This article was originally published in our July/August 2021 issue.

The Missouri State Park system spans the gamut of Missouri’s hallmark landscapes and ecosystems, and it also preserves a great deal of our state’s history. If you’ve had a chance to go out and experience Missouri’s parks and historic sites yourself, you probably wouldn’t be that surprised to learn that individual parks as well as the system itself have been ranked among the best in the country. At Missouri Life, our love for the state park system runs deep, which is why we published a massive four-hundred-plus-page coffee table book about them and a condensed version of that larger volume a little later. The shorter version of the book sold out within months, and it’s gotten to the point where even our own staff have a hard time wrangling a copy. So, we decided to print some more of them. In celebration of the book’s second edition, we’re publishing an essay of photos from our state parks books, replete with captions from the freshly updated guide, which you can purchase at MissouriLife.com/shop.

Roaring River

It doesn’t “roar”—but it once did. The spring once gushed from a cleft in the dolomite bluff, twenty million gallons daily that tumbled and cascaded over, under, and around a rocky escarpment, down to the streambed below. But in the 1930s, the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) built a dam in front of the cleft in the bluff, and the cascade was submerged beneath the deep, blue pool we see today. A small trickling flow from the bluff high above falls into the pool, spraying and refreshing the clumps of ferns, columbines, and mosses that line the dolomite ledges that extend into the shallow, cave-like cleft in the rock. This grotto of blue and silver water, gray rock, and delicate green ferns in quiet indirect light is as lovely a scene as any in the park system. Roaring River is stocked regularly, and the park offers premier trout fishing in a breathtaking setting: a deep, narrow valley framed by high, forested slopes—the look of mountainous terrain.

Prairie

Fall must be the prettiest season on the prairie. Emerald-green grasses turn brilliant orange, red, bronze, and gold. During the summer, they whisper or rustle in the wind. In fall, they rattle and toss to and fro. The land seems restless and alive, its color more intense and consuming than that of forests. Standing in a swale in the midst of this rolling sea of grass, facing the wind and knee-deep in prairie asters, you are just a speck on land that must stretch to somewhere beyond forever. And all around you, engulfed by the open skies, the annual fall pageant of the prairie begins. First, there are the northern harriers—prairie hawks that the fall prairie attracts like a magnet. Sometimes near, sometimes far, the hawks glide low, slowly skimming over the top of the grass. Or they hover, suspended, barely cresting some windy knoll—listening. Beneath the prairie hawks, the bison are in a world of their own. In fall, they are in their best condition of the year. It’s also breeding season, and the bulls are touchy and cantankerous. Sometimes they fight. The ground shakes and the dust flies when two one-ton animals slam full speed into one another. Deer seem to sprout in the openness. The early morning sun highlights them and sometimes you become aware of a collection of eyes, ears, and noses—each looking your way. But since only their heads show, motionless at the surface of that tossing, grassy sea, they look strangely suspended, almost as if the heads are rooted while the land moves around. This is the essence of Prairie State Park, one of the few places left where this tallgrass drama still unfolds so completely. And it happens not just in fall, but daily, with a progression of sights and sounds that become a song of the seasons—living visions of Missouri’s natural past preserved in this park.

Graham Cave

Above the Loutre River in the hills a few miles north of the Loutre’s confluence with the Missouri River is an outcrop with a large cave created at the contact zone between St. Peter sandstone and Jefferson City dolomite. Caves in dolomite or limestone are common enough, but a sandstone cave is less common. What is noteworthy, though, is not so much the cave, rare as it is, as what has been found in the debris on its floor. Dr. Robert Graham, a Scotsman who came to Missouri from Kentucky in the wave of migration that followed the War of 1812, settled in the area in 1816 and purchased a portion of rich bottomland along the Loutre River. In 1847, he acquired from the federal government the parcel of land containing the cave. From 1949 through about 1955, archaeologists Wilfred Logan and Carl Chapman of the University of Missouri and the Missouri Archaeological Society conducted extensive excavations in the cave. The results were staggering. Within a deep portion of the deposits, they found evidence of the oldest known humans in Missouri up to that time. The extremely significant discoveries at Graham Cave, including not only the oldest materials but also the remarkable evidence of ways of life and adaptations to the environment over ten millennia, were recognized when Frances Graham Darnell took pride in the discoveries made on her land and donated 237 acres—land that had been in her family for nearly a century and a half—to the state in 1964.

