Shortly after aviation took off, so did a new form of entertainment. Entertainers—many of them women—ventured onto the wings of flying planes to dazzle audiences with daring acrobatic feats. Daredevils continue to keep the tradition alive today.

Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress

By Ron Soodalter

There is a line in the wildly popular early 20th-century song, “Come Josephine, in my Flying Machine” that goes, “Balance yourself like a bird on a beam.” Beginning around the time of World War I, that is precisely what aviators and aviatrixes did for the breathtaking amusement of the crowds at America’s state and local fairs, circuses, and celebrations. In aerial shows designed to awe the masses, a pilot would go aloft in his primitive biplane, and his attractive young “associate” would climb onto and stand erect on the upper wing. She would maintain this stance, waving to the earthbound masses, as the plane went through a series of maneuvers. These stunt pioneers proudly adopted the colorful name “wing walkers.”

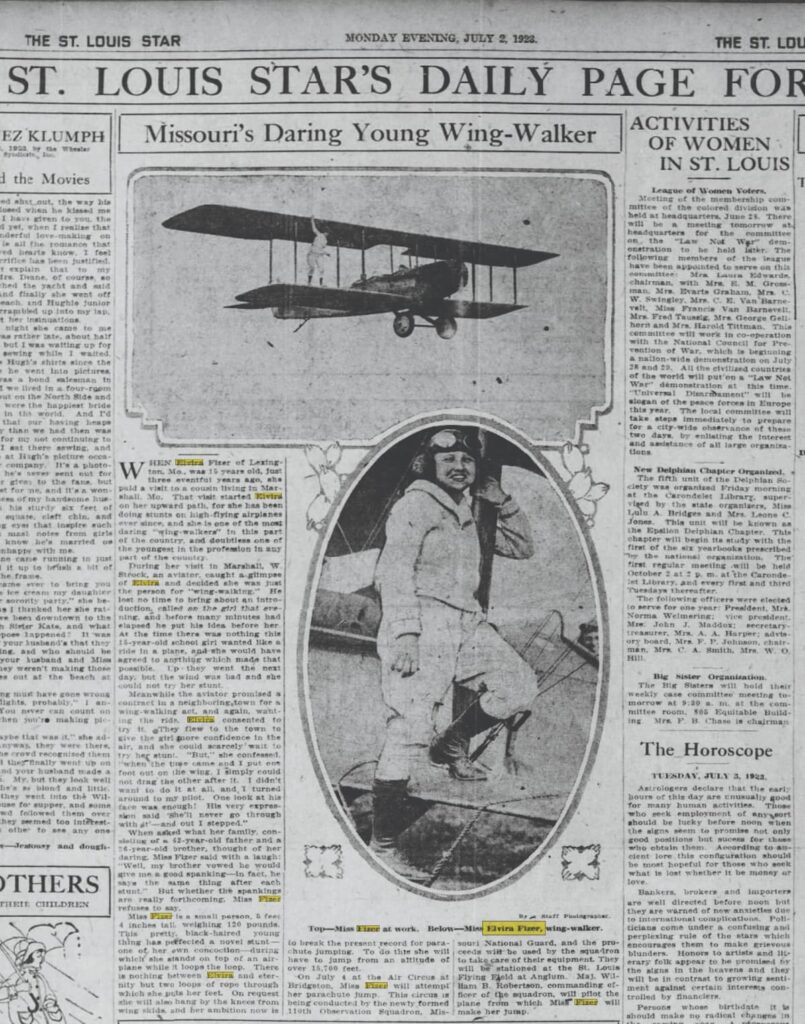

Thirsting for the thrills the colorful posters had promised, a large crowd of spectators at the 1920 Missouri State Fair looked skyward as a young girl from Lexington, Missouri, climbed confidently onto the upper wing of a biplane. Her name was Elvira Fizer, and she was among the first in what would become a century-long Missouri tradition of wing walkers.

Photo courtesy of th Library of Congress

Elvira was only 15 when she began dazzling crowds across the Midwest. A professional aviator spotted her while she was visiting a cousin in Marshall, Missouri, and instantly decided that she would make an ideal wing walker. Captivated by the idea of flying, Elvira immediately began “on-site training” on the wings of his biplane. A journalist of the period wrote, “At the time, there was nothing this 15-year-old schoolgirl wanted like a ride in a plane, and she would have agreed to anything which would make that possible.”

According to Kim Borgman, Elvira’s granddaughter who lives near Marshall, the young wing walker had a less-than-idyllic childhood. Her mother died shortly after giving birth to her, and for a time, Elvira lived with her grandparents in Arrow Rock, Missouri. Her father, a coal miner, remarried shortly after Elvira’s mother died, settled near Lexington, and fathered several more children. Eventually, he “reclaimed” Elvira, taking her to his house to help his wife with the housework. “My grandmother didn’t talk much about this time in her life,” Kim recalls, “likely because it was a painful memory.”

