This story originally appeared in the May 2021 issue of Missouri Life magazine.

When we think of feuds, the image that often comes to mind is of two multi-generational families, blazing away at each other over some ancient—and largely forgotten—offense. This is indeed one iteration. However, according to the Cambridge English Dictionary, the definition of a feud is considerably wider, covering “an argument that has existed for a long time between two people or groups, causing a lot of anger or violence.” There are, in fact, no numerical restrictions; any number can join in.

Missouri has hosted a handful of feuds in the past. Some had their roots in the Civil War, at a time when border-state loyalties were deeply and bitterly divided. Others, such as the more recent Thompson-Crismon affair, were brief in duration, although still with loss of life. Looking back, each one of these curiosities contributed to Missouri’s violent, colorful past, and each helps us contextualize the lives of otherwise average Missourians in that past.

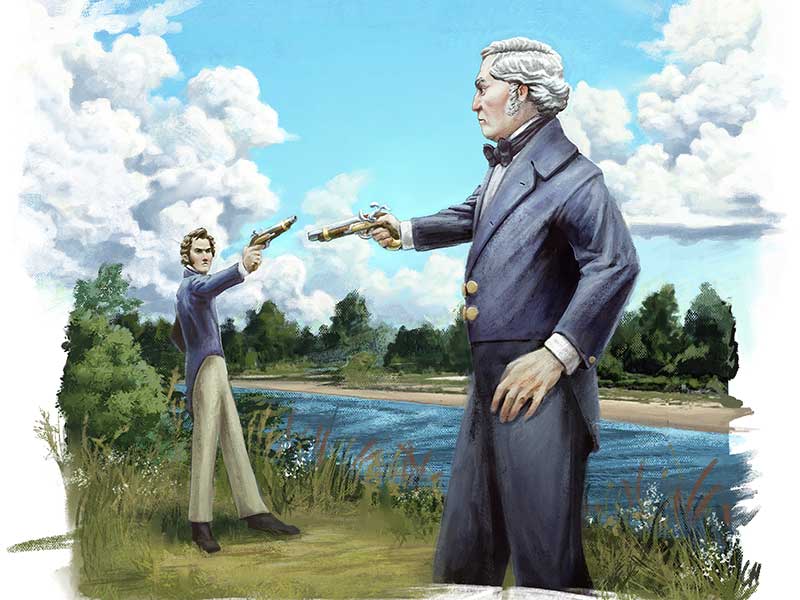

Benton vs Lucas

Duel on Bloody Island

Thomas Hart Benton was a US senator from Missouri in the first half of the nineteenth century, and—as one chronicler put it—an acknowledged “architect and champion of westward expansion.” He was also bombastic and intolerant, ever ready to defend both his opinions and his honor at the muzzle of a gun. Benton’s affinity for settling disputes with dueling pistols began when he was a sixteen-year-old student and challenged a classmate to a duel. Although nothing came of the incident, it established a pattern that Benton would follow well into his maturity.

In this time and place, it was not unheard of for men who saw no other resolution to personal offenses to resolve them on the field of honor. Benton, however, made a routine practice of it. One of his early opponents was the equally cantankerous future president, Andrew Jackson. Fortuitously, both left the field wounded but otherwise intact, and Benton went on to become Jackson’s close friend and strongest supporter.

One of Benton’s most publicized conflicts involved a former friend, Charles Lucas, the young US attorney for Missouri Territory. In 1815, both men were living in St. Louis. Benton took umbrage at something Lucas said and demanded satisfaction. Lucas refused the challenge, and the enmity between the two deepened into what became an ongoing war of words.

At the election polls two years later, Lucas publicly charged that Benton had not paid his property tax on two slaves and therefore should not be allowed to vote. Benton responded, “I do not propose to answer charges made by any puppy who may happen to run across my path.” Now it was Lucas’s turn to issue the challenge, which Benton was only too ready to accept.

