“Future generations will say, ‘We had a home once and I wish my people had held that land.’ ” —Little Turtle, Otoe-Missouria Tribe, April 1895

The US Bureau of Indian Affairs states unequivocally, “There are no federally recognized Indian tribes in Missouri today.” This is not surprising. In the early 1800s, the government of the recently formed United States began a concerted program to remove and relocate Indians. Beginning with the administration of America’s third president, Thomas Jefferson, the various tribes of Missouri and neighboring states and territories were lied to, bribed, bullied, and ultimately forcibly uprooted and driven onto smaller tracts of land, primarily in Nebraska, Kansas, and what would later become the state of Oklahoma. Once there, they were preyed upon by dishonest Indian agents and traders. Well-intentioned missionaries also helped destroy their native cultures.

More damaging were the whiskey peddlers. The distillers and purveyors of illegal bootleg spirits promoted their own brand of tribal destruction. Michael Dickey, site supervisor of Arrow Rock State Historic Site and a historian on the Missouria tribe, writes: “Following warfare or an epidemic, recovery was possible, but there could be no recovery from liquor.” A Methodist missionary observed the Indians’ “principal vices are emphatically our vices. If they get drunk it is upon our whiskey … and yet we claim to be ‘civilized’ and freely deal out to them the epithet ‘savage.’”

The native tribes’ greatest nemesis proved to be the US government. In the many treaties signed by the United States, the tribes were promised payment in the form of cash and trade goods. The amounts themselves were pitifully small.

David J. Wishart, acclaimed author of An Unspeakable Sadness: The Dispossession of the Nebraska Indians and Great Plains Indians, surveyed Indian Claims Commission case data and determined that the tribes of the central and northern Great Plains were offered, on average, 10 cents per acre—a fraction of the dollar or more that comparable land was selling for at the time—“for the cession of some 290 million acres of land.”

The US Office of Indian Aairs was responsible for overseeing the terms of the treaties. Corruption was rampant. Many of the trade goods were substandard and overvalued by several times their worth, and the promised payments often were never seen—unsent, stolen by Washington functionaries, or simply given directly to crooked traders and Indian agents.

Of the money that was forthcoming, Overton’s article states that a major portion of the allocated funds were paid, at federal discretion, for “‘non-Indian expenses”— salaries for white farmers, laborers, hostlers, blacksmiths, and instructors, as well as payment for employee housing and furniture. In 1964, the Indian Claims Commission awarded the current generation of Otoe-Missouria nearly $3 million, in compensation for earlier “unconscionable” and “unfair” payments.

In the second half of the 1800s, federal policy changed, in the words of Osage chronicler David Grann, “from containment to forced assimilation. Officials increasingly tried to turn the [tribes] into churchgoing, English-speaking, fully-clothed tillers of the soil.” Annuities that had been promised to the tribes—and were often paid in clothing and food rations—were withheld pending their adoption of a totally agrarian way of life. As one Indian Aairs commissioner declared, “The Indian must conform to the white man’s ways, peacefully if they will, forcibly if they must.”

One of the first traditions to disappear was the annual buffalo hunt. After the end of the Civil War, settlers and hunters slaughtered millions of buffalo for their hides, leaving the carcasses to rot on the Plains. As one Army officer put it, “Every buffalo dead is an Indian gone.” By the late 1870s, the vast herds that had sustained various tribes had all but disappeared.

The Boarding Schools

Perceiving that permanent change within the tribes must come from the young, the government established an education policy that took the tribal sons and daughters from their homes and sent them to special boarding schools.

The federally funded schools were operated by reformers, religious orders, government appointees, general do-gooders, and army o fficers. Some of the schools were as close as Pawhuska, Indian Territory, now Oklahoma, but others ranged as far afield as Hanover, New Hampshire, and Perris, California. The students were forced to cut their hair and wear white man’s clothes. They were forbidden to speak their native language, sing their songs, practice their religion or traditions, or maintain contact with their families. Violations were answered with beatings. Moccasins were replaced with lace-up shoes, and roaches and scalp locks by felt hats.