Seeking an escape from her dead-end existence, Elvira quickly took to wing walking. Her first experience, however, was tentative at best. “When the time came,” she later recalled, “and I put one foot out on the wing, I simply could not drag the other after it. I didn’t want to do it at all, and I turned around to my pilot. One look at his face was enough! His very expression said ‘She’ll never go through with it’—and out I stepped.”

Three years later, a reporter from the St. Louis Star interviewed Elvira at a flying circus sponsored by the Missouri National Guard. The illustrated article in the July 2, 1923, edition describes “this pretty, black-haired young thing” as standing “only five feet four inches tall and weighing 120 pounds.” The article goes on to say, “She is one of the most daring ‘wing-walkers’ in this part of the country, and doubtless one of the youngest in the profession in any part of the country.” In addition to wing walking, Elvira also learned to parachute from the plane’s wing at a time in aeronautical history when parachutes were far from fail-safe.

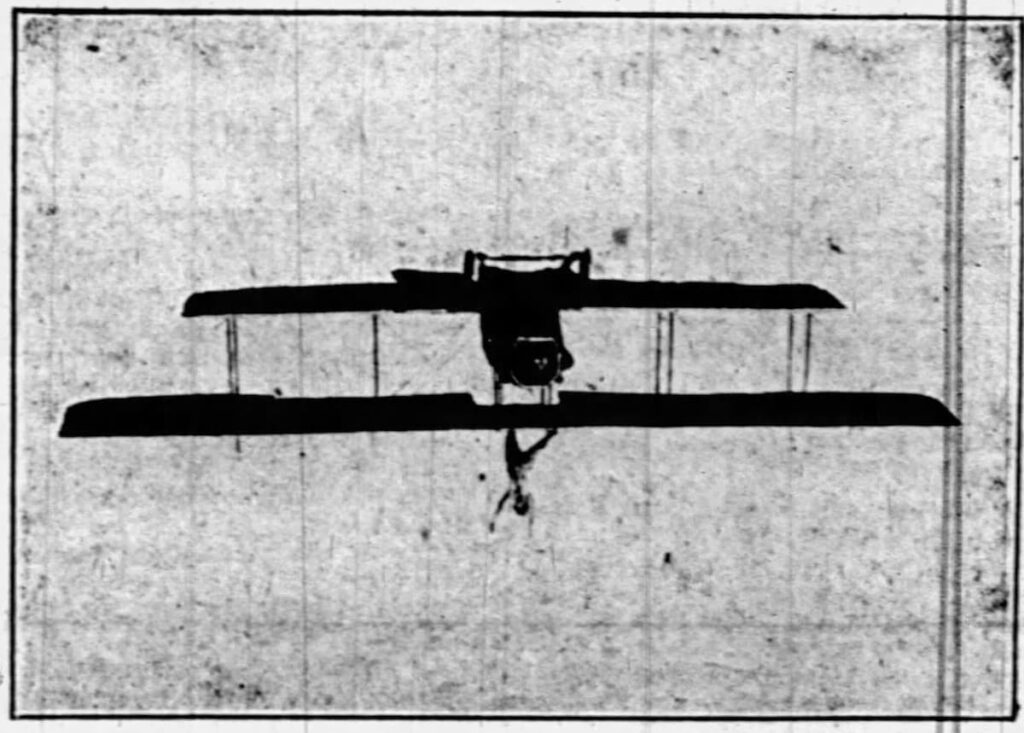

The system she used for securing herself to the wing was one of her own devising, and it was, to say the least, basic. As a journalist noted, “There is nothing between Elvira and eternity but two loops of rope through which she puts her feet.” It was while rooted in this rudimentary device that she stood erect on the wing as the plane performed 360-degree rotations—“loop-the-loops,” as they were called—and hammerheads, in which the plane would fly upward until it appeared to stall, then plummet earthward, only to recover at the last instant. The crowds loved it, and the diminutive young woman became a favorite at state and county functions.

It was another passion that finally brought gutsy young Elvira down to earth. She met and married Noble Hammer. The couple settled near Marshall and had three children together. The youngest was Kim’s father, John, who was born five months after Noble died in 1932 at the age of 34. “The loss of my grandpa was hard on Grandma,” Kim says, “and she basically wanted to block out her pain and memories and destroyed all the scrap books she had kept and cherished of her adventures.”

