Writer Matt Crossman fills us in on his first foray into deer hunting. He finds that the harvesting of an actual deer is not the most important part of deer hunting. And you will find out why he thinks of Raisinettes differently now.

By Matt Crossman

Story and Photos by Matt Crossman

I learned to hunt deer from my friends Aaron and Nate Blough, identical twins from O’Fallon. The way I tell them apart is that Aaron is the good-looking one and Nate is the handsome one … or shoot, maybe it’s the other way around. I can never remember.

They own property between De Soto and Potosi, near Washington State Park, and before hunting season officially began, we spent an October day completing what I called “hunting practice.” On that beautiful fall day, I helped clear out brush and cut down small trees near each stand to give us better views. “The stands are all pretty shaggy this year, so we’re spending more time cleaning them up,” Aaron said. “It helps a lot. There’s nothing worse than being out there, and you know there’s a deer. And you don’t have a shot.”

Well, there is one thing worse, and that’s knowing there’s a deer, having a shot, but being unprepared to take it, which I learned the hard way.

Snow crunched under my feet. Sleet pelted my face and stung my eyes. I unzipped the deer hunting blind, climbed inside, and found protection, though not warmth. I set down my borrowed rifle and peered out the shooting holes. Covered in snow and cloaked in darkness, the field lacked definition, like a shimmering pond imperfectly reflecting the trees around it. I waited for the sun’s light to clear things up.

The dull gray world in front of me slowly evolved to crisp black and white. It was as if I put on my reading glasses and a book’s foggy ink became letters and words. Branches acquired definition, individual trees stood out among the forest, and unknown shapes revealed themselves as stumps.

As the visual world came into focus, so did the audial world. I thought of what my friend Tim said when I asked him what he loved about hunting. “It’s the sound of the woods waking up,” he said. “The birds, the squirrels—you can hear everything.”

On this morning—a Tuesday in November, amid an uncommonly early winter storm in Washington County—I would add the sound of ice pinging off the roof of the blind, with the occasional cymbal crash when large pieces fell off the tree above me.

Once there was enough light to take pictures, I stuck my phone out a viewing hole to snap a few. I looked away from the field to set my phone down. When I looked toward the field again, a doe, broad-shouldered and majestic, stood stock still in the middle of a trail 40 yards from me. I can only guess she came from the woods to the left, but how she got there without me seeing or hearing her was a mystery.

She stood broadside, a hunter’s dream. I slowly moved to get my rifle. She saw that, jerked her head toward me as if to say, “Not today,” and bounded directly away before making a sharp left turn into the woods. And thus ended my best chance to get a deer on my first-ever hunting trip.

I could not have picked a better place to start my hunting career, both in general (Missouri) and specifically (Washington County). With roughly 1.6 million deer, Missouri’s deer population ranks in the top 10 among all states. With 20 to 35 deer per square mile in most counties, the animals are spread fairly evenly across the state, says Kevyn Wiskirchen, a private-lands deer biologist with the Missouri Department of Conservation. In the last decade or so, Missouri conservation policies have allowed deer populations in the state’s southern third, which is marked by heavily wooded areas such as the Ozarks, to increase and catch up to the rest of Missouri.

Deer are “habitat generalists,” Kevyn says, meaning they can live in just about any environment in Missouri, though they tend to like some areas better than others. They particularly thrive in fragmented landscapes, where woods,fields, and farms butt up against each other.

“If you think about the great plains of Nebraska and Kansas and things like that, they’ve got white-tailed deer—and they’re big whitetails—but there’s just not that many of them,” Kevyn says.

As a species, deer eat at least 600 types of plants and perhaps more that researchers don’t yet know about. “The soil here is able to produce a lot of biomass and a lot of highly nutritious forage for deer,” Kevyn says.

While I had never hunted before now, I’ve been around hunters my whole life. I grew up in Michigan, where some schools close on opening day of rifle season. My first job was at a small daily newspaper. We ran photos of harvested deer every opening day. When I arrived at the office early that morning, the parking lot would already be packed with hunters eager to have their photos make it into that day’s paper.

The vast majority of hunters learn the sport from their dads. Tim sent me a picture of himself and his son in their deer blind near Troy, with the lone deer they saw that day far in the distance. Another friend showed me a picture of his daughter, smiling broadly with her first deer that she harvested near Hannibal. When I told him of my missed chances, he told me she was available to serve as a hunting coach or consultant.

Maybe some years he remembered to bring his rifle. His life with a wife and his four sons, who had been born within a six-year span, was pure chaos, and if his way of escaping was to flee the suburbs of Detroit for the Upper Peninsula of Michigan for two weeks every year, I do not judge.

