Missouri has produced several renowned general officers and interred a number of others. Let us take a brief look at a few of the feats and foibles that mark the lives and careers of three of these generals—Alexander William Doniphan (1808–1887), James Shields (1806–1879), and John J. “Black Jack” Pershing (1860–1948).

Will Doniphan Saves the Mormons

For years, it seemed that everywhere Joseph Smith, founder of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, led his members, they were met with resistance, hostility, or outright violence. In 1831, he sent a small party of his followers to western Missouri to build what he envisioned as New Jerusalem and to prepare for the imminent Second Coming of Christ. They chose to settle in Jackson County, near present-day Independence, but incurred the displeasure of the other Christians who had arrived before them.

The locals had what they felt was cause for resenting the interlopers. For one thing, these Mormons, as they were being called, came as missionaries, seeking converts and preaching a different faith than their own. As the Mormon’s numbers began to grow, so too did the hatred toward them. Animosity toward the Mormons soon became a political as well as a religious issue. Demonstrating a unity of purpose, the Mormons tended to vote as a bloc. Also, many if not most of Smith’s flock had come from antislavery Northern communities, whereas Missouri had recently entered the Union just a few years earlier as a slave state. And finally, there was the issue of polygamy.

In 1833, local mobs drove the Mormons out of Jackson County and into adjacent Clay County. Predictably, this did little to curb local ill will. As described by Missouri historian James F. Muench, “Angry neighbors attacked the Mormons, tearing down their houses, beating their men, and threatening their women and children with death if they did not leave.” In an effort to quell the violence, in 1836, the Missouri state legislature created Caldwell County specifically for the Mormons, who built a city there that they named Far West.

By 1838, hostilities boiled over. During the Mormon War, the Mormons were attacked, and their towns, homes, and places of business were looted and burned. In several instances, the Mormons responded similarly. Rather than quelling the violence, Lilburn Boggs, governor of the state of Missouri, issued an Extermination Order, stating that “the Mormons must be treated as enemies, and must be exterminated or driven from the State if necessary for the public peace.” Panicked, Mormons left their homes in droves and sought safety in Far West, where Smith had also recently settled.

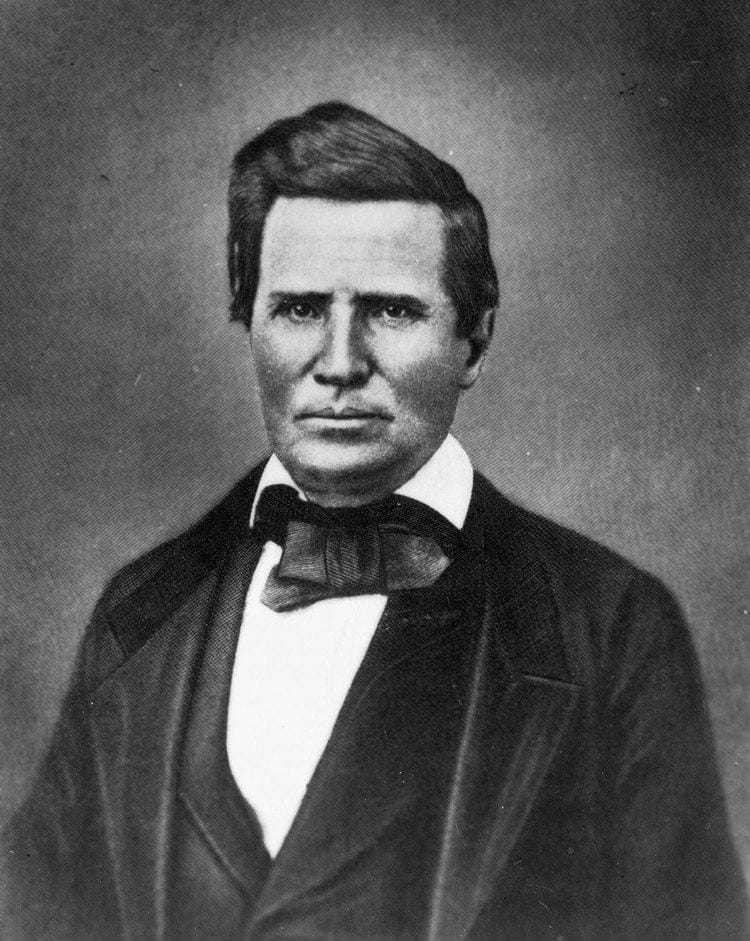

Governor Boggs then called out the state militia, ordering Brigadier General Alexander William Doniphan to secure the arrest of the Mormon leaders, including Smith. Boggs had chosen the best person for the task.