Students learned English, mathematics, penmanship, and a history far removed from that of their tribes. The boys dressed in military-style uniforms and were taught agricultural skills; girls were educated in the arts of housekeeping, sewing, and cooking. The government considered it especially important to educate the girls in the new ways. One o fficial noted, “It is the women who cling most tenaciously to heathen rites and superstitions, and perpetuate them by their instructions to the children.”

The first of the federally funded, o - reservation Indian schools was in the central Pennsylvania town of Carlisle. Built in 1878 as the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, it was designed by Army offi cer Richard Pratt along the lines of a school he had deveoped for an Indian prison. He also adopted the motto, “Kill the Indian; Save the Man.” The school functioned until 1918, eventually taking in 1,000 children a year, with the express purpose, as the administrators put it, of cleansing their “savage nature.”

As Norman E. Matteoni writes in his 2015 book Prairie Man, “Discipline was constant. Punishment, abuse, and illness were frequent.” Ultimately, the school turned out graduates who had no viable place in either the white or the Indian world.

Many children died—of influenza, tuberculosis, brutality, and depression. In August 2017, a staff of Army gravediggers began the exhumation on the old school grounds of some 200 Indian children from more than 36 tribes, on whose tombstones— those that were not simply marked “Unknown”—were carved their whimsically assigned Anglo names. Three boys who had entered the school in 1881—Little Chief, 14; Horse, 11; and Little Plume, 9—were buried as Dickens Nor, Horace Washington, and Hayes Vanderbilt Friday. Their remains, along with those of their classmates who could be identified, have recently been returned to their tribal homelands.

The Carlisle school served as the model for dozens of institutions across the country, some of which functioned well into the 1900s. So popular was the concept of cultural assimilation for the native young that the schools spread across Canada as well.

Not until the passage of the Indian Child Welfare Act in 1978 did parents acquire the legal right to refuse to send their children to off-reservation schools. Since then, most of the boarding schools have closed.

In a sense, the Indian schools achieved their goal. Try though the students’ parents and grandparents might to preserve a vestige of the old ways, their efforts were lost on a new generation of young people who had no use for them and who often came to look upon their families and tribal traditions with disdain. The customs that had bound the tribes together were almost lost.

The Allotments

Despite the promises of the Office of Indian Affairs, the borders of the lands allocated to the Indians were soon overrun by the relentless westward progress of the white population. The phrase found in a seemingly endless string of treaties, guaranteeing the Indians their land “as long as the grass grows and the water flows,” had long since been reduced to a punchline. As one Osage headman observed, “They just keep coming like ants.”

The federal government wanted to provide cheap land to American settlers, while maintaining control over the various tribes whom it had already displaced at least once—and in some instances, multiple times. The Osage, for example, who had been removed from Missouri in 1825 and settled on a small expanse of southern Kansas, were moved again—this time to Indian Territory—shortly after the Civil War, after government surveyors had carved up their lands into parcels to sell to white homesteaders at $1.25 per acre.

During the administration of Grover Cleveland, officials hit upon what they viewed as the perfect solution: individual land allotments to the Indians. In 1887, Congress passed the Dawes Act, otherwise known as the General Allotment Act. Rather than allow the land to be held by the tribe at large, the law assigned 160 acres to each family, with single Indians 18 or older receiving 80 acres apiece. The federal government would hold the title to the land for 25 years, after which time it would pass to the individuals and families. The landholders would then be offered citizenship, provided they had “adopted the habits of civilized life.”

The respective tribes were ordered to sell to the government all the land that did not fall within the specified allotments, to be made available to homesteaders. The proceeds were to be held in trust by the government, ostensibly to be used for tribal supplies.

