Sedalia artist Doug Freed uses light, color, and form to inspire contemplation.

Heading south on Highway 65 toward Sedalia, the home of the Missouri State Fair, I am on my way to the historic district of this old railway town to visit the studio of Doug Freed, a Missouri painter represented in galleries across the state and nation.

Missouri art lovers may know Doug as the former director of the Daum Museum of Contemporary Art in Sedalia. Doug helped found this extraordinary museum, where visitors may be surprised to find world-class works by artists such as Helen Frankenthaler, Richard Diebenkorn, and Robert Motherwell. Doug was a close friend of the museum’s namesake, Dr. Harold F. Daum, who had amassed an impressive art collection over the course of many years. Harold asked Doug to help plan a museum founded on this collection, and the artist oversaw its development from 1999 until its opening in 2002.

Doug continued as the museum’s director until 2008, enhancing the collection with funds provided by Harold for that purpose. The Daum is now considered one of the premier museums dedicated to contemporary art in the Midwest.

I am tempted to make a stop at the Daum on my way into Sedalia, but I decide to go straight to Doug’s studio. I am eager to talk to him face-to-face about his long history in the national art scene and his experiences both as a color field painter in the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s and as a creator of atmospheric landscapes more recently.

Doug’s studio is in a historic building on Sedalia’s East Main Street, with a beautiful old storefront. I look through the antique windows to see his spectacular large canvases lining the walls. Doug greets me with a smile and welcomes me into his studio, which he shares with his son, the respected painter and author Damon Freed. Eager to show me around, Doug points out recent artworks hanging near the windows before taking me to the back to see his work area.

Here I see the computers, shelves, and papers one would expect to find in a typical business office, but many of the walls are covered in plastic sheeting. I see traces of paint from the artist’s most recent art works on some of this sheeting and mention this to Doug.

Past and future on his mind.

The artist laughs and tells me that the colors on the plastic serve to document his studio history, reminding him of the last few pictures he has made in various locations. He explains that he changes the plastic when it becomes too covered in paint. I also see photographs affixed to the plastic in some areas. Doug points out that these represent recent paintings and ideas for future paintings. He adds that he likes to think about his creative past and future as he works in the present.

Doug’s work has changed dramatically over the course of his fifty-plus-year career. He first came to my attention when I was an art history student at Mizzou in the 1980s, where I saw his work at the University’s Museum of Art and Archaeology. At that time, Doug was working in a nonrepresentational style, creating multipanel artworks that consisted of several canvases, each covered in beautiful tonal layers of color. I ask him what attracted him to the idea of creating artworks made up of multiple, related panels, and he tells me he has always been interested in the visual relationships of painted triptychs and polyptychs of the Renaissance and Baroque eras. He also liked the sculptural quality of multipaneled artworks, and the way their spatial relationships encouraged viewers to compare and contrast their visual qualities.

Doug’s color field paintings made a splash nationally, and he was represented by Vorpal Gallery in New York City throughout the 1980s and 1990s. I am disappointed that he does not have any paintings from this period currently in the studio, but Doug takes me out to a small patio in the back where two beautiful multipanel sculptures in metal are displayed. I instantly recognize the “Freed style” of multiple rectilinear forms arranged in interesting patterns, and we discuss how the natural corrosion of the material mimics some of the tonal qualities of his paintings.

Back inside, I ask Doug about his decision in the early 2000s to begin adding representational elements to his work. Many of his newer images are still multipaneled constructions, and fields of color remain an important element in all these paintings. Doug tells me that as he was working on non-objective paintings at the dawn of the twenty-first century, he began to see landscape elements in the compositions. He was drawn to the way these elements resonated with him, and he felt compelled to more fully explore the creative possibilities of working abstractly from nature.

‘Intrinsic power’ of nature.

The walls of the studio are covered with canvases depicting hazy vistas with open skies, woods shrouded in mist, and seascapes in which water and sky are separated only by a narrow horizon line. I notice that there are no traces of human activity in most of these images, and I ask Doug if he feels that the paintings have an environmental message.

He tells me that he does not put any conscious messages into his artworks, but he welcomes such associations. For him the images of land, sea, and sky have an intrinsic power.

I see an affinity between the universal purity of color, shape, and form in Doug’s early work and the tonal landscapes that represent the essential elements of nature. Doug tells me that he has always been interested in the idea of “the void” or empty space, and many of his nonrepresentational works had an atmospheric quality that some might compare to subtle shadows on a wall, or a sky illuminated by fading light. This interest in representing light and color in a material void continues to be an important element in Doug’s abstract landscapes.

My attention turns to Doug’s worktable, which stands against the wall. Everything is neatly arranged, and I marvel at the dozens of brushes inside a container on the table. I ask Doug about the materials he uses, and I am surprised to learn that he does not use a traditional artist’s palette. Instead, he prefers to use paper palettes, which can be ordered from art supply stores. These palettes resemble sketch books on which the artist mixes colors on the surface of specially treated white paper. When the surface is covered, he tears off the sheet, discards it, and begins working on the next page. This method provides the artist with a blank slate each time the palette is changed.

Doug has changed his method of applying paint over the years. When he was working on his non-objective paintings, he sprayed multiple translucent layers of color on top of one another to achieve subtle transitions of hue on the smooth surfaces of his canvases. He didn’t share the interest of some nonrepresentational painters in emphasizing the process of painting with obvious brush strokes and paint marks. Doug preferred to de-emphasize the mark-making process, and he found that spraying the paint onto his canvases effectively created the desired smooth and even surface.

