The Ozarks are not very impressive in photographs. That might seem ridiculous with Don Massey’s photos staring at you from these pages. But for the layperson with a camera, their beauty often fails to translate. From a fire tower, the Ozark hills look uneven in the way of crinkled bedsheets on a mattress. The intense green of its canopy presses out any sense of topography. They are decidedly non-mountainous, despite often being called mountains.

And yet, isolated backcountry still dominates. The 402 noncontiguous miles of the Ozark Trail run through those modest hills, perhaps one day to be regarded alongside more iconic trails as an American long-distance hiking gem. My partner Allison and I hiked its 210 contiguous miles from Thomasville to the Highway 21 Trailhead near Taum Sauk Mountain. The trail pushes through Mark Twain National Forest, the Ozark National Scenic Riverways, conservation areas, and a smidgen of private land where easements have been granted. The trail has been around in various stages of development since 1977, and it’s still at least two decades from being completed, if it ever gets there at all. Allison and I hiked from Thomasville to Taum Sauk Mountain in October, under hickories “glowing like candle flames,” as the conservationist Leonard Hall once wrote.

Like any good hike, The Ozark Trail is tough. The bedsheet description given above is an absolute lie. When you’re not in a fire tower, the Ozarks sink and rise like sine waves, from hill to hollow to hill to hollow. The OT can feel monotonous and tedious, a broad-scale meditation. In 210 miles, you get only two or three big views. But if one pays attention to the finer shades, the whole of the Ozarks’ history and present—both of its people and of the land—come into view.

MINING

A couple of days into our hike, we descended from the hills and forded the poorly named Hurricane Creek, a losing stream that dives underground into Missouri’s karst network. Light from the early evening sun speckled off the ripples of water curling around pebble shoals. The valley walls rose away in a darkening gradient, from the chartreuse of riparian sycamore, to the forest green of the hillside oak, to the dark pine greens on the ridgetop. It’s one of the most pristine places on the southern half of the trail.

It almost wasn’t. Eighty miles to the northeast, in the Old Lead Belt near Farmington, we’ve mined lead for 300 years. Still today, Missouri produces 70 percent of US lead. But by the 1950s, we’d exhausted lead mining near the Big River, and by the mid-’70s we’d finished Black River, leaving behind 250 million tons of contaminated mining waste. Hungry for lead and zinc, Doe Run Corporation looked to public lands, applying to do a little “exploratory drilling” in Mark Twain National Forest near Hurricane Creek. They drilled and found lead, but they never got to mine.

During the drilling, reports came out about lead contamination from chat piles up the Big River, whose floodplain had become one of the most heavily contaminated sites with heavy metals in the world. Bruce Babbitt, Secretary of the Interior, finally pressured Doe Run into giving up its permits in 1998. Which is good, because with the Ozarks’ three-dimensional karst aquifers, you can drop dye (or lead contaminant) into Hurricane Creek, watch it slip underground, and see it pump out of Big Spring 40 miles away. And who knows where else. Today the mining goes on in the National Forest near Viburnum, but at least not near Hurricane Creek.

CUTTING OF THE WOODS

On our fifth day, near the ridge that separates the Eleven Point and Current River watersheds, we met our first person. Marveling at what appeared to be a very close approximation to untouched presettlement savanna, Allison and I crunched through oak seedlings on a ridge and came out on a clearing, where a camouflaged man was creeping toward us, crossbow aimed.

The man lowered the bow, to our relief, and asked if we’d seen any deer. He was a bowhunter from Doniphan. Speaking with a soft cadence, he showed us a handgun he kept holstered, to protect from feral hogs. “They cut these woods” he said, pointing to the oak scrub we’d come out of. “Shameful.” The implied antecedent was the US Forest Service.

And indeed, the rest of the day was sunlit with discarded trunks and stumps. Since Mark Twain is a national forest and not a national park, the Forest Service can log away. Ozarkers’ respect for the woods and disdain for federalists is well documented in the novel and film Winter’s Bone, and though the film’s aesthetics were a bit extreme, its characters weren’t. Timber is sacred here. The OT winds through mature areas, timbered areas, and burn zones alike. It shows you what the Ozarks were and what they are, good or bad. Its hills are remote but never untouched. We passed three logging roads that day.

