confuse matters, the Female Collegiate Institute became the Adelphai College in 1855, but in the context of the Kate Tracy Monument “the Adelphai” refers to the literary society.

“Adelphai” literally means “sisters” in Greek, and the membership of this organization formed a sisterhood of scholarship, sharing a library of more than six hundred volumes, and regularly exhibiting their talents by reading essays to one another and holding friendly debates at their meetings. In 1854 they began publishing The Iris, a literary magazine with the stated mission of gratifying “the wishes of a few scores of school girls and their immediate friends, who desire to preserve a record of each other’s thoughts.”

I located issues of The Iris in several Missouri libraries, as well as in the libraries of Yale University and Smith College in Massachusetts. I examined the issues preserved at the State Historical Society of Missouri in Columbia and noticed that the figures represented on some of the covers resembled those on the Kate Tracy Monument.

The Iris’s cover artist, St. Louis printmaker James M. Kershaw, pictured two classically clad maidens—likely personifications of the arts—with their arms wrapped around one another. Their presence reflects the sophisticated aspirations of the Adelphai, and the figures’ intimate embrace may have served as an emblem of the organization’s sisterly bonds. It is tempting to suppose that this cover imagery played a role in the Adelphai’s decision to commission a sculpture of two female figures in a supportive embrace to mark the burial place of their dearly departed “sister,” Kate Tracy.

Indeed, Kate was one of the Adelphai’s founding members, and she was corresponding secretary for the organization when she died. A few months before that fatal day, on December 22, 1853, Kate read an essay to the membership of the society that was published in The Iris in 1854, shortly before the death of its author. In the essay, Kate discussed her recent tour of America’s eastern states and spoke of visiting Niagara Falls and Plymouth Rock. She declared that although she treasured her memories of these places, she preferred to be with her Adelphai “sisters” in Boonville:

I would rather dwell in the warm light of love, than amidst the cold but gilded splendors of the fashionable world. Mrs. President, pardon my seeming vanity in speaking so much of my personal experience. Let me rather turn to our own little world the Adelphai. With our Society it has been a year of uninterrupted pleasure and profit. Death’s wing has cast no shadow over our little band, and though we are scattered to and fro, yet our hearts are bound together by a tie as strong as love, and lasting as life.

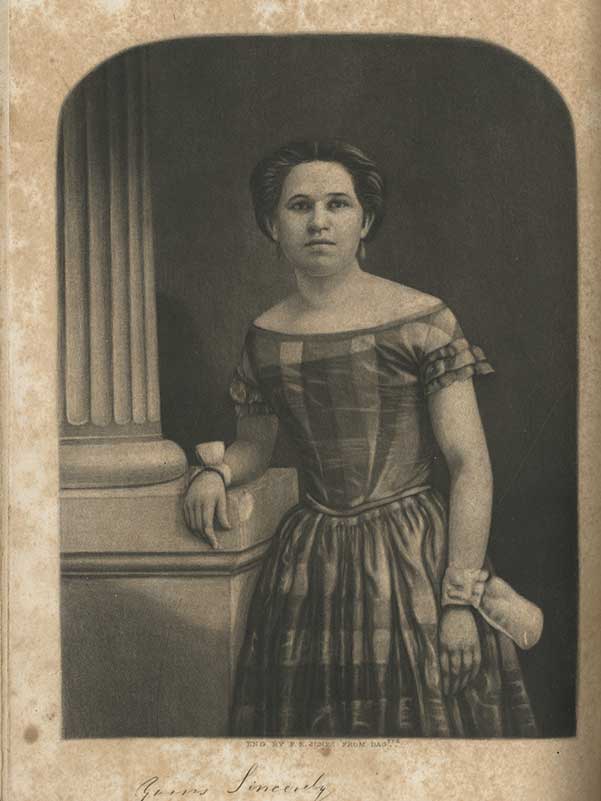

After Kate’s death on May 16, 1854, of cholera, the Adelphai published an issue of The Iris dedicated to her memory. The issue began with an engraved portrait of Kate by P. E. Jones. The young woman is shown in a simple patterned dress looking calmly out at the viewer. After seeing this portrait, few will doubt that the round-faced marble figure on the Kate Tracy Monument is Kate herself. The stone effigy even wears the same distinctive dress, with its three-tiered ruffled sleeves, that Kate wears in the engraved portrait.

Within the memorial issue of The Iris, the editor writes of the deep feelings Kate’s death inspired both within and without the Adelphai:

She left us on a short visit to her friends in St. Louis, but scarcely had the wind obliterated her retreating footsteps, until the lightning whispered back, “Kate is dead!” The solemn whisper spread from ear to ear, along the streets and through the dwellings of the city, and cheeks were blanched and eyes were dim with tears. … In the morning we bore her away to her last resting place, and a multitude of old men and matrons, young men and maidens, youth and children, came together to honor her sepulture, and drop tears and flowers into her open grave.

At the end of the issue, two poems written by Kate’s “sisters” are included in the magazine. A passage from a poem by a woman identified only as Annie, titled “To Kate in Heaven,” reveals the intensity of her sisterly love:

Oh, shall I never clasp again

Thy dear, dear hand in mine

Or gaze into thy deep dark eye—

That earnest eye of thine?

How oft in dreams I see thee, Kate

As in days of yore thou wert

And a joyous thrill steals o’er my soul

As I press thee to my heart. …

As the weary dove moans for its mate

Alone in the greenwood tree,

So dearest one, since thou hast flown,

My sad heart sighs for thee,

We would not break thy gentle sleep—

Though near thee oft we rove

Peaceful be thy slumbers, Kate,

Low in Walnut Grove.

Finally, Bettie Ragland describes the feelings of the Adelphai sisters when they met without Kate present:

Companions of our mystic tie, are ye

All here tonight? Rank after rank, in full

Array your numbers stand, but is there not

Some loved one absent? Why wear that badge

Of woe? Whence comes the stifled sigh, that tear

Of grief, that brow of agony? Alas! They tell

Too true, of blasted hopes, and heart strings crushed

Forever!

The deep grief and love manifested in these writings is also embodied in the Kate Tracy Monument. Unfortunately, I found no further documentation, apart from the monument itself, to help me better understand the details of the marker’s commissioning. We know that it took the Aldelphai until 1855 to erect the memorial and that the sculptor was highly skilled. It’s likely that he (or she) came from St. Louis where the Adelphai had contacts, and that the erudite women of the organization chose the allegorical subject.

Additional aspects of the memorial’s history remain a mystery, even as the monument provides us with a fascinating window into an event that took place over 165 years ago—when a group of talented young women who actively promoted female scholarship mourned the passing of one of their own.

Photos // Joan Stack, Library of Congress

Related Posts

Revitalizing Missouri Downtowns

Here’s how Missourians are working together to revitalize downtowns across the state.