But now the Rock Island Line doesn’t run anymore,

Though miles and miles of railroad track lay right outside my door.

And sometimes when I lie awake and the night is draggin’ by,

I miss those trains that used to run that Rock Island Line.

My friend Levan Guinn’s snappy but melancholic tune plays a loop in my mind. Closing my eyes, I squint hard to bring long-ago memories back into focus. The sight of “my” old Rock Island railroad corridor catches my breath, though I know the rails, ties, and spikes were pulled up three years ago. There behind the lake at Belle City Park, a soul-deep wave of nostalgia stirs more than I expect.

I slowly open my eyes, brush away a tear or three, and imagine twelve-year-old me, deciding which way to go. To the west was the railway path to untold hours of exploration and adventure—my main playground for the years that linked adolescence to teenage—and about seven miles to reach the most wondrous sight I’ve ever seen in my native Missouri: The Gascondy Trestle, a majestic bridge that towers one hundred feet above the Gasconade River, joining Summerfield and Maries County to Freeburg and Osage County, seven miles or so to the west. When I was eleven, the first time Levan’s dad, Leroy Guinn, led me and my pals to the Gascondy, it seemed like fifty miles.

I’m at once eager and reluctant to turn my gaze east, where just a short quarter mile down the tracks, the Guinn house sat on a high berm next to the railroad. Across the street was my old house, a green duplex. Back in the day, I had the best Wiffle ball field anywhere. My bedroom window, a mere

seventy-five feet from the tracks, was the left field foul line. The roof was the left field “fence,” thus we called the field “Little Fenway,” our equivalent of Boston’s “Green Monster.”

Speaking of monsters, the first verse of Levan’s plaintive Rock Island song goes like this:

When I was a young boy, lyin’ in my bed,

The moonbeams on the window pane

made monsters in my head.

And then I’d hear that midnight train, rollin’ into town.

And I would not feel so all alone

when I heard that whistle sound.

Bad Luck

The Chicago, Rock Island, and Pacific Railroad was beleaguered for three quarters of a century by government regulation and red tape, head-scratching internal financial decisions, failed merger attempts, questionable competition from other rail lines and other transportation industries, and the slow but sure shift from a manufacturing to a service economy. One example: the federal government bailed out barge operators in the 1930s when many railroads, the Rock Island among them, were struggling to stay afloat. Then state and federally funded highways provided arteries for the trucking industry, though the industry didn’t pay to build the roads and highways.

As early as 1911, Rock Island’s annual report mentioned the “unfair competitive advantage” that a growing trucking industry could have as more and better roads were built with public funds, with no investment from the trucking industry. Meanwhile, railroads used precious capital to build their lines, with restrictions and regulations set by the feds. Once a shining, speeding star in the country’s storied railroad history, the Rock Island’s final death throes began, many historians and analysts believe, when the Rock lost the US mail contract in the late 1950s.

Fast-forward to the final chapter, the Rock Island Line was seeking its fourth bankruptcy, when the Rock Island was unable to stave off a workers’ strike in August 1979. A federal bankruptcy judge ordered the Rock liquidated, and the legendary rail line officially ceased operations on March 31, 1980, ending service on 7,300 miles of track in twelve states.