By assigning plots to individuals and families rather than the tribes, the government weakened the sense of community and tribal unity. And it radically reduced the amount of land originally given the tribes, making a huge portion of it available for white settlement. Prior to the allotments, the Indian reservations were spread over 138 million acres; after the system was enacted, the amount of land held by Indians had been reduced by two-thirds.

Some tribes resisted. These included the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Seminole, Creek, Osage, and factions of the Otoe-Missouria. Some tribal members harried the government surveyors, destroying their survey markers and threatening them. Others simply begged the government for compassion.

In the spring of 1895, a delegation of Otoe-Missouria visited the US capital and met with Commissioner of Indian Aairs Thomas P. Smith. The tribe’s spokesman, Little Turtle, pleaded eloquently with him not to divide their lands, but his words had no effect; Smith peremptorily dismissed the delegation, assuring them that the allotment system would be good for the tribe.

A few in Congress raised their voices in opposition to the allotments. Sen. Henry M. Teller of Colorado was outspoken in stating: “The provisions for the apparent benefit of the Indians are but the pretext to get at his lands and occupy them. … If this were done in the name of Greed, it would be bad enough; but to do it in the name of Humanity … is infinitely worse.” Other public figures, however, were not so circumspect. Theodore Roosevelt opposed any Indian who refused his allotment: “Let him, like these whites who will not work, perish from the face of the Earth which he cumbers.”

“We cannot look back and live in lodges as we used to live. We must hold the plow and turn the ground. … We do not kick about that. We have got to work for our living. That is all right. But let us hold our land as it is now, I beg you. … We can live like white men without cutting up the land.” -Little Turtle, an Otoe-Missouria spokesman who traveled to Washington

Officials withheld trade goods and threatened to assign the recalcitrant ones the least desirable, most unproductive of the allotted lands. One by one, all the tribes—with the temporary exception of the Osage—succumbed to government pressure and accepted the allotments.

Later, it was discovered that corrupt government offi cials had conspired with business interests to steal some of the allotted lands from the Indians.

The government wasted no time in opening the newly available lands to settlement and development. Railroad companies harvested the forests for ties and transected the countryside.

At noon on September 16, 1893, the firing of a gun flagged the start of the biggest land rush in American history. President Benjamin Harrison had manipulated the Cherokee into selling land for about $1.40 an acre. Some 100,000 would-be settlers, described by Grann as a “ragged, dirty, desperate mass of humanity” stampeded to claim 42,000 parcels on more than 7 million acres in northern Oklahoma Territory.

Other land runs would soon follow. By 1911, posters were being widely distributed advertising “Indian Land for Sale: Cheap Lands in the West,” for irrigation, grazing, and dry farming. “Get a Home of Your Own,” the ads read, with “Easy Payments” and “Possession within Thirty Days.” Of the 12 states listed, the second-largest number of available acres—34,664 at $19.14 per acre—were in Oklahoma. South Dakota offered more than 120,000 acres. In the center of each poster was a photograph of an old Indian, dressed in full regalia, with two feathers in his hair.

