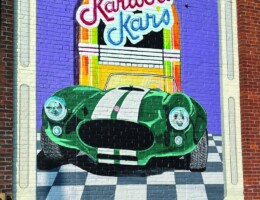

Cities and towns across Missouri are telling their stories and adding beauty through colorful murals. Discover how these murals have transformed neighborhoods, learn what it takes to create a mural, and see beautiful examples of the art form.

On your drives through Missouri, you may glimpse murals brightening the streetscapes of small towns and big cities. If those murals really capture your attention, you will slow down or even park nearby to get a closer look—and to ponder stories told large, in paint, on walls of old buildings or once-overlooked alleys.

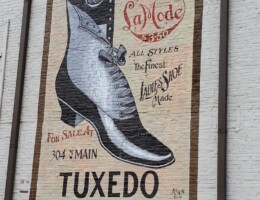

Murals tell stories of railroads or riverboats, of founders, famous people, and points of pride. They tell of beloved residents their hometowns will never forget. Whatever their stories, murals lure thousands off the highways—even off the Mississippi River—to roam revitalized artistic and business districts and learn more about communities through larger-than-life pictures.

“They really are a tourist attraction,” Elizabeth Haynes says of Cape Girardeau’s murals. Elizabeth is executive director of Old Town Cape, a Missouri Main Street nonprofit program dedicated to historic preservation and economic development in a 130-block area of the southeast Missouri riverfront city.

“We have thousands of people who come on dozens of riverboats April through October,” Elizabeth says. “They park their riverboats there, and they come and explore for the day and patronize our local businesses and view our murals.”

Completed in 2021, a postcard-style Welcome to Cape Girardeau, Missouri floodwall mural by local artist Craig Thomas beckons tourists floating past on the Mississippi. On the downtown side of the floodwall, the River Tales mural depicting Cape Girardeau history spans several blocks. Elizabeth says the block-long Missouri Wall of Fame mural often prompts comments from visitors who didn’t realize people like broadcaster Walter Cronkite or scientist George Washington Carver were Missouri natives.

Cape Girardeau isn’t the only Missouri city where murals attract visitors. More than 200 miles north along Mississippi, Hannibal history and the town’s most famous son, author Mark Twain, are celebrated through the art form.

Twenty-five murals commemorating city landmarks and well-known Twain tales, like Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn, have only been painted since 2020, says Hannibal Convention and Visitors Bureau representative Kason Bonvillian.

“Mark Twain is still our big thing, but there’s definitely a growing interest in (the murals),” Kason says, “and people really enjoy going around and seeing them.”

A Town’s Bread & Butter

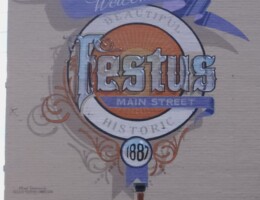

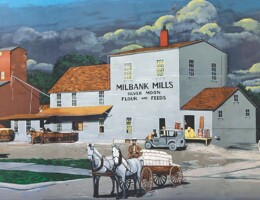

Since the 1990s, murals have helped boost economic development in the north-central Missouri town of Chillicothe, known as the “Home of Sliced Bread”—the town’s main claim to fame since the Chillicothe Baking Co. was the first to use a bread-slicing machine in 1928.

One mural there toasts that distinction. Twenty-four others depict the history of this town of about 10,000 residents.

Milwaukee Depot, for example, portrays a late 19th-century town of horse-drawn streetcars, while Webster Street View, the first to be painted, shows the street as it was in 1916.

Downtown Chillicothe was a busy place then, but some 70 years later, things had changed. About 30 years ago, Main Street Chillicothe Executive Director Tomie Walker explains, “everybody was going to shopping malls and strip malls, and a lot of rural downtown areas were becoming blighted and empty and broken.”

Tomie says that’s when Chillicothe Development Corp. members decided, “‘We can’t let our downtown dry up and blow away.” Murals to showcase city history and to beautify and bring revenue back to the Livington County seat seemed a creative solution.

Yet, according to Tomie, beginning with Webster Street View, the best thing the murals brought to town was a sense of pride.

“It gave a visual, substantial, concrete thing for people to get behind,” she says of that first mural. “It was kind of a rallying point for everyone.”

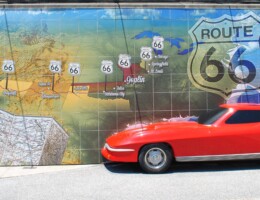

For passersby, murals are also points of interest in places like the Crawford County town of Cuba — dubbed the Route 66 Mural City since muralist Ray Harvey began painting them there in 2006.

Murals as Mirrors

Murals along the Mother Road also tell part of the Jasper County story on that historic route. Yet Joplin Arts District founder Linda Teeter, a photographer and art gallery owner herself, stays busy writing grants to fund more murals there, ones that she hopes will tell other significant stories.

Linda says she hopes the murals along the 56 blocks of the Joplin Arts District create a friendly atmosphere in which people can see themselves. “They see something on a wall that speaks to them, that is also them.”

