A Missouri town recalls a tragedy that fell from the skies sixty years ago.

A thunderstorm swept through the town of Unionville just before dark. That was hardly unusual for a springtime evening in Missouri. The storm passed, the rumble of thunder grew more distant, then all was silent except for the nighttime sounds of a small town on a rain-washed Tuesday night.

At around 9:20 PM, the peace in the Missouri/Iowa border town was shattered by a loud, explosive boom.

It wasn’t thunder.

On May 22, 1962, Continental Flight 11, a Boeing 707, left Chicago, heading to Los Angeles with a scheduled stop in Kansas City. It never arrived.

The unassuming north central Missouri town of Unionville, with fewer than two thousand residents, became the site of Missouri’s worst air disaster and an early domestic air terrorism event. The jet plummeted from an altitude of thirty-five thousand feet. When it came to rest on the ground, the tail section was in Iowa. The fuselage that held forty-five passengers and crew fell into Missouri farm fields.

Two couples from the neighboring town of Centerville, Iowa, were returning from an evening out in Unionville. Leo Craver, Jack Morris, and their wives came upon plane debris in the highway several miles south of Centerville and contacted law enforcement. Back in Unionville, Putnam County Hospital Director Charles Judd, who also served as county coroner, answered a phone call he never imagined getting. He and Sheriff David Fowler were among the local emergency personnel alerted about the crash.

“We had a party-line phone,” Ronnie says. “and it was ringing off the wall.”

They listened to what others were saying about what they had heard and used the information to narrow down the area for their search.

“We walked through the brush and tall weeds,” says Ronnie, now seventy-seven. “It took a good hour to find the wreck. The flashlight batteries went out soon. It was muddy from the storm, and hardly anyone had four wheel drive vehicles. If you didn’t have a tractor or a horse, you had to walk.

“We walked up a hill. It was about four in the morning. There was a tree across the ditch I was going to walk across. Dad said ‘No, let’s go this way.’ Later we found a guy (from the plane) who hit a stump. I would have stepped right on what was left of him, but I listened to Dad for once. It was quite a mess. Some people fell out of the plane.”

‘There’s dead people in there’

The last of the clouds had cleared and the moonlight revealed a horrifying scene.

“It was a scary thing,” Ronnie says. “I can still see that plane shining in the moonlight.”

He got on a wing, and his father ordered him off, saying, “There’s dead people in there.”

It was logical to assume that Flight 11 was downed by lightning from the storm that rolled through just before the crash, but the ensuing investigation uncovered a much more sinister scenario.

The condition of some of the deceased passengers belied the violence of their death. “One guy in a suit was in his seat,” Ronnie says. “The coroner said the guy’s suit wasn’t ruffled a bit.”

Terry Bunnell, now eighty-four, farmed some of the crash site fields and was also part of the early search for the wreckage.

He recalls that neither the pilot nor the co-pilot’s clothes were dirty. Other victims suffered a more gruesome fate and morning light brought the grim scene into focus. The tragedy didn’t mean that Unionville’s students got a day off from school, so Ronnie went home, got cleaned up, and caught the bus.

From his vantage point on the school bus, he could see bodies that had fallen into the trees a few hundred yards from Route UU. One of the dead passengers suspended in the trees was a man named Thomas Doty.

A suicide bomber?

It was logical to assume that Flight 11 was downed by lightning from the storm that rolled through just before the crash, but the ensuing investigation uncovered a much more sinister scenario. A Kansas City salesman named Thomas Doty brought six sticks of dynamite on board the flight and detonated them in the lavatory towel bin. Doty had been arrested a month earlier for the armed robbery of a Kansas City woman. His hearing was set for later in May, and he reportedly told friends he would commit suicide before facing trial.

Doty was married with a young daughter, and he purchased $300,000 worth of life insurance prior to his death. The insurance money for his family might have been his motive for mass murder, but when his wife tried to collect on the policies, she was denied because his death was ruled a suicide.

The suicide bomber was traveling with a woman named Geneva Fraley, of Kansas City, Kansas, with whom he was planning a business venture. They almost missed the Chicago flight, but the ticket agent called for the stairway to be moved back so the couple could board, which was a common practice in the days before strict airport security.

The passenger manifest read like a Who’s Who of business executives: US Medal of Freedom recipient and Chrysler Dodge manager Fred P. Herman and two of his colleagues, six managers of the Michigan Wisconsin Pipeline, and executives with Vanilla Laboratories, Lenora Lingerie, Futursonic Production, and Aeroquip Corporation.

Arthur Hailey’s novel Airport and eventual movie of the same name were partially inspired by the crash of Continental Flight 11 near Unionville.

Robert L. Miller was a uniformed soldier returning to Fort Riley, Kansas, after a furlough in Chicago. The lone female passenger was Doty’s traveling companion, Fraley. Passenger Takehiko Nakano, twenty-seven, an engineer from Illinois, initially survived, but died in a Centerville, Iowa, hospital ninety minutes after being transported from the crash site.

Prior to the crash, Continental Airlines had flown several billion miles in twenty-eight years without a fatality accident. Pilot Fred Gray had logged more than twenty-five thousand hours of flight experience.