In preparing this story, I learned he took my three brothers out into the woods with him. He never took me. My guess is that’s because he knew I wouldn’t shut up. He’s right! I would have asked him 10 billion questions.

Just like I did during this trip with Aaron and Nate.

My twin friends own the land with their brother, Dave, and parents, Carl and Sherry. They believe strongly that the point of having such a property is to share it. Among the friends who visit there often, the place is known simply as The Property. It was the ideal location for a newbie—abundant deer, lots of the fragmented landscapes Kevyn described, and private. By the time I arrived on the Sunday of opening weekend, the family had already gotten five deer. “There’s going to be none left!” I texted to Aaron.

“Not likely,” he responded, and my three days there proved him right.

Still, the number of deer and our success hunting them was only marginally important to the amount of joy the trip yielded. I’m not the only one who thinks hunting is fun regardless of my success. For proof, I submit that, according to stats provided by Kevyn, the average number of deer harvested in the last five years in Missouri is 290,586. Compare that with the number of hunters: 485,000. Considering many hunters get more than one, that means many, many hunters go home unsuccessful, and yet they go back again, year after year.

It’s a strange sport that so many people fail and yet remain eager to try again. I learned why at The Property. The beauty, the silence, the reverence all make an indelible, lasting impression on us. Yes, the actual process of hunting is thrilling, and it always will be, no matter how many years we return home empty handed. At The Property, I discovered the camaraderie, the laughs, and the bonding are at least as important as filling a freezer full of venison.

Aaron, Nate, and I spent downtime in the afternoon gawking at bad TV from the 1980s and the night watching worse movies, all while feasting, including venison from a deer shot by Aaron’s son.

And we laughed often, with and at each other. One morning, Nate (the handsome and/or good-looking one) offered to walk me out to a stand they call “Old Faithful.” Old Faithful earned that moniker when many hunters found success atop it. The Property is a labyrinth of hiking and ATV trails, and I did not know how to get to Old Faithful. Nate volunteered to show me where to go.

As we walked along the trail, he mumbled something about looking for tracks in the snow. As we reached a corner, he pointed to a pile of scat. “That looks fresh,” he said.

He bent over and picked up a couple pieces.

As he held the deer poop, I had the strange thought of wondering if his hands were clean. I almost asked him, and I’m glad I didn’t because even if they were clean before, they weren’t anymore. He rubbed the pieces between his fingers, as if inspecting them. Was he looking for acorns or some other nut buried in the gooiness? And if he found whatever he was looking for, what would that tell him?

These seemed like good questions. Again, I was tempted to ask, but again, I didn’t.

Then he popped the scat in his mouth and ate it.

I fell for it for roughly half a second.

Because it wasn’t scat.

It was Raisinettes, and he had planted them there an hour earlier in anticipation of pranking me.

Aaron (the handsome and/or good-looking one and definitely not the one who pretends to eat deer poop) sat with me for hours in a blind on my first day. We’ve fished in Montauk State Park and Crane Creek, camped with our kids, goose hunted, rode ATVs in Alaska, and now this.

The shadows from the trees to our right elongated across the field. The dying light turned the dead grass a muted brown—the same color as deer.

“You could miss them if you’re not looking right at them,” Aaron said. “Think how many there are around here. You don’t see that many. They’re so well camouflaged.”

The field in front of us was an ocean of knee-high grass with lanes cut into it. Wind whispered through the trees that lined the right, left, and distance. My pen scratched across my notebook.

“The ‘nothing happens’ is the best part,” I wrote, and I meant it.

I was so wrong. I’m almost embarrassed to admit it.

I only thought that because, at that peaceful moment in the outdoors, I hadn’t seen a deer yet. Then, I saw multitudes, including a pack of them one afternoon. They hovered on the far edge of my shooting range. I shot and missed.

Next came the doe that appeared from nowhere and turned broadside. But she scampered away before I lined up the shot.

My fitness watch showed my heart rate jumped from 59 beats per minute to 100 during that encounter. I had heard about the symptoms and realized I had a full-blown case of what hunters call “buck fever.”

Early on the last afternoon, I had one more chance. I arrived at a tree stand at the exact same time as a deer. If I had arrived three minutes earlier, I would have been in the tree stand and had an easy 10-yard shot. Instead, I watched her run away. Again, I was unprepared to take the shot.

And that’s okay.

There’s always next year.

