Our writer became a soldier for a day at an event at Fort Leonard Wood, one of the models for Beetle Bailey’s Camp Swampy. Then cartoonist Mort Walker gave us an original illustration to accompany the story.

In honor of Missouri Life’s 50th anniversary, we’re digging into our archives. We loved this story by Cynthia Barnes, which appeared in the February/March 2000 edition. Much will have changed, of course, but we think you’ll enjoy tagging along with her.

Fort Leonard Wood, one of the models for Beetle Bailey’s Camp Swampy, is holding the first Be a Soldier for a Day event to give the media a good look at the army from the inside and I get to go! It sounds like loads of fun, although I don’t see how we’re going to learn much. We don’t even have to be on base until 0600.

Thursday, 0540

Seems the army has its own timekeeping system. Turns out that 0600 is six o’clock in the morning! I made it, but it’s cold and raining hard. I’m sure this will be canceled, but I’ll stick around until I can find a cappuccino.

0630

Lesson Number One: The army never cancels. Chief of Staff Colonel Larry Davis welcomes us (me and fifteen other reporters) with a big smile and a motto we’ll hear all day: “If it ain’t rainin’, it ain’t trainin’.” During our briefing, Major Derik Crotts, public affairs officer, gives us an overview of the base. Fort Leonard Wood trains more than fifty thousand soldiers a year. A class of 235 will be graduating later today, after nine weeks of basic training.

In addition to turning civilians into warriors, the Air Force, the Marines, and the Navy also send service members to Fort Wood for training in engineering, chemical defense, military policing, and other specialties. We’re given coffee — thank you, God — and a short lecture on organizational structure. Note to self: Being a brigadier general is definitely the way to go. Rainproof ponchos are distributed. Chic and flattering to every figure they are not. Out in the rain, we go. Oh, what have I gotten myself into?

0815

You may have seen the recruiting commercial that shows soldiers building a bridge. It looks like they’re having a pretty good time. Sergeant First Class Mark Morris hands out life vests while giving the safety lecture. We will be attaching three twelve-thousand- pound metal bays (rectangular sections) together to make a floating bridge. “You can get hurt,” he warns. “Do not get an arm or a leg caught between the bays. It will pinch.” I look at the huge bays and the murky water. It will amputate a limb and you will drown is more like it. Real soldiers can do this in eight minutes. With a lot of help and instruction, our group manages to position the bays — I get to drive the boat — and lash them together with a complicated series of bolts and pinions. It takes us forty-five minutes. Thankfully, no one drowns, although we are soaked to the bone. “Isn’t this fun?” yells Sergeant First Class Jerry Osborne. Yes, sir. Just like Lake of the Ozarks, only I’m freezing, and there is no beer.

1030

Next step, is Chemical Defense Training. We are bused to a secluded compound fortified with high wire fences. Large signs proclaim: “The Use of Deadly Force IS Authorized.” We are told to hand over all contraband food, cosmetics, tobacco, and weapons. I take a look at the sign and, reluctantly, surrender my lip gloss. Sergeant First Class Mike Elmer and Staff Sergeant Rebecca Carey escort us into the building. They will accompany us every step of the way during our time in this area. It’s fun and games for us, but it is clear that security is no laughing matter to them. With the recent threats of chemical terrorism, I’m relieved that the army, at least, takes this seriously.

We are sitting in a conference room in the only indoor facility in the country that uses real toxic chemicals for training. Sergeant Elmer goes over the steps taken to ensure that no hazardous chemicals are released into the environment. The structure is designed to maintain negative air pressure. “Our building sucks,” he jokes. “And has gasket doors and is sealed by layers of concrete with an impermeable layer sandwiched between them.” While we are being assured of our safety, several large booms shake the ceiling. When it is explained that the explosions are just the result of engineers blowing holes in roads, I crawl out from under my desk.

