This is the sixth story out of nine in a series dedicated to Missouri’s Bicentennial. Read the rest here: one, two, three, four, five, seven, eight, nine.

Story by Philip Howerton.

Most Missourians are aware that Mark Twain, considered by many to be the greatest American storyteller of all time, was born and raised in the Show-Me State. Aside from Twain, Missouri has produced the likes of Tennessee Williams, T. S. Eliot, Kate Chopin, and Maya Angelou, among countless others whose names can be found in the canon of American literature. Although we can be proud of Missouri’s impact on writing, we may not always be as apt to consider the writing that has impacted Missouri. The way various authors have chosen to represent our state shapes the way readers perceive it, from those of us who grew up here to people who’ve never stepped foot inside our borders. In honor of the Bicentennial, we asked Dr. Phillip Howerton, professor of English at Missouri State University and editor of The Literature of the Ozarks: An Anthology, to explore ten literary works that have shaped our state.

John Bradbury, Travels in the Interior of America in the Years 1809, 1810, and 1811

John Bradbury explored the Missouri River Valley in 1811 and published his record of this trip as part of Travels in the Interior of America in 1817. Bradbury was born in England in 1768, studied botany, and was sent by a Liverpool botany society to the United States to collect plant specimens and to investigate possibilities for enhancing cotton exportation to Britain. Bradbury joined the Pacific Fur Company expedition and left St. Charles in mid-March. He exited the future state of Missouri approximately five weeks later.

Bradbury’s account of his observations in Missouri runs less than forty pages, but every page is alive with detail. He dates each entry and mentions streams, landmarks, and villages, which allow modern readers to easily map his progress. He provides much of what is expected in a travel narrative, such as adventure, cultural differences, and descriptions of nature. He interviews the elderly Daniel Boone, notes the indolence of many settlers, offers sketches of Native Americans, and reports the sublimity of nature and how it is threatened by settlement. He is saddened after being forced to kill a bear protecting her infant cubs, but he later shoots almost three hundred passenger pigeons for mindless sport. At several points in the narrative, he states that he is moving beyond civilization and entering wilderness, but he soon encounters yet another outpost of expanding civilization.

This brief account introduces themes and descriptors that continue to define rural Missouri. Bradbury described an accessible frontier that offered a sense of cultural clash, visions of wilderness, and a sense of escape. These themes, and the negative and positive descriptions that accompany them, appear in much of Missouri’s literature—and are apparent in movies, television shows, and documentaries depicting the state.

Lanford Wilson, Talley’s Folly

Talley’s Folly is the second in a trilogy of plays exploring the impact of war and economic instability upon the Talley family. This one-act play of ninety-seven minutes has one scene and only two characters. It is set on July 4, 1944, at the Talley farm near Lebanon, Missouri, the town where Lanford Wilson was born in 1937. Talley’s Folly was performed on Broadway almost three hundred times and was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in 1980.

The play opens with one of the characters, Matt Friedman, speaking directly to the audience to explain that he has arrived uninvited from St. Louis to propose marriage to Sally Talley, whom he has not seen for a year and who has discouraged his romantic interest. Although it is a romantic comedy laced with flippant humor, the play explores how a variety of social and cultural forces destroy human personality and happiness. Matt and Sally banter and argue but eventually force one another to reveal their deepest secrets. Matt is Jewish, and he admits that he was probably born in Lithuania, that members of his family had been detained and tortured in Europe shortly before World War I, and that he has vowed never to have children. Sally reveals that her family, a prominent family that owns a garment factory, had groomed her to marry into another successful business family. When an illness rendered her incapable of having children, the marriage deal was cancelled. Matt and Sally are left to contemplate what happiness means to each of them and how their lives will look in the future.

As this play suggests, regardless of how remote folklore and popular media have depicted the region, rural Missouri has never been isolated from the larger world. World events touch the Talley home front: the Depression has threatened the Talley’s garment factory and a refugee from the ruins of Europe arrives at the farm attempting to take away their once-prized daughter. Wilson also plays with some common Ozarks stereotypes as Matt mimics the Talley’s hill accent, teasingly suggests the family maintains a still, and claims Sally’s brother ran him off with a shotgun.

William Wells Brown, Narrative of William Wells Brown, a Fugitive Slave

Narrative of William Wells Brown, a Fugitive Slave, Written by Himself was first published in 1847 and underwent three more printings before 1850. Although Brown was born in Kentucky in 1814, he spent most of his first twenty years in the vicinity of St. Louis. He was a house servant, a field hand, and a servant in a tavern and in a newspaper office, and he also served a slave trader. These varied experiences provided him a broad and deep understanding of slavery.

