Missouri’s rural beauty is on full display during the drive to the Linn County farm of artist Nora Othic. Situated between Marceline and Brookfield, Nora’s farm is a few miles south of Highway 36. Within view of her studio, a fish-filled pond borders farm fields and dense woodland. According to the artist, fewer songbirds and butterflies have visited over the last few years, so Nora and her husband, John, are allowing much of the land to return to its natural state.

Nora’s father came from Marceline, and though she was born in the state of California in 1954, she spent her childhood on farms in Marceline and nearby Laclede. Born Nora Oldham, she has lived most of her life in north-central Missouri, finding artistic inspiration in the country landscape and its people. She received her bachelor of fine arts from the University of Missouri in 1991, and since then has worked full-time as an artist. Today her work is represented in galleries, museums, and private collections throughout the Midwest and beyond.

Nora calls herself a Neo-Regionalist, in the “art speak” of critics and art historians. Like famed Depression-era Regionalists Thomas Hart Benton and Grant Wood, she paints what she knows, transforming rural landscapes, figures, and animals into environmental archetypes and incarnations of the human condition. She meets me wearing paint-stained denim overalls, her long white hair pulled back in a ponytail. She looks the part of a painter in tune with rural America.

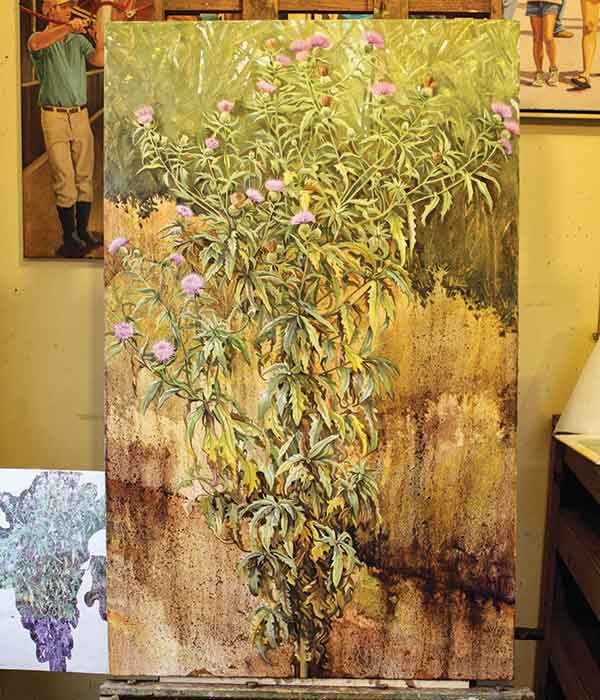

During my visit to the Othic farm, the artist suspended work on her latest large easel painting of a thistle. Having rubbed a thin base layer of yellow-gold oil paint onto her canvas, she is articulating the forms of the thistle with thicker layers of color. Beside the painting-in-process, a photo collage provides a reference image of cut-up photos of a thistle rearranged by Nora to create a pleasing composition.

