On a rainy afternoon, I drive up a country road toward the city of Fayette in Howard County, home to historic Central Methodist University, founded in 1854. I am looking forward to seeing some world-class artwork at the Ashby-Hodge Gallery of American Art on the CMU campus, a hidden treasure just a few miles north of I-70.

I arrive on the campus between semesters, so most of the students have left for the summer. As I stroll through the park-like grounds, I spy the bright colors and intriguing forms of the Ashby-Hodge sculpture garden in front of Classic Hall. I know I am in the right place.

I am greeted by the gallery’s curator, Denise Haskamp, together with one of the Ashby-Hodge founders, Dr. Joseph “Joe” Geist, who currently serves as the collection’s registrar. Both are excited to show me the gallery, including recent new acquisitions donated by CMU graduates. Before we begin, I ask about the most recent sculptural acquisition, Inspiration, a white steel structure that stands eight feet high in front of the building. Joe says this sculpture is by Kansas City artist Rita Blitt, and it was purchased with funds collected in honor of the co-founder of the Ashby-Hodge, Thomas “Tom” Yancey, who passed away in 2019.

The three-dimensional white steel structure is made up of four amorphous shapes that resemble giant steel rubber bands. These forms seem to defy gravity as they undulate skyward, and the sculpture seems a fitting monument to Tom and the unlikely success of the Ashby-Hodge. Tom and Joe were professors at CMU in 1993 when they founded the gallery with a gift of more than one hundred artworks, mostly examples of American Regionalism, donated by CMU alumnus Dr. Lawrence Ashby and his wife Loretta. The gallery was named for the Ashbys and for CMU graduates Robert and Anna Mae Hodge, who were dedicated supporters of the gallery’s mission to provide CMU and the general public with access to important examples of original art. The Hodges provided financial support for the gallery and helped raise additional funds from fellow alumni.

Throughout the following decades the collection grew exponentially, and today encompasses more than one thousand artworks.

As I enter the gallery’s foyer, paintings and small sculptures surround me on all sides. These are works from the permanent collection that rotate through the public spaces outside the dedicated galleries. Joe points out a fabulous mask in a nearby corridor designed by Michael Curry, renowned theater director and artist, who is especially well known as the designer of the masks and puppets in the Broadway production of The Lion King.

I approach the glass doors of the gallery proper and am greeted by a fabulous example of bronze sculpture by one of the most celebrated artists of the American West, Frederick Remington. Mountain Man depicts a fur trapper or trader on horseback, and at the gallery’s entrance, he can be seen as representing the early Americans (many based in the modern state of Missouri) who fueled the economy of the unorganized Missouri Territory in the early nineteenth century.

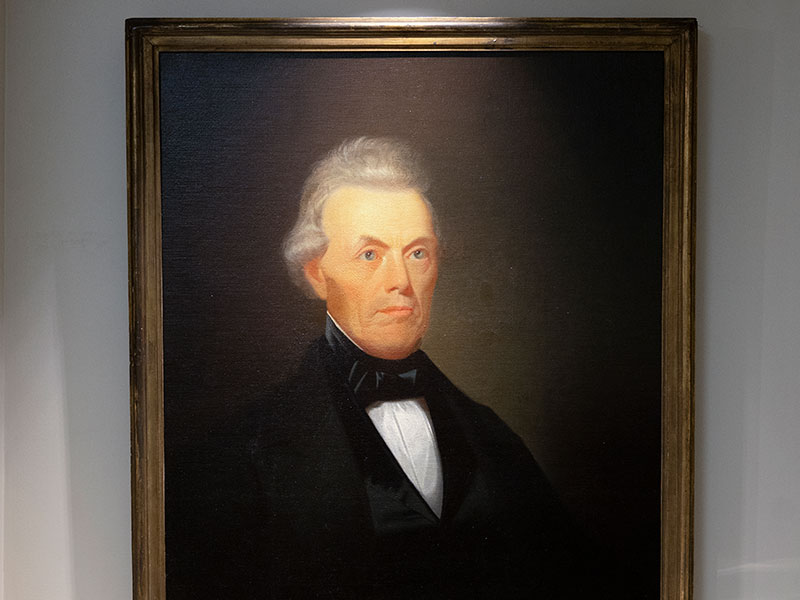

Once inside the gallery, my eye is immediately drawn to a new acquisition: a portrait by the famed nineteenth-century Missouri artist George Caleb Bingham. The painting, dating to about 1845, represents Judge John Ferguson Ryland. It is an excellent example of Bingham’s portraiture, displaying the artist’s skill at capturing skin tones using chromatic oil glazes. The variated olive tones of the background also contrast with the judge’s ruddy complexion to make the colors seem even more vivid. This Bingham is only the first of many exciting surprises I will encounter in the gallery today.