In the late 1800s, the northeastern states were cut and the South was in tatters. So from 1880-1920, we slashed the Ozarks to its bare skin, mostly for rail ties. What returns from the soil after a clear cut is an incredible diversity of grasses, blackberries, sumacs, and other pioneer species, then taller trees like sassafras, and finally oak and pine or oak and hickory. Without shade, the canopy trees photosynthesize sunlight in the way that kids inhale candy on the morning after Halloween, stretching high and fast with little regard to cell density. So they will be tall and attractive and even-aged and will snap or fall before old age. The second generation, the oaks growing in the shade of their mothers, have the potential to reach true old growth, if the Forest Service lets them. The process takes hundreds of years.

We are not there yet. The year 1920 was less than a century ago, and state forests didn’t really begin recovering in volume until the ’70s. The Ozarks, in their white and red oak, cedar, hickory, dogwood, shortleaf pine, sycamore, black walnut, papaw, and winged elm, despite their awesome beauty, are a recovering forest. Everything about it, every view and fact, is underlined by this point.

FLOODS

We came out of the woods a few miles from Van Buren at the end of our sixth day. The OT is a true backcountry trail that so far does not pass through any populated areas. We hitched a ride into town with Rob, who was from Doniphan, to pick up a resupply package in town. On the way, he detoured to show us Big Spring, which disgorges 286 million gallons of crystal azure water a day. On rainy days, it’s America’s biggest spring, cleaned by mineral dissolution underground. Its massive, swirling gush is as impressive as it is biodiverse. Thirty-eight animal species have been found only in Ozark springs and underground water, as well as the remains of Arctic musk ox, ground sloth, and mastodon.

The bridge near Big Spring was swamped in the historic April 2017 floods. If you don’t live in the Ozarks, however bad you think those spring floods were, they were worse. Every facet of life here was affected. Families and wildlife were displaced, property destroyed, research facilities flooded, banks eroded. The Ozark Trail itself was still highly damaged and overgrown in some areas, and one younger member of the Ozark Trail Association lost her first home. Some effects were even more insidious, like the aforementioned Big River lead pollution destabilizing.

Van Buren, which sits on the Current River, was wiped clean. Most of the businesses never came back. The Float Stream and the restaurant Rob’s daughter worked at—gone. Bank—gone. Church—gone. Outdoor supply store, crafts store—gone. “Some people had flood insurance,” Rob said. “I did. I got about half of everything back. Still waiting on the insurance for the other half. But other people, the ones that didn’t, they just don’t rebuild. Myself, I wonder if it’s worth it, the weather getting worse every year, if it’s just going to happen again. But at least the new house’ll be stronger.”

Before the roads, the rivers were the Ozark’s highways. Many of today’s major communities were set up along major Ozark river routes—Van Buren, Eminence, Doniphan—and those towns have been used to flooding ever since loggers would float a half a million rail ties downriver at once, creating massive logjams that would flood local properties. But thanks to climate change’s increased rainfall, the 2017 flood reached a stunning eight feet higher than the 1904 record. The Ozark Trail Association is making the best of it. In Pacific, the northern limit of the proposed backcountry portion of the trail, unwanted flood-prone property might soon bring the OT across the Meramec.

EMINENT DOMAIN AND SCENIC RIVERWAYS, GIGGING FOR SUCKERS

The Ozark National Scenic Riverways, the part of the Jacks Fork and Current River that is protected by the National Park Service, which carries 13 miles of the OT, was hit hard as well.

The park, headquartered in Van Buren, is a complicated park for Ozarkers like Rob. “There’s still a few families—I’m related to one of them, actually—who are still sore about them coming in when they were making the Scenic Riverways and telling people who owned millions of dollars of land here, who grew up on this land and whose fathers grew up on this land, that they had to get out for pennies on the dollar or get eminent domained.”

