It’s been 50 years since sex, drugs, and rock and roll hit Sedalia at the 1974 Ozark Music Festival. Depending on whom you ask, it was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to experience the 70s’ biggest bands or an off-the-rails disaster

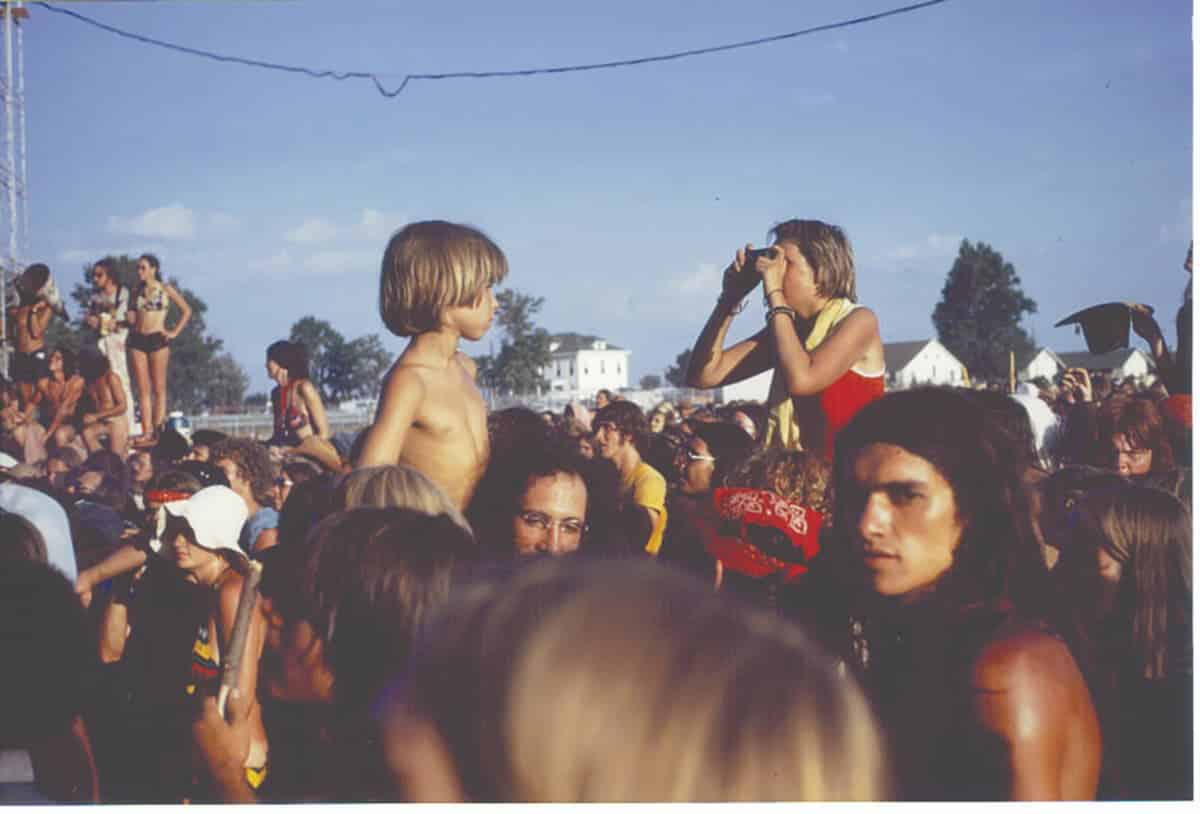

Photo courtesy of Jefferson Lujin

Gone are the days when Sedalia’s main claim to fame was being the trailhead for thousands of irascible, tick-ridden, Texas longhorn cattle. To many Missourians, the most extraordinary event to take place in Sedalia’s history was the Ozark Music Festival that was held 50 years ago in July 1974. The festival followed the iconic Woodstock Music and Art Fair by five years, and it has been touted as both a star-studded, coming-of-age Southern rock festival and an unmitigated disaster that sparked an outraged response from the community and the Missouri State Senate.

In the wake of the event, the senate appointed a special committee to investigate and “determine why it was permitted to happen [and to] propose protective legislation that would prevent such an occurrence from happening again.”

The notoriety of the 1969 Woodstock Music Festival struck a spark among various show promoters. Chris Fritz, a Kansas City resident and enterprising head of the then newly incorporated promotion company Musical Productions Inc., saw Sedalia—which at the time was home to roughly 23,000 residents—as the perfect venue for a rock music festival.