Born in Kentucky in 1808, Will Doniphan moved to Liberty where, after acquiring a law degree, he opened a practice. Although he did not share in the Mormon beliefs, he strongly believed in their right to practice their religion, as is guaranteed by the Constitution. When the Mormon troubles began, he had represented them in court—albeit, unsuccessfully—in an attempt to block the order mandating their expulsion from Jackson County.

Following Governor Lilburn’s orders, Doniphan arrested the Mormon leaders, but through mediation rather than violence. In a moment when mayhem might well have ensued, Doniphan opted for a peaceful resolution and avoided further bloodshed by convincing the Mormons to surrender voluntarily.

After their surrender, Smith and his fellow leaders were charged with treason—a capital offense—and brought before a hastily convened court martial. The trial was a formality and the verdict a foregone conclusion: All were convicted and sentenced to death by firing squad. Doniphan’s commanding officer, Major General Samuel Lucas, ordered him to personally carry out the executions.

Doniphan refused the order and impugned the legality of the court, stating that not all the members were military officers, whereas the defendants were all civilians. He then went a step further, stating in a letter to General Lucas, “It is cold-blooded murder. I will not obey your order. My brigade shall march for Liberty tomorrow morning, at 8 o’clock; and if you execute these men, I will hold you responsible before an earthly tribunal, so help me God.” Lucas transferred the case to a civilian court in Columbia, where Doniphan again represented the Mormon leaders. Eventually, all the Mormon defendants, including Smith, were either released or allowed to escape. Smith shortly made his way to Illinois to start anew, only to incur the same resistance from the local population there. He and his brother were arrested for treason once again, but this time, a mob of around 200 locals stormed the jail and killed them both.

Standing up for your neighbors’ enemies is generally a way to destroy one’s career. Surprisingly, however, Doniphan was so highly regarded that his defense of the Mormons had little to no negative effect on his standing in either the community or the state. His legal practice flourished, and he was elected to the Missouri House of Representatives on three separate occasions. Doniphan’s career following the Mormon War was impressive. At the outbreak of the Mexican-American War (1846–1848), he enlisted as a private in the Army but was shortly voted to the rank of colonel by the men of his regiment and was also named commander of the First Regiment of Missouri Mounted Volunteers. According to Muench, “In one year, Doniphan’s unit … [marched] more than 3,500 miles by land and traveled another 1,000 by water; fought two battles in Mexico; established an Anglo-American-based government in New Mexico; and paved the way for the annexation of the territory that became New Mexico and Arizona.”

Doniphan was also a study in contradictions. When the country was divided by the Civil War, as a devoted pro-Union constitutionalist, he worked diligently to keep Missouri from seceding, and yet, he was a staunch proponent of the institution of slavery and was himself a slave owner. Despite this, President Lincoln sent him as a delegate to the 1861 Washington Peace Conference and named him a commissioner of claims in 1863. Doniphan subsequently moved to St. Louis, and after the war he moved to Richmond, Missouri, where he practiced law until his death in 1887. Today, he is mainly remembered as the man who saved the life of Joseph Smith … if only briefly.

James Shields (Sort of) Whipped Stonewall Jackson and Challenged Lincoln to a Duel

The inscription on the monument for Brigadier General James Shields at his grave in St. Mary’s Cemetery in Carrollton reads, in part, “United States Senator from Illinois, Minnesota, and Missouri.” He is, in fact, the only person in American history to have served as a US senator from three states. This provides but a small window into Shields’s fascinating life.

When Shields immigrated to Illinois from his native Ireland in 1827, he brought with him an irascible disposition and a highly inflated self-image. One historian described him as “an

exceptionally vain and ambitious egotist.” As a practicing attorney, Shields once beat his opponent over the head with a law book, stating, “If you have no law in your head, I’ll beat some into it!”

As a dedicated Jacksonian Democrat, he served in the Illinois legislature, and he served as state auditor on the Illinois Board of Public Works. In late 1842, inspired by a controversial financial statement authored by Shields, three anonymous letters signed by “Aunt Rebecca” were printed in the Sangamo Journal, and all were brutal in their ridicule of Shields. One letter referred to him as a “conceity dunce” and “a fool as well as a liar.” Another letter conjured an imaginary meeting between Shields and a group of young women: “Dear girls, it is distressing, but I cannot marry you all. Too well I know how much you suffer; but do, do, remember, it is not my fault that I am so handsome and so interesting.”