Photo courtesy of Public Domain

Elvira was not the only young Missourian to walk on the wing of an airplane in flight. St. Louis native Marie Meyer was a wing walker and parachutist, plus she also piloted her own plane. After purchasing an army surplus Curtis Jenny biplane in 1922, 23-year-old Marie participated in international aerial races in both St. Louis and Dayton, Ohio. She created the Marie Meyer Flying Circus, which featured a number of daring stuntmen and pilots, including a young Charles Lindbergh. In 1924, Marie married Missouri stunt pilot Charles Lee Fower. That same year, she accepted the invitation of the St. Louis Flying Club to wing walk as Charles flew between the buildings of a downtown St. Louis street. It proved to be her most perilous stunt. She later commented, “No one will ever know how close we came to ending it all that day. We did give them a show, though!” Ironically, Marie was killed in an auto accident in 1956.

Another wing walker who got through her aerial escapades unscathed was Lillian Boyer, who retired after performing her last show in Bethany, Missouri. Invited by two customers to go aloft, this Nebraska waitress climbed onto the wing on only her second flight. In addition to wing walking, she also transferred from a speeding car to a low-flying plane and parachuted from great heights. After an eight-year career beginning in 1921, she retired from barnstorming, and lived to age 88.

In addition to wing walking, aerial escapist Lillian Boyer counted among her stunts transferring from a speeding car to a low-flying plane and parachuting from great heights.

Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress

Not all wing walkers lived into their golden years; it was, and is, a perilous occupation. Although biplanes have become considerably more sophisticated with each passing decade, the danger is still present, and occasionally the result is tragic.

In early August 1951, 17-year-old Pansy “Kitty” Middleton of the Missouri Ozarks performed her first aerial stunts at her hometown airport in Willow Springs. Weeks later, she was wing walking for a crowd of over 26,000 onlookers at the Minnesota State Fair. It was only her third public performance, and all was going well until the plane failed to come out of a dive. Both Kitty and her pilot were killed.

Veteran pilot and showman Kyle Franklin of Neosho, Missouri, learned to fly a plane in 1988 at 8 years old and to wing walk at 14. The aerial incarnation of Evel Knievel, he became a legend, wowing crowds as the only daredevil to walk on the wing of a jet. Throughout his career, however, he has suffered almost unimaginable personal losses. Kyle’s grandfather was killed in a cross-country plane crash, and his father—an aerobatic legend in his own right, and Kyle’s teacher and best friend—died while performing a stunt in the skies.

In 2005, Kyle married Amanda Younkin, the daughter of the pilot who had perished in the same crash that claimed Kyle’s father. As daring as her husband, Amanda became the wing walker in Franklin’s Flying Circus and Air Show. Climbing onto the wing dressed in the pirate costume of “Scandalous Scarlet,” she would engage her pilot husband in aerial sword fights while holding on to the plane’s struts with one hand.

Photo courtesy of Franklin’s Flying Circus

Then tragedy struck yet again. In May 2011, while performing their routine over the Brownsville-South Padre International Airport in Texas, the Franklins’ plane lost power and began a rapid descent. Amanda managed to work her way from the wing to the forward seat, but the flames from the crash claimed the wing walker’s life.

After recovering from his injuries, Kyle again took to the air with his best friend, Todd Green, as his wing walker. Then in August of the same year, while standing on the wing during a performance at an airshow in Mt. Clemens, Michigan, Todd attempted to grab the skid of a circling helicopter. He missed and plummeted to his death. That same weekend, a stunt pilot crashed during an air show in Kansas City.

Understandably, Kyle was stunned. “It was a hard year for the air-show family. We’re like a tight-knit family, so when something happens, it hits us all hard.” But he continues to perform. “It’s what I love. I have no intention of getting out of the air-show business. It’s in my blood.” He has remarried, and his wife, Liz, now pilots the plane while Kyle performs on the wing.

Although not nearly as prevalent as it once was, wing walking has survived as a form of entertainment. In fact, for those who find themselves attracted to the idea of walking on a biplane wing at 3,500 feet, there is a wing walking school on the West Coast.

From the earliest days of manned flight, aerial daredevils—barnstormers, wing walkers, parachutists, and stunt pilots—have defied the odds for the amusement of the crowd, and for the personal satisfaction of successfully confronting their own mortality. Missouri’s early wing walkers were the rock stars of their day to some, and certifiable lunatics to others. But no matter how the performers were viewed, people turned out in the thousands to watch the show with bated breath.

A fearless few, like Kyle, keep the spectacle alive. But today’s technological advances, many of which have redefined the concept of leisure time and created increasingly sophisticated distractions, have all but rendered the flying circus and its death-defying performers a romantic ghost of America’s past.