Brown is an immensely important figure in American literature, and his Narrative is a seminal text, included in the Norton Anthology of American Literature and routinely taught in American Literature courses. He experimented with almost every literary genre, and he is often credited with authoring the first travel book, novel, drama, and military history published by an African American. This autobiography narrates the expected stages of Brown’s transition from a slave unaware of his condition to a free man aware of the full evils of slavery, yet he makes it original and moving by delivering an objective and unadorned narrative. His goal is to expose the vicious reality of slavery, and he becomes a voice for the millions in bondage by refusing to celebrate himself or to set himself apart.

Although slavery is synonymous with the Antebellum South, Brown challenges the notion that it was any less cruel north of the Mason-Dixon by stating “no part of our slaveholding country is more noted for the barbarity of its inhabitants than St. Louis,” and he then provides several vivid examples. He further incriminates this section of the state by pointing out that it produced a steady supply of slaves to the Deep South. Brown’s account demonstrates the value of history and memory. We must confront and remember the unspeakable horrors that humans are capable of unleashing upon one another. Perhaps the most dehumanizing act that the living can perform upon the dead is to forget.

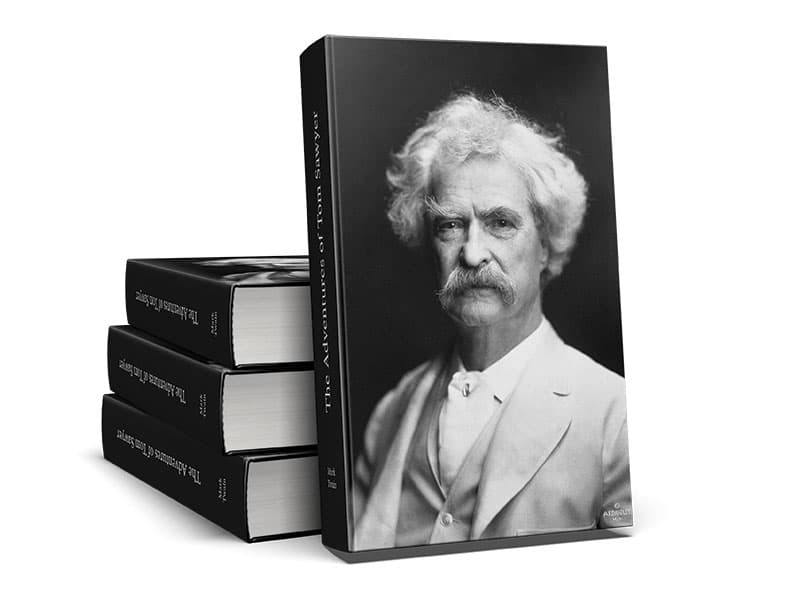

Mark Twain, The Adventures of Tom Sawyer

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer was published in 1876 and has been second only to Huckleberry Finn in popularity within the massive oeuvre of Mark Twain. Although often dismissed as a children’s book, several of its scenes, such as Tom and Becky being lost in a cave and the whitewashing of the fence, serve as representative images of Missouri to people everywhere.

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer was published in 1876 and has been second only to Huckleberry Finn in popularity within the massive oeuvre of Mark Twain. Although often dismissed as a children’s book, several of its scenes, such as Tom and Becky being lost in a cave and the whitewashing of the fence, serve as representative images of Missouri to people everywhere.

Tom Sawyer has been much less controversial than Huckleberry Finn, yet this novel has had its share of critics. Initially the book was attacked because it appeared to praise Tom’s mischievous behavior; apparently, the good-hearted and often noble lad was setting a poor example by pulling pranks, playing robber, and hanging out with the ruffian Huck Finn. Through the years, numerous readers have noted that Twain, in his attempt to appeal to children and adults, fails to balance the antics of Tom with the book’s formal language. Recently, some critics have noted the racist and dismissive characterization of Injun Joe.

Perhaps the greatest challenge to Tom Sawyer’s future is that the childhood it depicts is far removed from today’s typical childhood. Few young readers will identify with such old-fashioned fun as playing with a pinch bug or burying a dead cat in a graveyard. The Hannibal of Twain’s youth offered a splendid playground and seedbed for his imagination—the Mississippi River, McDougal’s Cave, Jackson’s Island, Cardiff Hill, a haunted house, and a buried treasure. In turn, Twain reproduced for readers something that all children should experience and something that should never fall out of fashion—a childhood that is a joy to recall.