An Osage Windfall

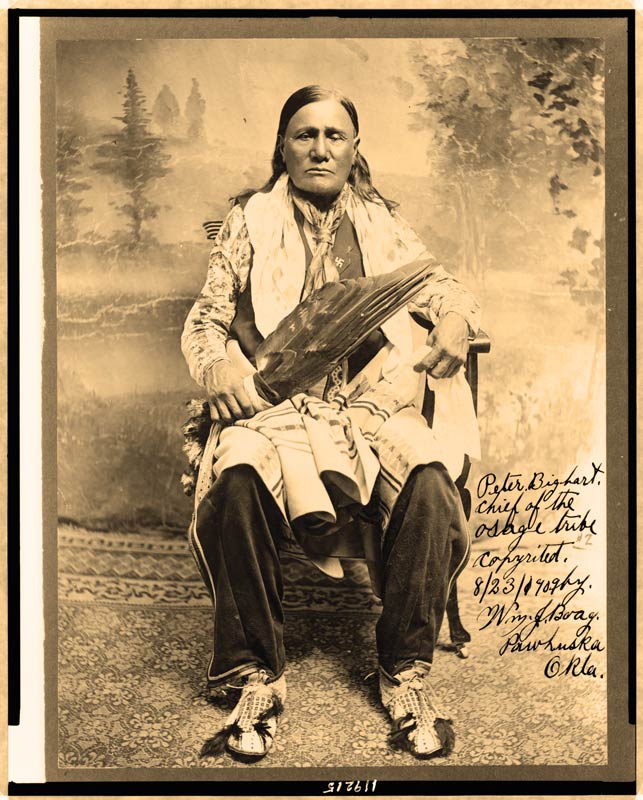

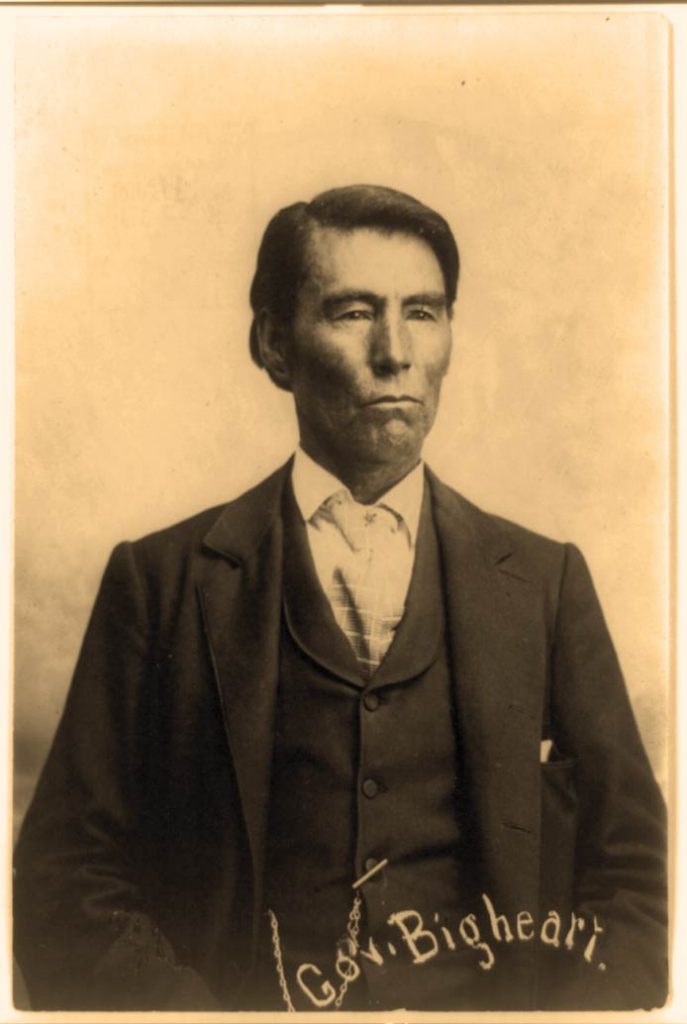

While most of the other tribes struggled for survival—both culturally and literally —during the post-allotment period, the Osage became the recipients of one of the most extraordinary windfalls in US history, through the brilliant machinations of their chief. A century ago, in his massive History of Oklahoma, James Bradfield Thoburn described Chief James Bigheart, “of all the characters in the history of the Osage tribe, undoubtedly the greatest, so far as individual influence and forcefulness in politics and all economic measures aecting the tribe are concerned.”

Hyperbole aside, Chief Bigheart was indeed a remarkable man. He was among those who organized the profitable leasing of Osage lands, with its profuse bluestem grass, for grazing. He reportedly spoke seven languages, including French and Latin, and was a brilliant negotiator, as the US government discovered.