“We’ve Got the Nerve” is the motto of the Chemical Defense Training Unit. The most common danger with this sort of training is dehydration due to overheating in the protective suits. Trainees are checked for respiratory conditions and for odor sensitivity. Why use real chemicals when they are so deadly? Sergeant Elmer explains, “In the field, soldiers must have the confidence that comes from being tested under actual conditions. It gives them credibility with their commanders and with other soldiers. The more you sweat in training, the less you bleed in war.” I’m sweating, I’m sweating.

1200

We didn’t have to use real chemicals. Whew. We did, however, get to dress up in the little chemical suits. And I thought it took me a long time to get ready for work! First, you have to take off everything. Everything. By Army regulation, when any item has been exposed to chemical agents, it must be incinerated at one thousand degrees for fifteen minutes. What’s left after that is safe. Extra crispy, too.

The training outfit is all army, even the lingerie. Victoria’s Secret it ain’t. From the bottom: ugly underwear, something that looks like long johns, socks, pants, jacket, gloves, tennis shoes, moon boots. Sergeant Carey has to help me tie my boots. I should be embarrassed, but I’m just happy to have dry socks. After a brief session on how to identify nerve gas, something really scary happens. Lunch arrives.

They are called MREs. Meals Ready to Eat. In my opinion, that’s pretty arbitrary. Mush Ready to Explode, maybe? There’s a stale candy bar. Peanut butter, with broken crackers. A silver pouch of something orange. “It says it’s tortellini,” whispers the reporter next to me. I have had tortellini. I know tortellini. This, sir, is no tortellini. Napoleon said, “An army travels on its stomach.” My stomach wants Taco Bell. I swallow the peanut butter and do not regret that I have but one MRE to eat for my country.

1300

Grenade training. Now, this is a skill that could come in handy. Noisy neighbors? KaBOOM! Sergeant First Class Kevin Robinson gives us in-depth training on the types of grenades — ours are dummy M-80s, packed with blasting caps — and the proper techniques for throwing. Twist the top. Pull the pin. Duck. NO! Twist the top. Pull the pin. Throw the grenade. Then duck. It’s out to the training field, where, mercifully, it has stopped raining for a moment.

1400

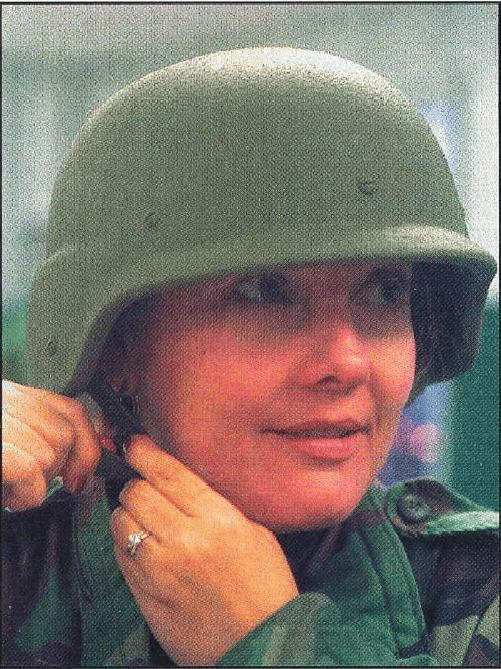

Okay, okay. I’ve heard it for an hour. How shall I put this in military terms? The Rams’ Kurt Warner has no competition from me. In short, I throw like a girl. I do, however, drive like an ace. Next on the agenda: how to operate a High Mobility Multipurpose Wheeled Vehicle. Humvee to you civilians. Sergeant First Class Carl Allison passes out Kevlar helmets and lets us at ’em.

No vanity mirror. You’d think the defense department budget could be stretched to cover the essentials, wouldn’t you? Other than that, it’s a sweet green driving machine. Weighing in at eighty-two hundred pounds, the Humvee is eighteen feet in length and seventy-three inches tall, which gives it a twelve-inch height advantage over me. Does it have a 320-mile range road trip, anyone? — and is just the thing for clearing out rush hour.