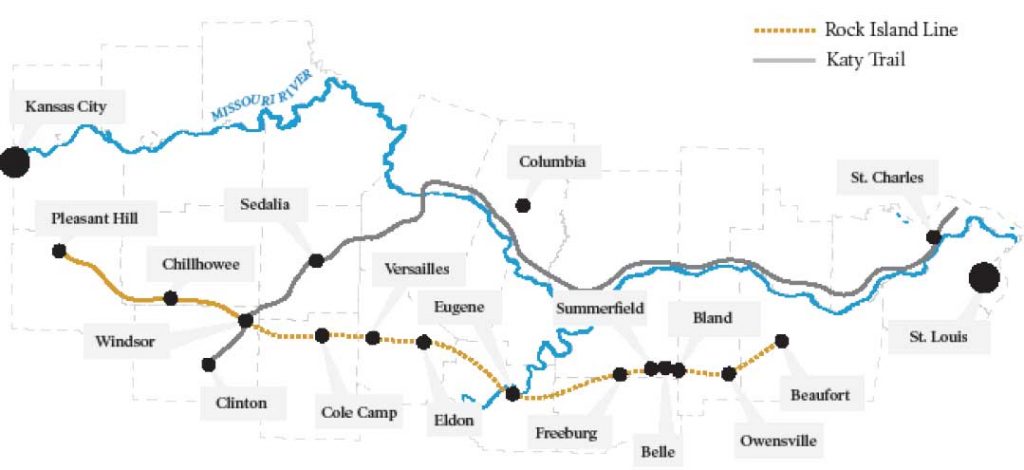

Only faint scars remain to indicate that for nearly eight decades, railroad tracks dominated the now-green corridor. The only remnants are splinters of long-ago, creosote-soaked railroad ties in the rocky soil. The entire corridor spans 144 miles from Pleasant Hill to Beaufort, with more stretching west to near Kansas City and east to Washington.

Though lifeless for forty years, the scenic rail bed in the Ozark foothills could get new life as a trail, a skinny state park that, when linked with the Katy Trail, would create a 450-mile loop for recreation, including walking, bicycling, and horseback riding in some areas.

That dream got a new head of steam at the end of 2019 when the Department of Natural Resources signed an interim trail use agreement with Ameren to transfer ownership of the corridor if the Missouri State Parks Foundation can raise $9.8 million for initial development, security, and management costs. The Foundation has two years.

New Opportunities

The fundraising stipulation is daunting, but Greg Harris, executive director of the nonprofit Missouri Rock Island Trail Inc., says many communities with the rail path in the center of town hope to develop their own sections of the trail, relieving State Parks from the entire cost. Greg seems the ideal person for the job, considering his past work aiding a former mayor of Columbia, the late Darwin Hindman, and others in pursuing and promoting the Katy Trail.

Greg is a cyclist, too, at ease biking the Katy Trail and enthusiastic about the prospects of doing the same on the Rock Island Trail. But Greg and MoRIT board members and advocates say it’s about more than people who simply want another trail to ride their bikes on. It’s about preserving history and new opportunities for twenty-three communities along the old Rock Island corridor. A University of Missouri Extension economic impact study determined that Katy Trail use generates $18 million annually in tourism dollars. Greg also cites the demographics highlighted in a 2012 report about the Katy Trail’s impact, which showed that about one-third of the 400,000 annual visitors are from other zip codes and many have incomes exceeding $100,000 or greater.

Greg and MoRIT, along with a consortium of other trail advocacy and outdoors groups, including the Audubon Society and the Rails to Trails Conservancy, champion the Rock Island Trail as important to improving the quality of life and transportation across and between towns, “and drawing people into their communities who would otherwise never go there and spend money.” He adds confidently, “We anticipate it will be at least as productive as the Katy Trail.”

Most of the communities between Beaufort and Windsor have plans or hopes for making new use of their sections of the corridor. Owensville city and school officials envision using the trail for a safe walking and biking route to school where the trail passes under busy Highway 19. Eldon has sights set on the trail as a draw for senior-living housing and recreation, and Belle has a community improvement plan along the corridor. Some small towns near but not on the trail corridor, Cole Camp in Benton County, for instance, are hoping to connect with the trail and its potential.

The trail will go over six bridges and through three tunnels. The Gascondy Trestle is perhaps the gem of the lot, spanning the Gasconade River, one hundred feet above.

“It runs through some really gorgeous settings,” Greg says.

Though state ownership isn’t final, another portion of the cross-state trail is already underway: a 24.8-mile stretch from Pleasant Hill to the Kansas City Truman Sports Complex. According to the plan, once State Parks builds the cross-state trail, it will add another extension from Beaufort to the Katy Trail State Park at Washington. There’s also now a rumbling expectation that the trail could extend all the way to St. Louis.