Shields was apoplectic. As a result of the assault on his pride and manhood, he became a laughingstock among his fellow townspeople. As it happened, at least one of the letters was penned by a fellow Springfield attorney and devoted Whig named Abraham Lincoln. Needing little encouragement, Shields demanded satisfaction and challenged Lincoln to a duel.

Lincoln found himself in an untenable situation. Either he would be killed, or he would kill a fellow human being. In his mind, neither option was acceptable. Nonetheless, he accepted the challenge, while secretly seeking to find a way out of the situation. Since he had a choice of weapons, and knowing of Shields’s prowess with pistols, Lincoln chose cavalry broadswords. The broadsword blades were three-and-a-half feet long and sharpened from point to hilt; Lincoln reasoned that at his six-foot-four height, his reach alone would keep the five-foot-nine Shields at bay. When Shields protested that the weapon of choice was “barbarous,” Lincoln responded, “So is dueling.”

Since dueling was illegal in Illinois, the party reportedly repaired to an island in the Missouri River owned by the more tolerant state of Missouri. Fortunately, calmer heads prevailed, and before the blades were drawn, Shields settled for an explanation and apology from Lincoln. Interestingly, afterward, Shields and Lincoln became friends.

At the outset of the Mexican-American War in 1846, Shields raised a regiment and was commissioned as a brigadier general. His military service during the conflict was exemplary; he commanded a brigade at the battles of Vera Cruz, Cerro Gordo, and Chapultepec and was twice wounded. In acknowledgment of his service, Shields was breveted to the rank of major general.

When the Civil War began, he was again assigned the rank of brigadier general, serving in the Department of the Shenandoah under Major General Nathaniel Banks. Shields’s earlier military record worked in his favor, and he was champing at the proverbial bit to demonstrate his strategic prowess and win laurels and a promotion through combat. On March 23, 1862, at Kernstown, Virginia, he got his chance.

Tiny Kernstown sat at the head of the strategically vital Shenandoah Valley, and it was the legendary—and heretofore undefeated—Confederate General Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson’s mission to keep the valley out of Union control. On this particular day, Jackson’s cavalry was conducting reconnaissance in the area and reported that the Yankees were on the move. The 4,200 men of Jackson’s First Virginia “Stonewall” Brigade were dramatically

outnumbered by the 38,000 Union soldiers marching in his direction, and Jackson wisely chose to retreat southward. Major General Banks then sent Shields’s 7,000-man division in pursuit.

When Jackson’s artillery opened up on Shields’s position, he responded by ordering Colonel Nathan Kimball to drive the rebels from the area, while at the same time sending a brigade north as a ruse to confuse Jackson. It was a clever strategy. The deception worked as intended, but by this time, Shields—whose arm had been broken by a shell fragment—was obliged to turn the command of his division over to Kimball.

In the desperate fighting that followed, Kimball performed brilliantly, driving the Stonewall Brigade into a panicked retreat—a first for the redoubtable Jackson. Shields, however, was unwilling to concede that Kimball was the driving force behind the rout. Military historian David G. Martin wrote, “Beginning that night and continuing to the end of his life, Shields bragged that he was the only Union general to defeat Jackson in an open battle. While technically correct, the honor, if not the rank, more accurately belonged to Kimball.” Apparently, the US Department of War agreed, elevating Kimball to the rank of brigadier general. To be fair though, Kimball did follow the strategy that the incapacitated Sheilds had outlined.

The day after the battle, Shields was promoted to the rank of major general. However, for reasons that remain vague, the Senate reconsidered and rejected the appointment, and the promotion was withdrawn. With his pride injured, Shields resigned from the army. According to biographer H. A. Castle, President Abraham Lincoln then offered the bristly Shields command of the Army of the Potomac, but Shields refused the offer because of the animosity that existed between himself and President Lincoln’s Secretary of War, Edwin M. Stanton.

Between 1863 and 1866, Shields moved four times, to San Francisco, the Mississippi Valley, Wisconsin, and finally, Carrollton, where he continued his law practice and lived out the rest of his life. He ran for election as senator in 1868 and lost. Eight years later, he was offered the position of doorkeeper for the US House of Representatives, which he refused, considering the position beneath him.

He did, however, serve a term in the Missouri House of Representatives. In 1879, Shields was chosen to serve out the few remaining months of the recently deceased Missouri Senator Lewis V. Bogy’s term. When Shields died that same year, his body was accompanied to St. Mary’s Cemetery by two infantry companies and a brass band. Today, a statue of Shields stands in front of the Carroll County Courthouse.

