A single throw destroyed the legacy of Mansfield, Missouri native Carl Mays. He is the only major league pitcher who ever killed a batter with a pitch. Nearly a century later, two Mansfield women set out to win him some overdue recognition.

By Paul Cecchini

It began when Ann Duckworth of Mansfield wanted to write an interesting piece for her local writing group. An avid history buff, Ann visited the town’s newspaper office to pick the brain of the Mansfield Mirror’s then-editor Larry Dennis for story ideas. She initially considered the town’s most famous resident, author Laura Ingalls Wilder, but Dennis reminded Ann that the author wasn’t the only person of note from Mansfield. There was another: Major League Baseball player Carl Mays.

Mays, however, didn’t have a sterling reputation. His biggest claim to fame—or perhaps infamy—was being the only major league ball player who had ever killed a fellow player with a pitch.

Ann immersed herself in research on the pitcher, reaching out to courthouses, newspaper offices, and even visiting Carl’s old homestead outside of town, which he had built for his mom with money earned from one of his World Series wins. Today, that house is gone, but a wide set of concrete stairs leading to a nonexistent porch stands as a reminder of the home that used to be.

Born in 1891, Carl grew up in Prairie Hollow north of Ava, near the Douglas–Wright County line. His father passed away when he was 12, forcing Carl to drop out of school to support the family. He was able to earn money as a baseball player, first in semi-pro leagues, then in the minors. He made his major league debut with the Boston Red Sox in 1915, when he was 24 years old.

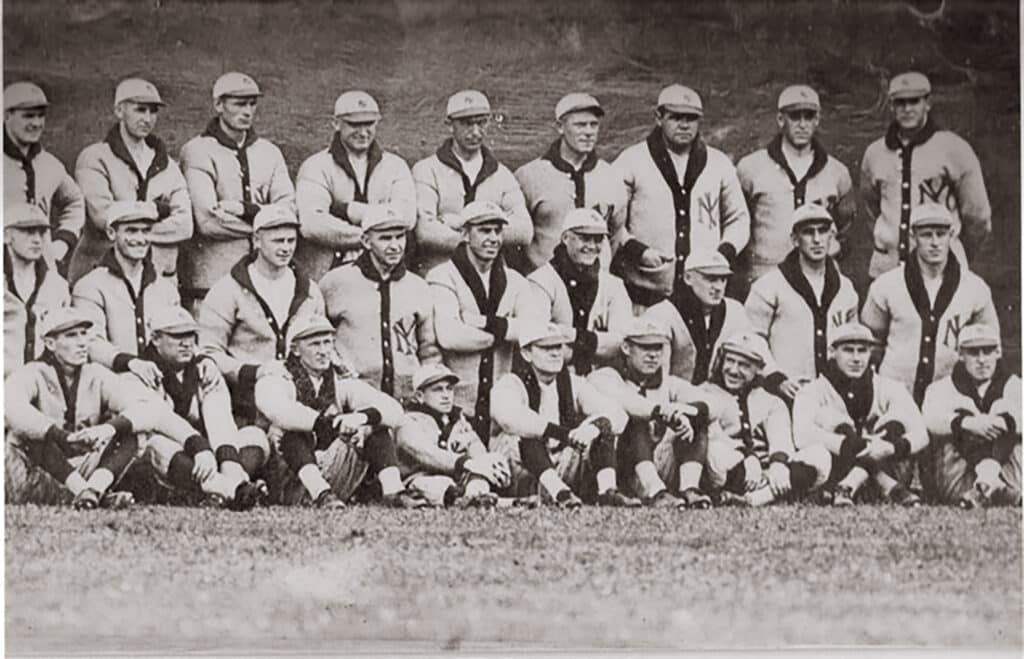

During his 15-year career in the majors, he played for the Red Sox, New York Yankees, New York Giants, and the Cincinnati Reds. While he started his career throwing overhand, he switched to a right-handed submarine pitch after an injury, and that earned him the nickname “Sub.” He was a contemporary of Babe Ruth and both were traded from the Red Sox to the Yankees—Carl in July 1919 and The Babe in January before the 1920 season. They were both present for the start of the fierce Red Sox–Yankees rivalry.

Photo courtesy of Mansfield Area Historical Society and Museum.

Carl tallied impressive career stats of 29 shutouts and 862 strikeouts in 490 games. He ended his major league tenure with a record of 208 wins and 126 losses. His 2.92 career earned run average stacked up well against a league average of 3.48 during that era. He made appearances in six World Series— three while with the Red Sox and three with the Yankees.

All his impressive statistics were overshadowed, however, by his pitch that killed Cleveland Indians shortstop Ray Chapman on August 16, 1920. The ball struck Chapman in the left temple, and he died later that night from his injury. Both Carl and the catcher maintained that Chapman leaned into the plate, apparently to attempt a bunt, and failed to step away in time. Carl was officially exonerated of blame.