The controversy is 50 years old but well documented. The Ozarks were one of the first places eminent domain was ever used for purposes of “preservation” and “natural beauty.” That was frustrating to people who lived on the land and who were already profoundly aware of its natural beauty.

But plans had also been floated to dam the rivers, and Congress voted to preserve. In the late ’60s and early ’70s, judges and government officials forced hundreds of landowners off the river. Under-trained government appraisers sometimes valued properties at well under half their worth, and land acquisitions staff would, in some cases, frighten or intimidate elderly and unconnected landowners into selling at unfairly low prices. Judges, overwhelmed with the number of cases, pressured lawyers to waive jury rights for the trials. For their part, some lawyers made only halfhearted defenses. As historian Will Sarvis wrote in a journal article, “Apparently, the tremendous value that had inspired a Congressional act and a president’s signature was lost upon the government appraisers’ valuation calculations.”

After the trip I spoke with Dave Tobey, who grew up near Eminence during the condemnations and is now a National Park Service naturalist at Round Spring. To hear him tell it, the land was practically worthless on the market, and many landowners were more than happy to make an actual profit from the appraisers. In 1960, he himself had purchased 116 acres of riverfront land outside of town, just outside what became the park’s boundary. “Guess how we got that?” he asks. “We bought it on the courthouse steps for pennies. That’s land along the Jacks Fork River that sold for taxes. Even coveted land along the river went up for sale on the courthouse steps.”

But many Ozarkers still weren’t willing to settle. As John C. Colley testified to the House of Representatives in 1963, “We live in this particular area because we want to, not because we do not have busfare to leave.” In the end, the feds condemned the properties of 200 landowners who refused financial offers, moving them off by force.

Trust takes a while. I told Rob I’d worked briefly for the Missouri Department of Conservation, which he then blamed for the condemnations.

“Wouldn’t that have been the Park Service?” I asked. “It’s a National Park, isn’t it?”

“Well, yeah, I guess, probably,” he said. He shrugged. “But MDC, Park Service, you’re all the same to people down here.”

That broad suspicion of outside meddling has made a lot of landowners suspicious of easements or outright purchases by the Ozark Trail Council. Kathie Brennan of the volunteer Ozark Trail Association estimates that less than one percent of the current trail is composed of private land. Of what’s left to build, more than half of it is private. That’s why the OT isn’t finished. The problem is monumental, and the Ozark Trail Council seems unwilling to convince landowners to sign easements (though the OTA is starting to make headway). Instead, to reach the Arkansas state line, a distance of 52 miles, the OTA proposes to overlay 95 percent of that stretch on county and state roads, an unpalatable option, to put it mildly. “The Ozark Trail as it exists now was built on basically low-hanging fruit: public lands,” said OTA member Roger Allison. “That low-hanging fruit has been picked.”

Rob dropped us at a riverside campground that had been abandoned since the flood. We called the host, whose fading number was on a sign, who told us the mayor had rented the land and to call him. The mayor, fed up with high water, said he didn’t want anything to do with that spot anymore, and feel free to pitch a tent on it.

After twilight faded, a motorized johnboat with a deck of high wattage lights puttered upstream. As they neared, two men gripped sucker gigs, waiting like herons to stab the water for hog mollies. The Ozarks might have changed, but sucker gigging, one of the Ozarks’ oldest traditions, goes on. The deck lights, turned on to blind the bottom dwellers, silhouetted their weird pitchforks with their 10-foot poles and 2-inch prongs, and they made visible, even from the shoreline, the crystal clear bottom of the river. A hundred years ago, they would have used pine sap torches to light the water.

THE CURRENT RIVER

On our day off, we took a float down the Current. A spare, knotty Army vet shuttled us upstream and recounted how he’d recently beaten a neighbor who’d been hitting his own son. The mother was a drug addict, he said. The cops looked the other way, he said. In the Ozarks, there’s still space for vigilante justice, and where you don’t need it, you live and let live.