For example, the Black History and Performing Arts mural, sponsored by the arts district and the Langston Hughes Cultural Historic Society and completed by Kansas City muralist Alexander Austin in 2022, portrays not only the Joplin-born poet and playwright but a dozen other African-American artists with ties to the city.

“These are performers that came and visited us — Ella Fitzgerald, Sammy Davis Jr.,” Linda says.

Symbols on murals speak to visitors who stop to take a look, but their meaning is even clearer to locals.

On Welcome to Joplin Arts District, painted in 2020 by Joplin and Springfield muralists Andrew Batcheller and Linda Passeri, poppies symbolize the Joplin Memorial Hall and the city’s veterans, while a half-moon represents the Dream Theatre Troupe. Linda Teeter explains that a bending lamp is a nod to the old-fashioned street lamps found in the former mining town.

Likewise, when longtime resident and artist Linda Passeri painted purple coneflowers two stories tall on a turn-of-the-century brick building in Springfield’s Commercial Street district, those native flowers symbolized revitalization along the historic street.

“Those coneflowers were really the representations on C-Street for growth, and how every day brings some new growth,” she says.

A Ticket To Remember

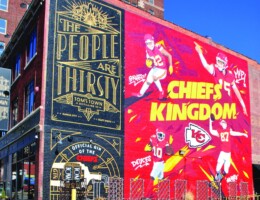

While there’s no mistaking the triumphant message of the bright red Chiefs Kingdom mural on the side of the Tom’s Town Distilling Co. building in Kansas City’s Crossroads District, passersby less than a mile east often wonder about the Wonka Golden Ticket in a Bunker Center for the Arts mural “in loving memory of Jeremy A. Bena.”

The camo-capped man, whose smiling eyes beam from the vibrant painting, was a Kansas City native, a graduate of the Kansas City Art Institute, and the first studio artist at the center that was founded in 2015, gallery director Tj Templeton says.

“It was such a loss,” Tj says of Jeremy’s 2022 death. “Everybody who knew him loved the guy.”

Jeremy also painted murals, including one on the front of the arts center, so after he died, friends and family created the one on the side of the center in his memory.

And the Willy Wonka ticket from the Roald Dahl story Charlie and the Chocolate Factory? “Jeremy used to say he wanted his artwork to make people feel like Charlie Bucket, to take them on an adventure,” Tj says.

In Chillicothe, another fondly remembered muralist is memorialized in Chillicothe Arts, the last of the murals Kelly Poling painted there while battling cancer in 2018.

Tomie Walker says that friends insisted Kelly paint himself into the scene. The artist died later that year.

“If you see the mural, there’s a ladder, and there’s a guy standing on it painting,” she says. “And that’s Kelly.”

Art for Everyone

The joy of creating such publicly visible art is what keeps muralists climbing ladders to create their massive works. Ray Harvey estimates he has painted almost 600 murals since the 1990s. One of his favorite compliments came from a Hannibal woman who sent him a cell phone photo of his Mark Twain Zephyr mural.

Explaining that she admired the mural every day at a stoplight, she took the photo through her windshield.

“My art brings art to the people where they are,” Ray says. “They don’t have to go to an enclosed facility, pay a fee, and go in to see an exhibit.”

Linda Passeri agrees. The longtime muralist is proud that her murals are accessible to everyone who can see them. “To me, a community that brings art into the public makes art equal to all.”

Behind the Brush Muralists share the secrets to creating super-sized art.

Growing up in North St. Louis and crossing the Mississippi River on Sunday drives with his family, Ray Harvey always admired the giant, colorful Piasa bird painted on the limestone bluffs near Alton, Illinois.

He loved being able to see the monstrous creature of Native American mythology from the road.

“I would think to myself, ‘What would it be like to paint something so big, so high, seen by so many people so far away?’”

Now, after painting close to 600 murals—most in Missouri—the 65-year-old Franklin County artist can answer those questions.

So can other Missouri artists whose canvases include buildings, tunnels, overpasses, underpasses, fences and retaining walls. But unlike artists working on a smaller scale, they also design their work from that Sunday driver or sidewalk pedestrian’s perspective — and use construction tools as they literally take their art to new heights.

“You have to use different tools, you have to think large, you don’t noodle little bitty details — that’s worthless,” says Ray, an illustrator, creative director and commercial artist before he began painting murals more than 30 years ago.

The American flag mural he painted last year in Concordia is 100 feet wide. And the eyes gazing steadily from the familiar face of author Mark Twain pictured on Hannibal’s four-and-a-half-story City Hall? Three feet tall, says Ray, who painted that mural, too.

Working eye-level on oversized pictures to be seen from far away can be a challenge for muralists.

When Linda Passeri painted towering purple coneflowers on a historic two-story brick building on Commercial Street in Springfield two years ago, her sister, glass artist Mary Passeri, used her cell phone to provide a passerby’s view of the progress.

