Glades like this on Bell Mountain afford views of other named peaks in the St. Francois range. Some show Proffitt Mountain capped by Ameren’s hydroelectric reservoir.

About two years ago, I was looking for mountains to climb. I was living in California at the time but home in Missouri for a visit. I had a limited amount of time here and knew I wanted a challenging but rewarding backpacking experience. I had become accustomed to hiking in the San Gabriel Mountains where peaks range from 6,000 to more than 10,000 feet. I knew I wouldn’t encounter any peaks on that scale in the Show-Me State, but I still felt strongly that I needed to feel, at the end of the trip, like I had climbed a mountain.

After spending some time perusing the Ozark Trail Association’s phenomenal Ozark Trail Planner tool, available on its website, I found Bell Mountain in the St. Francois range. Bell Mountain offers a 12-mile loop with 1,683 feet of elevation change, respectable for the Midwest. Bell Mountain also offers something that you can’t get anywhere else in the country: the chance to see, in person, the result of more than one billion years of geologic time playing out.

I’ve never read a geologic explanation of how Missouri ended up with the sublime, puzzling little rock pile known as the St. Francois Mountains that didn’t have me scrunching up my face in confusion after a handful of sentences. My mind resists all efforts to comprehend the scale and scope of geologic time. I understand the concept of Pangea and I know that these mountains began forming 1.4 billion years ago, but after hours of reading and research I realize that I can’t trace the thread of their story from where it begins in the Precambrian Era to where they are today. So I’ve stopped trying. I know I can at least come to a cursory understanding of them in their present-day state—I can climb them.

The St. Francois range represents some of the oldest exposed rock anywhere in North America. Add to that their height relative to their much younger cousins the Appalachians (began forming 480 million years back) and the Rockies (started forming 70 million years ago), and the St. Francois range is in the running for the title of Mountain Range Emeritus. But we go to the mountains in search of splendor. We seek them out to be confronted with something that exists on a scale that makes us seem miniscule by comparison.

Climbing up the Ozark Trail section of the Bell Mountain loop is leg-busting work that’s rewarded by a sweeping view of nearby peaks and valleys from a rocky glade. You’ll encounter a handful of glades on this hike, and you’ll be thankful each time you do. Without these glades and the views they offer, the surrounding landscape would be obscured by suffocating tree cover.

Bill Bryson complained about the monotony of hiking deep in the forests along the Appalachian Trail without much to look at in his book A Walk in the Woods. I can tell you firsthand that mountain trails farther west are found wanting when it comes to shade. So the glades of the Ozark Trail represent a compromise, a Goldilocks zone. Enjoy the shade deep in the woods while you’re climbing uphill, and when you reach the top you get to see something. It’s a square deal, and my companions and I take it.

You can attribute a lot of the majesty of western ranges like the Rockies and the San Gabriels to their size. They create imposing figures and the mind understands intrinsically that these mountains are massive things, next to which you seem inconsequential. And that’s probably as close as a human mind is capable of getting to really understanding geologic time.

The St. Francois Mountains do not impose themselves on the mind in the same way that western mountains do. Instead, they tell you a story. It’s a story about time, and they are the perfect American mountains to tell it because they’ve been around for so much time. Their story is punctuated by the views of neighboring peaks and serpentine riverways running through the partially clear rocky glades. The story is illustrated by the plethora of biological diversity that thrives here.

That diversity can be attributed to 200 million years of being above sea level and unglaciated. Not being submerged or under ice for a long, uninterrupted stretch of time has allowed a freewheeling abundance of native species to develop and flourish.

In these mountains, I’m getting everything out of this hike that I wanted. I’m getting to hear the story of the St. Francois range firsthand. Bell Mountain is about to reveal a feature that can only be found hiking in ancient mountain ranges.

We reach the summit just after sundown. In the twilight, we explore the glades and look eastward at the peaks nearby. Camping on the summit of a fourteener in the Rockies would be an uncomfortable experience due to wind conditions alone. My companions and I set out tents under tree cover and make a fire near the rocky edge of the glade. A full moon rises over the valley after we’ve eaten, and the landscape is illuminated again. It’s early September, and the air is crisp with a rumor of fall.

I recline on the rocks after dinner feeling accomplished because I climbed a mountain. The fire crackles and the forest around us is humming with the sounds of insects and frogs. I climb into my sleeping bag and stare up at the trees. I still don’t understand geologic time but, I know for sure that I have seen the byproducts of it, as you can. It’s a stone’s throw away, down in the St. Francois Mountains.

If You Go

Bell Mountain is located in Iron County, in the Bell Mountain Wilderness, a part of Mark Twain National Forest. The loop trail starts at the parking lot off Route A, about 30 minutes from Ironton. Learn more about the wilderness at FS.USDA.gov/detail/mtnf/specialplaces. Visit the Ozark Trail Association website at OzarkTrail.com to find hiking information and a map. There’s an option to hike a section of the Ozark Trail in this area or take the loop back to the Route A trailhead.

Show-Me More

The St. Francois Mountains have plenty of peaks to climb and plenty of stories to tell.

Taum Sauk Mountain: Highest point in the state • 1,772 feet

Buford Mountain: Classic loop route to the second-highest peak in Missouri • 1,739 feet •

Black Mountain: One of the most prominent peaks in the state

1,502 feet

Mudlick Mountain: A mountain for people who believe it’s the journey, not the destination • 1,313 feet

Photos by Corey Woodruff

Related Posts

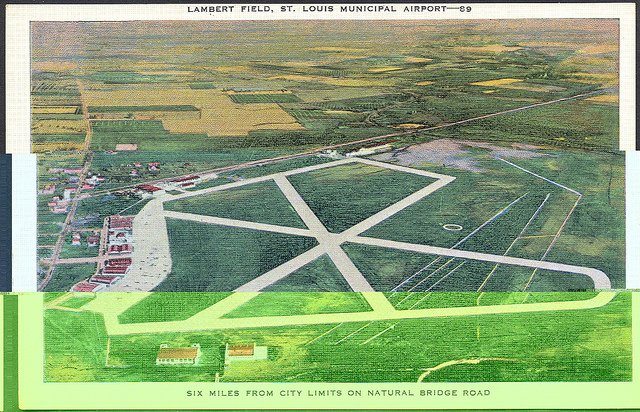

July 12, 1930

Rear Admiral Richard E. Byrd dedicated the St. Louis Flying Field as the Lambert- St. Louis Municipal Airport. With him were two St. Louisans, Captain Ashley McKiley and Ensign Thomas Mulrony, who had been with Byrd as he explored the polar regions.

The Ozark Mountain Daredevils Are Still Shining

Springfield’s good old boys got to sing and sing and sing.