A Half-Baked Plan

In late February 1974, Musical Productions Inc. proposed a three-day music festival to be held in July on the Missouri State Fairgrounds, located just off the main thoroughfare in Sedalia. The proposal was presented to both the secretary and attorney for the Missouri Department of Agriculture. It stated that the festival would consist of approximately 12 bands, playing to an audience of some 50,000, who would be primarily between the ages of 16 and 25. The promoters also assured the two state officials that the festival would only offer “bluegrass and light rock”—a promise they would continue to make until the day the festival began. Longtime KOPN radio host and commentator Kevin Walsh, who has interviewed hundreds of the festival’s attendees, described the situation as “a half-baked plan presented to a board of squares at state.”

Photo courtesy of Jefferson Lujin

According to the subsequent senate report, the promoters agreed to “provide: (a) Traffic Control; (b) Security of Persons & Property; (c) Health and Medical Facilities; (d) Administration; (e) Gate Attendants; (f) Food & Beverage Concessions; (g) Talent Arrangements; and (h) Other Attractions.” They also submitted a bid of $40,000 for the rental use of the fairgrounds. The promoters’ promised services would ultimately prove to be either inadequate or nonexistent.

Significantly, an inclusion in the final contract specified that the state could not legally cancel the festival until the actual three days of the event itself, whereas the promoters were free to cancel at any time. Apparently, none of the four attorneys representing the state had read the entire contract.

Additionally, the agreed-upon rental fee was comparatively low. The senate committee report later stated, “The promoters expressed great surprise that the state had accepted such a low figure,” especially when considering the state fair itself paid Missouri approximately $200,000 annually from the midway and concessions alone. The state also made the unprecedented offer to “undertake the responsibility of removing trash and debris from the premises and improvements … before, during, and after the expiration of the lease herein made.” Post-event cleanup was a task generally assumed by the lessee. It was a concession the state officials would come to regret.

The Promoter’s Hype

So anxious was the secretary to approve the lease that he offered Musical Productions Inc. a liquor license for the event— which the promoters refused, stating that many if not most of the ticket buyers would be below the legal drinking age.

Photo courtesy of Jefferson Lujin

During the course of contract negotiations and up to the time of the festival, officers of Musical Productions Inc. made various representations and statements about the upcoming event that would far underestimate reality. One of the most repeated predictions was the anticipated crowd size. The number of people projected to be in attendance always hovered around 50,000; to this day, it is not known on what formula or set of calculations this remarkably inaccurate figure was based.

When initially asked by the state’s agriculture officials if the festival would be basically just another rock concert, the response was, “No, this [is] an entirely different concept we are working towards. … It’s an entertainment concept. Mid America’s young adults will come together … to experience an exposition geared to their varied interests. Music, arts, and crafts exhibits, amusement rides, and a variety of presentations will make up the festival. In essence, the event will be a cultural experience.”

Other press releases continued to stress the uniqueness and broad appeal of the event. “The festival will showcase various craft demonstrations, including pottery making, ceramics, leather works, glass blowing and jewelry making. There will also be camping, skiing, and other sports.”

A blurb in the Neosho Daily News of May 9, 1974, added, “A midway with 24 major rides will also be part of the festival.”

Clearly, the hordes of young people who would be coming to Sedalia for the three-day rock concert would have little if any interest in glass blowing, pottery making, or skiing, if any kind of skiing could have occurred. It was summertime, and there’s no lake for water skiing on the fairgrounds. It was just the promoters’ hype.

Nonetheless, the hype continued. The promoters put out the word that NFL football legend Bart Starr had been asked to address the crowd. According to the senate committee report, “Mr. Starr expressed grave concern that his name had been used by Musical Productions, Inc. He stated he had never been contacted by the promoters and if he had been contacted he would not have participated in any way.”

Photo courtesy of Jefferson Lujin

The promoters also promised “an abundance of water and restroom facilities and a large number of concessions with a wide variety of food [would] be available throughout the grounds.”

What they failed to consider was the fact that Missouri’s July heat can—and in fact, would—reach a humid 100 degrees. America band member Lee Merton “Dewey” Bunnell later recalled, “We arrived in a helicopter … and it was incredibly hot! Everyone was sweating and sunburned.” Given the size of the crowd that would actually attend the festival and the lack of proper facilities, the shortage of food and drinking water would become intense. In short, the promoters were selling far beyond their ability to fulfill their promises.