Currently, an exhibition of recent donations from the collection of Central Methodist alumni Bill and Martha Holman line the gallery walls. These works reflect the broadening collecting mission of the Ashby-Hodge, which was founded as a gallery of American art. In recent years, the Ashby-Hodge has offered works by non-American artists, and the organization’s leaders felt they needed to take advantage of the opportunity to provide their patrons with access to these remarkable works of art. The Holman donation, for example, includes a number of works by nineteenth- and early twentieth-century European masters.

Joe draws my attention to a particularly important new acquisition from the Holmans, a delicate dry point created by the celebrated French impressionist Auguste Renoir in 1892. The print represents another famed impressionist, Berthe Morisot, and Manet suggests subtle changes in Berthe’s expression and pose with overlapping parallel lines and broken contours. This etching is not a “portrait” in the traditional sense, but rather and Renoir suggests subtle changes in Berthe’s expression and pose with overlapping parallel lines and broken contours. This etching is not a “portrait” in the traditional sense, but rather a study in gesture and movement characteristic of the impressionist style. With this acquisition, visitors to the Ashby-Hodge gallery can see something few would expect to find in a small-town Missouri art gallery—an original example of impressionism by one of the movement’s founders.

The Holmans collected widely in Paris in the 1950s and 1960s, and their acquisitions include surprising works by some of the most famous artists of the twentieth century. I marvel at etchings and lithographs by Henri Matisse, Joan Miro, Jean Cocteau, and Alexander Calder, but I am also intrigued by works by less well-known artists, such as the color intaglios of Vietnamese-born Lebadang Hoi and the mixed-media compositions of Ivory Coast artist Georges-Ebrin Adringa.

After exploring the artworks on display, Denise and Joe invite me to peek into the onsite storage room. Here I have the privilege of seeing some of the amazing works in the gallery’s permanent collection. I am thrilled to view several beautiful paintings by Swedish-born artist Birger Sandzen, sometimes called “the American Van Gogh,” who spent most of his life in Lindsborg, Kansas. Sandzens are hard to come by, and the beautiful examples at the Ashby-Hodge really showcase the bright vivid color, thick impasto, and broad gestural brushstrokes that typify the artist’s style. The storeroom is filled with compositions by some of America’s best-known artists. I spy drawings by Thomas Hart Benton and multiple artworks by Oklahoma artist Charles Banks Wilson. Highly collectable examples of the twentieth-century work of Joe Jones, Elisabeth Catlett, and Romare Bearden hang in the racks, together with additional nineteenth-century paintings by George Caleb Bingham, Cornelia Kuemmel, and Bingham’s student from Howard County, William Morrison Hughes. Denise and Joe remind me there are many more artworks stored offsite, and I realize that this is just a small portion of one of fastest growing art galleries in the state of Missouri.

After my tour of the Ashby-Hodge, I can’t resist an offer to stop at the campus’s newest museum in nearby T. Berry Smith Hall, the Central History Museum. This collection contains, among other things, historical objects acquired by CMU more than one hundred years ago as part of the Stephens Museum. In 2018, the Stephens Museum was reorganized so the historical collections were separated from the scientific collections and put under the curation of Dr. Robert Wiegers, CMU professor of history. As I enter the rooms of this new museum, I am greeted by Jennifer Parsons, who gives me a brief tour of the collection. I am fascinated by the quality of the objects, from Civil War artifacts owned by Union soldier Jordan Coller to a working early twentieth-century Edison phonograph. Yet as a student of art and history, I am drawn to the collection’s two best-known objects: the gravemarkers of frontiersman Daniel Boone and his wife Rebecca. The inscriptions on both stones spell the name Boone as “Boon” with a backward “n.” The markers were salvaged by family members after the Boones were exhumed in 1845 from their resting place in Marthasville and reburied in Frankfurt, Kentucky. Only the footstone survives from Daniel’s 1820 grave site, but Rebecca Boone’s headstone (ca. 1813) provides the museum with an excellent example of an anthropomorphic grave marker in which the form of the stone is cut to resemble the head and shoulders of a human figure.

These treasures of CMU would surprise many Missourians, and more people should be aware of Fayette’s rich resources. As I wave goodbye to Joe, Denise, and Jennifer, I know it won’t be long before I will be back.

Photos // Joseph Waner, Ashby-Hodge Gallery of American Art

Related Posts

Revitalizing Missouri Downtowns

Here’s how Missourians are working together to revitalize downtowns across the state.

What to Expect When You’re Expecting an Earthquake

An illustrated guide to the end times