Harold Bell Wright, The Shepherd of the Hills

Harold Bell Wright was born in 1872, in Rome, New York, and accidentally became a preacher when invited by a congregation to read one of his novels as a sermon. Ill health forced Wright to step down from preaching, but he continued his ministry through fiction. His novels, although scorned by literary critics, were exceedingly popular; several sold more than a million copies. The Shepherd of the Hills remains the most influential Missouri novel.

Harold Bell Wright was born in 1872, in Rome, New York, and accidentally became a preacher when invited by a congregation to read one of his novels as a sermon. Ill health forced Wright to step down from preaching, but he continued his ministry through fiction. His novels, although scorned by literary critics, were exceedingly popular; several sold more than a million copies. The Shepherd of the Hills remains the most influential Missouri novel.

In this moralistic tale, a prominent preacher abandons his career in Chicago and comes to the Ozarks seeking physical and spiritual renewal. Immediately trusted and loved by the hill people, he becomes the religious leader of his adopted community even as he realizes the devastating impact some of his past decisions have had upon his new friends. The peace he is seeking is also disrupted by ghosts and night-riding vigilantes. The Shepherd of the Hills was largely responsible for the commercial development of Missouri’s White River Valley, once known as Shepherd of the Hills Country. Readers of Wright’s novel flocked to the region to visit the paths walked by his characters—especially Sammy Lane and Young Matt—and embrace the restorative powers of the Ozark hills. The book’s success also spawned numerous other Ozarks-based novels in the pastoral vein.

At times Wright’s sermon feels too heavy-handed, and there are several moments when he is forced to drop in yet another coincidence or contrivance to salvage his plot or to save a hero. However, his detailed and imagistic descriptions are some of the finest in Ozarks literature, and he is a master at creating suspense. If we ignore his literary shortcomings, we might see that Wright’s lesson of forgiveness has more value now than ever.

Jack Conroy, The Disinherited

Jack Conroy was born in 1899 in the coal mining country near Moberly, and he experienced much of what is depicted in The Disinherited, including the deaths of his father and two brothers in the local coal mine. The protagonist narrates his boyhood in the mining camp, his years as an itinerant worker during World War I and the 1920s, and his life after his return to Missouri in the years shortly before the book was published in 1933.

Jack Conroy was born in 1899 in the coal mining country near Moberly, and he experienced much of what is depicted in The Disinherited, including the deaths of his father and two brothers in the local coal mine. The protagonist narrates his boyhood in the mining camp, his years as an itinerant worker during World War I and the 1920s, and his life after his return to Missouri in the years shortly before the book was published in 1933.

Written by a worker who transformed himself into a writer and remained a worker, The Disinherited shows the exploitation of the laboring class, argues a better system must be found, and urges workers to unite to protect themselves. Conroy refuses, however, to become the mouthpiece for abstract economic theories, and thereby saves this novel from degenerating into mere propaganda. Unlike many of the justly forgotten proletarian novels of the 1930s, The Disinherited remains focused on the experiences and reactions of individuals. Conroy does not sacrifice the humanity of his characters for an ideology. Because he lived most of these experiences and performed much of the labor he depicts, Conroy is able to deliver convincing and detailed renderings of numerous dangerous and gut-twisting jobs.

The novel has several flaws: it has no plot, its narrative is often disjointed and jarring, there are several coincidences, and some passages appear to be formulaic moral scenes. But The Disinherited rings with authenticity, and it reminds us that much of the essential and dirtiest labor and the people who perform it often remain invisible. It makes some of this labor and the laborers of the past visible.

Josephine W. Johnson, Now in November

Now in November was Josephine W. Johnson’s first novel. Published in fall 1934, it was awarded the Pulitzer Prize the next year. Johnson was only twenty-four at the time, and she remains the youngest person to win a Pulitzer for fiction. She was born in Kirkwood and wrote much of the novel at her mother’s farmhouse in Webster Groves. The novel, through the character of a teenage girl, tells the story of a family struggling to survive on a mortgaged farm during the Great Depression and Dust Bowl.

Now in November was Josephine W. Johnson’s first novel. Published in fall 1934, it was awarded the Pulitzer Prize the next year. Johnson was only twenty-four at the time, and she remains the youngest person to win a Pulitzer for fiction. She was born in Kirkwood and wrote much of the novel at her mother’s farmhouse in Webster Groves. The novel, through the character of a teenage girl, tells the story of a family struggling to survive on a mortgaged farm during the Great Depression and Dust Bowl.