Word of the festival had clearly gotten out; although there was no internet, cable, or MTV at the time, news of the event had spread far outside the state through such entities as Rolling Stone magazine, the Wolfman Jack radio programs, head shops, and countless local newspapers, as well as by word of mouth. The promoters had printed some 50,000 tickets, while the arrivals in quiet little Sedalia numbered between 150,000 and 400,000, depending on whom one asks.

Extraordinary Bands

Many were coming to see and hear their favorite bands, and many highly regarded acts appeared. Several bands would go on to have international notoriety. Among others, the list included: Bachman-Turner Overdrive, Aerosmith, Blue Öyster Cult, the Eagles, America, The Marshall Tucker Band, The Nitty Gritty Dirt Band Boz Scaggs, Ted Nugent, David Bromberg, Leo Kottke, The Earl Scruggs Revue, Joe Walsh, Lynyrd Skynyrd, Bob Seger & The Silver Bullet Band, The Charlie Daniels Band, Jefferson Starship, REO Speedwagon, and the homegrown Missouri rock band Triphammer. Bruce Springsteen had been booked, but did not end up performing. He had not become a superstar yet, and no one seems to know for sure why he didn’t perform, whether it was because he was late, the weather was too hot, or he simply changed his mind.

It was an extraordinary lineup. “There seems to be much agreement that the music was excellent. It was just everything else that was a problem,” according to one account.

The crowd was diverse. Triphammer keyboardist and singer Banastre Tarleton recalled his first impressions: “When we started playing, there were only 30 or 40 people listening. Suddenly, we saw a big variety of people coming in—hippies, girls hardly dressed at all, bikers, rednecks, and average looking people—‘squares,’ the kind you’d see working in a shoe store.”

A Chaotic Downtown

Jefferson Lujin, who grew up in Sedalia, has spent the last 15 years speaking with people who attended the festival. He is in the process of completing a full-length film that will consist of archival footage and interviews. Commenting on the impact of the event on the town, he states, “No one had ever done a festival in the middle of town before. Stores boarded up their windows, and there was a general paranoia that the festival goers would burn down the town.”

A number of businesses suspended operation when the fes tival crowd overflowed onto the streets, in some cases making it impossible for employees to get to work. A local farmer filed a complaint that some of the earlier arrivals had wandered onto his farm and slaughtered his livestock. And the supermarket lost dozens of shopping carts to attendees who took them, lit fires beneath them, and used them as cooking grills.

Photo courtesy of Jefferson Lujin

Four days before the festival began, 19 officers entered the fairgrounds with arrest warrants for drug violations. Some of the few hundred fans who had arrived early began throwing cans of corn, stones, and pieces of pavement at the officers, who drew their weapons “to hold the crowd at bay.” It was learned the next day that a promoter had assured the crowd that the police had been ordered to stay outside the fence unless buildings were being burned. Further, no effort would be made to impede the purchase and use of marijuana.

Once the festival began, things started to become undone. In Lujin’s view, “Security was the main downfall. … The stage itself was well managed, but everything else was a disaster.” The promoters had brought in Wells Fargo to handle security, but instead of using a trained, experienced staff, the company adopted a “peer group” plan and brought in juniors and seniors from Central Missouri State University, now the University of Central Missouri, in nearby Warrensburg. In Lujin’s words, “They hired untrained kids, gave them each a T-shirt, and sent them in. No one knew what they were supposed to do. The kids simply joined the crowd.”

At this juncture, local police remained outside the chain link fence that surrounded the event. “Cops watched from outside the fence,” Lujin says, “because they considered it too dangerous to go in.” Before the festival, the promoters had asked Col. Sam Smith of the State Highway Patrol if his agency could act as a paid security force, but he responded that they did not function as a private service, nor did they traditionally interfere with events taking place on the fairgrounds. At a prefestival meeting with the promoters and representatives of Wells Fargo, Col. Smith was unimpressed with Wells Fargo’s plans for security. He predicted, “They’re going to break down your fences,” and he assigned 20 patrolmen to the festival.

Motorcycle Gangs

In addition to the hundreds of motorcyclists who roared into Sedalia, approximately 80 or 90 bikers from such gangs as the Fourth Reich, the Scorpions, the Diablos, and the notorious Hells Angels soon made their presence known. As the festival progressed, and as Col. Smith had accurately predicted, some gang members rolled up the fence and began charging participants a fee for crossing their “territory.” In at least one instance, the situation turned violent when a young man refused to pay.

Then there were the drugs. The senate committee report later concluded, “Every hard drug known to law enforcement … was openly advertised and merchandised.” These included marijuana, LSD, cocaine, TCP, mescaline, amphetamines, and heroin. Some peddlers set up shop in abandoned concession stands. According to Lujin, “One guy with a placard around his neck was selling shots of heroin and carrying his syringes in the bullet loops of a cartridge belt.” There would be as many as 1,000 overdoses, one resulting in the death of a young man.