The duel was set for the morning of August 17, 1857, on a Mississippi River sandbar, appropriately named Bloody Island. Lying between Missouri and Illinois, it had long been the site of duels, since it fell within the legal jurisdiction of neither state, and duels were outlawed in both.

The first exchange was fired from a distance of thirty feet. Both men were hit, Benton in the knee and Lucas in the throat. The affair was over for the moment, since both men required time to mend.

Sufficiently healed, the two met again on September 27. Lucas had purportedly complained that the distance in the first duel was too great, and gave Benton, who was the better shot, an unfair advantage. Therefore, with Benton’s acquiescence, they now stood a mere ten feet apart. At the order to fire, Benton felled his opponent with a fatal wound to the chest. Historians differ on the nature of Lucas’s last words: he either forgave Benton or swore he never would.

The following news item appeared in the November 5, 1817, edition of the Columbian Centinel:

“On Saturday last Charles Lucas, Esq. a lawyer, was honorably murdered … by Col. Benton, another lawyer. The quarrel originated in an electioneering canvas. The parties had met before, and Lucas had been wounded. On his recovery, they met again, and Lucas was shot through the breast.”

Three years later, Benton was elected to the US Congress as one of the first two senators from the newly minted state of Missouri. It was a position he would hold for the next thirty years, followed by a brief term in the House of Representatives. His reputation as a fighting man followed him. On one occasion, a fellow senator reportedly accused him in open session of being quarrelsome, to which Benton replied, “I never quarrel, sir, but I do fight, sir. And when I fight, sir, a funeral follows, sir!”

Meadows vs Bilyeu

The Feud Over a Fence

Feuds often started over the most seemingly inconsequential of issues. According to oral tradition, the decades-long bloody rift between the Hatfields and McCoys of West Virginia and Kentucky started over a pig, which might or might not have been stolen. The murderous conflict between Missouri’s Meadows and Bilyeu clans—while shorter in duration and considerably less sanguinary—began over the maintenance of a fence.

Feuds often started over the most seemingly inconsequential of issues. According to oral tradition, the decades-long bloody rift between the Hatfields and McCoys of West Virginia and Kentucky started over a pig, which might or might not have been stolen. The murderous conflict between Missouri’s Meadows and Bilyeu clans—while shorter in duration and considerably less sanguinary—began over the maintenance of a fence.

Both families were early settlers of Missouri and could trace their ancestors’ presence in America to the years before the Revolution. In the decades following the Civil War, the Taney County family farms of Steve Bilyeu and John S. “Bud” Meadows adjoined one another. There had been marriages between the families—Bud himself had wed a Bilyeu—and relations had always been cordial. Then Bud Meadows suggested that he and Steve Bilyeu go partners in the construction and maintenance of a rail fence to mark the property line between the two. According to Bud’s later statement, “I was to furnish the rails and Steve was to stake and rider it.” Bud was describing a stake-and-rider fence, common for the era, where wooden rails or “riders” helped enclose the fence.

Apparently, Steve Bilyeu failed to keep his part of the agreement, and by 1897, the fence had fallen into disrepair. “I went to Steve and told him his part was in bad condition and asked him to fix it,” according to Meadows, “but he paid no attention to the matter. Several months later, I again called his attention to the condition of the fence, and he spoke very short to me.”

Tensions between the two families mounted. On one occasion, Steve Bilyeu’s twenty-six-year-old son Pete held a pistol on Bud Meadows and forced him to crawl in public. One observer warned Pete, “That man will kill you for what you made him do. I saw it in his eyes.” It was a warning young Bilyeu would have done well to heed.

Bud Meadows consulted a lawyer, who advised him to serve notice on Steve Bilyeu “that I would hereafter keep up my half of the fence and would remove my rails from the half I was not to keep up.” On November 28, 1898, after getting his father-in-law and brother-in-law—both of whom were Bilyeus—as well as his brother Bob and a friend to assist him, Bud began to remove rails from the fence.

