This is the seventh story out of nine in a series dedicated to Missouri’s Bicentennial. Read the rest here: one, two, three, four, five, six, eight, nine.

On a November evening in 1953, a group of Black people approached the ticket office at Uptown Theatre on Broadway in Columbia and requested tickets to the evening screening of Martin Luther. The ticket seller told them the show was sold out. But when the next White couple came up to the box office, they got tickets. Other small groupings of Black patrons tried to buy tickets. Repeatedly, they were told the show was sold out, although White patrons had no trouble purchasing tickets.

Soon, an interracial group of students and community members began protesting outside the Uptown entrance, explaining to passersby that the theater’s manager were openly discriminating against Columbia’s Black community.

Often we think of the civil rights movement of the twentieth century as having taken place largely in places like Alabama and Mississippi, but Missourians were taking action to support equal rights, too. Student and community groups in Columbia, Jefferson City, and St. Louis in particular played a role in this fight and, in some cases, were ahead of the national curve. Civil rights protests in Missouri since this period have built on and paid homage to the legacy of earlier activists.

In recognition of both the state’s Bicentennial and Black History Month, we take a look at aspects of the struggle for civil rights in Missouri that laid the foundation for lasting change.

Many Americans regard the beginning of the civil rights movement as sometime in the mid-1950s, starting either with Brown v. Board of Education or perhaps the Montgomery Bus Boycott. Although there’s no question these events played a significant role in accelerating the national momentum of the movements, Missourians were protesting for equal rights well before these seminal events.

The students and community members who participated in the stand-in outside Columbia’s Uptown Theatre were members of the local Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) chapter, a civil rights organization, which started in 1948. The Columbia members took their cue from St. Louis CORE chapter members, who had been conducting sit-ins in downtown department stores and drugstores since 1948.

Sit-ins conducted by CORE in St. Louis during the late 1940s weren’t the first the city had seen. An all-female group called the Citizens Civil Rights committee began conducting sit-ins in 1944.

Nonviolent student-led campaigns across the country dated back to the early 1900s, and the efforts by college activists in St. Louis and Columbia to desegregate campuses and challenge racial injustice off campus at theaters, restaurants, and lunch counters during 1952 and 1953 firmly contextualize Missouri’s early role in the civil rights movement.

The end of World War II was followed by an explosion of student veterans entering colleges across the country. Many student veterans, both Black and White, came home with a new sense of purpose in relation to racial inequality—they wanted to push for the same kind of democracy at home that they had fought for in Europe and Japan. Student veterans joined campus organizations, including student government, student publications, and veterans’ groups, and worked to make restrictive campuses open to Black students. Both the University of Missouri (MU) and Washington University (WU) prohibited enrollment of Black students.

White student veterans who attended MU and WU on the GI Bill helped organize local chapters of the American Veterans Committee (AVC), whose national leadership embraced efforts to better race relations. The Columbia AVC chapter met jointly with the AVC chapter at Lincoln University in Jefferson City. These meetings offered opportunities for members to talk about race relations in the national context and in their local communities.

At MU, student veterans often used their participation in other campus organizations as a way to initially bring up race relations and then more broadly push for desegregation. For example, in 1947, a campus literary publication, Towertime, ran an article by Jon Moon, which argued that the time had come for university officials to confront the question of race on campus. When Editor Jack Scwhartz refused to pull the article, the publication was suspended. Pressure to desegregate was increasing but campus administrators largely remained silent.

Other MU student publications and student government leaders took on the desegregation cause by publicizing their support of the proposed House Bill No. 182 that passed the Missouri House in 1949 but stalled in the Senate. House Bill No. 182 would invalidate or clarify the “separate but equal” doctrine related to education in the Missouri Constitution. The bill stated that MU (and other state institutions of higher education) had to admit Black students if the programs they wanted to enroll in were not offered at Lincoln University, the state’s historically Black college and university.

The reach of student support extended off-campus when student leaders worked alongside social organizations, like the Missouri Association for Social Welfare, and journalists in voicing their support of desegregation. The death of House Bill No. 182 did not end the push for desegregation, and in February 1950, Elmer Bell Jr., George Horne, and Gus T. Ridgel filed suit against the University of Missouri for denying them admission based on their race. The case was heard in Cole County, and in June 1950, Cole County Circuit Judge Sam C. Blair ruled that MU must admit Bell, Horne, and Ridgel, resulting in the desegregation of not only MU, but the public colleges and universities in the state. Dr. Ridgel would go on to become the first Black graduate of MU. He earned a master’s degree in economics the following year. He passed away last June.

