This is the first story out of nine in a series dedicated to Missouri’s Bicentennial. Read the rest here: two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight, nine.

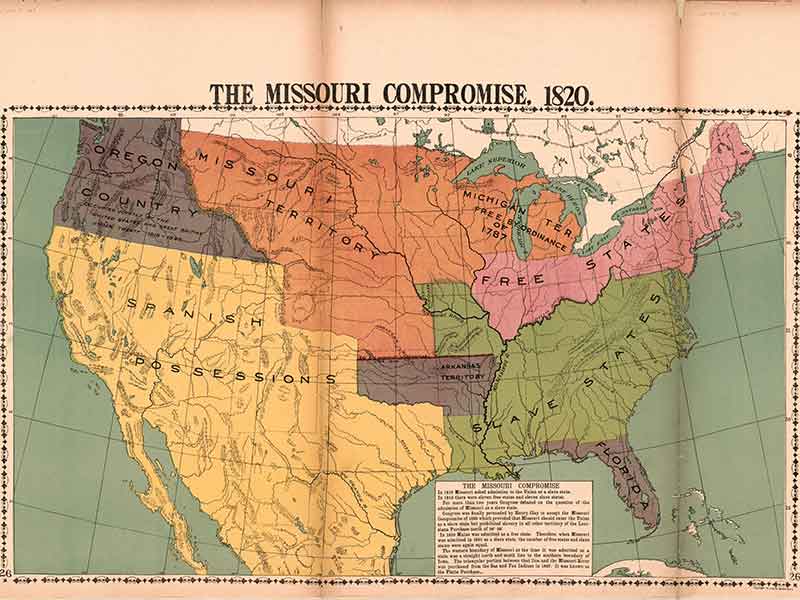

Could we Missourians actually unwittingly bypass our bicentennial celebration? Peruse any history textbook, or any website about the history of states entering the Union, and each and every one will declare Missouri’s admission date as August 10, 1821, but could that date actually be wrong? Why don’t we look to March 6, 1820, as the real admission date for our state? After all, that is when President James Monroe signed the Missouri Bill, which passed Congress in one of the most tumultuous and contentious debates in American history. This new act authorized Missourians to commence the process for statehood, that is, to adopt a state constitution and establish a state government, which they did over the summer of 1820. So why is our official bicentennial date in August of 2021 and not this March?

Well, it’s complicated, but we can begin with the undisputed fact that no state ever entered the Union with as much divisiveness, bitterness, and utter turmoil than we did. In fact, some Americans went so far as to call for civil war right then—rather than admit Missouri into the family of states.

Our territory had already come a long way in a short period of time when we entered the Union as the twenty-fourth state—whenever that officially occurred. We became the first state situated entirely west of the Mississippi River and the second to come out of the 1803 Louisiana Purchase. (Louisiana was the first state to come out of that territory but has a section east of the Mississippi River.)

In 1808, the government bought fifty-two million acres of the Osage tribe’s original homeland, in return for a pitiful .005 cents an acre. At the end of the War of 1812, in 1815, another ten tribes affirmed US ownership of Missouri in the Treaty of Portage des Sioux. In less than three years, the first petitions requesting statehood arrived at the nation’s capital.

So, the quest for statehood officially commenced on January 8, 1818, one of the most revered dates in American history at that time, for January 8, 1815, was the final battle of New Orleans, which Americans would proudly celebrate for decades to come, even more than the Fourth of July.

What a coincidence, then, that one of the most propitious days in our history was also a day that began the struggle to allow Missouri a white star on the blue canton of the Stars and Stripes. While one event, the Battle of New Orleans, saved the American Union, the other event, the presentation of petitions from Missouri requesting admission into the Union, turned up the heat in the brewing conflict that four decades later would boil over, tearing apart that American Union.

The first hint that Missouri’s statehood would erupt in fierce controversy came in the US House on April 9, 1818, when an obscure New Hampshire congressman proposed a constitutional amendment prohibiting slavery in any state thereafter admitted into the Union. More petitions and memorials (informal diplomatic papers) from Missouri arrived in Washington that spring, but Congress refused to act on either the amendment or the petitions.