Shields was undeniably courageous, an effective military leader, and a dedicated politician. He was also a man whose thin skin, hair-trigger temper, and overabundance of personal pride blocked potential advancements throughout his life and career.

“Black Jack” Pershing and His Mexican Wild Goose Chase

Periodically over the past two centuries, our relations with Mexico have been, to say the least, volatile. And when the Mexican Revolution erupted just across our southern border in 1910, America inevitably became involved.

By this time, former army officer President Porfirio Díaz had been the iron-fisted dictator of Mexico for some 33 years, and the Mexican people were clamoring for change. Although Diaz was soon driven out of office, the next 10 years of armed revolution would be notable for a level of chaos and violence that the country had never before experienced. Beginning with the diminutive, hopelessly naïve Francisco Madero, who anointed himself as national leader, there was a dizzying progression of military and political national figures who would either be driven into exile or to early graves.

One of the most prominent of these self-appointed saviors was a charismatic small-time cow and horse thief turned general named Doroteo Arango. While running from the authorities, he had begun calling himself Francisco “Pancho” Villa, and when he joined the

revolution, it was under this name that he rode at the head of a paramilitary army of several thousand soldiers and guerrillas. For a time, his Division del Norte, or Division of the North, controlled much of northern Mexico. Villa loved the spotlight and went so far

as to sign an agreement with a Hollywood production company to film his exploits in the army.

As the revolution progressed, Villa’s relations with the United States, and particularly with President Woodrow Wilson, went from cordial to fractious. Although Wilson initially wooed Villa, the likeliest potential ally south of the border, he soon spurned the rebel

general in favor of the more politically savvy Venustiano Carranza. Wilson even went so far as to provide support to Carranza’s army, enabling it to decisively crush Villa’s forces.

In January 1916, a furious Villa saw this as a betrayal on Wilson’s part and executed 16 American citizens in Santa Isabel in northern Mexico. Two months later, he led nearly 500 of his fighters across the border and into the United States, attacking Columbus, New Mexico, burning army barracks, stealing horses and ordnance, and killing some two dozen or so US citizens, including several soldiers.