Bigheart was able to delay for years the allotment of land to individual Osage tribal members in Oklahoma by repeatedly postponing, investigating the tribal rolls, and other obfuscating strategies. Finally, in 1904, he sent a savvy young half-Osage and all-business lawyer named John Palmer to Washington to finalize negotiations. Between the two, they persuaded the government to increase the 2,229 allotments from 160 to 657 acres each, and— most significantly—to agree that “the oil, gas, coal, or other minerals covered by the lands … are hereby reserved to the Osage Tribe.” This automatically gave each Osage tribal member a “headright”—a personal interest in the tribal trust fund that accrued from the lease or sale of tribal oil, gas, and mineral rights. Individual tribal members could not sell their headrights, but they were legally empowered to lease or sell the surface rights.

Bigheart had known that the land on which the tribe had been placed held an extraordinary secret. More than 10 years earlier, an Osage had found oil on his property, and by the time the government signed the agreement with the tribe, a number of small wells were in operation.

Tribal members soon began leasing allotment land to a growing horde of white wildcatters whose tall, wooden scaffolds sprang up across Osage land in everincreasing numbers. The same year that the tribe solidified its agreement with the government, a pipeline was run to the Standard Oil Refinery in Kansas, and within three years, what was commonly being referred to as the Osage “underground reservation” had pumped out more than 5 million barrels.

This was only the beginning. Public lease auctions commenced in 1916, as private railroad cars deposited their wealthy owners in the booming town of Pawhuska. Here, in the shade of what came to be called the Million Dollar Elm, they bid fabulous amounts for the right to drill on Osage land. One bidder paid nearly $2 million for a single 160-acre tract. By 1930, some 319 million barrels of oil—Oklahoma crude— had been taken from beneath the surface of Osage County, Oklahoma.

The money poured in, and the Osage Nation became the wealthiest per capita population in the world. Indians who had been driven from their ancestral homeland and relegated to an existence dependent on the largesse of their conquerors were now living in large, expensive homes and riding in chaueured limousines. According to the Oklahoma Historical Society, in 1926, an Osage family of five was earning an average of $65,000 a year, the equivalent of nearly $900,000 in today’s currency. The tribe that once loomed over early Missouri as the most feared of all the region’s tribes had become the authors of one of the most stunning financial success stories in American history.

There was a dark side to the Osage saga. Local white businessmen, resentful of their Indian neighbors’ good fortune, radically overcharged them for everything, including cars, household goods, and funerals. And the US government—unwilling to let the tribe determine its own financial future—dictated that every full-blooded Osage with a headright was incompetent and assigned each a white guardian whose function was to allocate the amount the Osage was allowed to spend. This provided an unparalleled and generally unchallenged opportunity for swindling and outright theft, as countless millions of dollars were siphoned from the Osage.

Worse yet, in the early 1920s, a conspiracy was hatched by whites in Osage County—landowners, politicians, medical professionals, and law enforcement officers—to murder key Osage residents for their headrights. Ultimately, J. Edgar Hoover and agents of his nascent Bureau of Investigation became involved, but by the time a few conspirators were convicted and sent to prison, at least two dozen men and women—Osages and a few white investigators—had been poisoned, blown up, shot, or beaten to death. The newspapers of the period referred to it as Osage County’s Reign of Terror, a chilling and accurate description.

According to various sources, dozens and perhaps hundreds more were murdered at the hands of their guardians or bogus heirs, but complicit coroners simply labeled their deaths as natural or accidental. One Osage leader referred to the guardianship period as “the blackest chapter in the history of this state.” Years would pass before the government would end the hated guardianship system.

Eventually, the flow of oil money, and the oil itself, dwindled. In 2000, the Osage Nation sued the federal government for the millions of dollars stolen from them during the oil boom. After 11 years in court, the government agreed to pay $380 million to those Osage still holding mineral rights.

Today, about half of the Osage Nation still live in Oklahoma. The tribe has been self-governing since 1906, and has had its own constitution since 2006. Where oil was once the source of the Osage Nation’s fiscal stability, the tribe now owns and operates seven casinos. Gaming revenue pays for a number of the tribe’s benefits. Over two centuries, the Osage Nation has shown a resilience that has seen them through the darkest of times, and it has emerged with a positive view of the tribe’s future.