In many ways, the Ozarks are a closed place, which gives the region its noir aspect in film and literature. In fact, the five highest points in the Ozarks, located somewhere in Arkansas’s Boston Mountains, don’t have names. Yet seemingly every hollow does: Duncan, Reader, Deckard, Gusty, Brown, Graveyard, Pigpen, Becky, Threemile, Camp, Jenny, Betsy, Stillhouse, Spring, Deer Pond, Hog, Cowards, Bearpen, Mine, and Polecat Hollows decorate the Ozark Trail. Perhaps this just means there are several hilltops for each hollow. But to me it says that people here value the privacy of their lands, not the areas that rise into view.

As for the Current River, one can read all about Missouri’s natural communities in documents, but it is like imagining a new color, fascinating and believable, but impossible to really envision. Missouri nature writing is nothing but promises of beauty and lists of landscape types; the only language that articulates the beauty of Ozark rivers is that of the river wind itself. So I’ll leave it for you to investigate.

Upon the ridges, the oaks reached out above the riverside sycamores. Sixty-five miles upriver, well off the track of the OT, lay Welch Spring and the ruins of Dr. Charles Diehl’s early 1900s “hospital.” Diehl believed that the air from the adjacent cave healed consumption, and he established a glorified retreat for city folk suffering from consumption, asthma, and emphysema. In fact, as we know today, organic compounds produced by pine trees work as antimicrobial agents, scrubbing the forest air. If, a century ago, pines towered over along the ridges as they did throughout the Ozarks, Dr. Diehl might have nearly been right. But the healing days are past. Since the arrival of the timberman, Missouri has lost more than 90 percent of its shortleaf pine, replaced by the reaching oaks, and Welch Hospital is now just ruins and a black dot on a tourist map.

In a few places, the state’s native bamboo grew along the shoreline and harbored turtles, snakes, and bugs. Henry Rowe Schoolcraft, who walked the pioneer Ozarks in 1818, wrote about impassable fields of canebreak in the floodplains. Around that time settlers started using it as cattle feed until it disappeared, replaced by fenced-in hayfields. What he didn’t mention much were our celebrated gravel bars, which may have formed recently from eroded rock tumbling from deforested hillsides, replacing bankside canebreaks. River cane’s lush ecosystem is now a conscious conservation effort, an attempt to restore life and structural security to the riverbanks.

A VIEW OF TAUM SAUK

On the Current River section of the OT, we reached Mint Springs. With its rhyolite shut-ins, swimming holes, Blue Spring, elk restoration zone, and Stegall Mountain glade, this section is often considered the most beautiful.

The sun came in sprinkles through the red oaks, golden hickories, and pink dogwoods onto the open forest floor, where a stream trickled out of a foot-tall cave opening. Life—tiny black prosobranch snails, planaria, and water skaters—teemed in the spring. And larger life—Jo Swanson—appeared over the hill. “So I’m not the only one who hikes this trail,” she said, stopping to drink. Jo was a solo thru-hiker, an employee of the 310-mile Superior Hiking Trail in northern Minnesota, who has hiked nearly a dozen other eastern long-distance trails from Georgia to North Dakota. Comparatively, she said, the OT is more rugged in its backcountry nature and more solitary. It’s also rockier. If you’re not familiar with Missouri’s fist-sized, cherty dolomite, you might want to leave your ultra-light shoes at home and bring something with thick soles and ankle support. Trust me.

Later, atop Stegall Mountain, one of the OT’s highest climbs, we sidetracked to a fire tower, which we climbed and found a cycloramic view of the Ozarks. On the northeast horizon, three humble bumps rose over the surrounding hills, the only defining features of the endless rolling landscape. I gazed a long time before it struck me: one of those was Taum Sauk, 45 miles away, a winding 134 miles on foot.

CEDAR HISTORY: RANGE BURNING, RANGE CLOSING

The next few trail sections, Blair Creek, Karkaghne, and Middle Fork, are wide and manicured paths, thanks to a yearly 100-mile bike race that doubles as a fundraiser. The forest beside the trail varies greatly in age, from older trees along the idyllic Blair Creek to pine and cedar groves in Middle Fork and miles of dense, thickety oak scrub that’s impossible to penetrate or camp in—the result of a 2009 derecho that all but clear cut the region. We visited mystic Grasshopper Hollow, with its extremely un-catchy status as the largest nonglaciated fen complex in North America, and then resupplied at the Brushy Creek Lodge and Resort, which has turned a buck on OT hikers. After hiking along the idyllic Blair Creek, we came to Cedar Point, a narrow peninsula of raised land where we tried to camp inside a wall of cedars, whose young roots tell the story of a century of Ozark changes.