In addition to drugs, commercial sex was easily available and inexpensive. Two empty school buses and a shack on which someone had spray-painted “Bruno’s Whorehouse” were converted into brothels offering sex, or “a thrill,” for two dollars (about $12 today). Couples were openly having sex, and signs were posted advertising an orgy to be held in the fairgrounds’ sheep pavilion.

Signs that there would be a strong presence of drugs and that security would prove grossly inadequate had been made abundantly clear just two weeks earlier at the Chuck Berry Festival, a much smaller event held in St. Charles County. Undercover agents in attendance later reported that they “had never seen so many drugs at a rock festival before.” According to the senate committee report, the Highway Patrol “forwarded written reports … indicating there was open sale and use of drugs, security was inadequate, and approximately $20,000 in damages had been inflicted by a crowd of 18,000.”

Word from the local Sedalia head shops was that this festival would see even more drug activity with a crowd several times the number of the St. Charles festival. Additionally, there were reports “indicating security personnel working at the Chuck Berry Festival were observed smoking marijuana, holding up fences to let people into the grounds without a ticket, and some took off their security T-shirts and joined the crowd.” It was an accurate preview of what was to come.

The day after the Chuck Berry Festival, a meeting was held with the governor to discuss the fallout from the event. It included Col. Smith of the Highway Patrol and two undercover agents who had been at the festival. With the Ozark Festival still two weeks away, Col. Smith strongly suggested that it be canceled. However, because of the contract clause denying the state the right to cancel the festival until it had begun, the Missouri Attorney General voiced the opinion that “the State would probably not prevail if suit were brought for breach of the lease agreement.” The festival would go on as scheduled.

No Food, Water, or Clothing

From the time the first festivalgoers arrived in Sedalia, the temperature remained around a humid 100 degrees. Many in the audience—both male and female—shed their clothing and walked the festival completely nude, some adorning themselves with body paint. Coed showers became the norm. Kevin Walsh states, “Nudity was the thing. Nobody talks about the drugs; they do, however, talk about the nudity.”

According to the July 17, 2009, issue of Poplar Bluff’s Daily American Republic, state researcher John Hall reported that the widespread nudity was driven as much by a need for relief from the oppressive heat as any act of violence or social commentary. “No one made a production of their nudity, and the heat apparently limited those in the nude to strolling rather than streaking,” he testified. In fact, some people slathered mud on their bodies to counter the heat.

At a prefestival meeting in which the possibility of nudity was discussed, a Wells Fargo representative had stated, “They better run damned fast, or we’ll catch them and eject them.” In fact no one ran, nor was anyone ejected.

In addition to the lack of adequate security, a number of other vital amenities promised by the promoters failed to materialize. Food and water quickly ran out, and the hungry visitors began patronizing a grocery store outside the fairgrounds. In addition to providing drinking water, the owner also allowed them the use of his hose on account of the heat.

Relief of another kind also became a major issue. The number of port-a-potties installed on the grounds was grossly insufficient to accommodate a crowd of that size; a security guard soon reported them “full to the seats.” According to Lujin, “They overflowed immediately, creating a sickening stench. There was crap everywhere.” When the port-a-potties filled, some participants overturned them in frustration, setting some of them afire. Lacking facilities, many attendees merely relieved themselves on the grounds. Soon the field was devoid of grass, and as it began to rain, the fairgrounds were churned into mud and worse.

The promised traffic control was virtually nonexistent, either at the festival or on the roads; the promoters had opened the gate to only one parking lot, despite the Highway Patrol’s pleadings to honor their promise to make more of the lots accessible. The lot soon filled, and abandoned and broken-down cars blocked Highway 65 in both directions for a distance of several miles. Some drivers simply left their cars and slept on the city streets. On July 19, the first actual day of the festival, the governor ordered the National Guard to tow any vehicles blocking public roadways.

One of the more serious shortfalls was in the promise of an adequate medical presence throughout the festival. Here, as elsewhere, the promoters overpromised about both the nature of the festival and the ages of the audience. When physicians expressed concern about heavy drug use, they were assured that most of the fans would be between 24 and 26, “beyond the age of the so-called hard drug users,” and that there would likely only be a “few drug cases.”