At this juncture, Steve Bilyeu and his two sons, Pete and sixteen-year-old Jimmy, approached carrying guns. Bud Meadows immediately walked to his house and returned carrying his Winchester, his in-laws’ pistols, and his brother’s shotgun. An argument broke out between the two parties, which soon appeared to be resolved. However, as Meadows tells it, he was walking away when someone shouted a warning. He turned in time to see Steve Bilyeu aiming his shotgun at him. Bilyeu fired and missed, whereupon Bud Meadows returned fire, killing his opponent.

Pete Bilyeu and Bob Meadows exchanged shots, missing each other, and as Pete was taking more careful aim, Bud Meadows’s Winchester fired again, and Pete fell dead near his father. Meanwhile, Steve Bilyeu’s grief-stricken widow charged at Bud, slashing his back several times with a butcher knife. Young Jimmy Bilyeu now took aim at Bud Meadows, but the newly widowed Mrs. Bilyeu stood in the way. “He called to his mother to get away,” recalled Bud, “and I realized I would get shot unless I acted quickly. By this time, Mrs. Bilyeu was at my throat, and I threw the Winchester down over her shoulder and aiming at Jim, who was only six feet distant, fired. The aim was true and he dropped dead.”

Within minutes, three men lay dead, felled by Bud Meadows’s deadly rifle. “I am sorry the affair had to occur,” stated Bud, “but Steve Bilyeu and Pete got what they deserved. I regret that I had to kill Jim, who was a good sort of boy—but it could not be helped.”

The Meadows party surrendered themselves to the local sheriff, who jailed all five. Naturally, the Bilyeu family told an entirely different story, blaming Bud Meadows for firing the first shot, killing Steve Bilyeu. Both accounts appeared in the local newspaper, and a lynch mob—possibly influenced by Mrs. Bilyeu’s grief over the loss of her husband and two sons—soon formed. However, the mob was discouraged by the fact that the sheriff had allowed the prisoners to keep their weapons.

Two years of trials and appeals followed, after which all five defendants walked free. Bud Meadows moved to another farm and lived to the age of seventy-eight, reportedly carrying his Winchester wherever he went. According to a regional chronicler, when a neighbor complained to Bud of having been abused by some Bilyeu youths, Bud advised that the only way to handle the Bilyeus was to kill a few of them.

Alsup vs Fleetwood

The Feud That Wouldn’t Die

The story of this seemingly endless interfamilial war unfolded in Ozark (then, Douglas) County. It began decades before the Civil War, and the final gun wasn’t silenced until more than a century later. In its course, the feud reportedly claimed hundreds of lives, and at one juncture, was played out in a full-scale battle.

The story of this seemingly endless interfamilial war unfolded in Ozark (then, Douglas) County. It began decades before the Civil War, and the final gun wasn’t silenced until more than a century later. In its course, the feud reportedly claimed hundreds of lives, and at one juncture, was played out in a full-scale battle.

The Alsup clan—twelve families of them—came to Missouri Territory from East Tennessee in the early 1800s and settled along Bryant Creek. For their part, the Fleetwoods moved from Kentucky in equal numbers and built their homes on Fox Creek. According to oral tradition and a 1915 regional history by native Missouri chronicler am Haswell, the trouble between the two families began in 1820. A Fleetwood youth, walking his girlfriend or fiancée home from church, was apparently set upon by a group of Alsup boys, who beat young Fleetwood mercilessly for no reason beyond what one old-time chronicler refers to as “deviltry.” When an elder Fleetwood attempted to achieve some form of settlement, an Alsup shot him dead. So goes the early account.

From that moment, it was, as the old saying went, “war to the knife and the knife to the hilt.” For the next four decades, each of the two clans took every opportunity to thin the ranks of the other. In this protracted conflict the death toll in the decades leading up to the Civil War purportedly stood at around two hundred.