The Road to Statehood Timeline

1803: Thomas Jefferson acquires the Louisiana Territory.

1804: Congress divides the territory into two, The Territory of Orleans and The District of Louisiana; the future Missouri lies within the latter.

1805: The District of Louisiana becomes the Territory of Louisiana.

1808: The Unites States purchases fifty-two million acres from the Osage.

1812: War breaks out with Great Britain, and the Territory of Louisiana is renamed Territory of Missouri.

1815: The Treaty of Portage des Sioux affirms US ownership of the remaining land that became Missouri.

1818:

January 8

Missouri presents petitions requesting admission into the Union.

April 9

A constitutional amendment is proposed prohibiting slavery in any state thereafter admitted into the Union.

December 18

Congressman Henry Clay petitions for Missouri to adopt a constitution and establish a state government.

1819:

February 13

Congress commences debate on the Missouri Bill and Congressman James Tallmadge proposes an amendment prohibiting further introduction of slavery into the state, except for the punishment of crimes, and that all children of slaves would eventually be freed.

March 3

Congress adjourns with no settlement of the issues.

December 14

Representative John W. Taylor of New York introduces his resolution restricting slavery in territories. The petition from Maine for admission becomes linked to Missouri’s admission.

1820:

March 2

The House finally passes the Senate version, with a Thomas Amendment allowing slavery in Missouri but prohibiting it above thirty-six degrees, thirty minutes, or the southern border of Missouri, in remaining territories.

March 3

President James Monroe convenes his cabinet to discuss the Missouri question.

March 6

President James Monroe signs the Missouri Bill.

May

Missouri counties elect delegates to Missouri first constitutional convention.

1820:

July 19

The state constitution was adopted.

September 18

The first state legislature convenes in St. Louis.

November 16

The US Congress refuses to seat Missouri delegates because of a clause in the state constitution prohibiting Negroes or mulattoes from coming to and settling in the state.

1821:

February 26–28

The Eaton Provisio passes both houses of the US Congress to deal with the potential conflict of the state constitution with the US Constitution.

June 26

The Missouri legislature passes the Solemn Public Act promising not to pass future legislation conflicting with the US Constitution.

August 10

President Monroe pronounces Missouri is now admitted to the Union, and this became our official statehood date

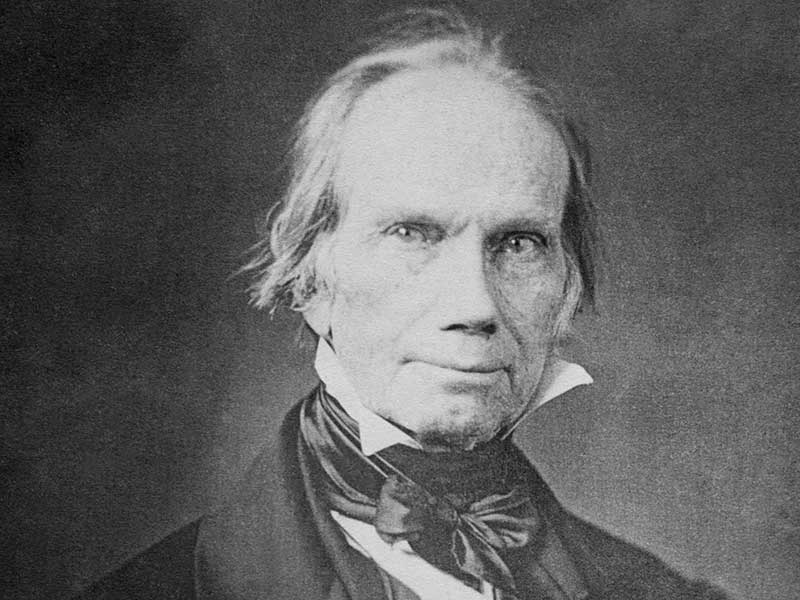

The great struggle renewed in the next session of Congress, on December 18, 1818, when Kentucky’s Henry Clay introduced in the US House an official memorial from Missouri asking for permission to adopt a constitution and establish a state government. At the same time, a national antislavery convention, representing nearly every state antislavery society in the country, convened in Philadelphia and likewise issued an official memorial to Congress—demanding the prohibition of slavery in every US territory and any state admitted from said territories. This obviously applied to Missouri.

