Originally published in April 2017.

On Christmas Eve, 1895, a shooting occurred in a North St. Louis saloon that was destined to find a prominent—and permanent—place in American oral tradition. The participants were two black men, a levee hand named William “Billy” Lyons and a part-time carriage driver and full-time pimp named Lee Shelton. In the course of an argument, Billy snatched Lee’s Stetson hat from his head, whereupon Lee first struck and then shot him. Billy died of his wound shortly thereafter, and Lee was sentenced to a twenty-five-year prison term. These are the bare bones of the case, upon which have been piled countless folk tales, legends, and outright lies, ultimately giving rise to what has become one of the most popular American murder ballads as well as one of the most widely adapted song in our national history.

“Stagger Lee,” alternately known as “Stagolee” or “Stackalee,” has been reinvented innumerable times as a work chant, field holler, blues, rag, jazz, rock, and folk song. It surfaced as the theme of a major work, Staggerlee Wonders by noted poet James Baldwin, and is the subject of the book Stagolee Shot Billy by Cecil Brown.

It is virtually impossible to predict what people or events will be caught up in the myth-making machine and what will simply fall by the way. Lee Shelton himself, armed with a pistol and buoyed by drink on that Christmas night more than 120 years ago, certainly had no inkling that his rash act of violence would elevate him to the pantheon of mythical Americans. And looking at the history of the man objectively, there is no reason to anticipate that it would.

Somewhere in his youth, Lee Shelton had acquired the nickname “Stack” Lee, presumably after a steamboat—the Stack Lee which was then plying the Mississippi River. Physically, he was unprepossessing. At five-foot-seven, he was a relatively small man with a crossed left eye. According to the prison record, he had a face and torso that boasted several scars. He owned one of the tenderloin’s more notorious nightspots, the Modern Horseshoe Club, and presumably used his job as carriage driver to direct white visitors emerging from Canal Street’s Southern Railroad Station to his nightclub, the local bordellos, or directly to girls whose activities he personally oversaw.

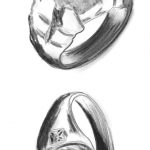

Lee belonged to a group of pimps known as macks. They were conspicuous for their strutting style and their flashy clothes. According to Cecil Brown, on the night Lee killed Billy Lyons, he wore a black dress coat, high-collar embroidered yellow shirt, elaborately patterned red velvet vest, and gray striped slacks. Dove-gray spats covered the tops of his St. Louis flats low-heeled shoes, with long, pointed, upswept toes, on each of which was a small mirror, designed to catch the light. He wore gold rings on his fingers and carried a gold-headed cane. Crowning it all was an expensive highroller, white Stetson, its hatband adorned with an embroidered image of his favorite girl, Lillie.

There was no lack of carnal opportunity in Lee Shelton’s part of town. It was a notorious red-light district, known as Deep Morgan. A bastion of blues and ragtime music, Deep Morgan was also a neighborhood in which gambling flourished and prostitution was rife. There, the infamous brothel, colloquially known as the Bucket of Blood, could operate without fear of civic interference. It was to Lower Morgan Street that the urban white people from the city’s more upscale sections would “go slumming,” then to their respectable homes before daylight caught them out.

With the growing flood of immigration of poor Southern blacks in the decades following the Civil War, the black sections of town quickly began to overflo . Slums were the natural result, and by the 1890s, 85 percent of the city’s black population occupied only 2 percent of its space. Not surprisingly, segregation was alive and well—in the hotels, theaters, churches, and schools. Within a few years, the city would pass a referendum banning black people from living on blocks that were minimally 75 percent white.

For such men as Stack Lee Shelton, however, business was booming. In addition to his holdings in Deep Morgan, Lee occupied an impressive brick house at 911 North Twelfth Street, situated in a more upscale neighborhood. This did not impede him from building “cribs” in back of his house, where some of his girls conducted business under his watchful eye.

Concurrent to following the demands of his profession, Lee was also the president of a social body known as the Four Hundred Club. In addition to being a “sporting” circle, it strongly supported the city’s Democratic Party. The Four Hundred Club presented itself in the strictest of moral tones and professed to advance “the moral and physical culture of young colored men” and to eschew all acts of violence. Following Lee’s shooting of Billy Lyons, a St. Louis newspaper printed a letter to the editor from members of the Four Hundred Club, stating that “Mr. Lee was our captain. We deeply regret the situation into which our unfortunate … brother has fallen.”