While the timbermen laid the hills low, St. Louisans came to terms with the state’s vanishing resources. But from the first, Ozarkers resisted regulation. In the late 1800s, when conservation hatched in Missouri, a full two-thirds of families in Missouri’s Courtois Hills were born in Tennessee, North Carolina, or Kentucky, where unmitigated hunting had been an embedded way of life for over 150 years. Now the government of a state they weren’t born in was regulating their land. And so government officials were told to expect armed resistance whenever approaching landowners.

And Ozarkers had a right to be suspicious. Conservation meant game laws. It meant no more burning of the understory. Conservation was also, in that Progressive era, a machine of capitalism, and the funders and leaders of state conservation were conspicuously large-scale timbermen, far removed from the small landowner.

Range burning was key to early life in the Ozarks. Fire scars on tree rings show that Ozark forests were burned regularly until 1810, the same year the Treaty of Fort Clark forced the tall and skilled Osage into Kansas. But as white timbermen moved in during the late 1800s, settlers who came with them reignited the practice, burning the woods to replace the brush with grasses. When the virgin timber supply coughed out and the lumbermen were left with no trade, they too ranged cattle. Over-grazing soon ripped out the nutritious grasses, and blackjack and sassafras brush replaced them. So naturally they burned those too, along with the soil’s humus layer, and the weeds grew back doubly fast. The clear-cut forest floor grew increasingly sprout-clogged, and land quality deteriorated.

There was also the fencing of the open range itself. Parceling off the range and thereby establishing property ownership benefitted rich industrialists. A St. Louis legislator pushed the policy, deepening the rift between the regulatory elite and rural Ozarkers. “In the rugged Missouri Ozarks, those who perceived the closing of the range as beneficial were of a decidedly different class and culture than the proponents of open range,” writes historian David Benac. “To benefit from enclosure, an individual had to possess the means and desire to acquire and improve land for pasture, cultivation, and participation in market agriculture. These were not the traits of Ozarkers in the most rugged portions of the hill country.” In other words, if you didn’t own land, you didn’t have anything to fence off, and when the open range was closed, there was nothing left for you.

Ozarkers held off significant reform until the 1930s and ’40s, but eventually the state won. The fires stopped and the range was closed. As a result, cedar sprouts grew unburned into cedar trees.

Ten years later, commercial farming began slowly revolutionizing life in the Ozarks, where subsistence farmers scraped by in the valleys. Increasingly large-scale farming equipment was too cumbersome for Ozark slopes, and big-time farming in Kansas, Illinois, and Iowa squeezed subsistence farmers into abandoning their plots. In Shannon County, for example, which the Ozark Trail traverses, two-thirds of its farms and nearly half its total farmland have disappeared since 1950. In the vacuum, sun-sucking cedar trees have rushed in. Beautiful as they are from a distance, Henry Rowe Schoolcraft barely mentioned red cedars on his march across the Ozarks in 1818. This past decade, they overtook white oak as the most populous tree in the state.

So I blame the closing of the range and the combine harvester for my nearly losing an eye several times trying to set up a tent among Cedar Point’s twiggy, low branches. Now, at Peck Ranch, at Stegall Mountain, and at other places along the OT, the Department of Conservation tries to clear them back. Where once the state banned burning, we now effectuate it.

ST. FRANCOIS MOUNTAINS

The fact of the Ozarks themselves raises some root questions. What are they? For geographers, it’s a three-plateau range in the country’s Interior Highlands, mostly in Missouri and Arkansas but also Oklahoma and Kansas, that has been spooned out by streams over millennia. For geologists, it’s something to do with karst limestone, dolomite, rhyolite, and epochal proper nouns. For ethnographers, it’s a hill country whose people carried Elizabethan dialect and Appalachian folk traditions westward, seeking that mythic American solitude. For college kids, it’s a float trip, and for New Yorkers, it’s a Netflix original.