The Otoe-Missouria

The other original tribe of Missouri did not fare so well. The Otoe-Missouria were driven from their land in 1854 and settled on a reservation on southeastern Nebraska’s Big Blue River. Here, the pattern was a familiar one. They were forced into an agrarian lifestyle and forbidden to hunt buffalo. They suffered as deliveries of food, medicine, and livestock failed to appear.

Gradually, the government sold o reservation land to white homesteaders. In 1881, the tribe was relocated to a reservation in Red Rock, Oklahoma. By the early 1920s, the Otoe-Missouria had been forced to give the federal government more than 90 percent of their reservation land; both the state and county taxed them on what little was left—a clear violation of the allotment agreements. It was just one more in a long string of broken treaties.

Most of today’s Otoe-Missouria reside in Oklahoma. They have sought to reclaim their heritage via their schools and a revival of their native language.

“Despite three hundred years of cultural upheaval and devastation,” Dickey writes, “the Otoe-Missouria people continue to honor traditions that reflect roots going back to their days on the Missouri River.” They bolster their tribal economy through gaming casinos.

According to Dickey, “They put their gaming revenue into other industries such as retail stores, loan companies, cattle, propane, oil, restaurants, and convention centers. The tribe also operates programs such as day care, Head Start, nutrition, wellness, housing, education, job training, and elder care. Like most native peoples, they remain very communal.”

Although the last full-blooded Missouria died in 1985, the tribe’s early history is preserved at the American Indian Cultural Center at Van Meter State Park, where tourists and tribal members can visit the Utz site, the largest and longest continually occupied indigenous village site in the state.

The Future

The Bureau of Indian Affairs is accurate when it states that no federally recognized tribe dwells within Missouri’s borders. Yet, these tribes survive. Most still reside in the states and on the land to which they were relegated nearly two centuries ago. A cultural awareness remains, and various native groups are now seeking to reclaim and preserve vestiges of their heritage: oral traditions, religious beliefs, language, and a history going back to a time when all things could be explained, the world seemed to turn in their favor, and they lived free in the land that is now Missouri. Anna Brown (left) and Mollie Burkhardt (right) with their mother, Lizzie. Anna was murdered and her mother likely poisoned for their headrights. Mollie survived.

Please call 1-877-570-9898, ext. 101 to order copies of Parts 1 and 2 of this series. The author would like to thank the following for their invaluable help and insights: Steve Belko, Executive Director, Missouri Humanities Council; Dr. Carol Diaz-Granados, Research Associate, Washington University Department of Anthropology; Michael Dickey, Site Administrator, Arrow Rock State Historic Site; Jim Duncan, Director (ret.), Missouri State Museum; Eric Feummeler, Administrator, Van Meter State Park; Jim Rehard, District Supervisor, Missouri Department of Natural Resources; John Shotton, Chairman, Otoe- Missouria Tribe; Georey M. Standing Bear, Chief, Osage Nation; Dr. Molly Tovar, Director, Kathryn M. Buder Center for American Indian Studies, Washington University in St. Louis.

Related Posts

The Tribes of Missouri Part 1: When the Osage & Missouria Reigned

Two groups with distinct cultures emerged from our region’s first residents to dominate this land. Worshipful and warlike on an untouched landscape, the Osage and the Missouria did more than live here. For centuries, they ruled.

The Tribes of Missouri Part 2: Things Fall Apart

At a time when the nations of Europe were competing for global control of trade and land, the New World offered the ideal opportunity to fill European coffers and expand their empires. The only problem was that someone already lived here.

Pickleball Is Taking Missouri By Storm

It took about a decade for pickleball to sweep Missouri. With more than 100 locations developed since 2010, Missouri might just have the fastest-growing pickleball community in the country.