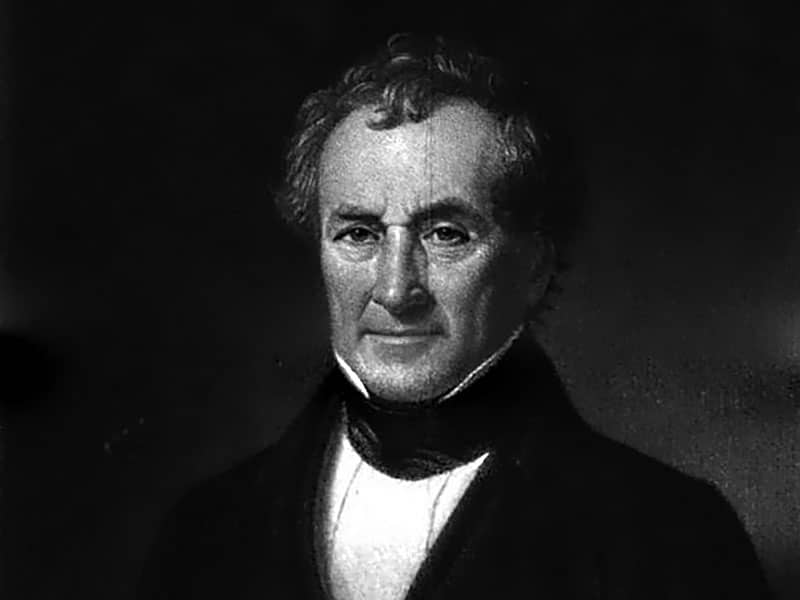

On February 13, 1819, Congress finally commenced debate on the Missouri Bill (and a bill for Alabama’s admission as well, although no controversy occurred as it was already established slave territory).

On that same day, James Tallmadge, a New York representative in the House, proposed an amendment to the Missouri Bill. It read, “That the further introduction of slavery or involuntary servitude be prohibited, except for the punishment of crimes, whereof the party shall be duly convicted; and that all children of slaves, born within the said state, after the admission thereof into the Union, shall be free, but may be held to service until the age of twenty-

five years.”

With this sine qua non for Missouri’s statehood, Tallmadge and his supporters in the US House had instantly transformed the previously routine business of admitting a new state into a volatile dispute that threatened the course of the American Union. The Tallmadge Amendment officially initiated the Missouri Crisis.

The question of the day was simple on the surface: did Congress possess the authority to require conditions, in this instance, a restriction on the expansion of slavery in Missouri, on a territory before it would be admitted into the Union?

To prove the point, for or against slavery restriction, nearly every article and section of the Constitution came under scrutiny, with little if any agreement from opposing sides. Few congressmen could deny that Missouri’s admission raised a plethora of constitutional questions of the highest order. Not since the ratification debates of 1787–1788 had Americans so intensely scoured the Constitution and reconsidered its numerous sections. The Missouri question was, at its core, a constitutional question.

Throughout the intense debate consuming Congress during the late winter and early spring of 1819, the House consistently attached the Tallmadge Amendment to any Missouri Enabling Bill that passed, always barely and along strongly sectional lines, although some northerners supported the slave states. The US Senate as consistently rejected any House bill with the Tallmadge Amendment added—22–16 on the first clause, and 31–7 against the second clause of the fateful amendment. When Congress adjourned in March 1819, they had not settled the Missouri Bill, to the utter consternation of Missourians.

Slave Numbers

In 1819, the territory of Missouri had about the same number of African Americans, ten thousand, as did the state of New York, home of three of the most vocal opponents of the expansion of slavery in Missouri: Congressmen James Tallmadge and John W. Taylor and US Senator Rufus King. Missouri’s enslaved population represented almost 16 percent of the total population of its territory, about the same percentage as New York’s slave population at the beginning of the American Revolution.