But whatever the Ozarks are, they aren’t mountains—that is, until you get to the St. Francois Mountains, which came on the 17th day. These volcanic bulbs might not impress a Coloradan, but unlike the rest of the Ozarks, they are technically mountains. The scale of this part of Missouri, which contains Taum Sauk’s 1,772-foot plateau, is something different from the hills. Sure, these are still hills, but a different kind. It’s the Ozarks in a microscope, everything outsized and ancient. The hilltops across the valley through the trees look like spines of great dragons. They’re possibly the only land in the Midwest that has never swum the oceans.

Still, there’s some insecurity in the Ozarks being called mountains. The Ouachita, Boston, and St. Francois mountains are the only areas in the interior highlands that claim the name. Like any landform, the terms mountain and hill are nebulous. No height, slope, or volume graduates a hill to a mountain. Perhaps it’s that in the mountains one feels swallowed whole by nature, like an ant in a kingdom built for bigger things, and that hills are man-sized. One always thinks they can see over the top of them, even as they rise hundreds of feet overhead. In other words, in the mountains, the ego is crushed; in the hills, it is magnified.

Look at a relief map of North America. Between those two ranges, the Ozarks barely register.

But they do register. And they’re the only thing that does.

A SHIFTING LAND

The glades on Goggins Mountain are of another world. They are hot, scorched, naked, desertlike, with warped, twisted, and cracked oaks, and cedar groves, and collared lizards and cicadas and beetles and scorpions and tarantulas. Death is here in its alluring, American Southwest form. But also romantic life, with its soft grasses and wildflowers.

On the Bell Mountain climb, a copse of red maples was so thick under the sunny sky that suddenly, walking into them, the light on the mountainside turned pink. The Black River, high-fiving witch hazel on its way into Johnson’s Shut-Ins, swished toward Arkansas. Shagbark hickory, naked now, filled out entire hillsides for the first time.

Taum Sauk, as its brochures repeatedly warn, is underwhelming, but also the final landmark before the trailhead. It’s the sunlight-porous lobes of oak leaves that give the Ozark floor its dappled gleam, and through them we spent six miles trying to make out our car in the distance. Finally we did, and we left the woods.

The Ozarks, known as a place of viscous time, change like anywhere else. Populations are shifting to the cities, and migrant workers are flowing into the Tyson chicken factories. Forest trees are dying at an increasing rate, and yet young trees are growing even faster in their place. There’s no still life in the woods.

These hills, which have lain peaceably for 200 million years, which have birthed no powerful and brutal wars or civilizations, and which still appear as wilderness, as much as a Midwesterner can fathom it, are the perfect place to contemplate the wandering and vivid changes of geologic time. One can imagine schools of fish swimming a thousand feet over houses in West Plains, or Pennsylvanian peat swamps waterlogging Dent County, or primitive conifers looming in the Sunklands. Or you can look at photographs, at black and white cross sections of recent time, of men standing next to colossal, wrinkled pines that don’t exist anymore. But beyond that, there is no fixed definition of the ever-changing “Ozark,” into whose forests the white man walked 400 years ago and found already managed woods. The unassuming Ozark Trail, ever shifting through both social and natural storms, is the scribe for a shifting land.

The Once and Future Ozark Trail

The Ozark Trail turned 38 this year. In 1976, five years before construction began, a group of private Missouri landowners met to discuss the possibility of linking existing trails to create something bigger. A collaborative group called the Ozark Trail Council—a group comprised of the US Forest Service, the Missouri Department of Conservation, and other groups—formed to oversee the trail.

Eventually, the dream crystalized into a proposed 700-mile, trans-Ozark route that would combine with the Ozark Highlands Trail to connect the Arkansas River in Fort Smith, Arkansas, with the Mississippi River in St. Louis. The trail would establish Missouri’s and Arkansas’s Interior Highlands as the place of America’s next great long-distance trail. Construction shot off, with 200 miles of trail built in just over a decade. And then it stopped.