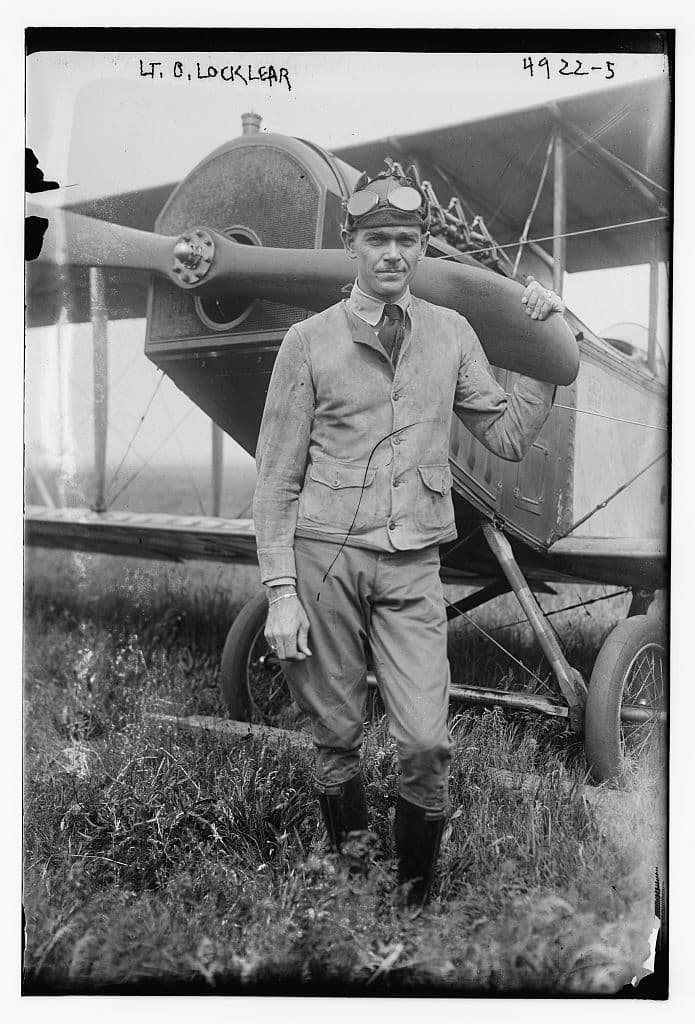

The Man Who Inspired the Spectacle

Photo courtesy of Kim Borgman

Although the first documented case of wing walking occurred in 1911, it was, in fact, popularized by a young lieutenant in the US Army Air Service—the forerunner of the modern-day Air Force—during World War I. An exceptional pilot and flight instructor, the young, handsome Texan, Ormer Locklear, enlisted too late to see combat. He did, however, have occasion to twice climb onto the fuselage of his Curtis Jenny biplane while in flight: once, to stop a radiator leak, and again, to reattach a spark plug wire.

Apparently drawn to the danger, Locklear broadened his exposure by crawling to various parts of his plane when aloft, including the wingtip. At one point, he began standing on the wing itself and culminated his derring-do by transferring from one in-flight plane to another. Court-martialed for his actions, the silver-tongued young pilot convinced his superiors that his plane-to-plane transfer should become a useful part of training. Before leaving the service at war’s end, he performed the stunt some 300 times, acquiring the sobriquet “The Human Fly.”

Locklear caught the attention of Hollywood and was tapped for some stunt work in films. In early August 1920, the Fox Film Company was shooting the last scene of The Skywayman, in which it would appear that Locklear’s flaming plane was plummeting to Earth. Fireworks were attached to the fuselage to provide the impression of fire. Locklear put his plane into a steep dive after igniting the pyrotechnics, and either blinded by the fireworks or having misjudged his altitude, he crashed. Both he and his copilot died instantly in the fiery wreck.

Ormer’s death did nothing to discourage others from performing daring stunts while aloft. In fact, state fairs saw a significant leap in attendance whenever a “flying circus” was in town. The performers were, for the most part, young women, many of whom left what they saw as their dull lives for the thrills, celebrity, and money that aerial performances could bring.

Feature image from Shutterstock

Article originally published in the March/April 2024 issue of Missouri Life.

Related Posts

Charles Lindbergh is Born: February 4, 1902

Birthday of St. Louis resident (as an adult), Charles Lindbergh who flew the Spirit of St. Louis.

Explore the Space Museum in Bonne Terre

The Bonne Terre Space Museum and Grissom Center opened 20 years ago as a tiny museum with great potential. Two decades later, museum president Earl Mullins and a group of enthusiastic volunteers have worked hard to grow the museum’s collections and inspire the next generation.

Injured German shepherd apparently survived crash

Powerful thunderstorms moved through our area on the night of May 22, 1962. As threatening weather passed, my father went outside, came back in later, and said, “I heard something, and I don’t think it was thunder.”

Missouri’s North Star

Explore nature, visit art galleries and museums, and eat plenty of pancakes in Kirksville.