MoRIT recently received a $20,000 grant from the Rails to Trails Conservancy to inspect and plan repairs for the Soap Creek railroad bridge and the Old Highway 50 bridge, both east of Owensville. And the Gascondy Trestle has received a passing grade from engineers.

“We’ve had lots of engineers look at it,” Greg says. “Missouri State Parks and all the engineers we’ve had look at it say they don’t see a problem with it.” The cost of putting down a surface for walking and riding a bike and installing railing for protection—well, that’s another issue. It could be millions of dollars.

Ameren commissioned a survey of the old rail corridor, and a State Parks’ engineering report describes every bridge as being in good shape, with the exception of the Old Highway 50 bridge east of Gerald.

The Memories

Derailments weren’t uncommon, especially in the stretch from Summerfield on the east side of the Gascondy Trestle to Bland. But the trains weren’t exactly moving at break-neck speed then, so there was little harm to life. Levan Guinn remembers a time when a box car filled with Southern Comfort whiskey derailed at Bland.

“There were people grabbing cases of whiskey,” he says with a slow smile spreading across his face, but he’s not naming names.

“Oh, the memories. I still get excited when I smell creosote,” he says. “I would love to get out on that trail again.”

Levan and his pals were a few years older than me, but my main posse included his two brothers. We share similar memories about exploring and hiding in the tunnels and culverts that ran beneath the tracks in a few places. Long hikes to nowhere in particular, following the rail—and listening for the train—until there were no more snakes and lizards to chase, animal bones to collect, or shenanigans to get into. Two of Levan’s friends once drove their dirt bikes across the mighty Gascondy.

“You’d put pennies on the track, see all kinds of lizards and rabbits. You were just out there. Free. It was just fun,” he recalls. Along with his two pals, the mischievous trio wanted to see what was in a tanker car stopped on the tracks. They worked together to loosen the big wheel that opened the spigot. As molasses began dripping out, “clunk,” the train began moving along.

I was sixteen when the Rock Island stopped running. I apply the term “running” rather subjectively. Toward the end, the massive old locomotives and box cars rumbled slowly. Our regular cast of characters would race alongside, often keeping pace for a half mile or more. Once, the train engineer hollered at us to keep clear and get off the tracks. We were trespassing. Naturally, we saw the train as an intruder on our thoroughfare, and one of my friends—of course, I would never have spoken to an adult like this—said some brave, choice words, followed by, “What are you gonna do about it?”

Quicker than the train ambled along, a stout man emerged from the back of the locomotive, hopped off, caught his balance, and began the chase. We dove into a thicket through briars and saplings that whipped hard if you were the one in the rear. Escape wouldn’t have been likely had the daring encounter occurred closer to Summerfield and the wondrous Gascondy Trestle, which offered fewer places to hide.

Scenery and Sound

The stretch of tracks from just past the Belle City Park all the way to Summerfield was blazed and dynamited through hard clay and limestone, forming a narrow canyon in which to lay ties and rails. That majestic site of mostly man-made bluffs was a vision that scant few people apart from railroad workers would ever see. There was no public access to most of that route except for tumbling down a rocky wall or, as we preferred, following the tracks to the next adventure.

The Rock Island was just one of scores of rail lines tunneling through rock, burrowing through bluffs, and constructing massive wood or steel trestles that spanned rivers and valleys so the rails could transport coal and countless other minerals or fuel, livestock and grain, rock and sand, cars and trucks, and building products. But those often breathtaking byproducts—the vistas and the bluffs—are now the main attractions for bicyclists, hikers, and preservationists yearning to see the Rock Island Trail become a reality.

Back in the early ’70s, Levan drove from Belle to Jefferson City to work at Chesebrough-Ponds, the former health and beauty product manufacturer. One of the machines he operated made Q-tips.

“A hundred machines, they would get in sync, just for a second, and they would sound like a train moving,” he says. It filled him with a sense of comfort, remembering the Rock Island crewmen hollering to each other out on the railroad track late at night, a sort of sing-song quality that Levan says chased away any shadowy monsters on his wall.

