Here is the story behind a Pearl Harbor Hero who stayed in a home that is now for sale in Fair Grove. For the full listing, click here.

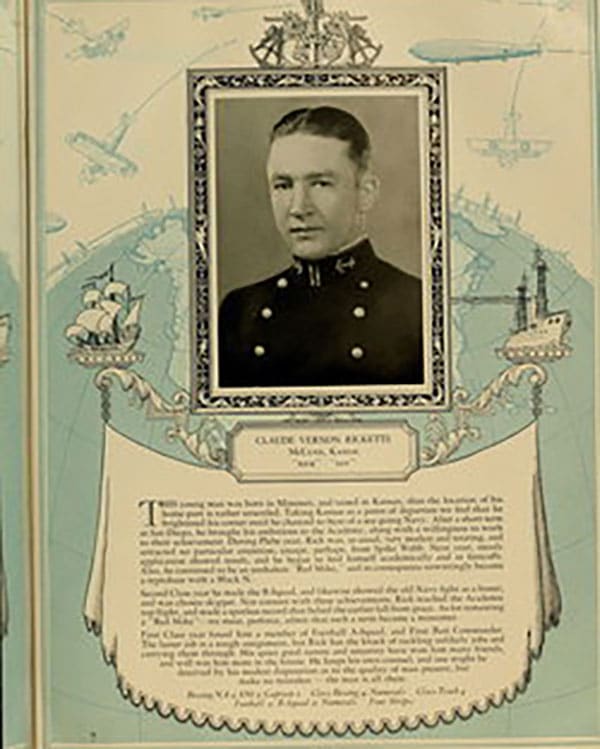

Claude Vernon Ricketts was the oldest son of Sarah Bertha and Gilbert Rickett, who lived a few miles west of Fair Grove, Missouri. He began his formal education at Windy Hill, a one-room school house. After completing the 8th grade in Fair Grove’s old two-story frame school house, Vernon moved with his family to McCune, Kansas, so he could graduate from the 12th grade. Then they moved back to Fair Grove, where Gilbert bought a farm just south of town.

“My boyhood was spent on the farm in days before modern power tools,” recalled Vernon. “Labor was largely human and animal muscle. The value of honest labor was so thoroughly impressed upon me that experience since has only emphasized that value rather than diminish it. I can think of no better environment to teach a lesson than the farm, where a boy can accept heavy responsibilities at an early age and can see so readily the results of his efforts.”

Retired Rear Admiral Myron Ricketts, says about his father, “After he graduated from high school, Dad told his folks that he wanted to join the navy, start at the bottom, and work his way to the top. He sure did that.”

In 1924, while he was at basic training in San Diego, California, Vernon Ricketts caught the attention of a junior officer, who thought he should try out for the Naval Academy. Being informed that he was too old, Vernon’s mother wrote to the Secretary of the Navy. According to Myron, his grandmother’s letter began with “My boy is a good boy…”

After Vernon passed through Naval Academy Prep School, he was admitted to Annapolis. He was captain of the boxing team, played varsity football one season, and graduated in the top 20% of the Class of 1929.

Vernon’s first assignment was on board the USS Lexington as a signal officer. He served at several duty stations, earned “wings” as an aviator, and was stationed aboard a destroyer, when he received orders to the USS West Virginia in September of 1941. His initial job was Damage Control Officer, but soon he was the ship’s Gunnery Officer.

While he was eating breakfast in the ship’s galley one Sunday Morning, Vernon heard “The Japs are attacking!” being yelled up and down the passageways. Of all the places in the world the USS West Virginia could have been on December 7, 1941, it unfortunately was tied-up at Ford Island, Pearl Harbor, Oahu, Hawaii.

According to the after-action report Lieutenant Ricketts wrote five days later, as the General Quarters alarm was going off, he felt the ship shaking due to bomb and torpedo hits. He ran to the Fire Control Tower. The door was locked, so he and his crew broke it open.

Vernon noticed that the ship was listing rapidly to the port side. He asked Captain Mervyn S. Bennion if he should “go below and counter-flood?” To which, Bennion said, “Yes, do that.”

While Vernon made his way down ladders and along passageways, he gathered others to help do the job. They avoided sailors carrying wounded men up to safety. The ship was listing so severely that its decks became impossible to walk across without holding on to something. With instructions from Ricketts, several crewmen began opening valves to let sea water into spaces on the starboard side which righted the ship as it slowly sank. It came to rest on the harbor bottom on an even keel with the main deck awash.