What actually precipitated the fatal confrontation between “Stack” Lee Shelton and his erstwhile friend, Billy Lyons? According to the lines in the song, it was over a game of chance:

Stagger Lee says to Billy,

I can’t let you go with that.

You done won my money,

You can’t have my Stetson hat!

In fact, if the local newspapers are to be credited, the altercation was political in nature. Apparently, Billy was a Republican. The discussion grew increasingly heated, and fueled by a significant intake of spirits, Lee dented Billy’s derby, whereupon Billy grabbed the Stetson from Lee’s head. Lee threatened to shoot Billy unless he returned the hat forthwith:

I got a brand new razor,

Got a big old .41.

If you stay, I’m gonna cut you down,

Gonna shoot you if you run.

Billy refused. Taking a knife from his pocket, he proclaimed, “I’m going to make you kill me!”

Lee hit him on the head with his pistol, which was actually a .44-caliber Smith & Wesson. When that failed to produce the desired results, Lee fi ed a round into Billy’s abdomen. As Billy staggered along the bar, clutching the rail, Lee walked up and, retrieving his Stetson, said, “I told you to give me my hat!” He then turned and walked calmly home. Billy Lyons succumbed the next morning, one of five murder victims in St. Louis that Christmas Day. Lee was arrested, tried, and—after two trials—sentenced to twenty-five years in the Missouri State Penitentiary.

However, practically all the various iterations of the song have Stagger Lee executed for his crime:

Judge stood in the courtroom,

Said, Mr. Stagger Lee,

I’m gonna hang your body high,

Gonna set your spirit free.

In reality, Lee Shelton was paroled in 1909 but found himself in trouble again just two years later. This time, there would be no parole; Stack Lee died of tuberculosis in the prison infirmary in early 1912. The disease had taken a terrible toll, and the unromantic truth is that by the time he died, the pimp, gambler, and murderer weighed only 102 pounds.

The folk versions are much more dramatic. In a number of variations, even death itself is not the end for Stagger Lee. On attempting to enter heaven, he is rebuffed at the gates by St. Peter:

Stagger Lee went to Heaven,

And he met St. Peter there;

Says turn around, go down the other way, we don’t

Allow no gamblers here!

The only remaining option for the deceased killer is hell, and again Stagger Lee asserts himself, this time for control over the Devil’s domain:

Stagger Lee told the Devil,

He says, “Git up on your shelf!

My name is Stagger Lee, I’m gonna

Run this place myself!”

Even in death, the larger-than-life figure of Stagger Lee triumphs.

It is unfathomable why the obscure murder of a levee hand in a red-light bar would attain such far-reaching notoriety, while songs about equally sordid killings—fact-based murder ballads such as “Ella Speed” and “Duncan and Brady”—are doomed to relative obscurity. Nonetheless, “Stagger Lee” spread with extraordinary speed, beginning shortly after the actual killing. It was soon being sung in various forms by workers on the levee, convicts on chain gangs throughout the South, saloon and street singers, and even school children. Soon, the musical, mythical iteration of “Stack Lee” supplanted the man himself, as black America cultivated and nurtured a heroic outlaw to admire.

In the past several decades, artists of all genres and background have taken to the song. A dedicated online site—The Definitive List of Stagger Lee Songs—names 426 distinct singers who have put the song on wax or vinyl. They include such exalted artists as Ma Rainey, Cab Calloway, Jimmy Dorsey, Duke Ellington, James Brown, Fats Domino, Peggy Lee, Bob Dylan, Woody Guthrie, Carl Sandburg, Mississippi John Hurt, Doc Watson, Pete Seeger, Ike and Tina Turner, Nick Cave, Amy Winehouse, Taj Mahal, Wilson Pickett, Elton John, Leon Russell, the Grateful Dead, Huey Lewis, Beck, the Black Keys, and the Clash. However, the definitive version of the song came out in 1959 when rhythm-and-blues singer Lloyd Price topped the charts with his snappy, horn-drenched version.

As a man, the lowlife pimp and murderer Lee Shelton has all but sunk into obscurity. However, as raised up by more than a century of popular culture, the righteous killer Stagger Lee has become an icon to generations, who see in the folk character a defiance of authority, pride of self, and strength in the face of adversity.

Related Posts

Paul Harvey: The Rest of the Story

America’s number one talk show host who hails from Cape Girardeau. I’m talking about Paul Harvey, whose daily broadcast The Rest of the Story aired on more than 1,100 radio stations for thirty-plus years.