At WU, the AVC in 1946 and 1947 publicly supported the admission of Black students. AVC members worked to broach the conversation of race relations among the campus community by holding lectures and events on campus with a plethora of speakers, including Paul Robeson and A. Philip Randolph.

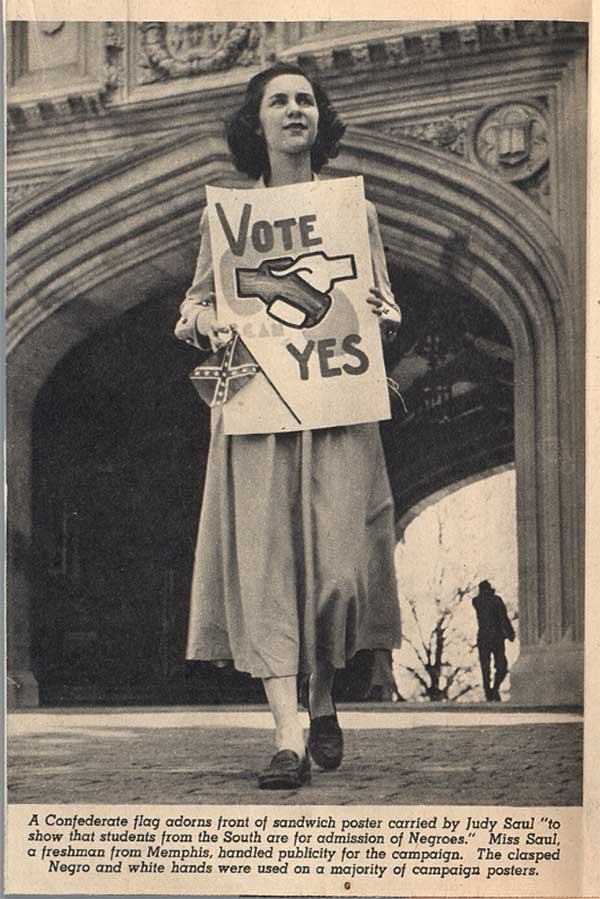

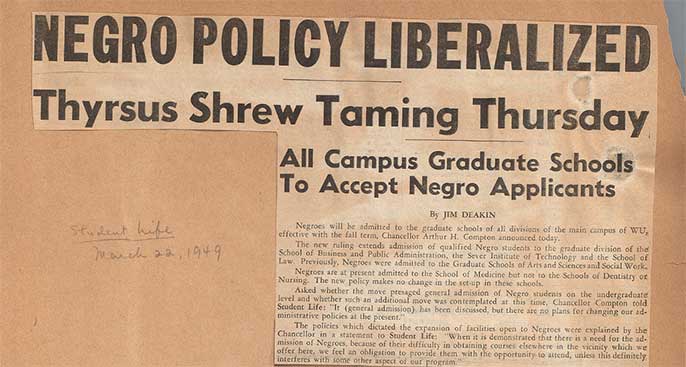

WU opened admissions to African Americans in 1947 at the School of Medicine and the George Warren Brown School of Social Work, although the first Black medical student was not admitted until 1951. At the beginning of 1949, students in favor of desegregating the rest of the college organized to form the Student Committee for the Admission of Negroes (SCAN).