Extensive debate ensued nationwide. When the next Congress convened, in December of 1819, petitions flooded that body against the extension of slavery into Missouri. Numerous state legislatures had likewise issued their solemn declarations, for and against restriction.

Although the foundation of the debate was constitutional in nature, regarding congressional authority to place restrictions or conditions for admission into the Union, the expansion of slavery lurked beneath the constitutional question.

A few New England congressmen outright assailed the evils of slavery and called for its quick demise; a few southern congressmen, for the first time publicly in our nation’s short history, hinted that the institution was actually a positive good, for both the African and the white American, and no longer a necessary evil. Some even resorted to the Bible to defend the existence of slavery since time immemorial; others looked to classical and recent republics that practiced slavery.

However, most of their comrades, for and against restriction, called for reasoned reflection. The authors of the numerous petitions opposing slavery expansion in Missouri, streaming into Congress in 1819 and into 1820, for example, made it a point to avoid blaming southerners for the introduction of slavery in the United States (that was clearly the fault of the British) and to assure slave owners that they were not advocating for the abolition of slavery where it currently existed. But the expansion of this most detested practice must not advance west of the Mississippi River, they proclaimed. Unfortunately, the institution was alive and well already in the Missouri Territory, and it existed in the region before the American purchase in 1803.

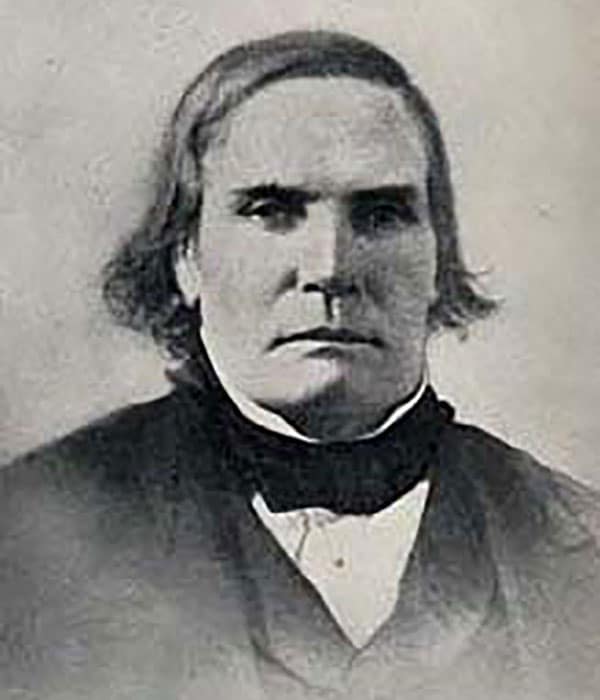

By the time Congress reconvened in December of 1819, the situation had changed. The Maine District of Massachusetts sought admission into the Union as well (as a free state, although the representative in Congress for Maine ardently and actively supported Missouri’s cause to enter without any restriction on slavery). Petitions from Missouri continued to pour in, too. Compromise appeared out of the question. New York congressman John W. Taylor became the new leader of the pro-restriction forces in the House because Tallmadge had resigned from Congress at the end of the previous session, the very session when he had introduced his controversial amendment to the Missouri Enabling Bill.

Taylor formed a House committee to attempt resolution, but it failed in less than two weeks. For that matter, during the entire Missouri Crisis, congressmen introduced dozens of various compromises, all to be promptly dismissed in favor of the original Tallmadge Amendment.

As the new year dawned in 1820, the House passed the Maine Enabling Bill and sent it to the Senate, where that body added an amendment admitting Missouri without slavery restriction. The Senate had united the Maine and Missouri bills by a vote of 32–21.

But then, matters changed again when Illinois Senator Jesse B. Thomas proposed allowing slavery in Missouri but prohibiting it in the unorganized area of the Louisiana Purchase north of thirty-six degrees, thirty minutes (the southern border of the proposed State of Missouri). In February of 1820, the Senate passed the Maine-Missouri Bill with the Thomas Amendment, by a vote of 34–10. The House categorically rejected the Senate bill, dismissing the Thomas Amendment by a vote of 159–18, and passed its own bill with the Tallmadge Amendment.