Once most of the public land corridors were taken advantage of, trail expansion became drastically more difficult, and the OT fell into disrepair. A trail champion emerged in 2002 in the form of John Roth, a retired businessman who formed the Ozark Trail Association and rallied volunteers to maintain the trail. Under Roth’s leadership, the OTA completed the Middle Fork section, which united two disjointed routes at last into a thru-hikable trail. Roth died in 2009.

Today, the volunteer Ozark Trail Association does all of the on-the-ground work, while the broader Ozark Trail Council meets annually but doesn’t effect much change. The work ahead includes a lot of convincing skeptical private property owners to let hikers pass through. “It would be extremely challenging for a group of volunteers to do it,” said Rebecca Landewe, an OTA member.

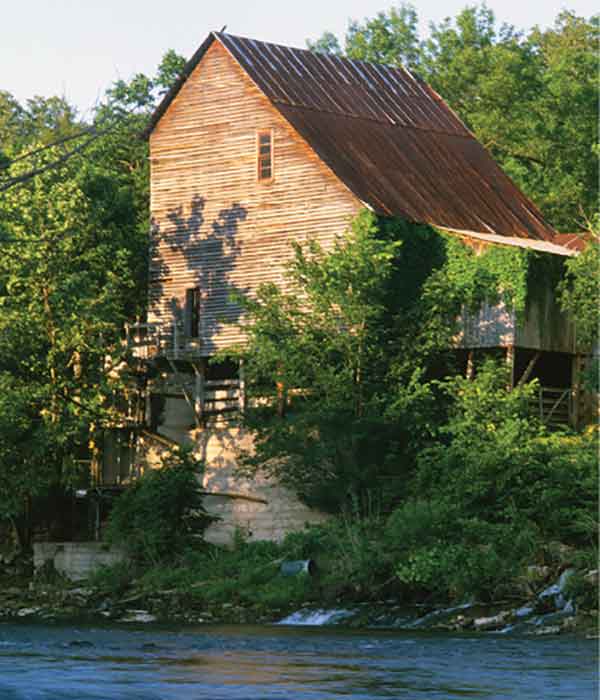

The trail, inching forward each year, has now broken the 500-mile mark, and has been named a National Recreational Trail. The stalwart OTA is crafting plans to reach Arkansas via Dawt Mill to the south and to connect with the Great Rivers Greenway near Pacific to the north, which would carry the trail all the way to Bee Tree County Park on the banks of the Mississippi.

The OTA always welcomes volunteers. For trail construction events, visit ozarktrail.com.

Journal of a Tour Into the Interior of Missouri and Arkansaw: excerpted

In 1818, three years before Missouri was granted statehood, Henry Rowe Schoolcraft and Levi Pettibone walked the Ozarks, starting in the mining town of Potosi. Schoolcraft published a written work both comic and beautiful, for which he is now sometimes known as the “Lewis and Clark of the Ozarks.” Here are some excerpts:

Nov. 6th, upon leaving Potosi – [W]e immediately commenced ascending a series of hills, which are the seat of the principal mines, winding along among pits, heaps of gravel, and spars … where scarcely enough ground has been left undisturbed for the safe passage of the traveller.

Nov. 8th, upon meeting a settler – She told us, also, that our guns were not well adapted to our journey … while we stood in astonishment to hear a woman direct us in matters which we had before thought the peculiar and exclusive province of men.

Dec. 18th, upon lodging with an remote family of settlers – Some days ago, a young child of Mrs. H being taken violently ill with what I considered a bilious attack, I administered one of “Lee’s pills,” which gave effectual relief, and the child suddenly recovered. This incident served to give them great confidence in my skill, and led to further applications. …. [I]n short, before I left their cabins, I dealt out all my pills, and acquired the reputation of being a great doctor.

Jan. 9th, on floating the White River – Every pebble, rock, fish, or floating body, either animate or inanimate, which occupies the bottom of [the river], is seen while passing over it with the most perfect accuracy; and our canoe often seemed as if suspended in air.