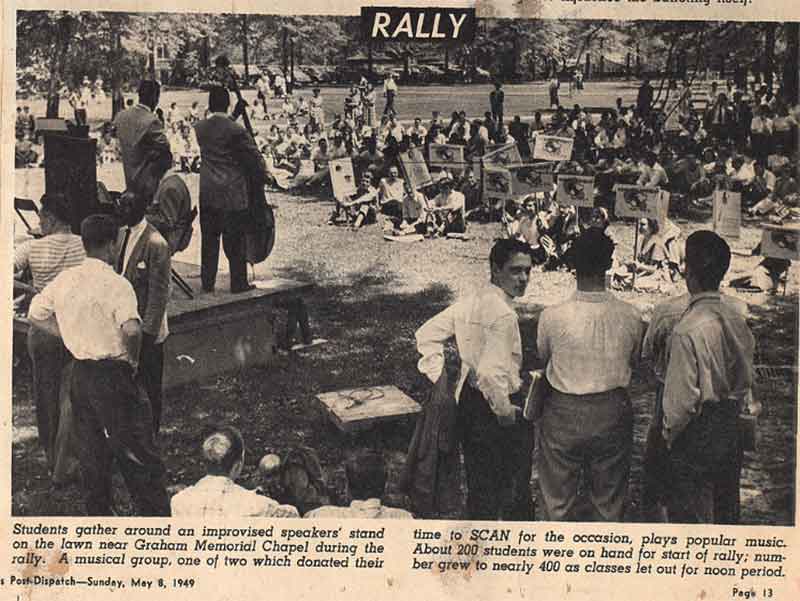

SCAN members organized panel discussions and lectures, as well as protests where members carried placards advocating for desegregation. In May 1949, SCAN organized a poll of WU students to gauge their opinions regarding the admission of Black students. The poll showed the majority of students supported the administration changing admission policy with 1,767 voting for the changes while 516 voted against. The administration desegregated the remaining graduate programs in 1949 and 1950.

In 1951, there was renewed support for undergraduate desegregation when the campus newspaper, Student Life, joined the call for change. Numerous faculty members voiced their support through petitions to the administration. A year later in May 1952, the university’s board approved a resolution to completely desegregate Washington University.

While pushing WU officials to fully desegregate the university, student activists began to look beyond campus. Hoping to attack racial inequality in the larger community, several WU students joined the St. Louis chapter of CORE, which started with fifteen members who met weekly. The WU students joined a racially diverse group of professionals and students from Saint Louis University, Stowe Teachers College, and area high schools, as well. These members organized a campaign of testing restaurants to determine which ones served all customers regardless of race. When restaurants that practiced discrimination were identified, CORE members would attempt to negotiate with their owners, following a pattern established by national CORE leaders. The first step was testing establishments, then negotiating with their owners, and finally, in the most difficult cases, protesting.

Often, business owners would argue that serving Black customers would hurt their business because White customers would not want to eat with Black patrons. CORE used the scheduled tests to show that this was often not the case and that integrating the business would not hurt and might even help. If CORE members could not get the owners to meet or negotiations fell through, then the groups organized sit-ins, boycotts, and stand-ins. While these campaigns occurred, CORE members often continued the negotiation process in hopes of persuading owners to open their establishments to everyone.

The longest and most publicized campaign centered on the weekly (sometimes biweekly) sit-in demonstrations at the first-floor lunch counter in the Stix, Baer and Fuller department store located in downtown St. Louis on Washington Avenue. The protests began in mid-1948 and went on for more than a year.

Despite the longevity of demonstrations and the managers’ reluctance to commit to any policy change, the atmosphere between the employees, customers, and protesters at the lunch counter remained cordial. A 1955 report by the St. Louis CORE chapter reported that while at first Stix, Baer and Fuller employees used various methods to hinder the protests, after a while “they became so used to having us around that they no longer tried to stop or interfere with the ‘sit-downs.’ ” The report went on to discuss how “waitresses even joked with us” and that the managers willingly spoke with the protesters rather than just ignoring their presence.

The CORE campaign at Stix ended in December 1949, but the department store did not change its policy and serve all customers at the lunch counter until six years later.

CORE members also worked to alter policy at other department stores, local drug store chains, national drug store chains, five and dime stores, and restaurants.

In May 1952, a group of thirty Columbia community members, students, and MU and Stephens College faculty petitioned for affiliation with the national CORE organization. Like the St. Louis chapter, the Columbia chapter was not a campus chapter; instead it was a mix of community members and college students. From the start, the group focused on desegregating public places and paid special attention to establishments near campus so that Black students had off-campus restaurant options when campus dining halls were closed.

Similar to St. Louis, Columbia’s CORE had the most trouble getting the discriminatory policies at dime store and drugstore lunch counters changed. While Black customers could shop in the stores, the lunch counter would not serve Black patrons except for takeout. By February 1953, members staged frequent sit-ins at Newberry’s lunch counters, with hopes that the owners would meet for negotiations. Once their tests at Crown Drug Store showed discrimination, they instituted a sit-in campaign there as well.