Status of Free Black People

The Missouri Crisis hastened the deterioration in the status of free black people in some northern states. In 1821, with the final admission of Missouri into the Union, the New Jersey supreme court declared that “black men are prima facie slaves,” and in 1826 announced it to be a “settled rule” that “black color is the proof of slavery.” The eradication of slavery in New Jersey proceeded at a slower pace than in any other free state.

Illinois’s Black Codes

During the debates over the admission of Illinois into the Union, in December of 1818, New York Congressman James Tallmadge opposed Illinois’s admission because its constitution did not sufficiently prohibit slavery. The Illinois state constitution permitted limited slavery at the salt mines in Massac County, and it legalized the continued bondage of slaves introduced by the French, although it also included a provision that declared that the children of those slaves were to be freed when they reached adulthood, women at eighteen and men at twenty-one.

Following statehood, the Illinois state legislature enacted one of the harshest Black Codes in the Union, designed to discourage black people from coming to Illinois. Free black people were denied suffrage and could not testify in court or serve in the militia. Black people assembling in groups of three or more could be jailed and flogged. State law also forbade slaveholders, under penalty of severe fine, from freeing their slaves. Legislators intended to discourage Illinois from becoming a haven for runaway slaves. Any runaway found in the state could be sentenced by a justice of the peace to thirty-five lashes.

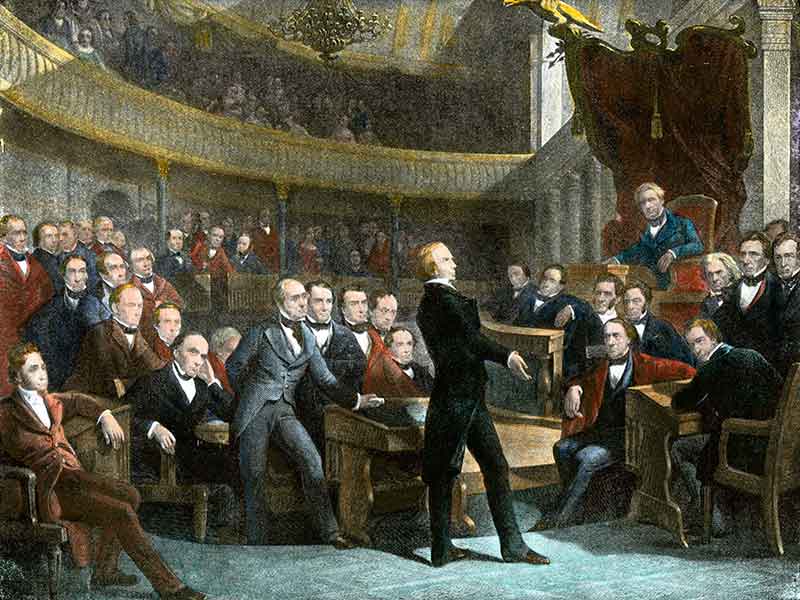

Enter powerful Henry Clay. The Kentucky congressman created a conference committee to break the deadlock and admit Missouri. He persuaded the House to accept the Senate’s version—with the Thomas Amendment and not the Tallmadge Amendment—which it did on March 2, 1820. The crucial vote in the House, to strike the provision prohibiting slavery in Missouri, squeaked by the House, by just three votes, but the approval of the Thomas Amendment, again a testament to the power and influence of Henry Clay, cruised by with a vote of 134–42. Maine entered the Union in a separate bill, while Missouri’s bill authorized the people there to draw up a constitution and form a state government.

Case closed—or so Missourians thought, as they expected President James Monroe to sign the bill. But a new round of debate would involve an already chafed Missouri.

Though the admission of Missouri was ultimately a legislative question, President Monroe had worked behind the scenes to achieve a compromise. Monroe believed that a state must be admitted on an equal footing with existing states and that any condition for admission not applicable to older states violated Missouri’s constitutional rights and sovereignty.

Furthermore, Monroe recommended that Maine be admitted separately from any settlement regarding Missouri, and he approved of the thirty-six degrees, thirty minutes divide for the remaining territories.