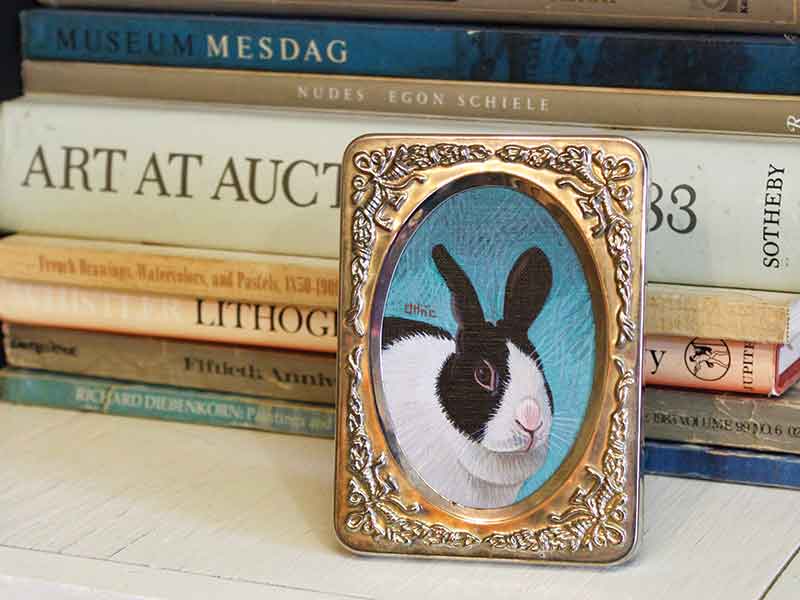

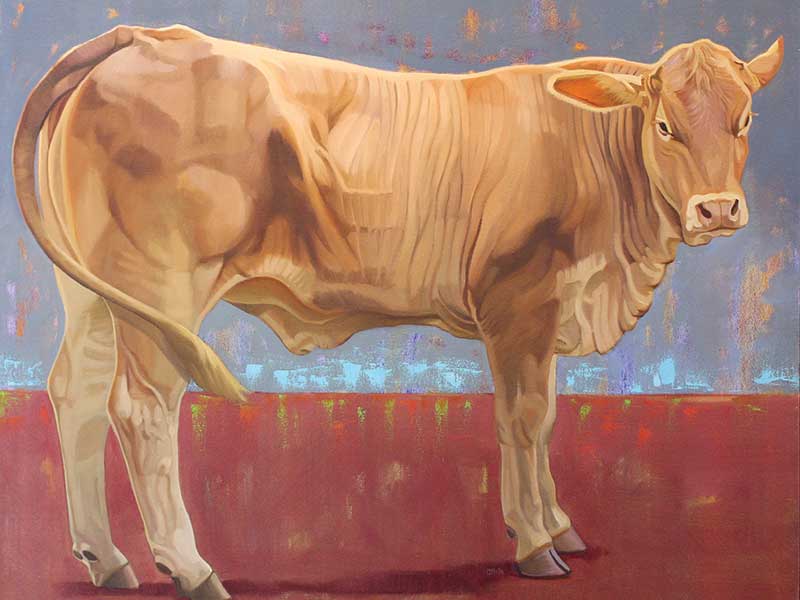

Nora speaks of her desire to understand and explore the nature of plants and animals through art. She admires Ursula K. Le Guin, a science fiction and fantasy writer who wrote about the human longing to comprehend the zoological and botanical “aliens” living among us. A recent painting of a young Brahmousin bull hangs on the studio wall, and the artist describes her youthful fascination with the power and beauty of these formidable farm animals. Many of Nora’s exhibitions feature such intensely observed animal portraits. These paintings and pastels of barnyard creatures vary from large pictures (like the studio bull), to intimate miniatures framed like family photos. A tiny portrait of a domestic rabbit sits on Nora’s studio bookshelf, a fitting foil for the massive bull nearby.

Despite her fascination with nature, Nora’s images of rural people are arguably her most powerful. In her paintings, everyday folks wear T-shirts, tank tops, and jeans. They work in barnyards, relax at barbecues, and brawl in bars. The artist often gives these figural works witty titles that allude to mythic characters or Biblical stories.

For example, The Three Graces at the Barbecue, recently purchased by the Daum Museum of Contemporary Art in Sedalia, pictures a group of four men and three women surrounding a barbecue grill. The three women stand close together with their bodies positioned to reveal varying views of their faces and figures. Those familiar with classical and neoclassical art will connect their poses with images of Aglaia (Beauty), Euphrosyne (Joy), and Thali (Abundance), the “Three Graces” who oversaw the feasts of the ancient gods. With her tongue-in-cheek title, Nora encourages us to see mythic characters embodied in the backyards of our neighbors. She shows us the universal in the vernacular.

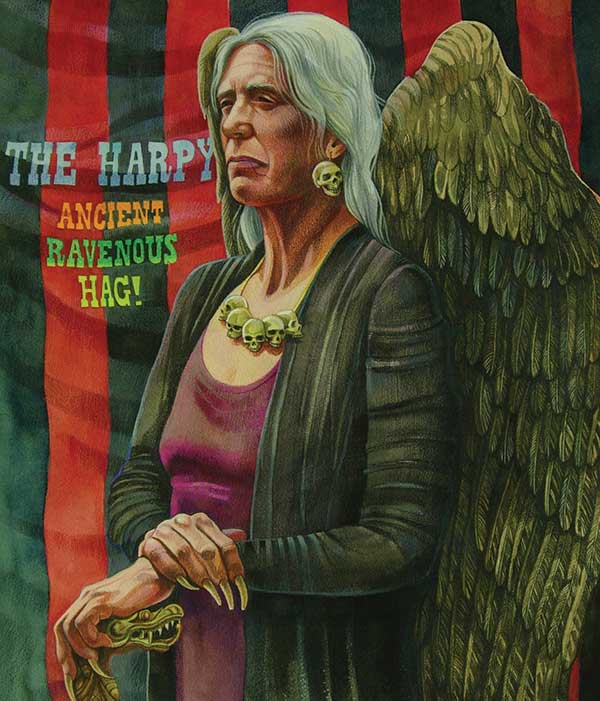

Nora’s latest mythological series featuring modernized beings as carnival sideshow exhibits recently sold out. The series included a self-portrait of the artist as a harpy—the Homeric half-woman, half-raptor creature that embodies divine vengeance and nature’s destructive forces.

Aside from this sardonic self-portrait, the sideshow series includes Medusa, The Minotaur, The Cockatrice, and many other mythical beings. Nora’s personal favorite is The Satyr, which she pictures as a handsome young guitarist with ram’s horns. In Greek and Roman mythology, the satyr is a half-man, half-goat nature spirit whose carnal impulses reflect humanity’s animal nature. Holding a guitar and wearing earrings in his pointy, goat-like ears, Nora’s satyr wears a Lynyrd Skynyrd T-shirt above his furry legs. The imagery suggests that this mythic being would be right at home in the contemporary world of rock and roll music.

I ask Nora what motivates her to create images like these, in which she melds the mythic with the familiar. She tells me that the concepts often begin as gimmicks to give unity to upcoming exhibitions, yet these gimmicks invariably allow her creative juices to flow. Nora is an avid reader. Modern and classic novels, as well as books on mythology and art fill her studio. Whether she is inspired by Homer or science and fantasy writer Ursula K. Le Guin, her wit and powers of observation encourage us to see the profundity in the everyday world of rural Missouri.

Nora’s artwork is in the permanent collections of the Daum Museum of Contemporary Art in Sedalia; the Nerman Museum in Overland Park, Kansas; The State Historical Society of Missouri in Columbia; and the Ashby-Hodge Museum of American Art in Fayette. She is represented by the Sherry Leedy Gallery of Contemporary Art in Kansas City; Sager-Braudis Gallery in Columbia; the Strecker-Nelson-West Gallery in Manhattan, Kansas; and Beauchamp’s (gallery) in Topeka, Kansas.

Photos // Nora Othic

Related Posts

How a Holden Dairy Farm Found its Niche

This dairy farm found sweet success after the owner, Janet Smith, took it over and made some changes and creating new products.

An Old-Time Holiday at Hermann Farm

Celebrate Christmas the German way at Hermann Farm.

Inside a Christmas Tree Farm

The Boonville Christmas Tree Farm has more to offer than a tree to decorate.