Missouri Firearms Deer Hunting Seasons

Early Antlerless Portion: October 6–8 (in open counties)

Early Youth Portion: October 28–29

November Portion: November 11–21

Firearms CWD* Portion: November 22–26 (in open counties)

Late Youth Portion: November 24–26

Late Antlerless Portion: December 2–10 (in open counties)

Firearms Alternative Methods Portion: December 23–January 2, 2024

*Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD) is a fatal neurological disorder that affects deer, elk, and moose. The Missouri Department of Conservation added hunting opportunities in 2023 to better control the deer population and thus reduce the incidence of the disease. Consult the MDC.mo.gov website to determine if these new seasons are applicable in your county.

Read how Missouri communities roll out the red carpet for deer hunters here.

Discover more about 19 Conservation Areas in Missouri here.

Article originally published in the October 2023 issue of Missouri Life

Related Posts

Hunter Forced to Watch Bambi

On December 17, 2018, a hunter from Barton County was sentenced to watch Disney’s Bambi repeatedly during his year-long prison sentence after being convicted of killing hundreds of deer illegally.

Striking a balance: Healthy herds and deer management

The Missouri Department of Conservation (MDC) invites landowners and others interested in managing deer on their properties to learn about its Deer Management Assistance Program.

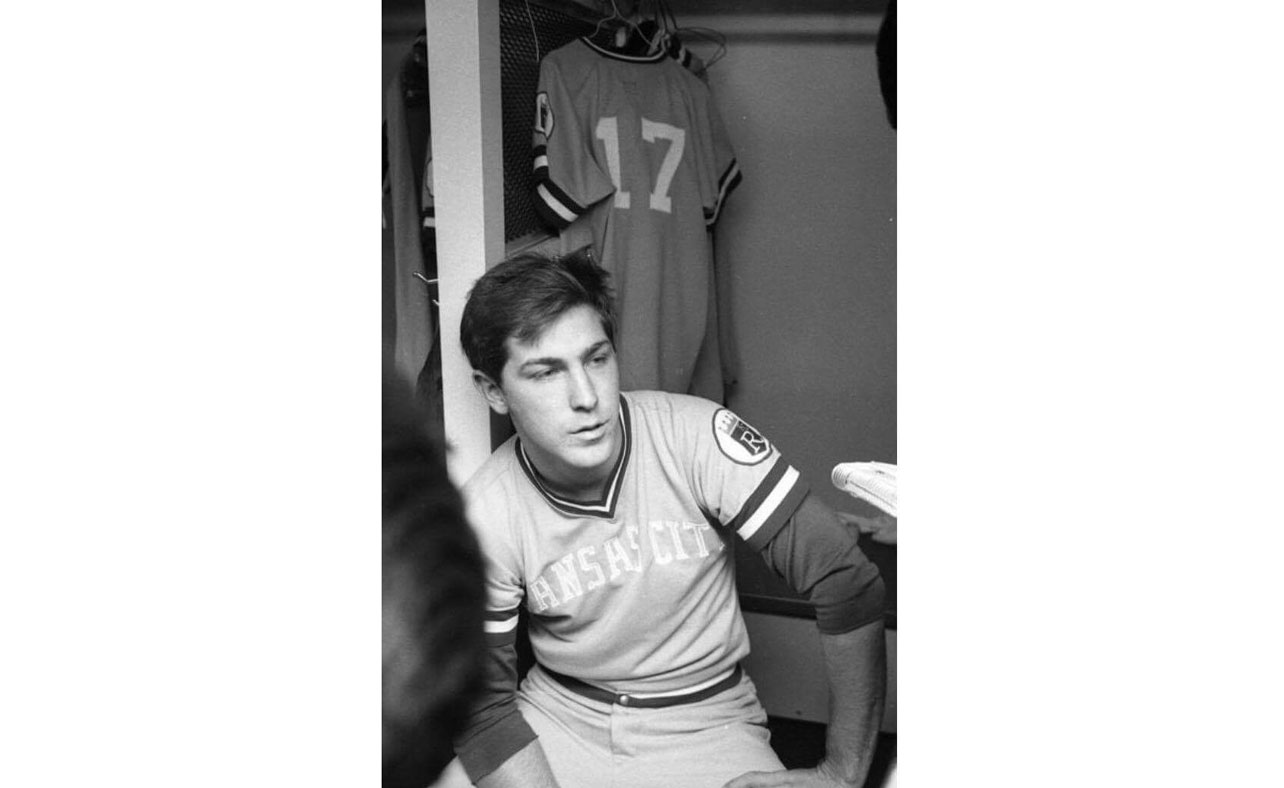

Mark Littell Shares His Wildest Stories

Country Boy is Mark’s second book, following his 2016 memoir, On the Eighth Day, God Made Baseball. Mark, who used to enter games to John Denver’s “Thank God I’m a Country Boy,” describes his latest work as a coming-of-age nonfiction story about how his character formed while growing up in Missouri.