I move the seat up. And up. And up. Finally, I can reach the pedals. I start with a slalom course, weaving the hummer in and out of orange construction cones. Whoops. Ouch. Good thing they’re plastic. My passengers look pale as I head to the off-road section. Up on two wheels to drive over a huge rock at a very sharp angle. We wobble but we don’t fall down! Then bumpety- bump-bump-bump — a bone-jarring obstacle course over large logs. Speed bumps would be no problem in this baby. Sand pit! Stuck? Not us! The piece de resistance is a huge water pit with a forty-five-degree incline on both sides. A little wet, but no sweat. This is too much fun. Maybe if I mortgage the house and trade in the Ford? I finish up the course, victorious, and then completely ruin my warrior credentials by being unable to open my own door. Sigh.

1500

It’s raining again – oh happy day – and we are on the bayonet training course screaming “Kill! Kill!” A soldier in green makeup shows us how to stab an old tire with a rifle. “Camouflage,” he snarls. “Not makeup. It’s camouflage.” Whatever. Blood makes the grass grow. So does rain. Soon it is raining so hard that even the drill instructors take pity on us, and we move on to our final destination: Stem Village.

1545

Named in memory of Brigadier General David H. Stem, the village is a tiny fake town complete with its own bar. It’s the latest thing in training simulators. Even the FBI and CIA send agents here. We drip dry while going through “shoot, don’t shoot” scenarios with nine-millimeter handguns that have been modified with lasers. It’s like a life-sized live-action video game. Responses and judgments are timed and evaluated under a number of stressful situations: bank robberies, domestic disturbances, hostage situations, and such.

My turn, oh goody. It takes me twenty-three-hundredths of a second in simulation to fatally wound an unarmed man who was running away from me at the time. “Now I know why he was running,” I hear someone mumble. Watch it, soldier. I’ve got a gun. Sergeant First Class Marvin Applegate, the trainer, suggests that perhaps I might slow my reaction times. “Ummm, you don’t have to kill everyone, he says gently. Oh, all right. I learn a little patience and make fairly reasonable decisions after that.

1630

Still, in Stem Village, I move on to the grenade launcher, the last training of the day. I believe it was General Sherman who said, “War is hell.” It’s hell on a manicure, too; I’ve broken every nail on both hands today. Adding insult to injury, I cannot quite reach the sighting mechanism of the launcher and am forced to stand on a box. Someone who obviously didn’t see me with the nine-millimeter snickers. I narrow my eyes and concentrate on blowing up enemy tanks and helicopters. Sergeant First Class Dan Downs has to assist me a few times before I get the hang of the firing mechanism. “You have short thumbs,” he offers helpfully.

Let’s just say that it’s probably a good thing I’m not actually defending my country. My final score with the grenade launcher is Enemy: 43, Beetle Barnes: 2.

1730

The media day ends with a brief chow in the mess hall. Or a mess in the chow hall. I forget. In comparison to the MREs, this meal is a feast. Colonel Davis, Major Crotts, and Media Relations Officer Mike Warren are on hand to offer us congratulations and certificates of completion. In addition to a fun day of playing with cool toys, they’ve given us a real insight into the workings of Fort Wood. I, for one, am amazed by the quality of the instructors who guided us through our day. No one got hurt, and we learned a lot in a very short time. Just like basic training, I guess. Only we get to leave.

2300

Home at last. I’ve slipped out of my wet camouflage and into a dry martini, a civilian again. Drifting off, I remember the class that graduated earlier today. My military experience is over. For 235 young recruits, service to the rest of us is just beginning. Thanks, soldiers. Sleep well.

Related Posts

Missouri Military Comfort Dogs inspires Worldwide Effort

We introduced you to some civilian comfort dogs previously. Now, meet their military counterparts. Missouri’s USO Comfort Dog Program has inspired nationwide attention.

Bailey & Watkins Traffic in Rawhide & Java

Ryan and Tiffany Watkins of Bailey & Watkins say that every unique piece they create is inspired by a memory, family heirloom, or a story.