After Congress passed the compromise bill with the Taylor Amendment, Monroe called a cabinet meeting the very next day, March 3, 1820, to discuss the Missouri question. The cabinet agreed that Congress had the power to restrict slavery in the territories, but William Crawford, a southerner and the treasury secretary, contended that such territorial restrictions could not be binding on a state legislature. Secretary of State John Quincy Adams of Massachusetts, who later emerged as an abolitionist leader, thought Congress had the power to restrict slavery in new states but was nevertheless in favor of the compromise due to southern intransigence on the issue. Like Crawford, Monroe doubted whether Congress’s power to restrict slavery in the territories could apply to a sovereign state. Three days after this meeting, President Monroe signed the Missouri Bill, on March 6, 1820, which could perhaps be considered our true bicentennial.

The Missouri Crisis had endangered more than the threads of Union. It equally threatened the unity of the ruling political party, the Jeffersonian Republicans. At the time of the Missouri debates, this party had a virtual monopoly on the national government, as well as in nearly every state government, save some New England states. The War of 1812 and the Hartford Convention, primarily, had sounded the death knell of the Federalist Party. Following the 1816 presidential election, one-party politics, that is, Jeffersonian-Republican rule, characterized the American political landscape.

The Three-Fifths Clause

One of the recognized leaders of the restriction of slavery in Missouri, US Senator from New York Rufus King, declared that he did not care about slavery as a social system controlling blacks, and that he opposed the expansion of slavery because it affected the “great political interests” of white people only. The goal of many of the antislavery forces in Congress was solely to weaken the Three-Fifths Clause in the US Constitution, which for the purposes of Congressional representation counted “the whole number of free persons” and “three-fifths of all other persons,” meaning slaves, which increased the number of congressional representatives from the slave states, thus providing the South greater political power at the national level.

But Missouri caused a deep and nearly irreversible rift in the Jeffersonian-Republican ranks, pitting northern Republicans against their southern brethren. Many leading Republicans feared the Missouri issue was a Federalist ruse to regain political prominence, and charges of a Federalist conspiracy ran rampant through political circles.

Back in Missouri, the leaders of the territorial government moved rapidly. The popular indignation and outrage at Congress for delaying statehood spurred the people of the state to speedily complete the process. In May of 1820, citizens of the “state’s” fifteen counties elected forty-one delegates to Missouri’s first constitutional convention in St. Louis. The delegates represented some of the most recognized and influential individuals in the territory, and many of them would go on to serve in the new state government or in Congress.

The delegates were overwhelmingly opposed to slavery restriction in the state, considering New Yorkers Tallmadge and Taylor, as well as other leaders of the movement to halt slavery in Missouri, as outright enemies. A toast from a Fourth of July celebration in Marthasville indicated the widespread anger and animosity Missourians and their leaders felt for what they perceived as an anti-Missouri crusade: “Messrs. Tallmadge and Taylor—Politically insane—May the next Congress appoint them a dark room, a straight waistcoat, and a thin water gruel diet.”

Although few Missourians owned slaves, the vast majority of the delegates to the Missouri constitutional convention were southern born. Only three of the delegates came from northern states opposing slavery expansion, while two others were foreign born.

The very day the state constitution was adopted, July 19, 1820—could this be our legitimate bicentennial date?—the president of the convention issued writs of elections, under the authority of the “State of Missouri,” to the county sheriffs to commence elections to state offices. At the end of August 1820, Missourians had elected fifty-seven representatives and senators to the first General Assembly.

The first state legislature convened in September 18, 1820, at the Missouri Hotel in St. Louis. Later that afternoon, Missouri’s first governor, Alexander McNair, with our state’s first lieutenant governor, William Ashley, in attendance, delivered the first annual message. Ten days later, the General Assembly passed its first bill, which was immediately signed into law by the governor. Many more enactments followed, including moving the state capital to St. Charles, forming ten new counties, and electing our first three presidential electors to the electoral college for the presidential election of 1820. Our first state supreme court, composed of three justices, also sat for the first time.