The USS Oklahoma had similar damage, but was not counter-flooded. It capsized, and was difficult to bring it up after the battle. Too badly damaged to repair at Pearl Harbor, the USS Oklahoma foundered and sank in the ocean while it was being towed to the United States.

After USS West Virginia settled upright in the mud, Ricketts went to a battery on the boat deck and found all of its ammunition had been expended. He formed an ammunition train by using a line of crewmen that passed shells one at a time from another magazine to the guns.

Informed that Captain Bennion was seriously wounded and needed attention, Ricketts told two men to get a pharmacists mate and meet him on the bridge. The Captain, still in danger of fire and smoke, ordered all others out to safer locations and refused to have them endangered by trying to save him. With the help of other sailors, Ricketts did however move the Captain out of immediate danger. At the same time he sent gun crews to the USS Tennessee to assist them in firing at Japanese planes that killed 2,402 Americans and wounded 1,232 others. Torpedoes and bombs that hit the USS West Virginia killed 106 of its sailors.

A large piece of metal had passed through the Captain’s abdomen. The pharmacists mate applied a bandage to the wound, as best he could, according to Ricketts. Bennion was put on a cot at first, but the sailors could not find a stretcher so he was strapped to a ladder and moved to several safe places to keep him from being burned to death or suffocating from smoke inhalation.

While fighting fires with little pressure in the hoses, Ricketts was informed that the Captain was about gone. After Bennion died from his wound, Ricketts ordered a line to be passed between the flag bridge and the starboard boat crane. This was because smoke and fire had trapped the crew on the bridge and they could not leave by ordinary means. The line was secured and allowed sailors, including Ricketts, to go hand-over-hand across it, before continuing to fight fires on several decks.

Ricketts’ early responsibilities on the farm, combined with training in the service, enabled him to react accordingly by providing ammunition to gunners and pulling the wounded Captain out of reach of fire and smoke.

In his report after the battle, Ricketts gave credit to personnel who worked with him. He said they carried out every order promptly and enthusiastically, even when it meant danger to themselves, and did not attempt to abandon the bridge until ordered to do so. Captain Bennion, who received a posthumous Congressional Medal of Honor, deserved highest praise for his noble conduct to the last, according to Ricketts, and although he was in great pain he kept inquiring about the conduct of the ship.

Among the sailors who assisted in saving the West Virginia from capsizing and helping the wounded Captain, Ricketts listed 2nd Class Mess Attendant Doris Miller. The twenty-two year old cook had been collecting laundry when General Quarters was sounded. His battle station was an antiaircraft battery, but when he got there he found it torpedo-damaged beyond use. Miller was ordered to assist with the loading of a pair of unattended antiaircraft guns. He took control of one of them and began shooting down Japanese aircraft, even though he had no training in operating a weapon. He fired until he ran out of ammunition and abandoned ship with the rest of the crew. He was the first African-American to receive the Navy Cross for his actions during battle. Miller died onboard the USS Liscome Bay at the Battle of Tarawa in November of 1943.

Vernon’s wife and sons, who had been in Oahu with him for three years, were living in California when they learned of the attack. His parents in Fair Grove, along with his brothers, had no idea of what had become of him for 2 or 3 weeks. In the youngest brother’s belongings, found after he died, there was a penny post card that had been passed by a Naval Censor with good news. It had been sent from Pearl Harbor Hawaii on Dec 10 1941, and said “I am well. Wishing you a very Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year. Love to all.” It was signed by Vernon Ricketts, so they knew he had survived the deadly attack. To help him Remember Pearl Harbor, even though it is difficult to read, Myron Ricketts has his oil-soaked birth certificate that was recovered from the battle-scene.