A previous brush with peril

This particular plane had already achieved notoriety. It was hijacked in August 1961 by two Fidel Castro sympathizers. That flight crew convinced the hijackers that the plane needed refueling in El Paso, Texas, where the hijackers were arrested after a brief hostage standoff.

On May 22, 1962, Flight 11 departed Chicago at 8:35 PM. Captain Gray had permission to move over and around a thunderstorm that stretched across northern Missouri and southern Iowa. At 9:17 PM the plane disappeared during a routine radar transfer from Waverly, Iowa, to Kansas City and was not picked up on radar again.

Soon there was a line of traffic passing by on the dirt road near his home. Terry followed the smell of jet fuel to the crash site. He was disappointed to discover that some people were macabre souvenir hunters, seeking wreckage pieces or even victims’ items. Souvenir hunters continued to show up for weeks after the incident.

“One souvenir hunter brought a woman to fix me up for a date in exchange for being able to hunt souvenirs,” Terry says. “I was married and had a child. I just looked at him and didn’t answer him.”

A town in mourning

Wreckage was strewn from north of Unionville, Missouri, to, coincidentally, Unionville, Iowa, some thirty air miles away. During the jet’s uncontrolled nosedive, all four engines tore away from the wings and eventually embedded themselves deep into the soft earth. Longtime resident Judy Pauley remembers the heartbreaking days following the crash.

“Early in the morning, Merle Husted of Husted Funeral Home called my husband, Bill, and told him there was a terrible plane crash north of town. Bill got up but wasn’t gone long. They would have to wait until the authorities got there before the bodies could be removed. Merle called back later in the morning, and I didn’t see Bill again until the next day.” Bill Pauley described the scene to his wife.

“He said it was like the plane was set down and opened with a can opener,” Judy says. “He had nightmares after that. He kept seeing all those people. After that, Bill had a phobia of flying. When we had to fly, he asked the doctor for medication to help him.”

Among the authorities who descended on Unionville following the crash were representatives from The Civil Aeronautics Board, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, and the US Weather Service. The FBI team was led by Mark Felt, who later went to Washington and was eventually identified as the “Deep Throat” informant in the Watergate scandal.

“Iowa wanted to run the show,” Ronnie says. “Some authorities wanted to take the bodies over to Iowa. Dr. Judd, the coroner, said, ‘The heck you are!’ and called the Missouri Attorney General Thomas Eagleton. There was no horseplay with him.”

Did a lone German shepherd survive this horrific crash? Read the story.

Thirty-seven bodies were found within twelve hours of the crash and taken to a makeshift morgue in the basement of a vacant Ford garage in Unionville, Missouri. The street to the morgue was closed. Terry remembers that bodies were placed on ice there. Another seven bodies were found on May 23, but one was still missing.

“One stewardess wasn’t immediately found,” Ronnie says. “Someone asked the junior and senior (Unionville High School) boys to help look for her on Thursday morning. We walked so far apart. We found silverware and pieces of the seats. One boy, Johnny Mack Buckalew, found her a mile west of the crash. I’m glad I didn’t see her.”

Judy says that the people of Unionville responded well to difficult circumstances.

“It was before the dial phones,” she said. “We had telephone operators. Those ladies worked around the clock taking phone calls. The town was in mourning. There were so many victims. The town rallied. The National Guard stayed in the high school gym. Churches took turns feeding the National Guard and those with the airline.”

Terry thinks the victims and their families were always kept at the forefront of the community’s response.

“It was respectful the way the bodies were treated,” he says. “One family called and wanted me to sow poppy seeds at the site where their son was killed. I did, but I never went back to see if they grew. Even now, the crash still bothers me. People have asked me about it. Sometimes, I don’t tell them how bad things were.”

Related Posts

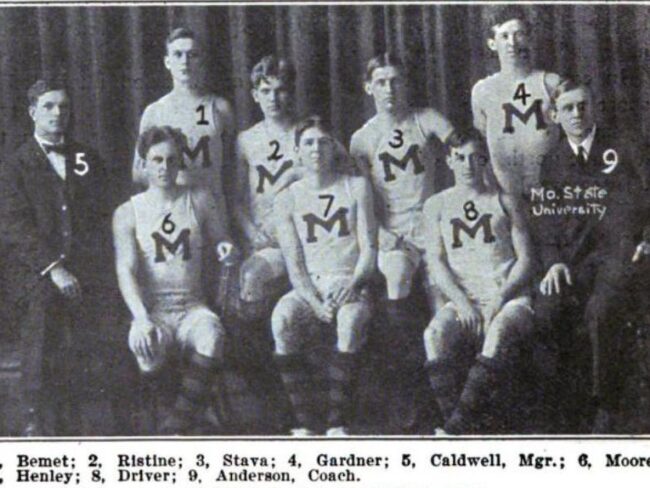

The Border War Reaches the Basketball Court: March 11, 1907

The University of Missouri Tigers met the Kansas Jayhawks basketball team for the first time, beginning the basketball Border War. Missouri won 34–32. They played again the very next day and Missouri won 34–12.

January 11, 1865

Since Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation did not cover Missouri, the state’s Constitutional Convention voted on this day to abolish slavery in Missouri. Missouri was the first former slave state to do so.

December 11, 1919

Robert Pankey of Eldorado Springs was a model youth. He was said to never swear, smoke, or touch liquor. But, on this day, he held up the Bank of Washburn and took $12,850.