The court of public opinion saw things differently. A player for the Detroit Tigers started a campaign to force Carl out of baseball. Other American League teams wanted to ban him. Some even refused to play against any team that Carl pitched for. Despite the cloud of controversy that followed him, Carl continued in the majors until 1929.

“Major League Baseball has put safety measures in place now,” Ann says. “We have glassed him into a box he can never get out of. He probably will always be the only pitcher to kill someone on the field.”

Most stories about Carl in the media would typically end there, ignoring his post-baseball life and skipping straight to his death in 1971. One morning sports report at the time claimed that he died “a bitter old man.”

But as time and research would bring to light, that could not have been further from the truth. Ann would soon learn that there was much more to Carl than the media portrayed.

Her piece was published in both the Mansfield Mirror and Douglas County Herald, but it didn’t feel like enough. She wanted to do more, and after driving by the Missouri Sports Hall of Fame in Springfield multiple times, an idea came to her.

Why couldn’t Carl Mays be there?

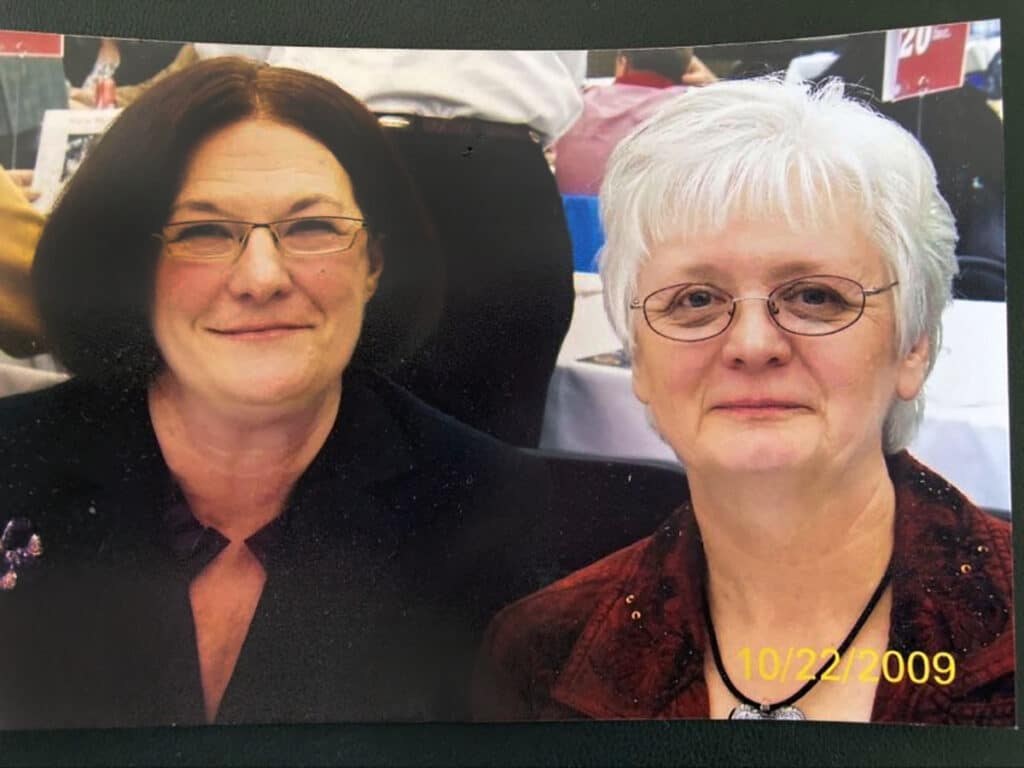

Unsure how to go about making it happen, Ann reached out to former classmate fellow history buff, Kathy Short, for help. The women went right to work, filling out the necessary application paperwork

and petitioning people from the Mansfield Historical Society board to local schoolchildren to write letters. They even spoke to the Missouri Sports Hall of Fame board, who were given custom-made portfolios complete with Mays’s picture on the front.

“I think the grassroots level wowed them,” Ann says.

Through their deeper research on Carl, they were able to make contact with several of his relatives and friends of the family, who shed greater light on him as a person, building their appreciation for the man behind the uniform.

They learned, for instance, that Carl was an avid fisherman. After retiring from baseball, he ran a fishing camp near the Missouri town of Manes. He used to fill his fishing waders with old, used baseballs and pass them out to the children. A family friend, Floyd Blankenship, remembered Carl visiting his parents’ house. To teach kids how to pitch, he would paint a target on an old cotton mattress and tie it to the fence.

Carl soon moved to Portland, Oregon, where he sold insurance for a time before opening the Jantzen Beach Carl Mays Baseball School on the Columbia River, which he kept open until World War II began. Carl relocated to the tiny town of Dayville, Oregon, on the Pacific coast and started renting out fishing cabins and boats. After the war ended, he returned to baseball in a new capacity: scouting for the San Francisco Seals, Cleveland Indians, and Milwaukee Braves. After retirement, he stayed in Oregon to hunt and fish alongside his wife, Esther. Carl passed away from pneumonia in 1971, at age 79.