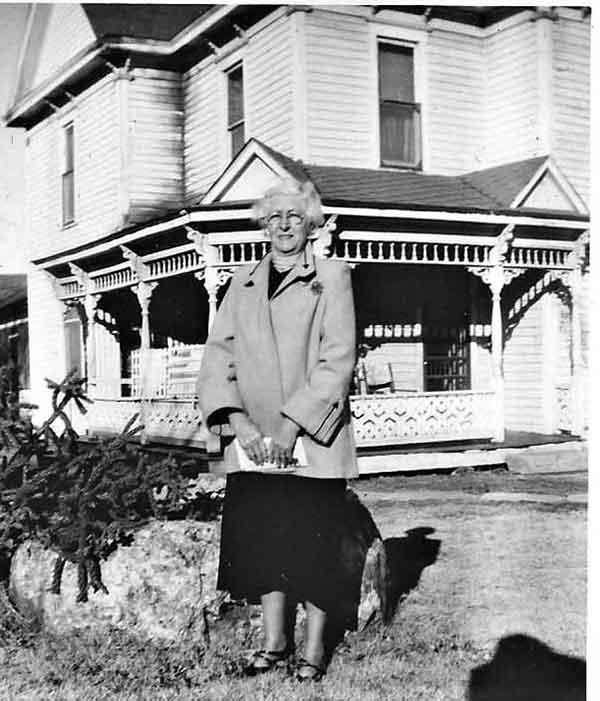

Myron, who stayed with his grandparents and attended school in Fair Grove for awhile when his parents were moving, says that his father, a rear admiral at the time, was on leave and helping his brothers build a bathroom in their parent’s home after the war. He remembers that they were still using an outhouse then because there was no inside running water. A flue pipe extended from the pot-bellied stove through the second floor of the house to heat the upper level. A newspaper reporter came to the construction site and asked to talk with the admiral, who he heard was visiting. He was really taken aback when one of Vernon’s brothers pointed at a man as dirty as he was, and identified him as the visiting naval officer.

Bill Anderson, of Springfield, who managed a gas company for many years in Fair Grove, said Admiral Ricketts was visiting his parents and came over to the propane plant one time. He paid for a new gas cook stove and water heater, and wanted them to be installed in their home. A few months after he put them in, Anderson saw the new cook stove sitting out on the porch. Mrs. Ricketts had apparently gone back to cooking with her old wood stove. She was no doubt used to it after all of those years of feeding working men on the farm, and it probably made better biscuits than the new one.

Following the Pearl Harbor attack, Ricketts was assigned duty onboard the battleship USS Maryland. It was involved in the assault of Tarawa. He wrote the book Myron says is still in use, on amphibious landings after watching numerous errors made in that battle.

Promotions came fast for Ricketts during the war. After it was over he took the family with him to Virginia and commuted to Washington, D.C. He was a student and then an instructor at the Naval War College in Rhode Island, Commanding Officer of a supply ship, then he took command of a heavy cruiser, the USS Saint Paul during which he was selected for a flag rank.

Olive, Missouri, resident Dean Jefferis was a sailor on the Saint Paul during the Korean War. Captain Ricketts found out he was from near his hometown, and invited him and his wife over for Thanksgiving dinner when they were in their homeport at Long Beach, California. “He was all spit and polish,” recalls Jefferis. “He made a good superior officer.”

Myron says that his father went back to the Pentagon, working in the Plans and Policy arena as a two-star admiral (Rear Admiral), before receiving his third star as commander of the Second Fleet out of Norfolk, Va. After a short ten months at this job, Ricketts made his fourth star when President John F. Kennedy appointed him as Vice Chief of Naval Operations. At that job he essentially ran the US Navy, because The Chief of Naval Operations dealt mostly with the Joint Chiefs. Vernon Ricketts started out as a “black-shoe sailor” but finally had worked his way up to a top position.

On July 6, 1964, the day after he attended a Pentagon garden ceremony, Admiral Claude Vernon Ricketts died at Bethesda Naval Hospital in Maryland. His son Myron was the last family member to see him alive. The USS Biddle (DDG-5), a guided missile destroyer, was re-named the USS Claude V. Ricketts shortly after his death. Ricketts Hall that contains the headquarters of the Naval Academy Athletic Association at Annapolis, berthing for visiting sports teams, athletic lockers, and an auditorium was also named for him.

Most of those who survived the attack on Pearl Harbor have since gone on, so it is up to us, the living, to remember the ones who died as well as acts of bravery done there on that historical day.

Related Posts

Make Toasted Ravioli at Home

This quick and easy recipe for St. Louis style toasted ravioli is perfect for your next party or potluck.

2020 Missouri State Fair Update

Although this year’s fair may look and feel a little different, the competition, fun, and fair food awaits.

7 Time-Honored State Fair Traditions

Each year there’s something new to see, and yet some components of the Fair date back from before Missouri actually had a designated State Fair. Let’s take a walk through time and look at some of the State Fair’s most proud traditions.