“It made me feel safe, hearing adults who were working. There was just something about it,” he recalls. “I could go on to sleep.”

Levan also used the rumble of the train to successfully sneak in past curfew. When the cacophony of machines later reminded him of the old Rock Island, he wrote the song in his head.

“I came home and played it on the guitar,” he recalls. “It all came to me at once.”

When I was a young man, I’d go out on a date.

My dad said ‘Be home early son,’

but I’d always come home late.

Well I knew that I would wake my dad

if I tried to sneak inside.

So I’d wait and slip in when

that midnight train went rumblin’ by.

The Long View

“The old saying, ‘Rome wasn’t built in a day,’ it applies to this, too,” says B. J. Friedly, executive director of the Windsor Chamber of Commerce and one of the trail’s strongest ambassadors. “Thirty-somethings with kids have decided to come home and raise their families. Many bought property knowing this was a possibility. Windsor is in a unique position simply because it’s at the crossroads.”

Indeed, the Katy Junction there is the spot where the Katy Trail and the so-called Rock Island Spur intersect, with the Katy crossing the Rock Island with a bridge. Dale Eckhoff came back home to Windsor to start the Katy-Rock Junction, offering tent camping and sleeper cabins for trail users. Just a stone’s throw from his property is Kim’s Cabins, which has already expanded from four beds to seventy-six. Camping at Windsor’s Farrington Park, donated to the city by a former Rock Island executive, increased 400 percent since the first portion of the Rock Island Trail from Pleasant Hill to Windsor opened in the fall of 2018.

The trail has already led to some small businesses either opening or expanding, says Windsor Mayor Rick Rollins, adding, “They bring in bigger ones.”

Hurdles remain, chief of which is the price tag of trail development, an estimated $65 to $80 million, compared to the annual State Parks’ budget of around $60 million, and opposition from landowners, some of whom have used portions of the abandoned rail bed as part of their farming operations. It’s not dissimilar to the chronology of opposition to transforming the abandoned MKT rail corridor into the Katy Trail.

The essence of the argument is that railroad easements from the 1890s stipulated that the property used for the railroad would revert to landowners in the event the rail was abandoned. In 1983, an amendment to the National Trails Systems Act created a provision that allowed preserving abandoned railroad corridors for uses other than a railroad. That’s the federal act that trumped landowner opposition to the Katy Trail and which will almost certainly settle the debate in favor of the proposed Rock Island Trail.

A Little Respect

“It’s still not a trail. Some people think it is, but it’s not,” says Butch Hilkemeyer, owner of Hilkemeyer General Store in Freeburg. His family has owned the land on the west side of the Gasconade River where the Gascondy Trestle meets Freeburg since the 1970s, back when the trains were running.

“I’m going to be neutral on this. The trail will be what it is,” he adds. “But it’s still Ameren’s property” for now, which means, technically, anyone on the rail bed is trespassing. Butch says Ameren provided property owners along the corridor with signs to warn against trespassing.

“The local sheriff’s department has better things to do” than chase down rail bed interlopers, he says. “I’m not for it or against it. Just respect our property lines.”

At the signing ceremony in Eldon last year, State Parks Director Mike Sutherland acknowledged the importance of working with affected landowners.

“We want to be respectful of the property owners along the corridor, so we have had a lot of interaction with them,” he said. “We’re trying to find a path forward.”

Trail advocates point to the Katy Trail as an obvious case study for their cause. Another more recent demonstration of trail benefits and assuaging landowners’ concerns is Gerald Cox’s cattle farm just outside Windsor. The Rock Island corridor bisects his farm, and when the Rock stopped running, Gerald, like many of his neighbors and countless others along the corridor, began using that part of the property. He was able to move cattle from pasture to pasture across the old rail line.

He was worried about—“dreaded,” he told MoRIT’s Greg Harris—how the trail would affect his operation.

“I’ve had no problem so far,” Gerald explains. Trail users have been respectful. He’s met folks from all over the country, and once a woman who hurt her leg came to his house to use his phone. Trail costs covered installation of a fence and gates that allow him to move cattle across the trail.