The plight of small, independent farmers during the years of depression and drought has received limited study, and Now in November provides insight into this life. This family falls from a middle-class, small-town lifestyle and returns to the poverty of their farm. This land may have once been a safety net, but now it is a net that ensnares them. Johnson challenges the common view that farmers enjoyed a level of security during the Depression because they could feed themselves. But a mortgaged farm produces more debt than income during drought, and mortgages and taxes must be paid with dollars. These farmers had to do the impossible—to earn a profit during economic collapse and drought—or be forced off the land that was their food source.

Johnson also deepens the picture of Missouri farm life by delivering the story through a girl on the verge of adulthood. It is nearing time for the protagonist to choose a future, but there appears to be no future to choose. As a female living in the 1930s, she would have had limited opportunities even during the best of economic conditions, but she is coming of age during economic collapse. Nature is her only solace, but its small symbols of beauty and hope become ever rarer as the drought deepens.

Ward Allison Dorrance, Three Ozarks Streams

Ward Allison Dorrance was born in Jefferson City in 1904 and earned a bachelor’s, master’s, and a doctorate from the University of Missouri at Columbia. Dorrance began teaching French at the university in 1926 and continued to teach there until 1953; he then taught at Georgetown from 1958 to 1974. In his first book, Three Ozarks Streams, published in 1937, Dorrance records his experiences of floating three rivers in the southeastern Missouri Ozarks: the Black, the Current, and the Jack’s Fork.

Many nature writers have been favorably compared to Henry David Thoreau, but few have deserved that honor. Dorrance does; he rivals Thoreau with his power to capture nature’s sublimity in taut, resounding phrases. For example, Dorrance describes the river’s V-shaped currents as “the overlapping blue muscles of water,” the sound of a nearby bullfrog as “the voice of one who has entered the room unseen,” and rain water as tasting like “the space through which it has fallen.” Such descriptions offer readers the essence of the natural setting while avoiding the clichéd praises of nature found in much early Ozarks travel prose.

Unlike many writers exploring the Missouri Ozarks, Dorrance refuses to cast himself as a superior outsider among inferior residents. Dorrance admits his lack of outdoor skills several times, and although he is amused by elements of Ozarks culture, he is intrigued rather than contemptuous. He seems to admire the descriptive power of hill speech as much as he does the like powers of Native-American languages and French, and throughout this travel log, Dorrance portrays the Ozarks people as friendly, intelligent, and endearing.

Henry Bellamann, Kings Row

Heinrich (Henry) Hauer Bellamann was born in Fulton in 1882, and he graduated from Fulton High School and attended Westminster College for a year before moving to Colorado in 1901. His best-selling novel Kings Row was published in 1940. Kings Row is Bellamann’s fictional name for Fulton, and in the novel he expressed resentment for his hometown, a resentment that apparently was the result of the ostracization that he had experienced due to his German extraction and rumors of his illegitimate birth. The novel is perhaps best remembered today for the film version it spawned in 1942 starring Ronald Reagan.

Heinrich (Henry) Hauer Bellamann was born in Fulton in 1882, and he graduated from Fulton High School and attended Westminster College for a year before moving to Colorado in 1901. His best-selling novel Kings Row was published in 1940. Kings Row is Bellamann’s fictional name for Fulton, and in the novel he expressed resentment for his hometown, a resentment that apparently was the result of the ostracization that he had experienced due to his German extraction and rumors of his illegitimate birth. The novel is perhaps best remembered today for the film version it spawned in 1942 starring Ronald Reagan.

Kings Row tells the story of Parris Mitchell, a young man who grows up in Kings Row, moves to Europe to study medicine, and then returns to serve as a psychiatrist in the town’s asylum. During his early years in the town and while he was abroad, he learns several of his hometown’s gothic and morbid secrets, including cases of incest, murder, suicide, mental illness, and revenge amputations. Parris and Kings Row grow and change, and by the end of the novel, Parris has worked to remedy several problems in Kings Row and is becoming a pillar of the community. The young man who escaped his hometown has now become one of its saviors.

Most critics agree that Bellamann introduces far too many characters, that many of them are unoriginal and underdeveloped, and that he had too many themes and too much plot for one book. Yet such incompleteness is reality, for most communities contain far more people and relationships and social forces than we can comprehend or describe. Parris recognizes the continual evolution of this place and then attempts to influence its evolution in a positive manner.