One commonality among student civil rights organizations is that there were peaks and declines in participation and interest among the transient college community. If there was not a great deal of community participation, then college chapters especially could suffer when the active student membership graduated and left the community.

The Columbia chapter saw a sharp decline in interest during 1954, which led to its disbanding. The Columbia chapter suffered decline in the wake of the landmark Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education, which struck down the “separate but equal” ruling of the Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) case. Merchants and activists alike believed that the court ruling would extend to public accommodations, mitigating the need for direct action, but this was not the case and racial inequality remained pervasive.

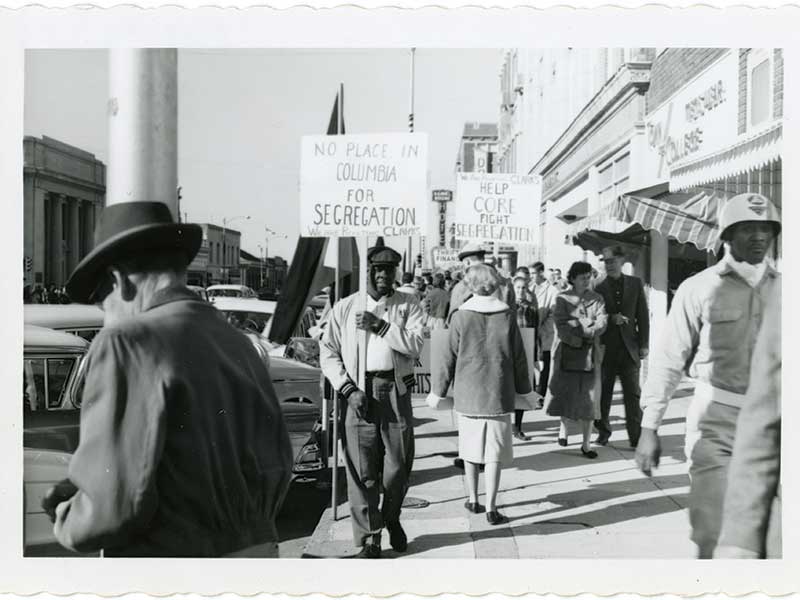

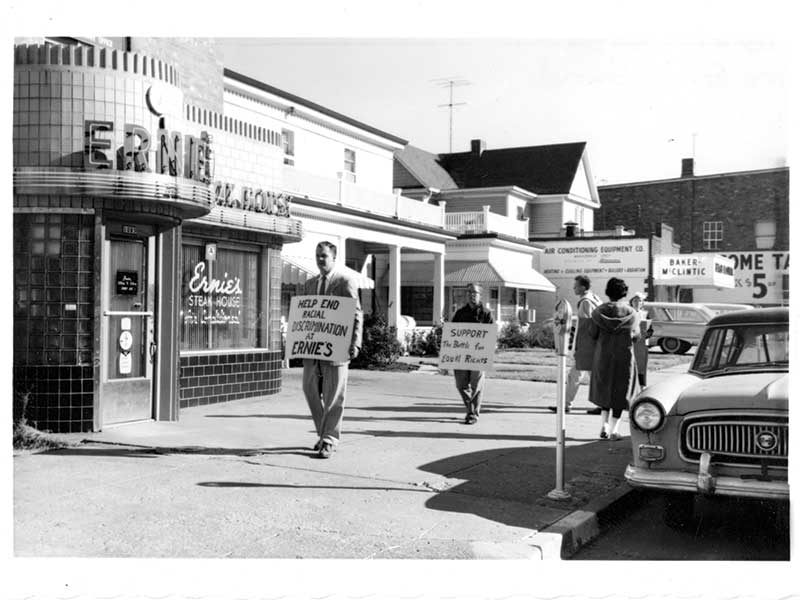

Five years later, a group of MU students organized a boycott of the Tiger Inn, which sat across the street from the Men’s Residence Hall. These students started another iteration of CORE, which affiliated with the national organization in 1960. The new CORE chapter also engaged in sit-in and picketing campaigns, the most visible of these happening during Homecoming Weekend in November 1960. CORE members protested outside of Clark’s Soda Luncheonette on Broadway and Ernie’s Cafe on Walnut because of the continual refusal of both owners to meet with CORE members.