“She would stand down on the street and take a photo, and she would text it up to me, and I could kind of get an idea of how it looked from the street,” says Linda, also a ceramic artist, graphic designer and painter working on smaller canvases.

Painting a scene may take a muralist a few days or a week or two, but planning takes much longer, she adds.

They may start with simple pencil and paper sketches or computer tablet designs, yet from there muralists use computer software to scale up designs for the spaces they’ve been given. And, often commissioned by cities, civic groups and businesses, they can’t change their minds as they go.

“You have to be more in a production mindset than in a creative mindset because at that point, by the time you get to the wall, all your decisions have to be made,” Linda says.

Getting designs onto walls is a task in itself.

In the old days, Ray says he sometimes lugged a clumsy opaque projector to work sites. Today, a Bluetooth projector that fits in his pocket casts designs onto multi-story buildings so that he can trace them as he prepares to paint.

“That’s the only foolproof way to get your image accurately on the wall,” he says.

When they’re ready to paint, both Ray and Linda say they use high-quality acrylic primers and paints formulated to withstand the elements, yet there are exceptions. To paint the C-Street coneflowers, Linda used mineral paint imported from Italy to meet National Register of Historic Places stipulations for building renovations.

Yet they also keep common spray guns and cans of high-quality graffiti paint close by, along with the types of brushes most folks keep in garages or tool sheds —and even though their paintings are larger than life, that doesn’t mean the brushes they use are big, too.

“People would find it surprising that for a one-hundred-foot mural, I use a two-inch brush,” Ray says.

Muralists rise to their unique artistic occasion with other construction tools, too—specifically, ladders, lifts and scaffolds.

Linda admits she’s “not a fan of heights.”

“When you have your lift extended all the way up and there’s a little bit of a breeze, it can be a little tense,” Linda says, recalling the Welcome to Joplin Arts District mural she painted with Joplin muralist Andrew Batchelor in 2020. “But you just gotta try to forget about it and work on your painting.”

Meanwhile, a photo on Ray’s website shows him standing atop the 55-foot Hannibal City Hall building.

“Yeah, it can be dangerous,” Ray says of the work. “But in all the years I’ve painted, I’ve only fallen once—and that was when I fell off the lowest rung of the ladder. Twelve inches off the ground.”

Then there’s the weather. For summer projects, muralists try to get most of their work done before the day heats up.

Ray was at the original Concordian newspaper building by dawn this week to work on a new mural, Freedom of the Press. Planning a late July start to a Welcome to Woodland Heights mural for an underpass in her neighborhood, Linda says she’ll get there early each morning.

Once on site, the 60-year-old Springfieldian says she enjoys the work. It reminds her of her days as a sign painter more than 30 years ago, when signs were still hand-painted by artists, not designed on computers, she says.

The fact that her murals, like hand-painted signs, may one day go by the wayside doesn’t concern her, though.

“Any kind of public art has to be considered temporary,” Linda says. “And some artists, they’re not good with that.

“I’m fine with it. It’s there for as long as it’s there, and then time to move on.”

Related Posts

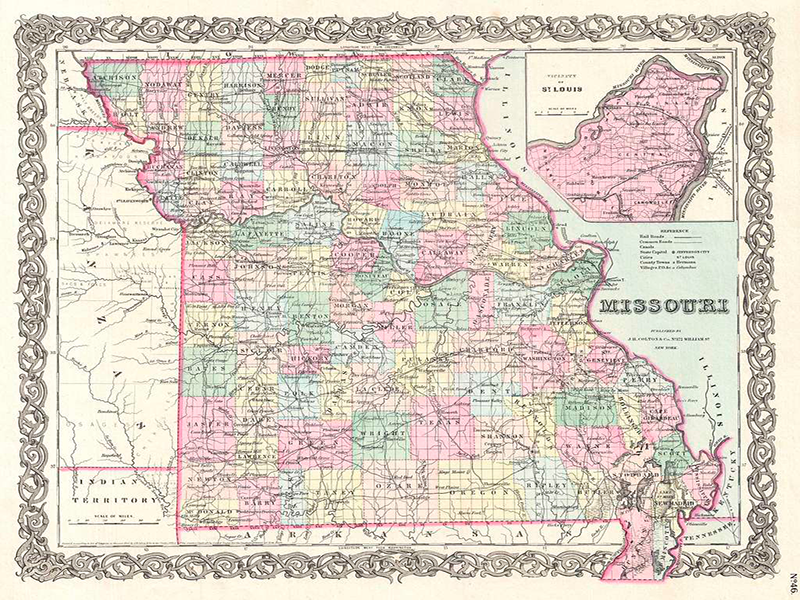

Missouri Counties Formed

On January 2, 1833, new Missouri counties, including Carroll, Clinton, Greene, and Lewis, were formed on this date.

108 Missouri Wineries

On December 11, 2012, state officials announced that there were now one hundred and eight commercial wineries operating in Missouri.

Revitalizing Missouri Downtowns

Here’s how Missourians are working together to revitalize downtowns across the state.