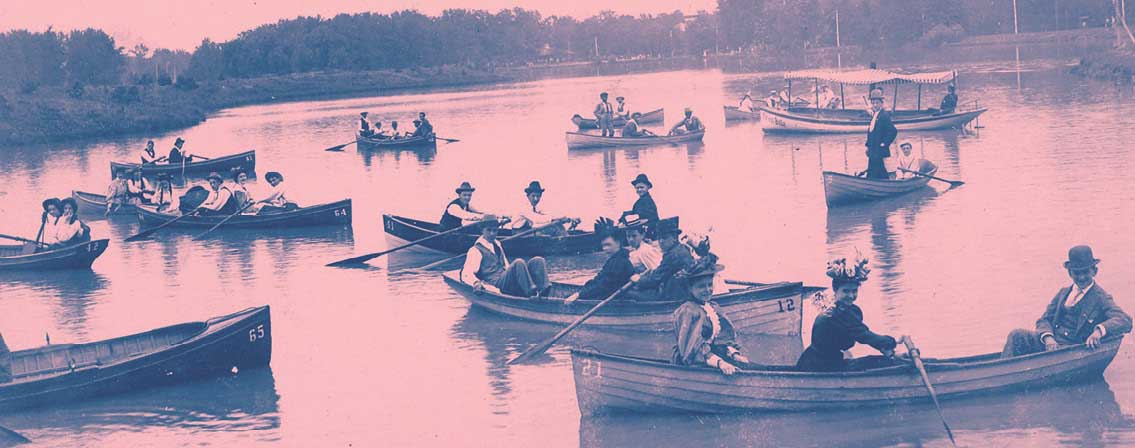

Castlewood

St. Louisans flocked by the thousands to the Castlewood area from 1915 to about 1940 for weekends of canoeing, swimming, dancing, partying, and some gambling. After World War II, many of the hotels and clubhouses declined, and the natural beauty and recreational value of the lower Meramec River went unappreciated as the area became a kind of industrial dumping ground. In 1975 Gov. Christopher Bond announced a plan to coordinate the recovery of more than a hundred miles of the lower Meramec River. The centerpiece of this effort was and is Castlewood State Park, which offers more than thirty miles of hiking and biking trails, eleven of which are open to horseback riders. One of the park’s key features is the old Lincoln Beach, a sandy byproduct of the Union Sand and Gravel Company’s gravel-mining activity in the river upstream. On the south side of the river near the old community site of Morschels is a stand of native bottomland forest. Most such stands were long ago cleared away for agriculture or industry, but here at Castlewood, the visitor can still experience the feel of a mature floodplain forest with its silver maple, box elder, black willow, white ash, sycamore, slippery elm, and hackberry. The legacy of grand weekend recreation that once defined Castlewood State Park is still alive and well here, and the park has also become a testament to environmental stewardship.

Bollinger Mill

The Burfordville Bridge spans the Whitewater River just upstream from Bollinger Mill in an area that was a wilderness in the 1790s when George Bollinger arrived. Bollinger received a Spanish land grant on condition that the land be developed and settled. He built the first mill and dam of logs at the turn of the nineteenth century, and he also brought twenty German and Swiss families from his home state of North Carolina to the settlement along with German-speaking slaves of their households. Bollinger would go on to serve as an officer in the War of 1812 and a statesman. After Bollinger died in 1842, his family operated the mill until September 1861, when it was razed by Union troops in retaliation for an attack carried out by one of Bollinger’s Confederate grandsons. In 1865, Solomon R. Burford rebuilt the mill, the four-story structure full of milling machines that visitors enjoy touring today. The mill ceased commercial operation around 1948, but its machinery has been painstakingly restored for demonstrations. Today, Bollinger Mill and Burfordville Covered Bridge provide the visitor with a step back in time to experience genuine grist milling, a stroll through the oldest covered bridge in Missouri, and a peaceful rest along a tree-lined stream.