Four decades later, a neutral party suggested that the two families find closure in open battle. Haswell states, “By mutual agreement, the men of the two clans, now including many of the inhabitants of the region who were not related to either of the original sides, met on a day in October, 1860, to fight out their quarrel to the death, with the tacit understanding that the losers would leave the county to the undisturbed possession of the victors. The chosen battleground was a level plateau between Bryant Fork and Fox Creek.”

According to Haswell, these seasoned mountaineers fought for an entire day, “in the fashion which their forefathers had learned from the Indians, using the trees as shelters, slipping around for a shot at their foes from the rear. As the day drew to a close, a score of men lay dead and as many more wounded.”

By day’s end, several disgusted nonpartisans intervened and put a stop to the battle, declaring it a draw. Each side claimed victory; however, and the feud continued. Finally, neutral locals appealed to the law, and a circuit judge sent the matter to a grand jury, which reportedly indicted some fifty men from each side for murder.

However, before their cases could be heard, the Civil War commenced, and the would-be defendants went off to serve their respective causes, with the Fleetwoods serving the South, and the Alsups joining the Union cause. The end of the war failed to quiet the hostility between the two clans, until the Alsups, through attrition, gained the upper hand. They ruled the county for years to come, controlling elections and maintaining order by whatever means they saw fit to employ.

Then in 1879, a governor’s posse carrying a murder warrant ended the family’s regime by shooting the powerful clan leader Shelt Alsup to death. It seemed that the feud and its turbulent aftermath were finally part of the region’s past. The June 5, 1899, issue of the Springfield (MO) Leader and Press declared, “The famous Douglas County Alsup feud, the fiercest factional war ever fought in the Ozark mountains, is now only a memory. Most of the old leaders on either side of the bloody strife are dead, and the lapse of years has softened the spirit of vengeance in the hearts of their descendants.”

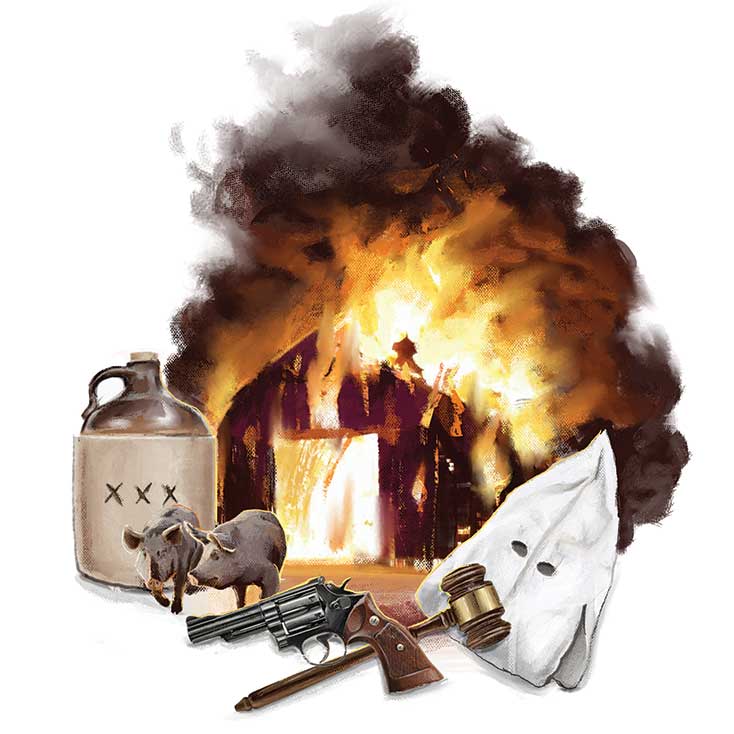

As events would reveal, however, the ill feelings between the two families lived on. The March 20, 1932, issue of the Mansfield, Ohio News reported, “Old Ozark Feud Flares Anew In Ambush Murder.” It told of an Alsup relative who shot and killed a Fleetwood descendant in Douglas County, “in the apparent renewal of a grudge fight which has smoldered for the last fifty years.” The reason for the murder is muddled, somehow involving a barn burning and a charge of moonshining. Whatever the cause, its roots lay in the senseless beating of a youth more than a century before.