Jan. 30th – [The St Francois Range] is at once the most singular and interesting object in the geological character of the whole valley of the Mississippi … So considerable a body of primitive rock, in the midst of so unparalleled an extent of secondary strata, furnishes an interesting subject of inquiry, and its occurrence is certainly without a parallel in the scientific annals of our country.

Related Posts

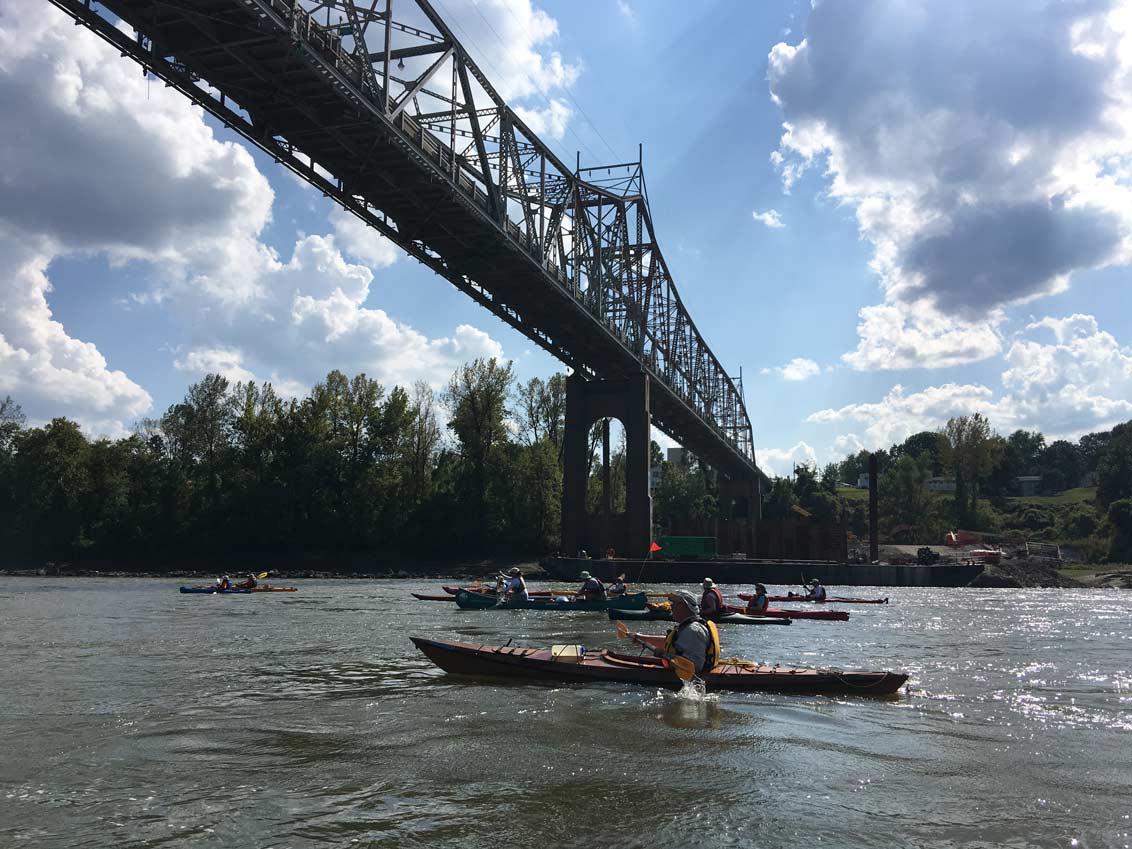

Paddle MO Offers 100 Miles of River History

You can traverse that history on Paddle MO, a five-day canoe and kayak journey on the Missouri River from Hermann to the confluence with the Mississippi River north of St. Louis.

Paddling 340 Miles on the Missouri River

From August 8 to 11, 450 crazy people will paddle down the Missouri River in canoes, in kayaks, and stand-up paddleboats—all competing against each other and themselves in the MR340 race.