Several times during tests of Clark’s Soda Luncheonette, CORE members were met with violence from the owner or security guards. In February 1963, a group of CORE members was testing Clark’s Soda Luncheonette. If they were refused service, they planned to simply leave. Fred Clark told the CORE members to get out, and then he threw one member, David Keyes, to the floor. Keyes charged Clark with assault, but Clark was found not guilty in May. These two businesses remained segregated until Columbia passed civil rights legislation in June 1964 that prohibited racial discrimination, and this CORE chapter soon disbanded as members thought that local and national legislation would result in change, although there were still battles to wage.

Unlike the Columbia CORE chapter, the St. Louis CORE continued on and thrived in their efforts to tackle job inequality throughout the 1960s.

Although there was a consistent flow of information and occasional visits between the St. Louis and the Columbia CORE chapters, there were not many instances where the two groups worked together on a campaign. One example of cooperation occurred in April 1961 when a group of young men and women, both Black and White, began what they called the Little Freedom Rides. Ten students from MU, one student from Columbia’s Hickman High School, and four students or adults from the St. Louis CORE chapter set out to test dining establishments along the interstate bus line from Illinois into Missouri.

This campaign was influenced by the national organization’s planned Freedom Rides, which began May 4, 1961, and the purpose was to test whether owners adhered to the policy of nondiscrimination in public accommodations along interstate bus lines. The group started in East St. Louis and traveled on the Greyhound bus line toward New Madrid and did not have any problems at stops in Cape Girardeau and Flat River. However, they were faced with opposition in Sikeston when the owner of the Cyrus Restaurant refused to serve the group. When they sat down in protest, the police were called and the activists were arrested for disturbing the peace. No violence occurred towards the protesters, and it is unknown what happened with the charges that were filed. It’s a good example of the students from Columbia and St. Louis coming together to challenge racial inequality.

Into A New Century

MU students continued their efforts to improve race relations on campus and in the larger community. In 1968, Black students at MU formed the first Black student government in the country—known as The Legion of Black Collegians (LBC). Most other colleges have a Black Student Union or Alliance, but the LBC remains the only Black student government in the country. Its mission included representation of Black students on campus and efforts “to end discrimination within the campus community.” Through the issuance of demands to university administration, LBC successfully pushed for more funding and involvement for Black students in campus activities, the hiring of more Black faculty and staff, and the creation of a Black Studies program.

The LBC was formed in response to a now-defunct tradition of playing “Dixie” and waving a Confederate flag at football games. The organization was formed in 1968 and recognized by MU in 1969.

In 1974, along with CORE members, the LBC also worked with the Missouri Students Association (MSA) to push for removal of Confederate Rock from its location on campus at the corner of Ninth and Conley. The rock is a five-and-a-half-ton granite rock meant to honor Boone County’s Confederate soldiers. After students pushed for its removal, it was relocated to the Boone County Courthouse in 1975. In 2015, Boone County Commissioners again voted to move the rock, this time to the Battle of Centralia Historic Site, after an MU alumnus named Tommy Thomas III submitted a petition for its removal.

During the 2015–2016 protests at MU, students in Concerned Student 1950 (CS1950), an activist group whose name is a nod to the fact that MU did not admit its first Black student until 1950, issued demands to university administrators. Among their demands, CS1950 included the original list of demands issued by the LBC in the late 1960s and throughout the 1970s, which was meant to illustrate the continued need for change. The protests resulted in key demands met, including the resignation of top officials.

For the first time in its nearly two-hundred-year history, Missouri elected a Black woman, Cori Bush, as a US Congressional Representative in last November’s election. Bush worked as a nurse in St. Louis before being elected to US Congress, and her foray into politics began with the 2014 protests in Ferguson. Before her, Emmanuel Cleaver became the first Black man elected by Missourians to the US House of Representatives in 2004.

The landscape of the state has changed a good deal since its inception, a time when slavery was not only legal but flourishing here. The legacy of those who stood up for equality throughout our past has long pointed the way toward a more just future where, as our state motto dictates, the welfare of the people may serve as the supreme law.