Dr. A. J. Campbell, one of the physicians approached by the promoters, later testified, “I think it was misrepresented to us from the start as to the scope we would encounter. In fact, … I was pretty upset about the fact that we were not told the truth from the start; we were misled and told it would be an Ozark folk festival, with bluegrass music and some light rock. That was not the case at all.”

Nonetheless, suspecting that the drug problem would prove greater than described, Dr. Campbell assembled a 43-person staff, whereas the State Fair traditionally used only three. They were aided by the National Guard, as well as volunteers from Columbia, Springfield, and St. Louis. The medical facilities were full throughout the festival, the doctors working 18 to 20 hours a day. The two ambulances provided by the promoters proved insufficient for the number of people needing hospitalization.

The Cleanup Catastrophe

Col. Smith of the State Highway Patrol later claimed to have been misled as well, stating that he had been “told very emphatically … that this would be a bluegrass festival, some country music, we would have an old fiddlers contest, we would have Sunday church services, and we would have a very nice group of people.”

Photo courtesy of Jefferson Lujun

The festival continued for all three of the planned days, but according to Jefferson Lujin, “On the day after the festival, Highway Patrolmen linked arms and drove everybody out.”

Then began the nightmare of the postfestival cleanup. The Sedalia Democrat described the grounds after the event as a “mountain of human waste and dirty syringes.” Lujin states, “Inmates from the Missouri State Penitentiary in Jefferson City were brought in to bring the fairground back to a semblance of normal. They removed the stunning mass of detritus, bulldozed off the topsoil, and put down lime to rejuvenate the grounds.” By the time the fairgrounds had been put back in order, the cleanup cost was nearly $47,000. Overall damages were found to exceed $100,000.

Once the proverbial dust had settled, the state senate assigned its committee to conduct an investigation. After going into specific detail for some 67 pages, the committee report concluded, “The Ozark Music Festival can only be described as a disaster.” It bluntly stated that the contract between the state and the promoters “should not have been executed,” adding, “The advice of the law enforcement sector should have been followed, the attorneys representing the state should have read the contract, and legal action should have been instituted.” The report proposed legislation to ensure that rock festivals could no longer take place in the state, but the legislation never went anywhere.

Chief promoter Chris Fritz reportedly left town immediately after the festival, upon hearing a rumor that a lynch mob was looking for him. Outraged citizens of Sedalia demanded a reckoning. The heads of Musical Productions Inc. were charged with misleading advertising and running a confidence game. However, after months of hearings, all charges were dropped. Meanwhile, Wells Fargo sued Musical Productions Inc. for fraud and nonpayment, while the promoters in turn sued Wells Fargo for inadequately performing their guard duty responsibilities.

A Coming of Age

Whether it is viewed as a coming-of-age experience or an unmitigated disaster, the 1974 Ozark Music Festival remains a ready source of conversation. Greig Thompson, Art Collections Manager at The State Historical Society of Missouri, attended the festival when he was 15. He says, “My parents weren’t pleased, but I was insistent. It was the cultural experience I wanted. There were some real physical hardships; on the other hand, there was some great music being played. We endured [the heat] till the sun went down, then it was magic.”

Deborah Kroh recalls the entire three days she spent at the soundboard with the various musicians and stagehands. “I was 16, and there were a lot of kids my age, from small towns in Arkansas, Oklahoma, Kansas, Missouri. Most of them had not had the opportunity to travel much, if at all, so it was the opportunity of a lifetime to be there. These musicians had been our heroes growing up, and to see and hear so many of them—and at that price—was the big event of our lives.” Tickets cost $15 (about $95 today) for the entire festival.

According to Kevin Walsh, “This festival elevated country rock onto the main stage. For years, when I ran my music store, people would come in regularly, each with their own stories. It was a watershed event. And whenever it’s discussed on the radio, the phones light up!” He adds, “These were kids, 15, 16. It was the first time many of them had gone against their parents. When they got there, they found thousands of kids just like them, from such small towns as Cuba. This was validation. It was the beginning for a lot of kids, their origin story. Music is a great unifier, and it defined their lives for years to come.”

A week after the Ozark Music Festival, Sedalia was once again in the news, this time on a national level. NBC’s Walter Cronkite calmly reported on the first of what would become Sedalia’s annual Scott Joplin Ragtime Festival, a considerably more sedate event than the rock festival that had descended like a shock wave on what the Kansas City Times of July 27 called the “small Missouri town nestled between two grass-kissed hills.” It was, the newspaper declared, a “welcomed change.”

Featured image courtesy of the State Historical Society of Missouri

Article originally published in the July/August issue of Missouri Life.