John Williams, Stoner

Stoner was first published in 1965 by Viking Press and sold only about two thousand copies. This novel tells the life story of William Stoner, a farm boy from near Boonville, who earns degrees from the University of Missouri at Columbia and then spends the rest of his life teaching there. The novel was reissued by various publishers and has slowly and quietly become one of the most popular and critically acclaimed Missouri-based novels. John Williams was born in 1922 and received his doctorate in English from MU in 1954.

Stoner was first published in 1965 by Viking Press and sold only about two thousand copies. This novel tells the life story of William Stoner, a farm boy from near Boonville, who earns degrees from the University of Missouri at Columbia and then spends the rest of his life teaching there. The novel was reissued by various publishers and has slowly and quietly become one of the most popular and critically acclaimed Missouri-based novels. John Williams was born in 1922 and received his doctorate in English from MU in 1954.

The central theme in this novel is heroism, and in this case, the heroism of an individual who finds identity and value in his work. Some critics have argued that the character is a failure and that he never rises above the rank of assistant professor, has an undistinguished career that is nearly destroyed by department politics, spends all his adult years in an unfulfilling marriage, and has a strained relationship with his only child. But Stoner is an existential hero who recognizes that he must create his own happiness and purpose, and he ceases to work only upon his death. He then accepts death without fear and without complaint, knowing he has left a little of himself in the work he has performed, and he exits before he becomes a burden for others.

Stoner and his parents are Missouri farm people, and in the opening chapters they appear defeated, unimaginative, uncultured, and socially awkward. As the narrative moves forward, however, a more nuanced picture of them emerges as they confront challenges and change. Stoner’s work ethic and patience result in academic success, and Stoner’s parents are forbearing and accepting. When Stoner announces that he will not be returning to the farm, they make no demands on his future and quietly release him, and it is some moments before Stoner realizes that his mother “was crying, deeply and silently.”

Related Posts

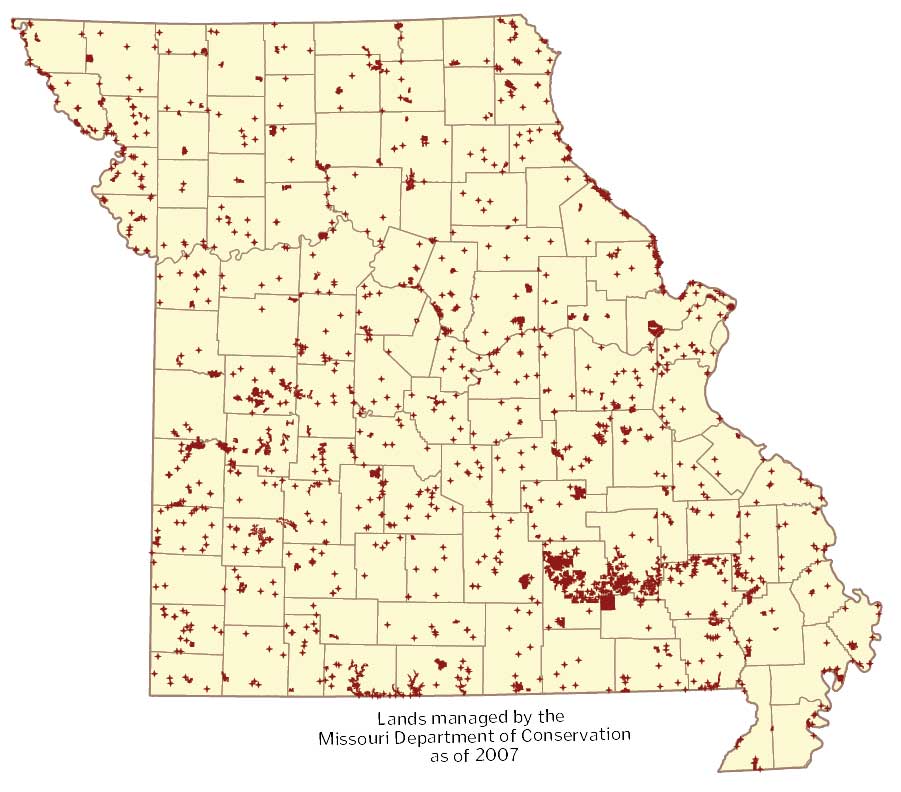

STATE-TISTICS: Conservation Areas in Missouri

Conservation areas by the numbers

10 Books on Missouri’s Native American History

Looking for more reading on the Osage and Missouria tribes? Parts 2 and 3 of our special series are forthcoming in September and October, but in the mean time we highly recommend this selection of books that cover the subject.