“The way it’s turned out, I consider it to be pretty nice,” he adds. Gerald also received a check recently for a portion of the right-of-way, so he’s even happier, considering that the property hadn’t really been his to use, he concedes.

“In good weather, my wife walks on it about every day,” Gerald says, and sometimes they’ve ridden their bikes on the trail, which is about a hundred yards from his house.

Greg likes to cite Gerald’s change of heart as evidence that other property owners will soften their opposition to the Rock Island Trail. Greg notes that in thirty years, there’s never been an arrest on the Katy Trail, “and it’s not because they got away. It’s just that there’s nothing to arrest anybody for. You don’t really have to worry about somebody stealing your flat screen TV and carrying it home on their bike,” he says. “It’s just not going to happen.”

Faster Development

“It would be a shame to lose a 144-mile rail corridor—lost to the public forever,” laments Chrysa Niewald, a past president of MoRIT and a retired high school teacher, who taught in both Belle and Owensville. “We’ve been working on this so long; it was almost a done deal” more than once.

The Rock Island Trail was a bright possibility as far back as 1993, but a proposed purchase of the rail corridor by a Canadian investment firm stymied trail plans. The purchase eventually fell through. Then in 2009, a group that included Chrysa began eyeing a trail for the thirty-five-mile stretch of rail corridor from Belle to Beaufort. As other organizations and communities took interest, the short stretch became a 144-mile stretch for the entire Pleasant Hill to Beaufort trail.

Getting a positive reception for the plan was difficult during Gov. Jay Nixon’s terms, partly because the legislature was sour over State Parks’ acquisition of several new parks. State Parks is part of the Department of Natural Resources, which has somewhat autonomous responsibility for its budget, and the legislature took exception.

“I used to teach government,” Chrysa says. “But politics is a lot different than government.”

Now that the political climate has warmed to the Rock Island Trail idea, she hopes progress can move more quickly.

“Smart Men”

A 1905 Rock Island pamphlet extolling the virtues and hardiness of Missouri folk along the new rail line noted that little towns would gain life and become bigger towns, and some new towns would crop up because of the iron rails that carried the Rock Island trains through their neck of the woods. Rock Island’s public relations team urged “smart men” to capitalize on the growth, start their own businesses, and take advantage of the rail line’s ability to transport clay, wheat, livestock, and other agricultural products.

In addition to the towns still existing—Eldon, Windsor, Belle, Barnett, and more—the who’s who and where’s where of place names in the Rock Island’s inaugural years included Marvin in Morgan County; Hoecker and Etterville in Miller County; Crest, Nay, and Brandon in Benton County; Bowen in Henry County; and Post Oak and Medford in Johnson County.

The corridor’s future isn’t yet crystal clear, but Greg has no doubt that the Rock Island Trail will become reality.

“Our organization’s all about making this trail happen and getting it going,” he says. “I just want people to know: it’s going to happen.”

Greg puts an exclamation on his confidence with an outdoorsy analogy: “The fish is on the stringer.”

The Rock Island Line Doesn’t Run Anymore

The final verse:

Now I am an older man with a young son of my own.

I know sometimes he lies awake feelin’ scared and all alone.

And it makes me feel a little sad when I think of days gone by.

He’ll never hear those trains that ran that Rock Island Line.

But now the Rock Island Line doesn’t run anymore

Though miles and miles of railroad track lay right outside my door.

And sometimes when I lie awake and the night is draggin’ by

I miss those trains that used to run that Rock Island Line.

No, he’ll never hear those trains that ran that Rock Island Line.

To hear the song, visit youtu.be/t9O2_uYS1d8

Related Posts

Arrow Rock’s Hidden Black History

The National Historic Landmark Village of Arrow Rock Embraces its Diverse Past.

The Rock Island Trail Connects KC to the Katy

The Rock Island Trail, connecting the greater Kansas City area to Missouri’s Katy Trail system, is an experience to savor whether you are walking, cycling, or on horseback.