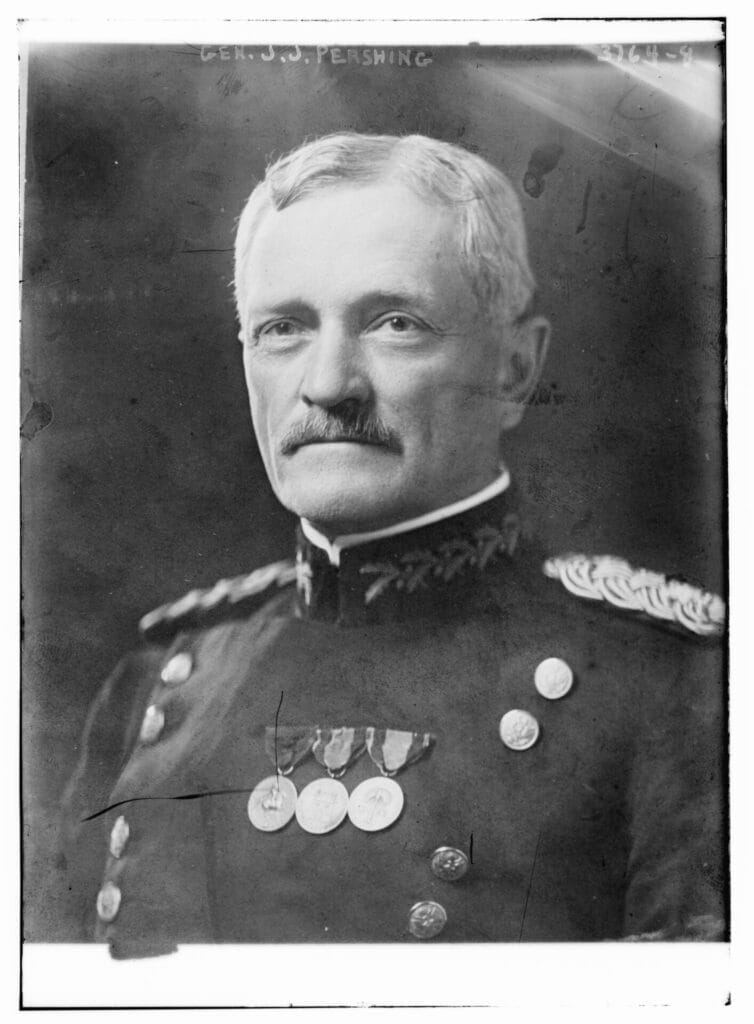

Wilson was stunned. The attack by Villa’s guerrilla army essentially constituted a foreign invasion of the United States—arguably the first such event since the War of 1812. The federal government ordered a so-called Punitive Expedition into Mexico, for the express purpose of capturing or killing the popular leader and dispersing his rebels. A combined force of several thousand men was assembled, and the man selected to command the mission—unofficially being referred to as the Pancho Villa Expedition—was one of the ablest commanders in the US Army, Brigadier General John Joseph “Black Jack” Pershing. (He had acquired his nickname from having commanded African American troops with the Tenth Cavalry in Montana.) Pershing was born on a farm in Laclede in 1860, the year before the start of the Civil War. After graduating from Missouri State Normal School of the First District, he studied at West Point, later teaching courses there as well. He received a law degree from the University of Nebraska, where he taught courses in military science. He went on to establish a reputation as a “soldier’s soldier,” serving in command positions in the American Indian Wars, Spanish-American War, and conflict in the Philippines. In addition, he had served as military attaché to Japan and a military observer of the Russo-Japanese War, in 1904–1905. “Black Jack” Pershing was the logical choice to lead a punitive mission into Mexico. Pershing crossed the southern border on March 14, 1916—just five days after Villa’s attack on Columbus, New Mexico—at the head of thousands of American troops, mainly cavalrymen. Carranza strongly resented Pershing’s incursion and refused to assist the expedition. Over the next 11 months after the invasion, the two nations veered dangerously close to war.

In June 1916, Carranza’s troops engaged Pershing’s forces at the village of Carrizal, resulting in 22 American and 30 Mexican casualties. Meanwhile, Pershing’s forces moved ever deeper into Mexico, but the elusive Villa was nowhere to be found. At this time, World War I was raging in Europe, and in 1917, Germany made an overture to Carranza, who had become the president in 1917, to form an alliance. Pershing was advised that while pursuing Villa, he was to do nothing that would propel Mexico into this alliance. President Wilson had specifically instructed Pershing to act “with scrupulous regard for the sovereignty of Mexico.” This proved a virtual impossibility since once Pershing crossed the border, he and his command had effectively invaded Mexico.

Serving as an aide to Pershing when he entered Mexico was a brash young lieutenant named George S. Patton. The long, lean, and ambitious Patton, who grew up a child of privilege and attended West Point, had pressed Pershing relentlessly for the position ever since he first heard about the campaign. Biographer Michael Lee Lanning described Patton as “audacious, flamboyant, brave, tough, single-minded,” adding, “He was also … arrogant, egomaniacal, profane, quick-tempered, and racist.”

Accompanying Pershing’s cavalry were several Dodge touring cars and some 262 cargo trucks, making this the first time in US history that a mechanized force invaded a foreign country. Foreshadowing his World War II role as a brilliant tank commander, the 30-year- old Patton wholeheartedly embraced the new technology of the automobile. On one occasion, while on a foraging mission, Patton—along with three carloads of soldiers and scouts—encountered three Villistas, or followers of Villa. A short battle ensued, in which all

three bandits were killed. Although there was no indication that Patton had fired a fatal shot, he carved two notches in one of the ivory grips of his engraved Colt .45 six-shooter. He then drove back to headquarters with the bodies of the bandits.

As it turned out, Patton’s Old West style gunfight, which proved to be an instant sensation in the American press, was a rare military high point of the expedition. After fruitlessly pursuing Villa into Mexico’s northern mountains and across its arid plains and having engaged in several skirmishes with both insurgents and Carranza’s federal forces, Pershing was ordered to bring his army home.

Ultimately, Villa abandoned the revolution and retired to his large ranch outside the city of Hidalgo del Parral. On July 20, 1923, as he was being driven through town, Villa, his two bodyguards, and his driver were ambushed and killed. Thus, a handful of homegrown

assassins accomplished in minutes what “Black Jack” Pershing—arguably the greatest general of his time—and thousands of American troops had failed to achieve in nearly a year.

With the exception of the Pancho Villa debacle, Pershing’s military career was nothing short of stellar. When America entered World War I, President Wilson named Pershing, then a major general, commander of the American Expeditionary Forces in France, where he won laurels for bravery and his victories. In 1919, he had the singular honor of being named General of the Armies. Pershing served as Chief of Staff of the United States Army from 1921–1923, retiring from active service the following year. After retirement, he wrote a memoir—which won a Pulitzer Prize. Apparently unable to remain inactive, Pershing was named chairman of the American Battle Monuments Commission, 1923–1948.

This article was originally published in the November/December 2024 issue of Missouri Life.