Thompson vs Crismon

Putting the Roar in the Roaring ’20s

Not all Missouri feuds had their roots in the 1800s. One in particular, the feud between the Thompson and Crismon clans of Miller County, began in 1922 and ran its course over the next few years, winding down in early 1925.

Not all Missouri feuds had their roots in the 1800s. One in particular, the feud between the Thompson and Crismon clans of Miller County, began in 1922 and ran its course over the next few years, winding down in early 1925.

Reading a series of articles in the 1924–1925 issues of the Miller County Autogram (the self-proclaimed “Official Newspaper of Miller County”), one gets the sense that the members of two neighboring families, for unspecified reasons, suddenly commenced shooting at one another. “The Crismon and Thompson families,” the paper vaguely reports, “have been at outs for some time following differences over school and Sunday school matters, and possibly other things.”

There were indeed “other things” at play that went beyond simple interfamily dissension, which ultimately resulted in mayhem and violent death. According to chronicler Victoria Pope Hubbell, one of whose primary sources was a living member of the Thompson clan, one of these “other things” was the local chapter of the Ku Klux Klan.

Both families were natives of Wilcox Bend, so named for a dogleg in the Osage River. Since the early 1800s, people had been migrating to this location to take advantage of the rich river bottom soil. As communities such as Bagnell and Eldon established themselves in the region, so, too, did the inevitable saloons, brothels, and intolerance. As early as 1915, the Ku Klux Klan made its presence known in the area. “Suddenly,” writes Hubbell, “people who had been working and living together for a century began noticing differences in their neighbors.”

Traditionally, the Klan had targeted Jews, Catholics, and African Americans. However, in the absence of any of these groups in Wilcox Bend, residents whom the Klan determined to be of questionable moral character—moonshiners, gamblers, purportedly loose women, and those who refused to join their ranks—made for convenient scapegoats and targets. Whippings and the killing of valuable livestock became the order of the day, carried out in the dark of night by robed and hooded locals.

One of the earlier families to settle at Wilcox Bend was the Thompsons, and by 1922, John Grant Thompson was the patriarch. A farmer as well as the local blacksmith, Grant had a large family, having sired seven children by his first wife, and—after she died—six more by his second.

The Thompsons’ nearest neighbors were the newly arrived Crismons. Fred, the head of the family, soon became an enthusiastic Klan member, as did at least one of his sons. For his part, Grant Thompson avoided any involvement with the so-called “Klavern,” thereby earning their enmity. According to Grant’s son Hadley, when he was interviewed in his mid-eighties, this was the initial cause of the feud between the two families. Exacerbating the situation, Grant Thompson was a moonshiner and a drinking man, whereas Fred Crismon was both a teetotaler and a justice of the peace, committed to enforcing the recently instituted Prohibition laws.

Not surprisingly, Fred Crismon’s grandson Leo remembers things differently. He assigns the beginning of the trouble to a court action that Fred, as local justice, decided against the interests of the Thompsons. “From that time,” he recalls, “in passing our house the Thompsons carried guns and kept them pointed at the house. Also threatening and insulting gesticulations were performed by them as they passed.”

Both descendants agree that there had been a business deal involving the purchase of several hogs, which went sour. Each side blamed the other, and the cordial relations that had initially existed between the two families soon grew to resentment and then to hate.

At this point, the Klan took a hand on Fred Crismon’s side, forbidding locals from frequenting Grant Thompson’s blacksmith shop and peremptorily ousting his stepdaughter from her position as the local schoolteacher, replacing her with Fred’s nineteen-year-old son, Francis. Then, on January 3, 1924, for reasons that remain obscure, Fred Crismon and another family member fired on Grant Thompson and one of his sons with shotguns as the Thompsons drove their wagon past the Crismon farm, hitting both seriously, but not fatally. Grant immediately filed charges against Fred, but the trial resulted in a hung jury. According to Hadley Thompson, by this time both the newspaper and the local law were controlled by the Klan.