One woman who knew Carl toward the end of his life told Ann: “He was the most wonderful storyteller, and of course we were delighted listening to him. To us, it was like having Babe Ruth in our living room. I’m sure he was saddened that he was remembered more for having thrown the pitch that killed a batter than for the fantastic pitcher he’d been, but he was a dear, kind man that we had the tremendous fortune to know.”

His grandchildren and great-grandchildren dearly loved him as well. “You could tell the depth of the sincerity,” Kathy says. “They would get teary-eyed when they would talk about him.”

Photo courtesy of Mansfield Area Historical Society and Museum.

Learning of Carl’s life off of the baseball field encouraged Ann and Kathy even more to get him the recognition he deserved. Things reached a tipping point when their campaign came to the attention of Associated Press writer Jim Salter, who penned a story about their efforts. Before long, the story was running in ABC News, USA Today, The Sentinel, and MLB.com—and other outlets, from Florida to Anchorage. What started as a local operation ballooned to national proportions overnight as letters encouraging Carl Mays’s induction into the Missouri Sports Hall of Fame began flooding in from across the country.

“I think they got letters from people who didn’t even know who Carl Mays was,” says Eric Dodson, president of the Mansfield Historical Society. “They maybe didn’t care that much about baseball, but after reading what the man had been through and all the negativity, they wrote in support.”

Then, in 2009, it happened. Carl was approved for induction into the Missouri Sports Hall of Fame.

More than 90 Mansfield residents turned out for the ceremony, including the entire high school baseball team. “It was just a very heartwarming night,” Kathy recalls. “It was like almost everybody in town was involved—people from all walks of life. As long as I live, I will never forget telling Carl Jr. that his dad was going to be in the Missouri Sports Hall of Fame. He became emotional and said, ‘You’re the only ones who ever did anything positive for my dad.’ Carl Jr.’s kids said that he called them and couldn’t even talk, he was crying too hard to tell them. It put such a light on the end of his life.”

The Mansfield Area Historical Society and Museum houses, to the best of the women’s knowledge, the only permanent Carl Mays exhibit in the country.

It started off simple, with a handful of public domain photographs that the crew found online. Then, as their Hall of Fame mission took off and they made contact with the family, things grew exponentially. Now, it showcases exclusive photos and audio tapes from the family’s private collection, as well as an autographed baseball and cigarette cards.

The museum offers free guided tours about the other Mansfield mainstay, Laura Ingalls Wilder, the Civil War, both World Wars, early pioneers, and the town’s former railroad and depot, drawing in tens of thousands of visitors yearly. But the Carl Mays exhibit is a tourist attraction in its own right.

“We have people come here from all over the United States just to see the Carl exhibit,” Kathy says. “They’ll drive 50, 100 miles out of their way just to talk to someone who knew part of his family. They get so wrapped up in it. They love the story. They love that the family is associated with it.”

According to Kathy, Carl’s granddaughter tells people, “I can tell you all the stories about Grandpa, but if you want to know something about baseball or how he grew up, you need to contact these ladies in Mansfield.”

Article originally published in the March/April 2023 issue of Missouri Life.

Related Posts

Wilson’s Creek National Battlefield is Established: April 22, 1960

On this date in Missouri history, Wilson’s Creek National Battlefield is established. The battle, the first in Missouri’s long Civil War history, took place on August 10, 1861, west of Springfield.

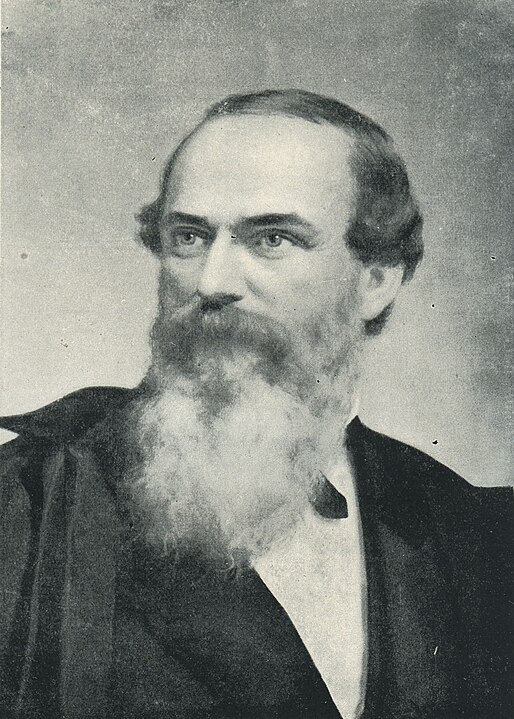

James Sidney Rollins is Born: April 19, 1812

James S. Rollins was born on this day. Many recognize Rollins as the Father of the University of Missouri.

Game On!

They say the house always wins, but community takes the jackpot at Vintage Vegas Casino Night. Sponsored by Vision Carthage, the event features food, drink, and plenty of casino-style fun. Proceeds benefit local charitable initiatives.