All brushstrokes have meaning.

Today, the artist uses a different method to minimize the evidence of his mark making. He begins his landscape paintings in the traditional way, applying brushstrokes to the canvas to create an image. Sometimes he uses a scaffold to paint his large canvases, which can be over eight feet high. Once he has completed the picture, he takes a broad brush and sweeps it horizontally across the canvas, repeating this process until the entire image has been brushed. The brushing of the paint blurs the tonal contours between forms and creates a smooth, even surface for the entire painting. I find the process fascinating, in part because it ties Doug’s current work to the pristine canvases of his non-objective period, and because the act of brushing over the image reminds me of the way the mind brushes over lived experiences, remembering them in a somewhat blurry manner.

I notice that Doug prefers to exhibit his works without frames. He even signs the pictures on their outside edge, scratching his name into the wet paint. I see numerous paintings signed in this way on the studio’s painting racks. When displayed as intended, neither the frame nor the signature distracts from the formal beauty of the painting. Doug shares his official artist statement with me, which includes words that help elucidate his minimalist approach: “I do not want anything to distract from the illusion of depth,” he writes. “The compositions are about ambiguities of form and void, foreground and background, and surface and deep space.”

The artist has also written that he seeks to create images that inspire contemplation and explore the “ambiguities of physical and spiritual experiences of light … color and form.”

When I finally say goodbye to the artist, I realize I have a long drive ahead of me. I get in the car and drive north toward a stormy Missouri sky. As I am confronted with a Freed-like chromatic void, I think about Doug’s paintings and look forward to seeing more of his work in the future.

Related Posts

September 23, 1979

Lou Brock stole his 938th base after hitting his three thousandth hit.

September 26, 1820

Daniel Boone died at his home on the Femme Osage near Defiance.

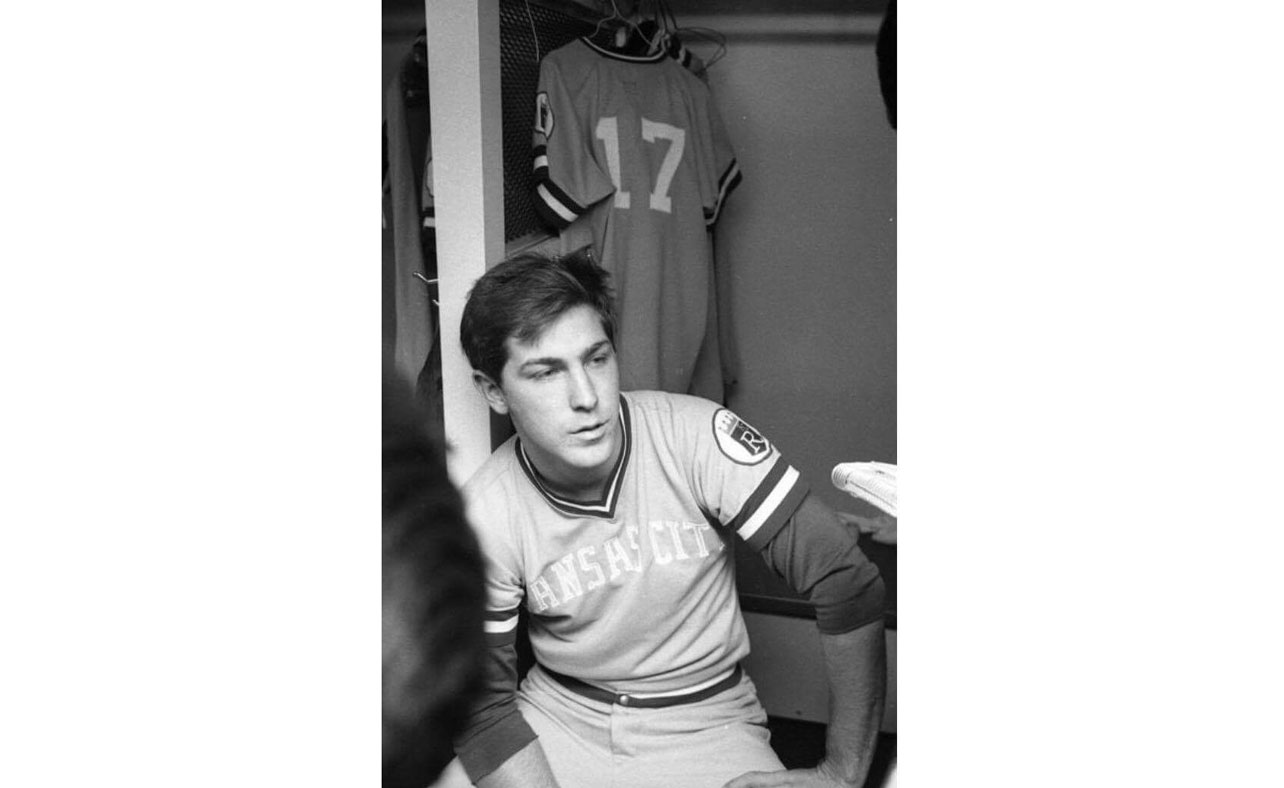

Mark Littell Shares His Wildest Stories

Country Boy is Mark’s second book, following his 2016 memoir, On the Eighth Day, God Made Baseball. Mark, who used to enter games to John Denver’s “Thank God I’m a Country Boy,” describes his latest work as a coming-of-age nonfiction story about how his character formed while growing up in Missouri.