But when our first elected US Representative, John Scott, and our first two appointed US Senators, Thomas Hart Benton and David Barton, arrived in the nation’s capital, Congress refused to seat them. While Missouri was creating and operating a legal and legitimate state government, our state constitution reached Congress and immediately renewed a firestorm of opposition.

Superior Orators

Although the content of the arguments for and against Missouri’s admission into the Union were evenly matched, one factor no congressman could deny: the South had superior orators. Northern congressmen opposed to slavery in Missouri all agreed on this advantage of the southern members. One northern congressman admitted that “the great speakers are almost all in the other side,” while another declared that the “southern people have a great preponderancy of talent against us.” Even Secretary of State John Quincy Adams, from Massachusetts, acknowledged the oratorical superiority of southern congressmen, complaining that the most eloquent speakers in Congress represented the “slavish side” of the Missouri dispute.

The state constitution contained a controversial clause, authorizing the state legislature “to prevent free Negroes and mulattoes from coming to and settling in the state upon any pretext whatsoever.” This effectively meant that under Missouri law, free black citizens in the North would be barred from immigrating to the state, an act which apparently violated Article IV, Section 2, of the US Constitution, which stated that “The Citizens of each State shall be entitled to all Privileges and Immunities of Citizens in the several States.”

Ironically, several free states, such as Illinois and Indiana, already had similar restrictions against the migration of free black people into their states. Still, the controversial clause of the Missouri Constitution incited another intense anti-

Missouri crusade in some northern political circles; this was their last chance to keep Missouri out of the Union.

Congress attempted another round of compromises, finally settling on one by Tennessee Senator John Eaton: “That nothing herein contained shall be so construed as to give the assent of Congress to any provision in the Constitution of Missouri, if any such there be, which contravenes [Article IV, Section 2].” The Eaton Proviso passed the US Senate on December 12, 1820, without a vote. They simply sent it to the House.

Henry Clay then again offered his exceptional skills in the House, pushing the Senate version, which had been defeated earlier. Clay formed a joint committee of House and Senate members, and on February 26, 1821, the Eaton Proviso passed by a vote of 87–81. The issue returned to Missouri for action.

Simply put, all Missouri had to do now was to enact legislation promising never to pass future legislation authorizing the offending section of the state constitution. Ironically, while Congress was denying Missouri statehood until such legislation was passed, it required of Missouri’s first General Assembly an action that belonged only to a sovereign state—passing state legislation. The state legislature cooperated, nonetheless, passing the Solemn Public Act in June of 1821.

President Monroe happily announced by proclamation that Missouri was now admitted, on August 10, 1821, our official bicentennial date. Despite Missouri’s solemn promise, our state repudiated the deal in 1825 and in 1847, passing legislation preventing free black people from immigrating to the state. Congress didn’t respond in those years, as by then, state sovereignty had prevailed.

Despite our controversial and divisive entrance into the Union—a struggle that overshadowed any other admission, Texas taking a distant second—we should not overlook our original bicentennial date this March. Why not commemorate all of these seminal dates of our statehood, every one of them from March 6, 2020, to August 10, 2021? We deserve the celebrations, for causing such a raucous entrance into the Union.

A New Word

The Missouri debates introduced a new commonly used word to the American language. During the extensive debates over Missouri, congressional speeches became so repetitive and boring that in February 1819, the House refused to hear the speech of Felix Walker, congressman from the Buncombe County district of North Carolina. Walker protested that his constituents demanded to hear him say something on Missouri and that he was determined to “make a speech for Buncombe.” From this emerged the word “bunkum” or “bunk,” meaning foolish talk or nonsense.

Photos // Library of Congress, North Wind Picture Archives, Wikimedia/Public Domain, Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division, Hunt’s Merchants Magazine and Commercial Review, Collection of the US House of Representatives, US Senate Historical Office, White House Historical Association

Related Posts

7 Missouri Waterfalls

A haven for gorgeous scenery, the Ozarks is brimming with stunning waterfalls. April and May are great months to enjoy our waterfalls, as water flow is at its peak from spring showers.

5 Campfire Recipes You Can Make All Summer Long

These recipes by Chef Liz Hu can be prepared ahead and cooked right in the coals of your campfire, or your backyard fire pit, in foil packets.