Members of both families now carried guns in plain sight wherever they went. Shots were occasionally exchanged, and one night, Grant Thompson’s barn mysteriously burned to the ground.

In late November, Grant fired his pistol at Fred Crismon, striking him in the shoulder. He was charged with felonious assault, but before he could be tried, tragedy struck.

On a bitterly cold December 4, Grant Thompson and his eldest son, eighteen-year-old Charley, happened to meet Fred and Francis Crismon at the local Bagnell Ferry, whereupon an argument ensued. According to Charley Thompson, Fred Crismon raised his shotgun and, without provocation, shot Grant Thompson in the head, killing him instantly. In the scuffle that followed, Charley fatally wounded young Francis Crismon. Naturally, the Crismons told a different story, citing Charley Thompson as the first to fire, shooting Francis in the back, whereupon Fred Crismon killed Grant. Whatever the order, two men perished.

When Francis Crismon died, the local paper reported, “an escort of more than seventy members of the Ku Klux Klan, in full regalia, escorted the body to Eldon Cemetery where the regular order of service was conducted by officers of the Jefferson City Clan Realm of Missouri of the Invisible Empire of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan.”

Charley Thompson was charged with Francis’s murder, while Fred Crismon was arraigned for killing Grant Thompson. Meanwhile, the local Klan met and voted to “wipe the Thompson family out.” Heavily armed friends of the family protected the house, however, and no one wearing a robe and hood appeared. Around this time, Fred Crismon relocated his family from “near Bagnell” to Eldon, a move that—had he done so sooner—would have spared two lives.

Charley Thompson was subsequently acquitted “on the grounds of self-defense,” and the charges against Fred Crismon were dismissed, since no witness would identify him as Grant Thompson’s killer. According to Grant’s son, Hadley, “the jury was stocked with KKK who would never convict a Crismon.”

Owing to the efforts of the grand jury, the feud between the two families was resolved in a single court session in late March, 1925. According to the April 3 issue of the Miller County Autogram, “A mutual agreement was reached last week between the Grant Thompson and Fred Crismon families when all agreed to let bygones be bygones and drop their contentions and strife.” The article concludes, “Blessed are the peacemakers.”

When Gunfire Replaces Reason

In retrospect, the feuds of Missouri, homegrown though they were, differed little from other such bitter conflicts. A feud’s beginning was deceptively simple: perhaps an ill-chosen remark or an aggressive act begat physical violence, which in its turn, escalated to a place where peaceful resolution ceased to be an option. People perished, most often by gunfire, in bloody altercations that claimed lives and lasted anywhere from a few years to more than a century. Ultimately, when the dust settled and the last grave was dug, little if anything had been resolved through the course of these incidents. It remained for the newspapermen, historians, and folklorists to pick over the bones, argue the most minute details, and ultimately, relegate the event to its place in the archives of the state or region that spawned it.

One More Feud

Some readers may have noticed the omission of a reasonably famous Missouri feud, that of the Dooley and Harris clans, from this article. The feud raged on through a handful of lethal engagements around the beginning of the twentieth century. Most of the conflict was near Farmington, and the St. Louis Post-Dispatch covered it in detail. The reason it is not examined here is because Missouri Life previously covered the rivalry in our October/November 2014 issue. Those interested in the story can order back issues or read the story online here.

Recommended Reading

For a fascinating, well-written account of a Missouri feud, check out Blood River Rising: The Thompson-Crismon Feud of the 1920s, by Victoria Pope Hubbell (Iris Press, Oak Ridge, TN, 2016).

Illustrations by Spencer Owen

Related Posts

Revitalizing Missouri Downtowns

Here’s how Missourians are working together to revitalize downtowns across the state.

Missouri Plein Artist Billyo O’Donnell Shares His Art

Meet the Missouri plein air artist who translates with paint.