Photos // State Historical Society of Missouri, St. Louis Mercantile Library at University of Missouri-St. Louis, St. Louis Post-Dispatch

Related Posts

STATE-TISTICS: January/February 2020

Missouri's alcohol consumption by the numbers.

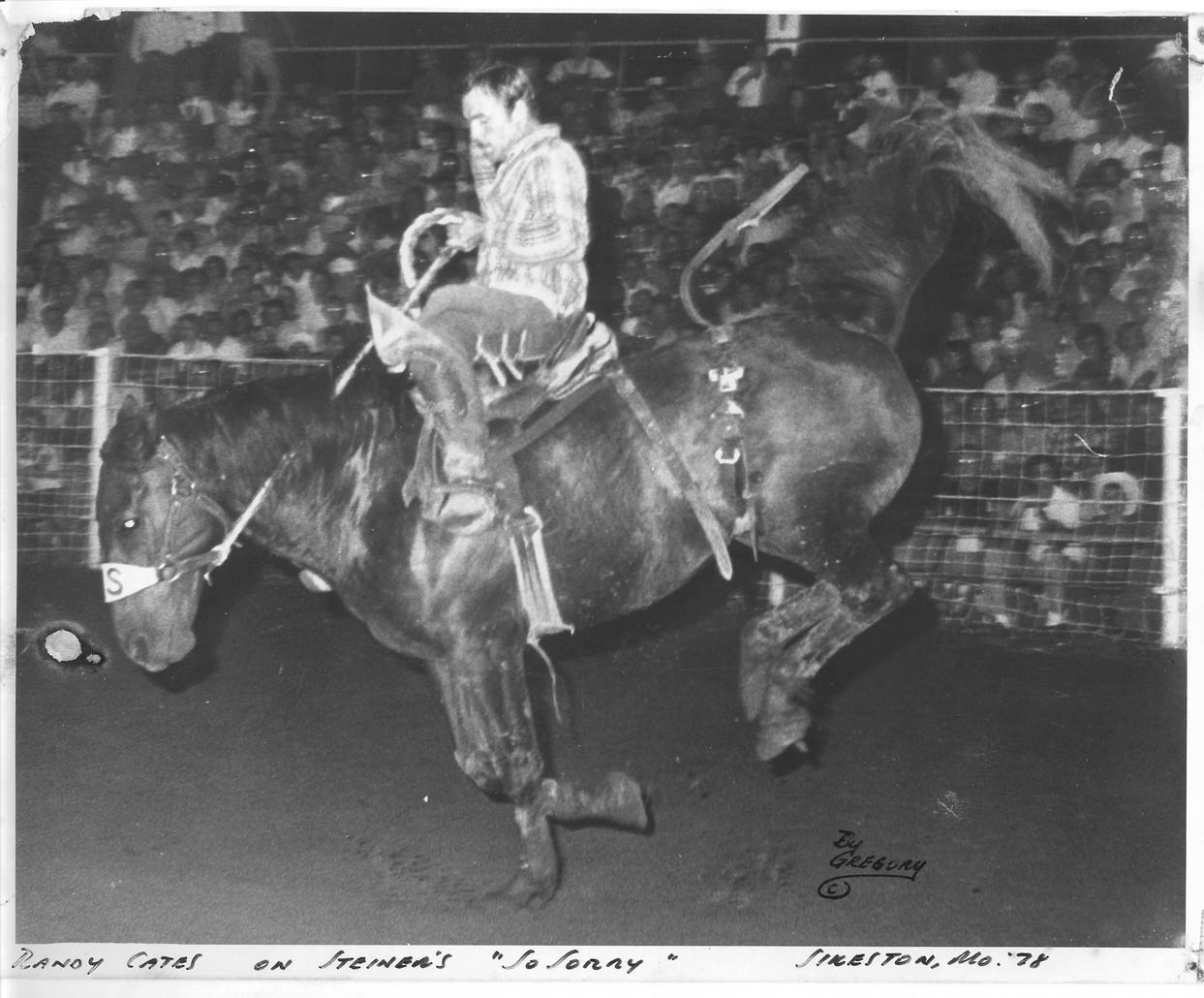

The Ballad of Randy Cate: Show-Me State Cowboy

Cowboy Randy Cate garners the Chester A. Reynolds award for a life spent on horseback.