Trail of Tears

Although looking out from the bluffs at the Mississippi River at Trail of Tears State Park today offers a vision peaceful and sublime, it once overlooked one of the saddest episodes in American history. That infamy gives the park its name. Here at Moccasin Springs in the fall and winter of 1838 and 1839, nine contingents of Cherokee were ferried across the icy Mississippi River, a formidable obstacle on the forced march from their Appalachian homeland to a new home in what is today Oklahoma. The park’s extensive forests, despite some early logging, resemble the great woods of the Cherokee homeland. From the Mississippi, the Cherokee took three routes across Missouri; portions have been marked as part of the Trail of Tears National Historic Trail, established in 1987. Roughly one of every four Cherokee died in holding stockades or during the forced migration. The remainder arrived a broken and politically divided people. In spite of everything, the Cherokee built a remarkable society in their new homeland and continue to survive as a nation within a nation. Trail of Tears State Park was a gift to the state by the people of Cape Girardeau County, who authorized a $150,000 bond to purchase more than 3,000 acres in 1956. A handsome visitor center provides exhibits on the natural history of the park and on the Cherokee tragedy. The park is a superb preserve of an original Mississippi River landscape. It is also a sober reminder of the intolerance of a young country and a memorial to a resilient people who persevered.

Battle of Island Mound

At Missouri’s western edge, the hills that seem to roll in from Kansas don’t amount to much, but a small hill commands a big view. It is this landscape where Black Americans fighting in the Civil War earned their place in Missouri—and national—history. The boundary between Kansas and Missouri runs through this country, and while only a line on a map, it was an important line, a significant part of the great national debate—a free soil territory on one side, a slave-holding state on the other. About nine miles east of this border in Missouri lay the Toothman farmstead, the site where on October 27, 1862, 240 blue-clad, Black Union soldiers, the First Kansas Colored Volunteer Infantry, encamped and dubbed the camp Fort Africa. They had been sent to clear out a nest of pro-Southern guerrillas who occupied the ground between a channel of the Marais des Cygnes River and one of its wandering sloughs as a place of refuge and rest and for storage of supplies and loot. And so they did. The Kansans were outnumbered about two-to-one by some four hundred mounted rebel guerrillas. On the flank of the river mounds, still a mile short of Fort Africa and no cover in sight, the beleaguered African American soldiers formed up and got off one volley of musket fire after another—as the rebel cavalry crashed into and over them—until the horsemen withdrew. It wasn’t much of a battle, but it was the first time in the Civil War that former slaves had taken up arms as soldiers on the battlefield. Acting against President Abraham Lincoln’s wishes and Secretary of War Edwin Stanton’s orders, Kansas Senator Jim Lane, a radical instigator of many ugly border incidents, assembled two regiments of Black Americans in 1862 as Kansas units. It was one of these regiments, not yet part of the federal army, who prevailed at the Battle of Island Mound.

Photos // Kyle Spradley, Scott Myers, Ben Nickleson, Jim Diaz, Missouri State Parks, Denise Dowling

Related Posts

Book Review: Great River City

A new coffee table book looks beneath the surface of St. Louis’s river history

A Walk Through Missouri’s Largest Municipal Parks

Forest and Swope Park both rank among our nation's largest city parks by acreage, and both played important roles in the development of their communities.

See Our Vanishing Roadside Parks

After some investigating, I found Karen Daniels, senior historic preservation specialist for the Missouri Department of Transportation. She’s the expert on the state’s roadside parks.